boolProp testingcheats enabled true, or: The Critical Dollhouse

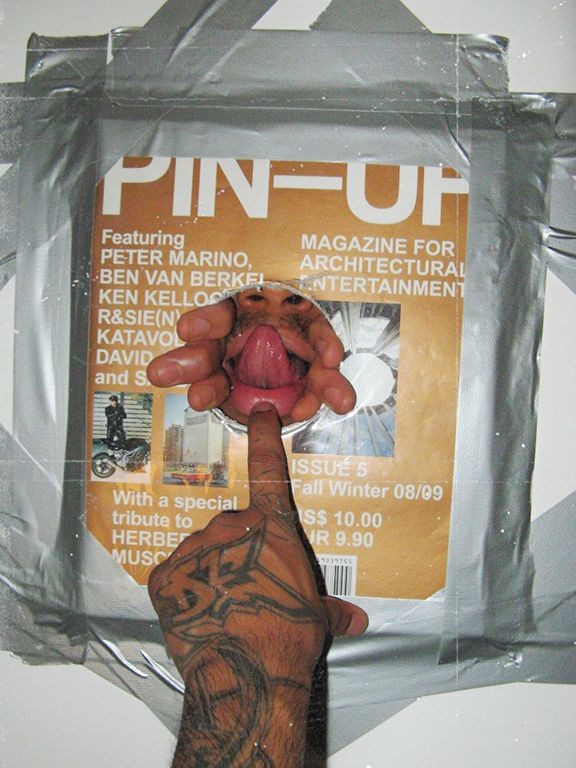

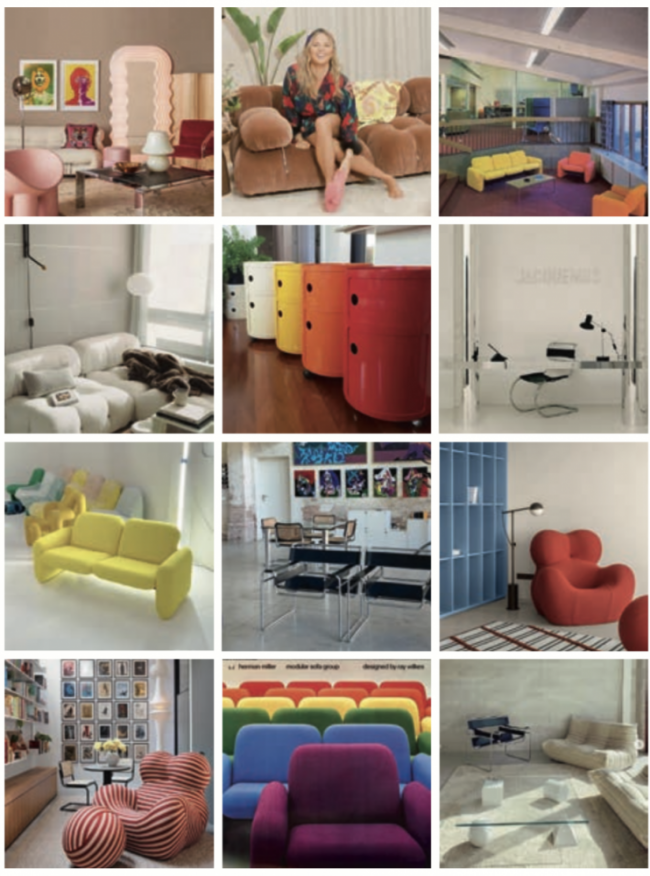

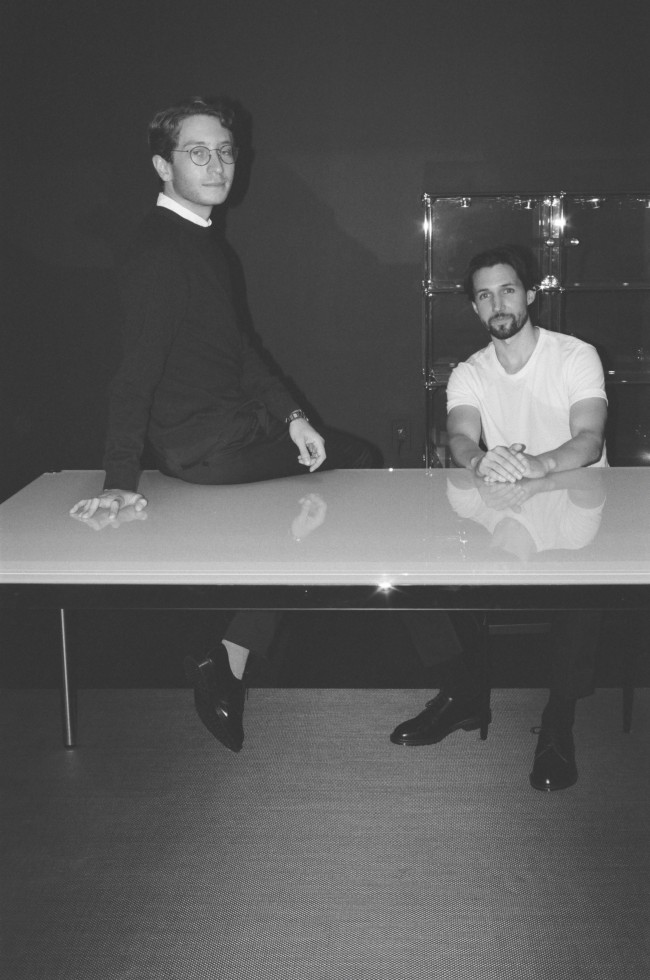

The exhibition Blow Up, curated by Felix Burrichter and designed by Charlap Hyman & Herrero, is an exploration on design, scale, and the conditioning of childhood. PIN–UP asked five authors to write a text around the theme of childhood, design, and their ideas of domesticity.

My primal scene: bed, morning, December 23rd, 1996. It’s my third birthday and I’ve been gifted my first Barbie. My mom regards me as I carefully acquaint myself with my new favorite toy, her face imbued with slight concern, but also, obvious satisfaction. I was ecstatic. Ballerina Barbie was unique because she was equipped with rotating and bendable limbs, making her easily assume even the most obscure poses; an intriguing ability that I promptly began exploring and mimicking with great enthusiasm in and outside the home. Forever clad in her hot pink tutu, Ballerina Barbie became a true loyal companion in the following years: she followed me to kindergarten, in the car, to bed, and to the public swimming pool, where her stiff, pointy ethylene-vinyl acetate fingers helped me turn on the showers in the male-only locker room. While my brother boasted an invisible male friend, I had Barbie. Through this inanimate object, I acquired the tools to navigate an, at times, difficult childhood environment, with its overwhelming masculinities and unspoken social norms. Through her, I first mastered the act of metaphor: to imagine myself as someone — something — else.

“If you scratch a child, you will find a queer, in the sense of, someone ‘gay’ or just plain strange,” writes Kathryn Bond Stockton in her book The Queer Child Stockton argues that gay children make us perceive the queer (odd, strange, un-normal) temporalities (such as repetition, fantasy, suspense) that haunt us all. “For no matter how you slice it, the child from the standpoint of “normal” adults is always queer;” she writes. Indeed, the child is pre- and poly-sexual, non-human, and post-human, non-gendered and schizo-gendered, there and not there, all at once. To these queer temporalities we might add queer spatialities: childhood is a landscape of idiosyncratic perversions, hazily played out, literally, as play, in a mix of virtual and real spaces that morph between each other in flux.

