Drag Race, Sylvia Lavin, Herbert Muschamp, and the Architectural Realness of Rafael de Cárdenas

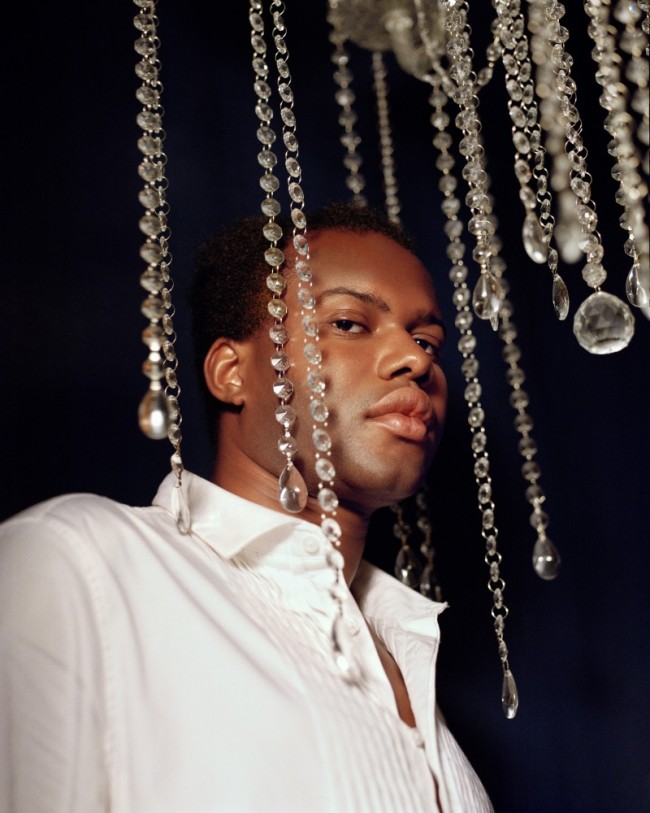

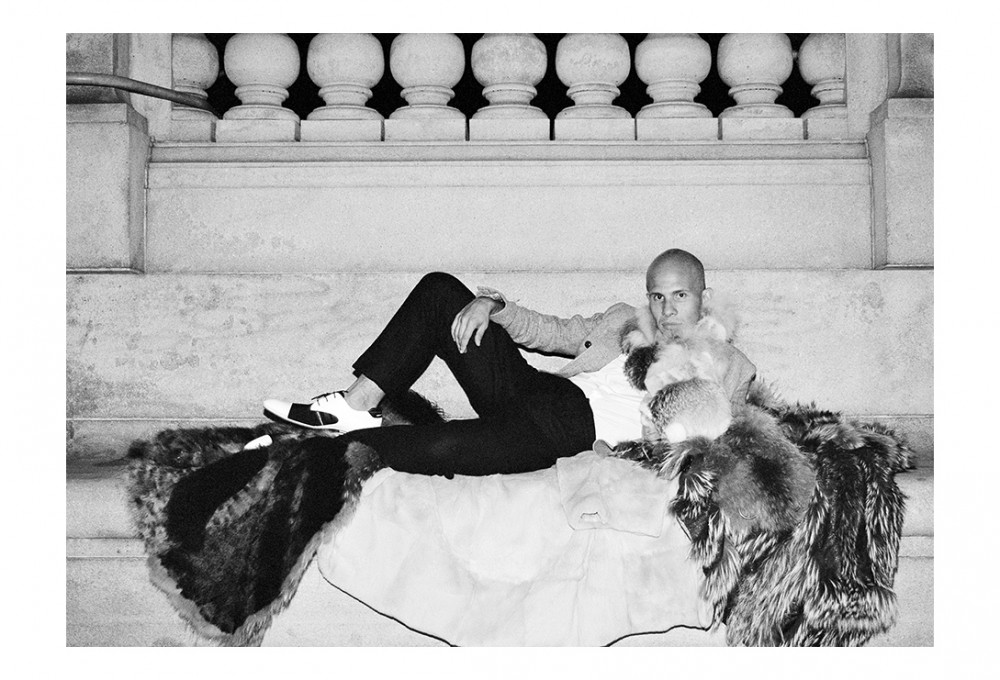

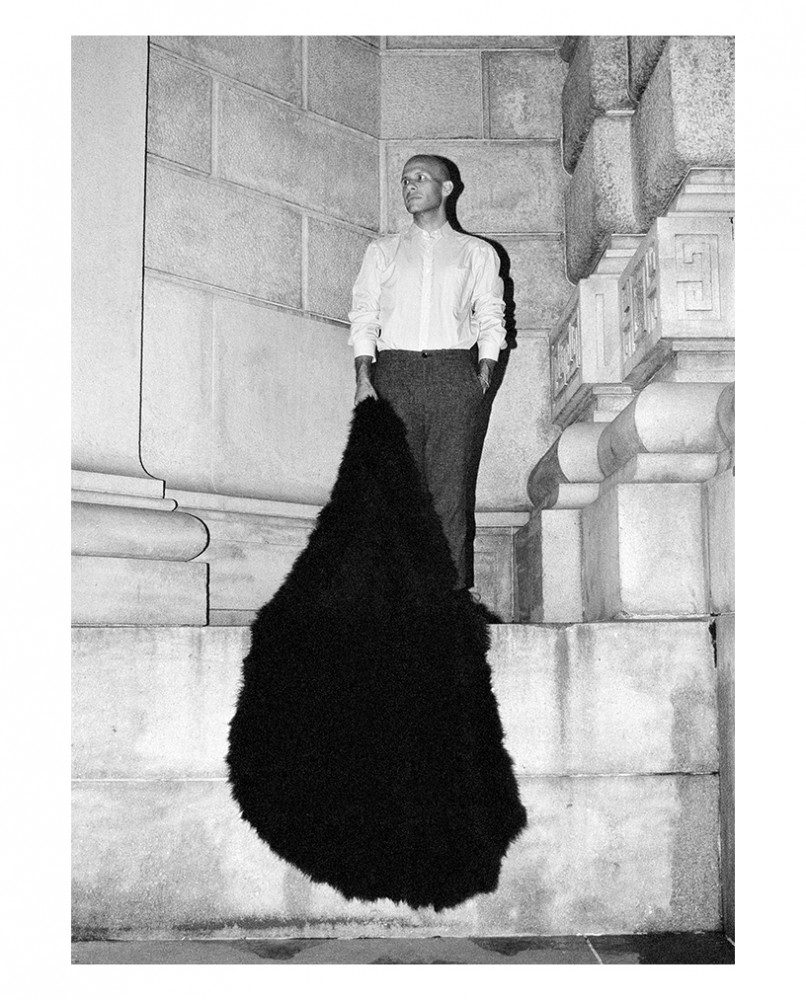

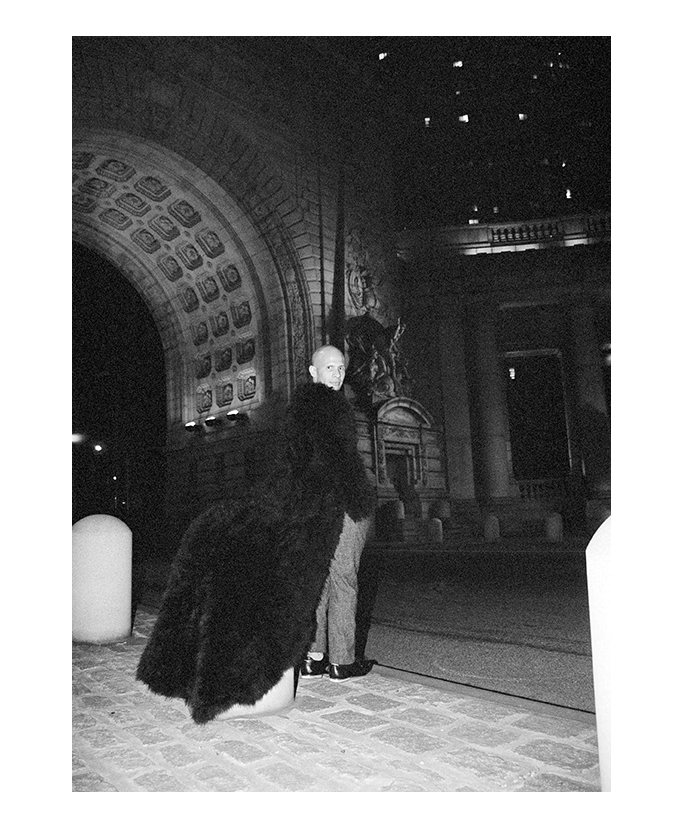

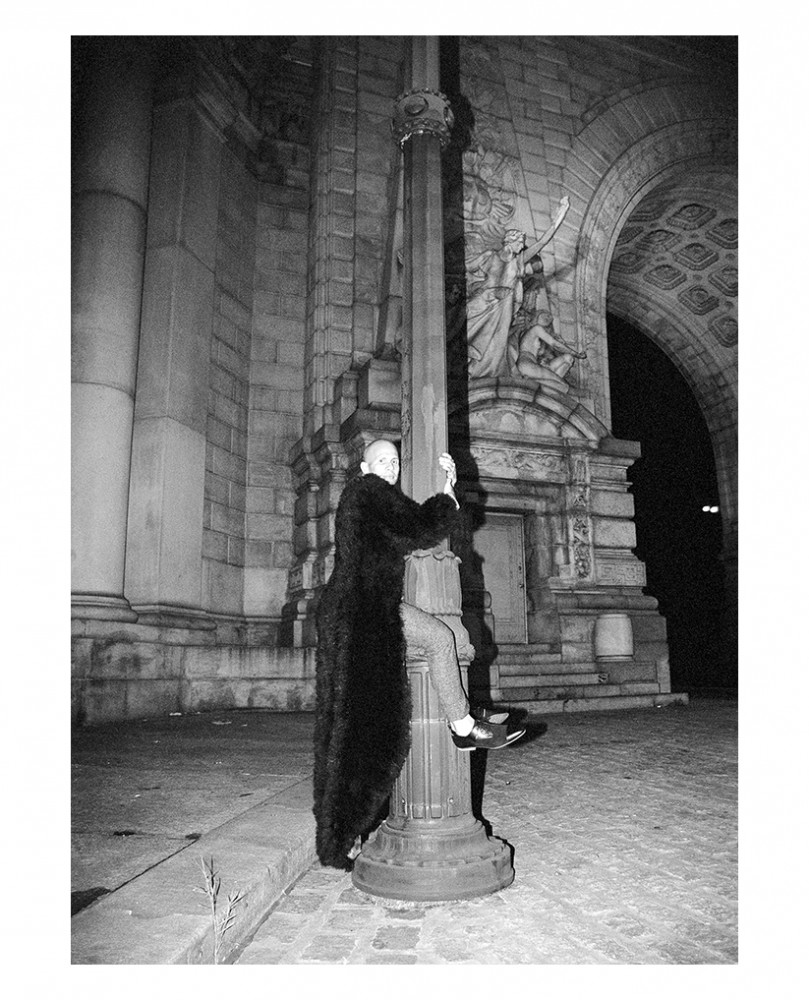

Rafael de Cárdenas, founder of Architecture At Large, photographed for PIN–UP 11 by Leonard Greco.

To understand the work of Rafael de Cárdenas and his firm Architecture At Large (RDC/AAL) is to understand the double wig. In season five of RuPaul’s Drag Race, the popular reality competition show that has been airing on Logo TV since 2009, contestants Alyssa Edwards and Roxxxy Andrews “lip-sync for their life,” which in the context of the show means staving off elimination. The contestants ready themselves to gyrate across the stage to Willow