BYZANTINE BLUES: TURKEY MEETS BELGIUM AT THE EUROPALIA ARTS FESTIVAL

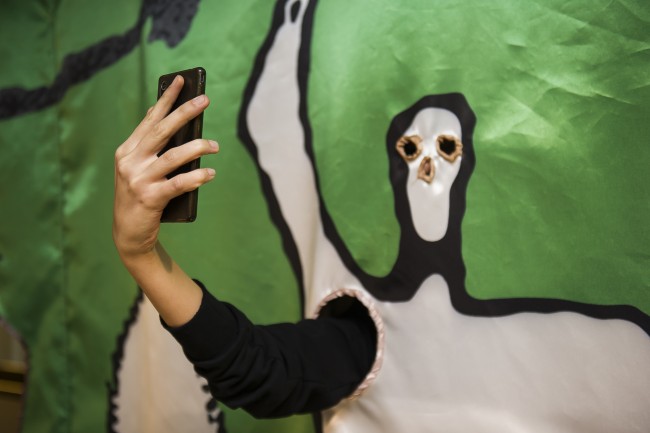

In 1969, the kingdom of Belgium launched the Europalia Arts Festival, a biennial at which a guest country is asked to co-program exhibitions and performances relating to its history and culture. Turkey was the 2015 invitee, and among the many events was the exhibition Istanbul – Antwerp. Port City Talks at Antwerp’s Museum aan de Stroom (MAS), which, as its title suggests, set out to portray and contrast the two waterside cities through a diverse selection of maps, objects, artifacts, and artworks. Given the context of the exercise, it was perhaps inevitable that Istanbul should come out the stronger of the two since, unlike Antwerp, the Sublime Porte was not present just outside the window, and so had to be conjured up by other means. Moreover the chief curator was Turkish, in the person of architect Murat Tabanlıoğlu, previously commissaire of Turkey’s 2014 Venice Biennale exhibit, and whose eponymous firm was responsible for the 55-story Istanbul Sapphire (2006–11), to date the country’s tallest building.)

As fans of Nobel-winning author Orhan Pamuk well know, Istanbul, the ancient capital of three defunct empires, can be a poignant place of nostalgia, melancholy, and regret. Ports in general can have that effect on visitors (rather like railway stations), but in Istanbul the weight of history, as well as the rapidly changing urban fabric, can induce in the flâneur a whole psychodrama of loss and yearning (not to mention the Stendhal syndrome). And it was this subtle sense of unease and wistfulness that the MAS exhibition captured so well, through a series of works by Turkish architects, photographers, and artists that were commissioned specially for the show. The tone was set in the very first room, where the curators had digitally recreated Sebah and Joaillier’s celebrated 1880s panorama of Istanbul (an original photographic print was also included in the exhibition) and superimposed today’s cityscape, shot from the same spot (the Galata Tower), over it in a slowly revolving wave, so that 100 years of urban change was accelerated into a relentless tsunami of redevelopment. Indeed time slowed down or speeded up — shrunk or stretched in Proustian fluctuation — was of the essence in this exhibition. Ömer Kanıpak, for instance, in his video Massive Ghosts, showed majestic close-cropped images of giant freight ships steaming up the Bosporus, but in slow motion, the better to prolong their fleeting, transitory presence and heighten the strange drama of what is, in fact, a very banal occurrence in such traffic-heavy waters. Refik Anadol’s Expected/Data Sculpture, meanwhile, visualized this frenetic to-and-fro in real time through multi-channel shipping data coming live from the Bosporus; Hasan Deniz’s (untitled) series of photographs of abandoned dock facilities, on the other hand, slowed time down to a standstill with its silent scenes of emptiness and decay.

Many of the works also demonstrated how a change in viewpoint can heighten awareness in new and strange ways. As a counterpart to the forced perspectives of Massive Ghosts, Emre Dörter and Elif Simge Fettahoğlu’s Planar Sections showed Istanbul as you’ve never seen it before, flat on, from above, as filmed by cameras mounted on drones. Following ships as they steamed through the endless blue, zooming in and out with astonishing alacrity, passing over bridges, quaysides, decks, and funnels, they captured images, saturated in the colors of summer, that were mesmerizingly beautiful. A strange perspective of a rather less literal nature was provided by Volkan Kızıltunç’s Gaps of Memory, which was composed of home movies shot in Istanbul between 1965 and 1985 on 8-millimeter and super-8 stock. The faded colors and flickering images ought to have had a distancing effect, but in fact showed scenes of ordinary people messing about in boats or enjoying themselves by the water that seemed startlingly contemporary and familiar, at least to these northern-European eyes. As the exhibition guide prudishly put it, “this project is based on the intersection between social history and individual memory… revealing a period which in official history remains obscure.” For the contrast between today’s aggressive, intolerant, Islamicizing Turkey, as envisioned by President Erdoğan, and the secular society captured in the films was startling. One sensed implicit criticism, but of course nothing was said out loud. Nonetheless, for a sputtering instant, those seemingly sunnier days were alive and glowing once again.