-

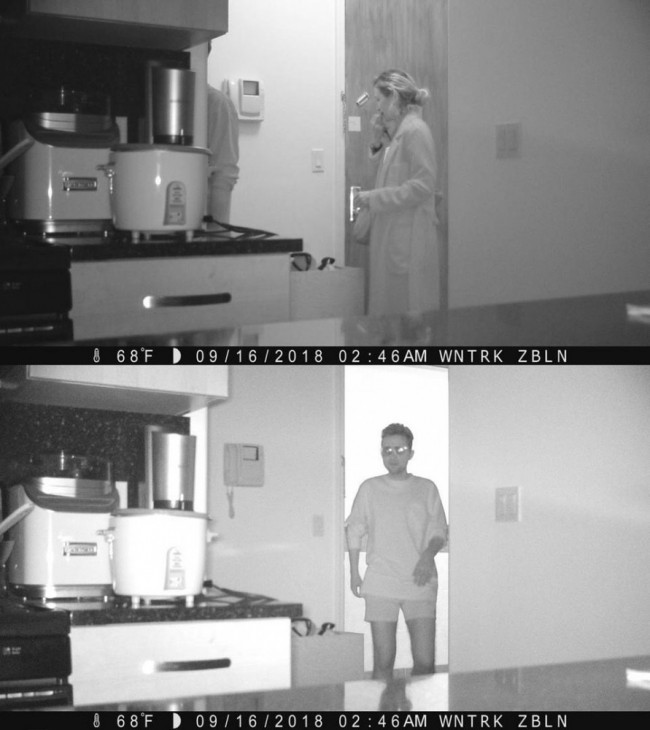

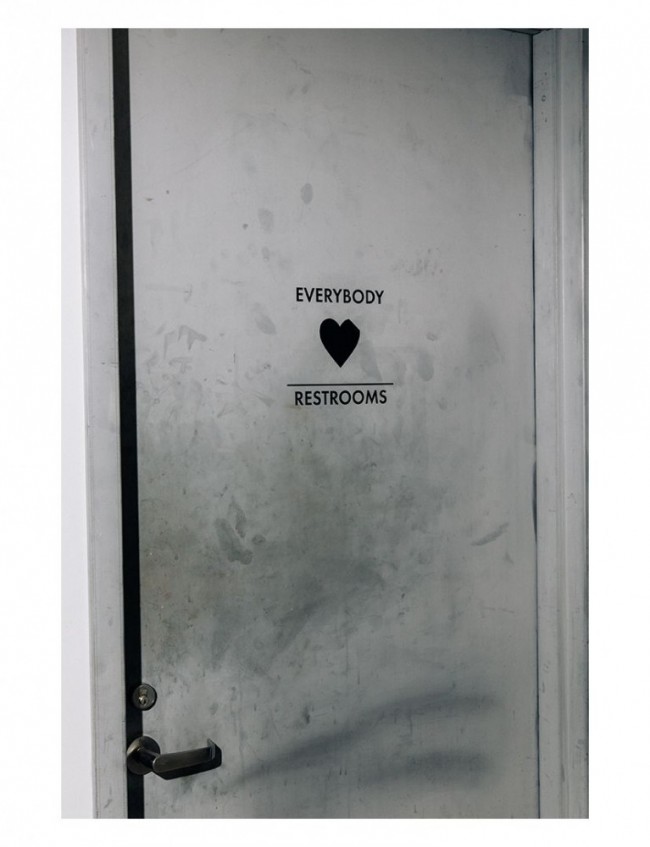

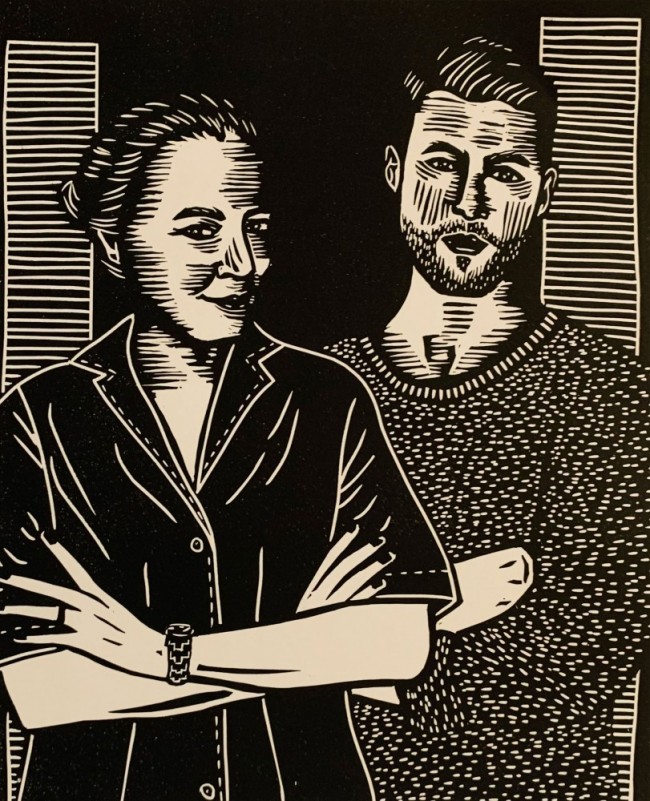

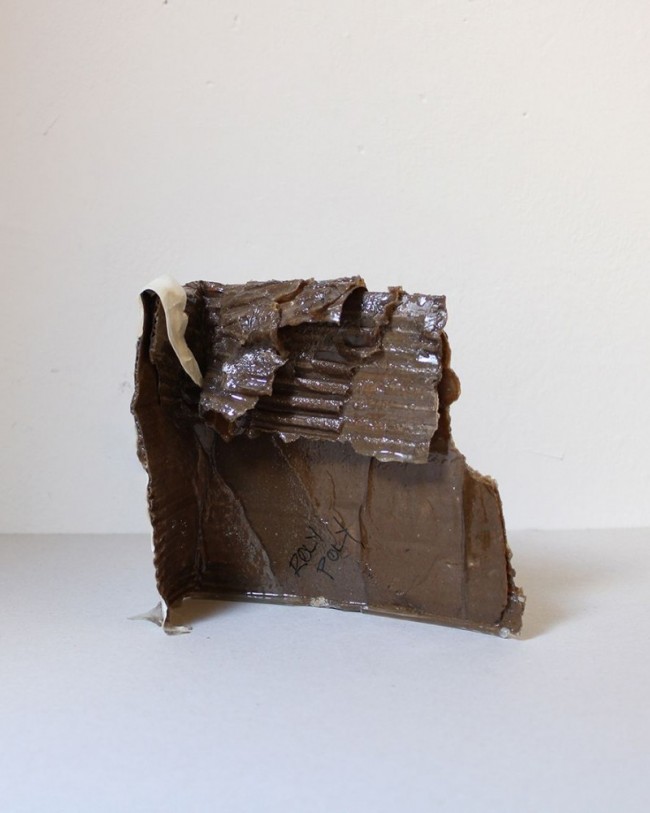