Smith’s 2010 hit single “Whip My Hair,” aiming to impress a jury of five presided by the show’s host, RuPaul. Halfway into her performance Roxxxy dramatically tears off her wig, only to reveal another wig underneath. The camera slows down and cuts to RuPaul’s face, mouth ajar in astonishment while co-judge Michelle Visage enthusiastically z-snaps in approval. The camera cuts back to Roxxxy lip-syncing and dancing at normal speed. Both contestants finish their performances but it’s evident to all what saved Roxxxy from elimination: her use of the double wig.

Drag performer Roxxxy Andrews’s famous “double wig” reveal during during RuPaul’s Drag Race Season 5, episode 7 (2013).

The success of the double wig, and the success of drag in general, rely on the seamless integration of layers and an ability to flawlessly synthesize diverse elements and genres into a cohesive whole beyond any soupçon of doubt. It is this layering that forms the basis of the practice of RDC/AAL and its unique ability to find, and combine, the right ingredients, the right references — the right wigs — for each project. It’s the transformation of doubt into power, and irreverence into perfection, creating a critical representation of present reality. The layers of de Cárdenas’ practice are as far-reaching as they are deep: influences from fashion, film, and popular culture; his Manhattan upbringing, including the New York nightlife of the early 90s; working for fashion designer Calvin Klein and architect Greg Lynn; his vast knowledge of art and architectural history filtered through the lens of his time as a graduate student at UCLA, where he studied with the architectural critic and historian Sylvia Lavin.

