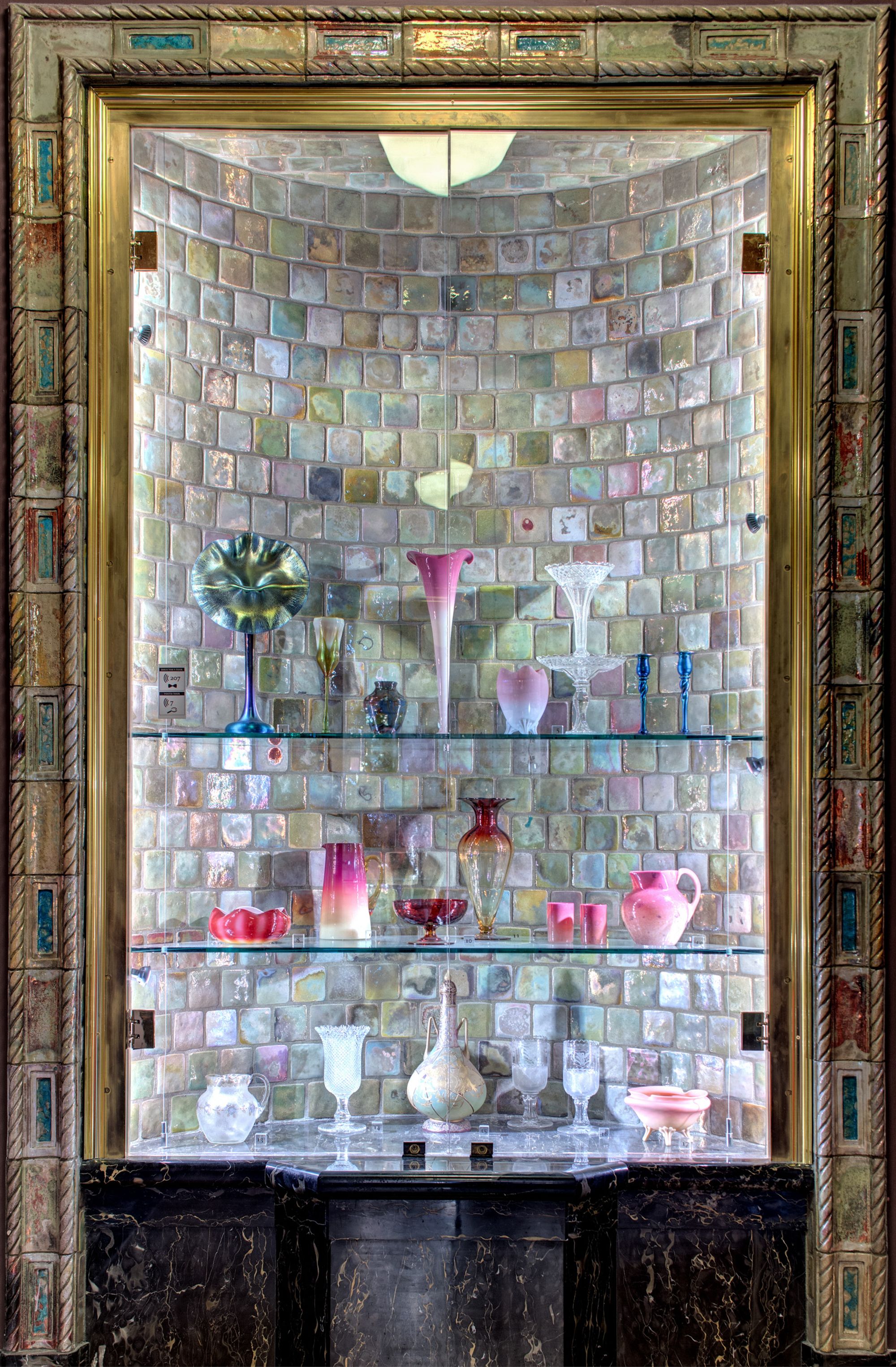

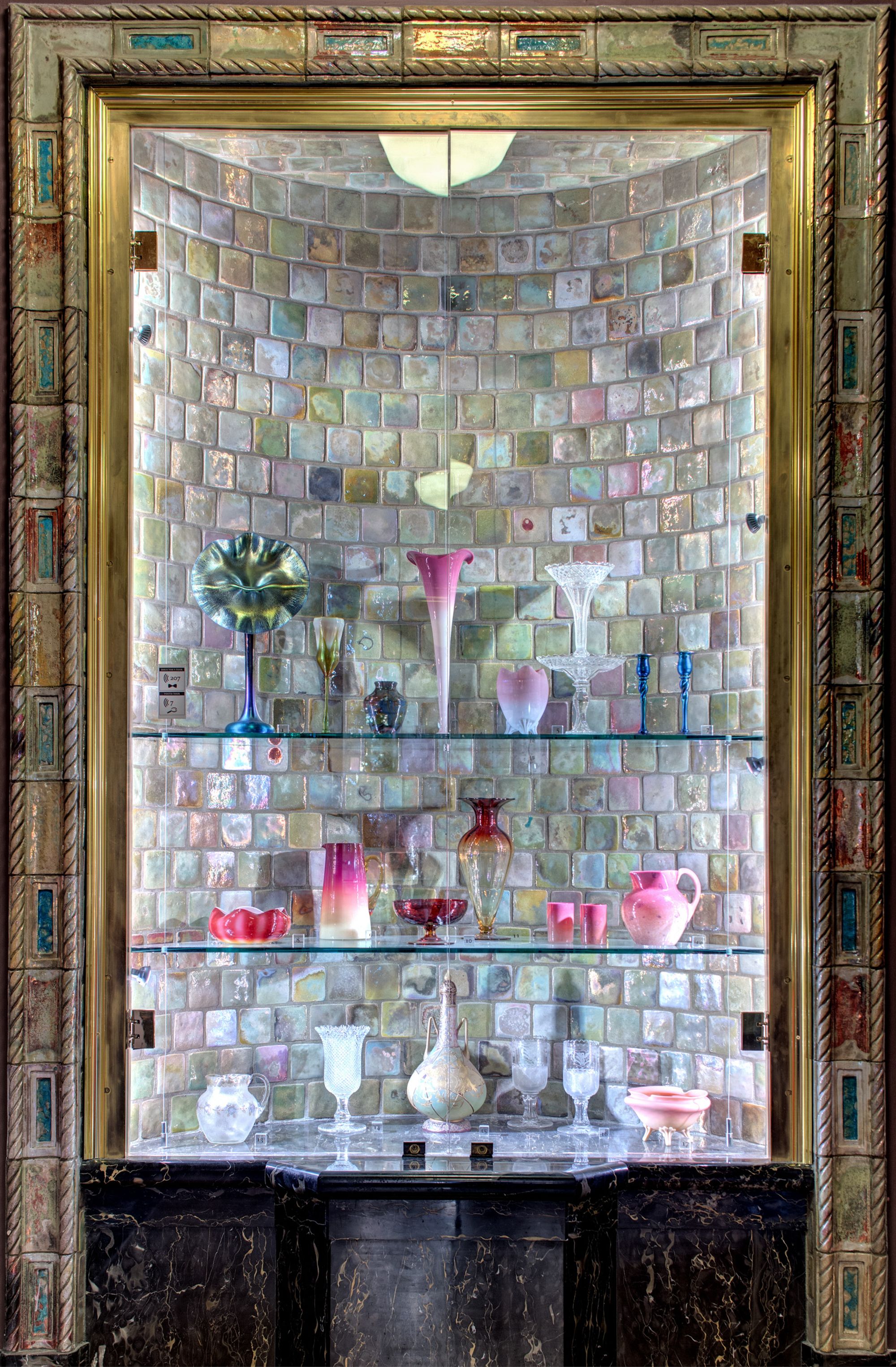

Pewabic tile installations at the Detroit Institute of Arts. Photo by Jason Keen. Courtesy of Pewabic Pottery.

The exterior of the Dabls MBAD African Bead Museum in Detroit. Courtesy of Kresge Arts in Detroit.

In Detroit, gallerists, designers, artists, students, curators, developers, even baristas, speak with a unique note of pride about their hometown, the kind that teeters between optimism and sales pitch. After overcoming seemingly impossible economic odds — the 2008 collapse of the auto industry that nearly took the city down with it — Detroit stands as a glimmering example of how a place can get back on track, though not without contradiction.