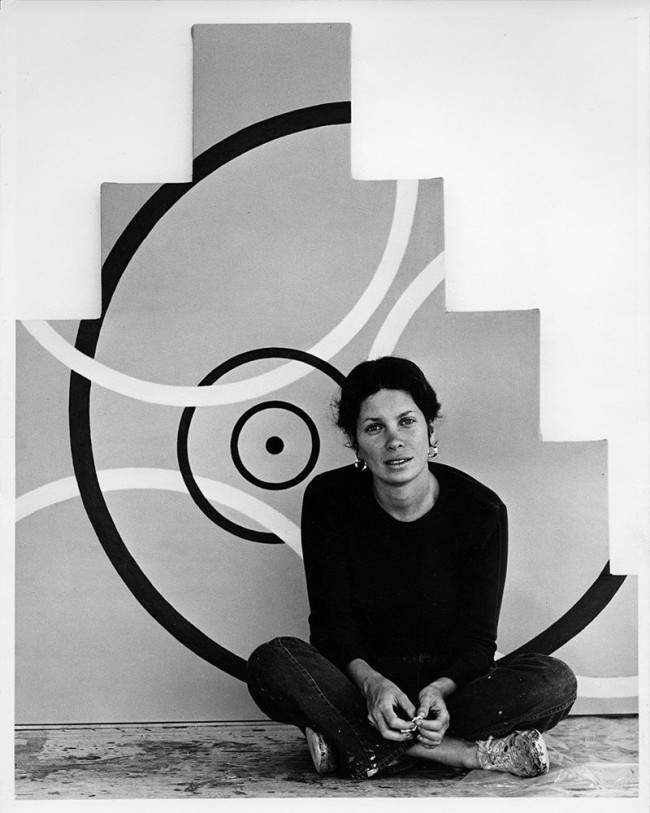

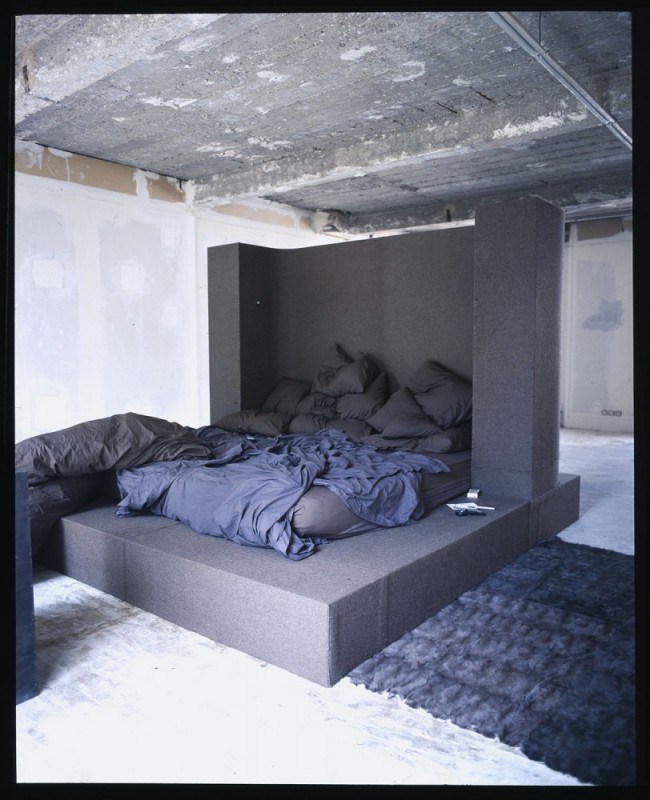

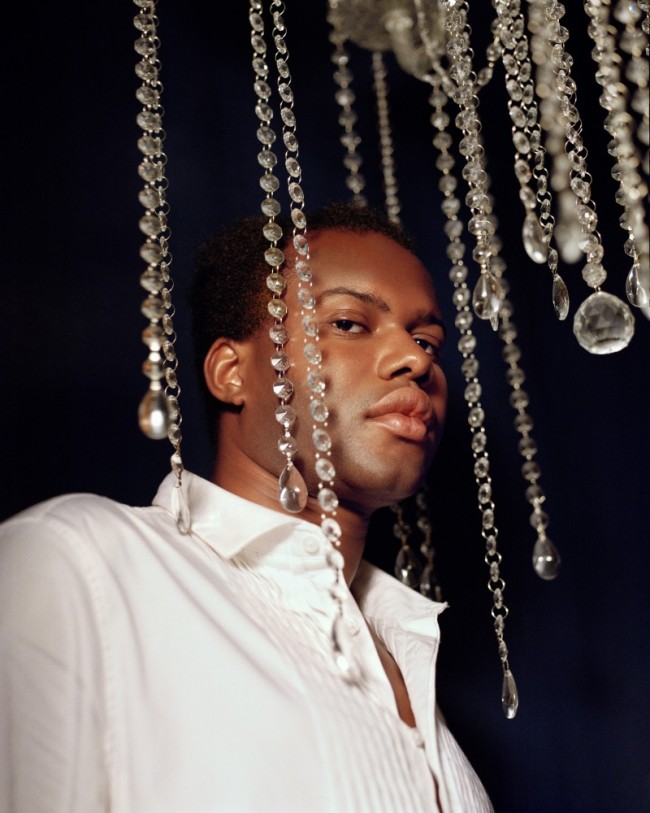

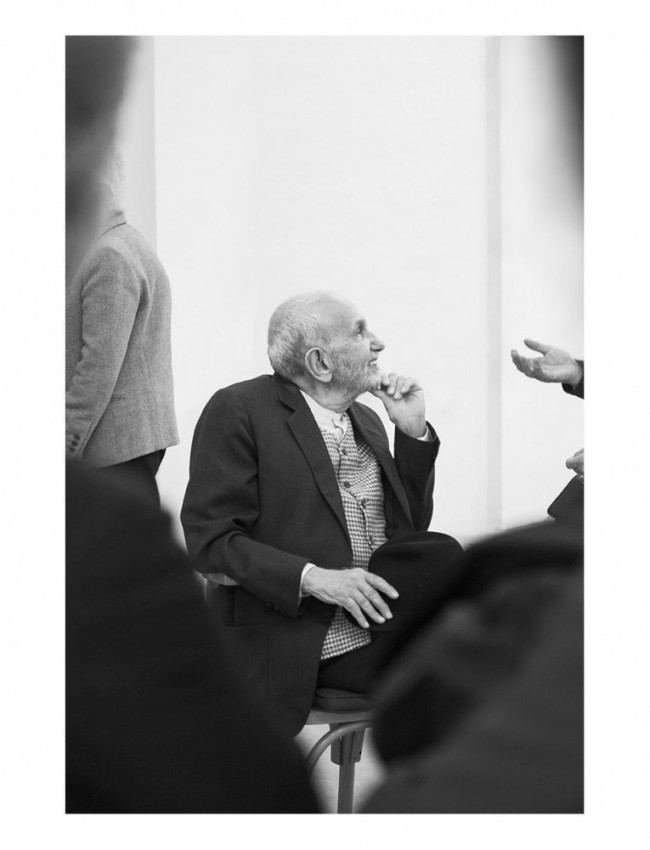