-

Manor House Pool Pavilion (2017), London, UK. Image courtesy RDC/AAL.

-

Manor House Pool Pavilion (2017), London, UK. Image courtesy RDC/AAL.

Once, when Lavin asked him to describe two projects, one by Steven Holl and the other by David Chipperfield, de Cárdenas used the word “elegant” to describe both. Lavin explained that the word meant so little, that it only means elegant, which is something that you know only when you see it. When he began fumbling for the right word, Lavin told him, “The words exist, you just need to sharpen your knives.” This sharpening is guided by a certain camp sensibility, not unlike what Susan Sontag describes in her canonical 1964 essay “Notes on ‘Camp’,” in which she argues “that one can be serious about the frivolous, and frivolous about the serious.” De Cárdenas’ method of working is similar, in that he is serious about seemingly frivolous influences, which he dissects, puts together, and makes his own — without ever taking himself too seriously. As a result, RDC/AAL may be a commercially successful firm whose projects attract high-profile clients and much media attention, but it really functions as a subliminal drag machine programmed by de Cárdenas, who injects layers from another time and zeitgeist into the present, creating unabashed Potemkin-style gesamtkunstwerks for shopping, dining, and living. In that sense, the spaces designed by RDC/AAL are environments that trigger emotions across time, and if you look at them through a drag-inflected lens, they show their layers, revealing moments and synthesizing atmospheres that belie their effortless execution.

-

Rafael de Cárdenas, founder of Architecture At Large, photographed for PIN–UP 11 by Leonard Greco.

-

Rafael de Cárdenas, founder of Architecture At Large, photographed for PIN–UP 11 by Leonard Greco.

-

Rafael de Cárdenas, founder of Architecture At Large, photographed for PIN–UP 11 by Leonard Greco.

The authority and seduction of RDC/AAL’s projects lie not only in the right combination of layers, but also in the “realness” of the atmospheric effects they achieve. This realness, this authenticity through artifice, is not the sort of thing you can close your eyes and imagine. Realness is more a visceral, visual sensation. Indeed, architecture can be a tedious discipline and a practice brimming with black-clad acolytes obsessed with technocratic functional considerations. It is rare that architecture takes its inspiration from any other areas of culture. Even among the contemporary practitioners held in high regard in professional and academic circles, the weight of history, jargon, of connection to some kind of correct past of “architectural” references seems de rigeur.

But not for de Cárdenas, who sidesteps the artificial good/bad dichotomy in favor of more affective terms. So-called “serious architecture” gets playfully mixed up with layers of pop culture, music, and fashion, only to be nonchalantly released back into “serious” architecture — transforming them from tedious to charming. In this regard, de Cárdenas had a kindred spirit in the late architecture critic Herbert Muschamp (1947–2007), who once famously compared Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Bilbao building to Marilyn Monroe’s dress blowing in the updraft air of a New York subway grating in The Seven Year Itch (1955).

-

The Montaigne Residence (2015), Paris, France. Image courtesy RDC/AAL.

-

The Montaigne Residence (2015), Paris, France. Image courtesy RDC/AAL.

-

The Montaigne Residence (2015), Paris, France. Image courtesy RDC/AAL.

De Cárdenas first met Muschamp when he gave a talk at UCLA. Years later de Cárdenas remembers that he was a frequent visitor to the New York office of United Architects, a super-group of architects composed of Greg Lynn FORM, UNStudio, Foreign Office Architects, Reiser + Umemoto, Kevin Kennon, Imaginary Forces, and others, who were participating in the 2002 competition for the new World Trade Center. During a discussion about The New York Times’ competition for a time capsule, Muschamp said that Santiago Calatrava’s submission, in elevation, looked like Mae West’s lips, but in profile it had a big sharp peak that would cut you if you actually tried to kiss it. He called it “a deadly kiss,” a reference de Cárdenas still loves and cites. But it’s important to qualify this sensibility, because despite his academic pedigree, de Cárdenas wants us to know that he is not an academic, despite this being the route he originally planned on taking; he thought it would grant him the freedom to do what he wanted to do. Indeed, he finds there is a disconnect between academia and practice, realizing the resistance in practice is part of what makes it so exciting.