It’s been ten years since Detroit defied expectations by becoming the first, and still the only, U.S. metropolis to receive UNESCO City of Design status. The designation, conferred by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, honors cities where design not only functions as an essential civic practice, but a catalyst for social progress. Only 40 cities worldwide, including Cape Town, South Africa, Bangkok, Thailand, and Istanbul, Turkey, hold the title, chosen for their design economies, built landscapes, and living networks of schools, studios, and thinkers who treat design as a shared essential language.

In 2015, the year Detroit received its UNESCO title, the city was still reeling from overlapping crises that had left entire neighborhoods hollowed out. Downtown felt like a post-apocalyptic animation: baroque skyscrapers abandoned, windows shattered, industrial-age grandeur fading away. UNESCO status didn’t erase these realities overnight, but it did galvanize investment, international attention, and the belief that Detroit’s creative inheritance could also be its antidote. The prestigious title recognized not only the city’s legacy as the birthplace of the automobile and midcentury Modernism, reflected in its remarkable early 20th architecture, but also the enduring vitality of its creative community.

By then, the “artists-as-pioneers” gentrification narrative had already hardened into cliché, a familiar, sometimes cynical strategy developers employed to convert imagination into equity. But in Detroit, the exceptionally low cost of space made real experimentation possible, from the shared studios of Ponyride and the affordable live-work lofts of Artspace to the tuition-free animation training at Gunner School, and the innovative residential projects and restaurants developed by Prince Concepts (including The Caterpillar, an eight-unit arched metal bunker, and popular new destinations like KATOI and BARDA). LANTERN, OMA’s adaptive-reuse complex, extends that spirit, housing the Progressive Art Studio Collective for artists with developmental disabilities and Signal Return, a nonprofit letterpress and printmaking workshop. A handful of young design galleries have also emerged, fostering local, often Cranbrook-educated talent, including I.M. Weiss Gallery and Matéria. The artists represented by these galleries have stayed in Detroit, sustained by the affordability of space that let them commit entirely to their practice, something that’s become nearly impossible in other cities in the U.S.

Today, downtown Detroit feels like a movie-set version of itself: façades restored, lobbies lively with activity. Developers, rushing in for better or worse, have revived much of the historic core of the city, bringing New York City prices with them. I stayed at the Siren Hotel, a lavish restoration of the 1926 Wurlitzer Building developed by ASH NYC in collaboration with Quinn Evans Architects. Together, the duo restored the building beyond its original splendor. In the campy, opulent, all-pink Candy Bar downstairs, an Old Fashioned costs 18 dollars. The drink perfectly captures the paradox of Detroit’s resurrection: a luxury revival priced beyond the reach of many of the locals who never gave up on their hometown.

Invited by Design Core Detroit, a nonprofit dedicated to fostering a vibrant design economy, I spent three days in Motown taking in the city’s ongoing creative resurgence. Dozens of sites made an impression, but these few distilled what felt essential about the city’s design spirit: a sense of reinvention rooted in the past yet tuned to the future.

Exterior view of the front of Pewabic Pottery. Photo by E.E. Berger. Courtesy of Pewabic Pottery.

At Pewabic Pottery, a museum, store, and production facility, there’s a sign quoting the American Ceramic Society’s 1927 prediction that the studio “would live to be enjoyed long after the automobile had passed into the limbo of useless contrivances.” The prophecy hasn’t quite come true, but its confidence in Pewabic’s longevity proved prophetic.

Founded in 1903, Pewabic is among the country’s oldest continuously operating ceramic studios. Its 1907 Tudor Revival home — modeled after an English inn — on Detroit’s east side remains both a National Historic Landmark and a working studio, filled with the low hum of kilns, the scent of wet clay, and the shimmer of glazes drying on long wooden tables.

The company emerged from a partnership that seemed improbable: Mary Chase Perry Stratton, a Detroit artist raised in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, had trained in porcelain painting and clay modeling, and Horace Caulkins, a Canadian-born dentist turned entrepreneur, had invented a small, high-heat furnace for firing porcelain teeth. When Mary discovered his kiln at a local studio, she recognized its creative potential. Mary introduced the kiln to other artists, refining a tool made for dentistry into an engine for art.

Group of vases in a rainbow of glazes from Pewabic Pottery. Photo by E.E. Berger. Courtesy of Pewabic Pottery.