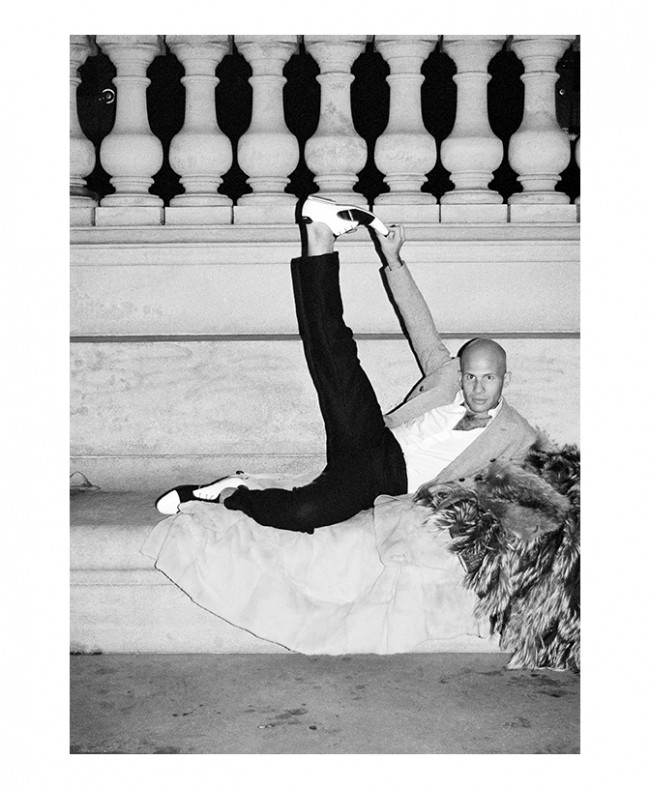

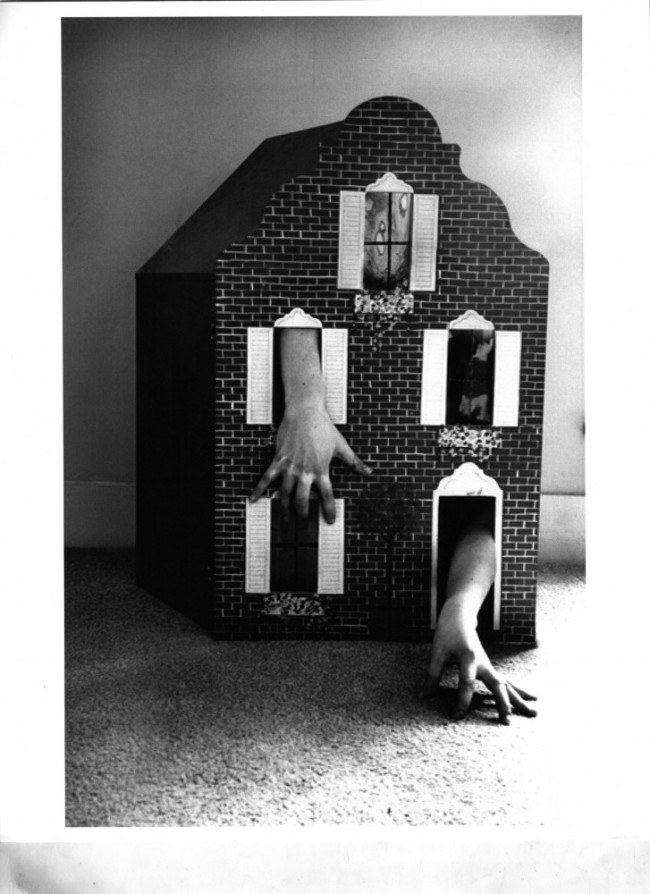

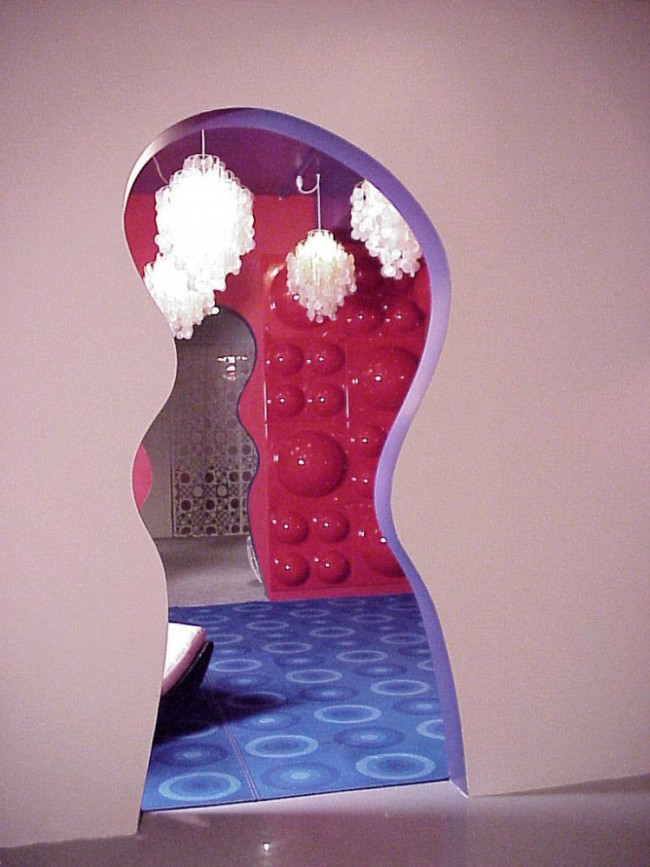

View of Blow Up exhibition. Photography by Timothy Doyon. Courtesy of Friedman Benda.

-

View of Blow Up exhibition. Photography by Timothy Doyon. Courtesy of Friedman Benda.

-

View of Blow Up exhibition. Photography by Timothy Doyon. Courtesy of Friedman Benda.

-

View of Blow Up exhibition. Photography by Timothy Doyon. Courtesy of Friedman Benda.