Marilyn Monroe’s dress blowing in the updraft air of a New York subway grating in The Seven Year Itch (1955).

Scenes, costumes, and soundtracks from popular movies are an inherent part of almost any drag performance, and they are also a considerable part of de Cárdenas’s irreverent design approach. He doesn’t champion his own style, because style is easily exhausted. Instead, he tries to go beyond style by suggesting moods and effects. This goes beyond a specific interior, but rather permeates the larger construct of his work, like an atmospheric haze. For virtually every RDC/AAL project there are cinematic tropes or threads de Cárdenas extracts, but always obliquely, with a gleeful side-eye, and never the same for two projects.

-

Asia de Cuba (2015), New York, New York. Image courtesy RDC/AAL.

-

Asia de Cuba (2015), New York, New York. Image courtesy RDC/AAL.

-

Asia de Cuba (2015), New York, New York. Image courtesy RDC/AAL.

There is an iconic scene in 9½ Weeks (1986), one of the many films de Cárdenas likes to reference: Kim Basinger’s character Elizabeth is leaning back in a smoky haze in the basement of 101 Spring Street — in reality Donald Judd’s former home and studio in SoHo — advancing slides of artworks on a carousel projector. Her slow advance of the slides becomes faster and faster and eventually, she’s no longer concentrating on the academic tradition of rote visual memorization she went down to the basement to enact. Instead, she’s clearly thinking of John, played by Mickey Rourke, as she puts her high-heeled shoes on a classical relief and starts masturbating, all to Annie Lennox crooning “I guess it’s just a feeling.” This scene is like de Cárdenas’s thought process, where he unearths frivolous pleasures that arise from chronological layering and cultural juxtaposition. His seemingly endless personal almanac of film favorites includes cinematic hallmarks such as The Hunger, a dark and stylish 1983 cult classic with a vampire storyline featuring Catherine Deneuve, David Bowie, and Susan Sarandon, and a soundtrack by post-punk band Bauhaus; the musical Flashdance (also 1983), with music by Giorgio Moroder and elaborate dance sets inspired by the emerging era of the music video; Dune (1984), David Lynch’s visually dense science fiction epic; and the adult children’s movie Pee-wee’s Big Adventure (1985), an early Tim Burton vehicle with outlandish sets and witty spitfire dialogue.

-

NYC MAKERS: The MAD Biennial (2014), New York, New York. Image courtesy RDC/AAL.

-

NYC MAKERS: The MAD Biennial (2014), New York, New York. Image courtesy RDC/AAL.

-

Delfina Delettrez Boutique (2015), London, UK. Image courtesy RDC/AAL.

-

Delfina Delettrez Boutique (2015), London, UK. Image courtesy RDC/AAL.

Similarly important are a pair of documentary films from the late 80s and early 90s which influenced de Cárdenas in the same, almost unconscious, way in which one’s region of upbringing produces a linguistic accent, a sharpening of one’s voice: Paris is Burning, Jennie Livingston’s 1990 documentary about New York’s ballroom culture in the late ’80s, and Truth or Dare (1991), Madonna’s prescient reality-TV-style feature-length account of her 1990 Blond Ambition tour. Both films were cultural milestones for different reasons: Paris is Burning was one of the first films to shed an earnest light on an underground community, thereby offering a rare public forum for non-mainstream gender, trans, and queer voices and identities. Truth or Dare, while drawing from a similar pool of influences, took a mainstream approach, creating a hyper-stylized fauxcumentary of sorts around one larger-than-life pop personality and her diverse entourage. What both films share is the way their protagonists, in their very own distinct way, draw truth from the production of extreme artifice.

A scene with Junior LaBeija from the film Paris is Burning (1990) by Jennie Livingston.