Pewabic tile installations at the Detroit Institute of Arts. Photo by Jason Keen. Courtesy of Pewabic Pottery.

Sacred Heart Major Seminary in Detroit featuring the second-largest Pewabic tile installation to date. Photo by Jim Haefner. Courtesy of Pewabic Pottery.

By 1901 they had opened their first studio in the carriage house of the Ransom Gillis House in Brush Park, naming their enterprise Pewabic after a copper mine near Mary’s hometown. They developed the iridescent glazes that made Pewabic famous, which caught and refracted light like oil on water. Pewabic tiles spread across the city and beyond, to schools, churches, and train stations, and as far as the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C., each one a convincing argument for the vitality of ornament.

Now operating as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, Pewabic continues its founding mission “to enrich the human spirit through clay.” In the gift shop, I buy my partner’s mother, a long-time Michigander, a small green ornament impressed with the outline of the state, encircled by the phrase “Michigan: Enjoy the Beauty and the Bounty.” It’s a modest object imbued with the conviction of an organization that still believes art can make ordinary life more beautiful.

The Pewabic Pottery fireplace in Saarinen House at Cranbrook. Photo by Amanda Rogers. Courtesy of Pewabic Pottery.

The Guardian Building in Detroit featuring large-scale Pewabic tile installations. Photo by Amanda Rogers. Courtesy of Pewabic Pottery.

The exterior of The Shepherd. Photo Jason Keen. Courtesy of Library Street Collective.

Like Amant or CARA in New York City, Detroit’s answer to the new wave of privately funded art nonprofits is The Shepherd. From the street, the early 20th century red-brick church, originally Good Shepherd Catholic Church, looks almost unchanged: arched doors and windows, a softened Romanesque-Revival façade. Only a new sculptural metal arch surrounding the main entrance hints at the sensitive renovation within. At first glance, it’s easy to mistake the building for the house of worship it once was.