Since ancient times, dollhouses have been used to imagine and re-imagine domestic space along with children’s future roles within it — yet actual dollhouse-play for children was only popularized in 19th-century England (see Tobey Crockett’s “The Computer as a Dollhouse”). In her 1993 book Made to Play House, historian Miriam Formanek-Brunell explains that while adults in this time indeed found dolls useful for the social feminization of young girls — essentially preparing them for a life as domestic housewives — there is an equally traceable history of children “hacking” the household norms of the Victorian period through their own, critical forms of doll play. To this day, “playing house” — with or without dollhouses — is as much about disrupting the idea of a household as it is about enacting and reinforcing it, adding new, surprising characters (queers, royalty, terrorists, animals, monsters) or narrative plots (death, domination, magic, sex) that transgress the logic of domestic, heteronormative idyll.

The basic social and dramaturgical elements of dollhouse play — deciding the fate of human avatars interacting in a delineated social and architectural space — extend directly to the logic of modern-day video games known as “God Games,” where the player assumes the role of a Great Controller: an omnipresent onlooker in charge of autonomous characters which she guards and influences. The biggest of these games is, of course, the millennial game franchise The Sims. Like dollhouses, The Sims functioned as a virtual site where one negotiates domestic life, but adds a rather revolutionary architectural component that allows users to virtually plan and construct “dollhouses” of their own with relative simplicity. But while essentially functioning in the same way, The Sims is a much less gendered sphere of play than “brick-and-mortar” (plastic?) dollhouses, and thus a safe haven for young queers like myself, whose deep affection for Barbies proved increasingly problematic with age. By no means is The Sims any less queer than traditional doll-play, however: gay sex, torture, magic, and interaction with aliens were commonplace if not everyday practices in the bucolic suburban townships that Sims 1–4 allowed its users to build, customize, and control. Add to this well-known cheat codes, sourced from the social space of the early Web 2.0, which instantaneously suspend the faux American-suburban realism that the game — on the surface — obediently subscribes to. In Sims 2, motherlode famously provides an instant cash influx of 50,000 simoleons, while boolprop objectShadows, rather uncannily, removes shadows from all characters and buildings. My personal favorite was boolProp testingcheatsenabled true, a complicated chant I learned to spell out before even learning to speak English, and one that I still remember to this day: a kind of master code that allows for rather complex subversions of almost all of the game’s aesthetic and dramaturgical components. Through this code, I created permanently levitating mothers, CEO children, same-sex alien/human couples with offspring living permanently in a custom-built rose garden; I retired a toddler, forcing her directly to old age, resurrected a ghost, made her a master-chef, and had every inhabitant of my Sims village show up at a birthday party of five orphaned siblings who were all world-class chess players, only to drown everyone in their villa’s sizable pool by removing all the ladders.

-

View of Blow Up exhibition. Photography by Timothy Doyon. Courtesy of Friedman Benda.

-

View of Blow Up exhibition. Photography by Timothy Doyon. Courtesy of Friedman Benda.

-

View of Blow Up exhibition. Photography by Timothy Doyon. Courtesy of Friedman Benda.

-

View of Blow Up exhibition. Photography by Timothy Doyon. Courtesy of Friedman Benda.

In the idiosyncratic cosmologies of children, the very distinction between virtual and physical, between fantasy and reality, is highly malleable and up for negotiation. So do we, in these dollhouses, find the foundation for a queer strategy of subverting, resisting, or re-defining normative ways of being and inhabiting the world — and a strategy of re-writing cultural narratives of domestic space? Can we use critical doll-play to reverse and re-think traditional social roles, and help us broach life’s most powerful feelings — such as love, desire, and violence — in an experimental way? If so, how can we find ways to keep playing, to not grow up, but instead, “grow sideways,” as Stockton writes, and continue to generate new meanings, new fictions, new horizontal configurations of queer space, time, and sociality? “The child is precisely who we are not and, in fact, never were,” she reminds us, “It is the act of adults looking back.” But then, why did we ever stop playing?

Text by Jeppe Ugelvig.

Blow Up is on view at Friedman Benda gallery, New York until February 16, 2019.