The comedian Sandra Bernhard, who also has a cameo role in Truth or Dare, is another favorite of de Cárdenas, and her witty asides come forth in a style that is not unlike de Cárdenas’s own ability to drop biting rhetorical bombs. Bernhard’s film Without You I’m Nothing (1990) includes what one might think of as drag without the outfits: caricatures of old rich white women expressed through verbal description, as well as semi-unflattering celebrity impersonations. Her performance is like creating mental drag, relying on the viewer to complete the caricature — drag as an intellectual exercise. De Cárdenas has a similar approach to interiors but transcends the overly intellectual to actually give us the space, taking the leap of literally and physically embodying the descriptions that Bernhard intones in her film. Bernhard even skewers her former best friend Madonna, signaling that in order to entertain and seduce, nothing is off limits.

-

Greenwich Village Residence (2013), New York, New York. Image courtesy RDC/AAL.

-

Greenwich Village Residence (2013), New York, New York. Image courtesy RDC/AAL.

-

Greenwich Village Residence (2013), New York, New York. Image courtesy RDC/AAL.

Growing up in Manhattan meant that to de Cárdenas, these scenes were not a distant fantasy. They happened right under his nose, even if he didn’t always participate in person. He thought New York in the 80s and early 90s was the coolest place in the world, an opulent place of clubs like the Limelight and the Saint. He compares his practice to Madonna of that time, and posits that they both fundamentally work in similar ways: just as Madonna wasn’t a great musician or dancer, de Cárdenas doesn’t consider himself an amazing designer who necessarily loves interiors. He points to Blond Ambition, the singer’s tour that was the backdrop for Truth or Dare, which combined theatrical sets with costumes by French fashion designer Jean-Paul Gaultier, who produced one of pop’s most iconic flashpoints: the cone bra. According to de Cárdenas, that was the pinnacle of Madonna’s career where she had enough savvy to put together a few things and do something that hadn’t ever happened before: combine popular music with high fashion. It had nothing, or little, to do with the music, he maintains. In other words, it’s not so much what it is, but how it’s pulled off. De Cárdenas’ work is not about design, but about an ambiance, conjuring and capturing a mood.

-

Kushner’s (2011), New York, New York. Image courtesy RDC/AAL.

-

Charles Restaurant (2008) New York, New York. Image courtesy RDC/AAL.

-

Charles Restaurant (2008) New York, New York. Image courtesy RDC/AAL.

-

Demisch Danant Gallery (2016), New York, New York. Image courtesy RDC/AAL.

-

Demisch Danant Gallery (2016), New York, New York. Image courtesy RDC/AAL.

For all the opulence, the mood in the late 80s and early 90s in New York was profoundly marked by the AIDS crisis and by a full-blown economic recession. The era’s underlying hedonistic melancholy is something de Cárdenas deeply connects with. “Melancholy is kind of the only great mood, the only one that’s beautiful and sexy. All the others are just fun,” de Cárdenas says. “You could argue that melancholy is the moodiest of moods. It’s kind of a soft fog.” The relationship between opulence and melancholy reveals perhaps the most nuanced way in which RDC/AAL’s approach to architecture and design relates to the art of drag. Opulence, not as an adjective but as a state of being, is superficial, whereas melancholy is deep; it brings one down but also contains hints of pensive, brooding lugubriousness. It is easy to read ’80s opulence in RDC/AAL’s projects, but underneath another mood lingers. One might even say that opulence is a disguise for melancholy, a kind of melancholy in drag. The atmospheres in which melancholy is presented as opulence work by the same test of realness by which way, for example, a man subverts the tropes of female dress to break the gender binary and pass as another, realer version of himself — like a lie that performs the truth. The realness of this performance is the fulcrum on which this delicate act depends. It’s the litmus test of successful drag — of artifice as content, of surface as depth. In de Cárdenas’s case too, his capacity to defy expectations of what architecture is supposed to be does not come at the expense of content — it is due to an abundance of it. And however many layers of “non-architectural” artifice they may contain, there is no doubt that his work is “real.” The fact that de Cárdenas openly acknowledges and even relishes in the ambiguity of his practice is what makes his approach unique. And it is the flawless convincingness of these projects as architecture, and the flawless nonchalance of their delivery, where lies the architectural realness of RDC/AAL. In the words of drag queen legend Dorian Corey from Paris is Burning: “To be able to blend, that’s what realness is.”

Text by Jesse Seegers.

An earlier version of this essay was published in Rafael de Cárdneas/Architecture at Large: RDC/AAL, published by Rizzoli (2017).

All portraits of Rafael de Cárdenas by Leonard Greco for PIN–UP 11, Fall Winter 2011/12. Styling by Khalid Al Gharaballi.