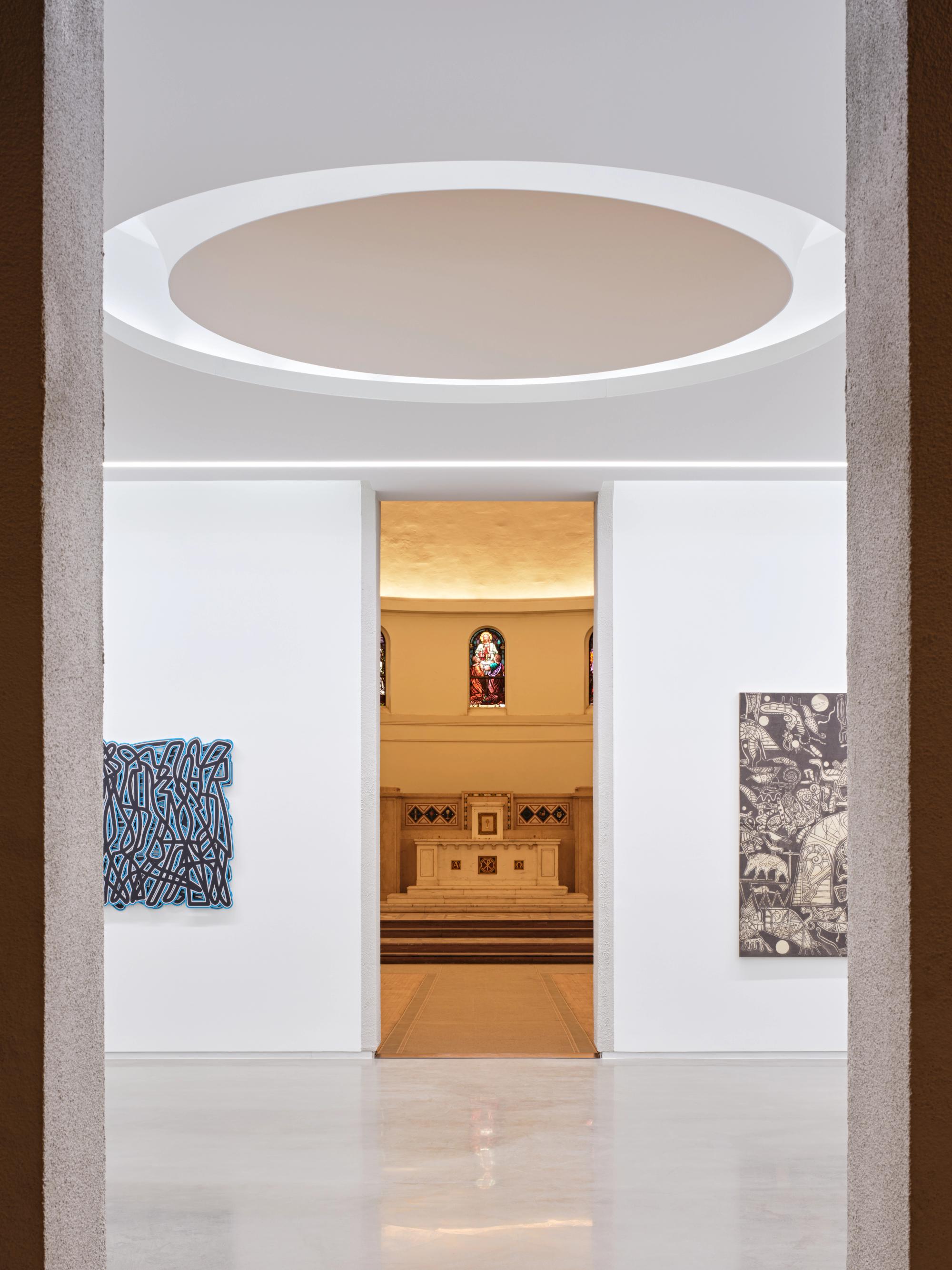

Inside, the transformation is immediate: a crisp white-box gallery nested within the church’s historic shell. The front of the building, once occupied by back pews and offices, has been reimagined as a luminous exhibition space, generous in both scale and light. Above it, a circular oculus opens toward the sanctuary’s original vaulted ceiling. Staircases rise to the roof of this new structure, where visitors can look down through the opening or gaze across the grandeur of the main hall, standing roughly at the height where a choir once sang. During my visit, museum technicians are preparing Seen/Scene: Artwork from the Jennifer Gilbert Collection, an exhibition of 36 contemporary artists curated by Laura Mott and Nick Cave (on view through January 10, 2026). The show underscores The Shepherd’s commitment to visibility and access, core ideas behind both the collection and the space itself.

View into the apse and transepts of the Shepherd. Photo by Jason Keen. Courtesy of Library Street Collective.

Inside The Shepherd. Photo Jason Keen. Courtesy of Library Street Collective.

Installation view into the main gallery at the Shepherd, featuring Charles McGee’s Linkage Series (Blue 2), 2017, and Charles McGee’s Unity III, 2020. Photo by Jason Keen. Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Library Street Collective.

Before moving into the art world, The Shepherd founders Anthony and JJ Curis built their careers around real-estate and finance: Anthony worked at Curis Enterprises, a family-run Detroit real-estate firm active in downtown acquisitions, while JJ worked as an accountant. In 2012 they founded Library Street Collective, merging art and urban regeneration with a gallery that evolved into a civic-minded project producing large-scale public works and neighborhood collaborations across Detroit. In 2019 the couple purchased the former Good Shepherd Catholic Church and transformed its 3.5-acre site into The Shepherd, an arts campus guided by their mission to “utilize the arts to create positive and equitable change in our community.” Working with the city’s Arts, Culture, and Entrepreneurship Office and neighborhood groups such as Jefferson East Inc., the Curises have positioned The Shepherd as both cultural destination and civic anchor. The adaptive reuse design by Peterson Rich Office, the Brooklyn-based firm known for its thoughtful approach to public space, reshapes an institution that once built community around religion into one that now builds community around the arts through the insertion of two gallery volumes that leave the church’s original shell unaltered.

Beyond the main gallery, the campus, designs by Office of Strategy + Design (OSD), includes ALEO, a former rectory turned art-driven bed-and-breakfast and artist residency; the Charles McGee Legacy Park, a sculpture garden honoring the beloved Detroit artist; and It Takes a Village Skatepark, designed with legendary pro-skateboarder Tony Hawk and artist McArthur Binion. Together, these elements make The Shepherd something both reverent and new.

View of BridgeHouse, It Takes a Village skatepark and the Shepherd. Photo by Jason Keen courtesy of Library Street Collective.

View of the Charles McGee Legacy Park and the Shepherd. Photo by Jason Keen. Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Library Street Collective.

The Studio in Cure Nailhouse. Courtesy of Cure Nailhouse.

Cyndia Robinson’s nails are small topographies: pale violet, almond-shaped, encrusted with shiny spheres that catch the light like dew on chrome. Alive and almost organic, they shimmer with both polish and intention. In her hands, adornment becomes an assertion of culture, authorship, and belonging.

Opened this summer in Detroit’s Sugar Hill Arts District, Cure Nailhouse reimagines the familiar nail salon as a social experiment rooted in self-care. A Detroit native and lifelong advocate for access and artistry in beauty, Robinson conceived her first entrepreneurial venture as a hybrid between neighborhood salon and cultural hub, structuring it like an art gallery with rotating exhibitions, artist residencies, and open-studio nights where customers turn into collaborators. At Cure, artists create, mentor, and exhibit alongside ceramics by local artisans and paintings by Detroit artists, expanding the social ecosystem of the salon into a full expression of community, creativity, and care.

The Bar at Cure Nailhouse. Courtesy of Cure Nailhouse.

An example of Cure Nailhouse’s work. Courtesy of Cure Nailhouse.

An example of Cure Nailhouse’s work. Courtesy of Cure Nailhouse.

To realize her vision, Robinson enlisted Tiffany Thompson, founder of Duett Interiors, the Portland-based studio known for its material sensitivity. The name “Duett” captures Thompson’s philosophy: design as dialogue, a duet between client and designer, and trust and intuition. “We wanted refinement with audacity,” Thompson says of her work at Cure. “That doesn’t mean excess. It means every detail matters.” From the street, Cure’s glass façade gives little away. Inside, mauve-plastered walls absorb the light while a long metal bar and inflated Plopp stools by Oskar Zięta reflect it. By morning it serves coffee; by night, champagne.

Even the treatment menu becomes a conceptual proposition. Manicures and gels are termed 2D, 3D, and ephemeral sculpture, a taxonomy that reframes nail work as fine art. I mention that her strategy recalls the entrepreneurial precision of early Starbucks: how a dated, overlooked industry can be reimagined through language and design, shifting perception from service to culture. Robinson smiles and nods, calling it “a new language for beauty.” Cure affirms what many women have always known: beauty is infrastructure. “I wanted to create a space that honors the women who built this culture but were rarely credited for it,” Robinson says. “Black women shaped what beauty looks like in America; this is a place that finally reflects that.”

The Interlude at Cure Nailhouse. Courtesy of Cure Nailhouse.

Inside Cure Nailhouse. Courtesy Cure Nailhouse.

Inside Cure Nailhouse. Courtesy Cure Nailhouse.

Detail view of The Bar at Cure Nailhouse. Courtesy Cure Nailhouse.

Installation view of Everything Eventually Connects: Mid-Century Modern Design in the U.S. at Cranbrook Art Museum. Photo by P.D. Rearick. Courtesy of Cranbrook Art Museum.

From the campus entrance, eight bronze nudes twist and leap through the Orpheus Fountain, their bodies glinting against the pale stone colonnade of the Cranbrook Art Museum beyond. The scene is at once classical and modern, sensual and disciplined, the physical embodiment of the ideals forged by an academy credited as the cradle of mid-century Modernism. It’s hard not to be mesmerized by the beauty and high-minded legacy of those who built, taught, and collaborated on these grounds, shaping one another and, in turn, the wider world. Every detail affirms what can happen when education, craft, and industry share a belief in design as a civic force.

Lyla Catellier, the museum’s Curator of Public Programs, and Amy Auscherman, MillerKnoll’s Director of Archives and Brand Heritage — a walking encyclopedia of postwar design history — tour me around the museum. The exhibition on view, Eventually Everything Connects: Mid-Century Modern Design in the U.S., borrows its title from a Charles Eames maxim: “Eventually everything connects — people, ideas, objects.” Organized by Cranbrook Art Museum Director Andrew Satake Blauvelt and MillerKnoll Curatorial Fellow Bridget Bartol, the survey celebrates the expected chorus of design greats — Ray and Charles Eames, Florence Knoll, Harry Bertoia, Eero Saarinen, Ralph Rapson, Ruth Adler Schnee, among others — yet the curators widen the frame: “While shining a light on figures including women, LGBTQ+ individuals, and designers of color who have been eclipsed in histories of this otherwise irrepressible movement,” the wall text reads, “the exhibition celebrates those who brought warmth, personality, and visual excitement to everyday life.”

As we view Ray Eames’s early abstract watercolors, Auscherman explains how the artist-turned-designer’s avant-garde sensibility disrupted Charles’s industrial precision. “Ray was pursuing modernism years before Charles,” she delights in telling me. “She had danced with Martha Graham and was a founding member of the American Abstract Artists group. Charles’s early architecture in St. Louis was a bit provincial — not great,” she laughs. “But when they met here at Cranbrook, her sensibility collided with his pursuit of industry and structure. Without Ray, Charles might have remained a technician rather than a visionary. She brought the cultural and aesthetic awareness that came to define their partnership.”

Installation view of Everything Eventually Connects: Mid-Century Modern Design in the U.S. at Cranbrook Art Museum. Photo by P.D. Rearick. Courtesy of Cranbrook Art Museum.

The tale captures Cranbrook’s spirit at its most generative: artists and architects cross-pollinating, dissolving hierarchies, and redefining collaboration. And as promised, the show introduces many overlooked figures such as Charles Harrison, a Black industrial designer whose career spanned more than 750 objects, including the ubiquitous pop phenomenon, the View-Master Model G (1958). Harrison later became Sears, Roebuck and Company’s first Black executive. Equally revealing is Edward Wormley, who shared both a home and a studio with designer Edward C. Crouse; together they shaped the 1957 Janus line for Dunbar, a fusion of domestic comfort and Modernist rigor.

As we leave, we run into Leon Ransmeier, a designer and longtime friend and collaborator to both PIN–UP and MillerKnoll. He’s wearing an Ed Ruscha baseball cap that reads BOSS, a wry, possibly accidental nod to his new role. He leads me through his new domain: a suite of serene, empty studios, spaces soon to be reanimated by the next generation of designers. As we walk, he reflects on what lies ahead. “The program I lead was renamed Industrial Design prior to my arrival, a change I welcome,” he says. “The challenge is defining what that means today. I prefer to emphasize a discipline based on collaboration rather than merely thinking about ‘product’ and serial production. It’s about doing things we can’t accomplish as individuals.”

Installation view of Everything Eventually Connects: Mid-Century Modern Design in the U.S. at Cranbrook Art Museum. Photo by P.D. Rearick. Courtesy of Cranbrook Art Museum.

Portrait of Olayami Dabls at the Dabls MBAD African Bead Museum. Photo by Patrick Barber. Courtesy of Kresge Arts in Detroit.

From the street, the Dabls MBAD African Bead Museum looks less built than encrusted, its walls flashing back the city’s light in shards of mirror and clay. For years I’d only seen the place in passing, framed by a car window. On this bright morning, I finally stop. Waiting out front are two Associate Curators from the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit. Abel González and Isabella Nimmo are flushed with excitement. They speak reverently about Olayami Dabls’s forthcoming retrospective. After years of renovation, the Detroit icon’s institutional debut, will reopen the museum this spring marking its 20th anniversary. An elegant Black man joins us. They continue, their admiration so complete that they forget to introduce the newcomer. For a moment I wonder who he is.

The mystery resolves when he turns toward me and says, “Lean in.” His voice is low and deliberate. I do as he says. Dabls begins walking, and we follow him through the sculpture park: mirrored totems, rusted metal, clay figures, and decommissioned cars transformed into art. We stop at an out-of-commission 1980s Craftsman tractor surrounded by a loose circle of old metal chairs. The seats are occupied by slabs of concrete embossed with the outlines of heads, each with hair in dreadlocks. “This one’s called Iron Teaching Rocks How to Rust,” Dabls says, explaining that in African cosmology, iron and rock are spiritual opposites: one changes, the other endures. “It’s a lesson,” he says. “Even the strongest things can learn from time.”

Olayami Dabls, Normal Nudity; watercolors. Courtesy of Kresge Arts in Detroit.

Olayami Dabls, Grand River mural. Courtesy of Kresge Arts in Detroit.

Olayami Dabls, African Language Wall, exterior of the Dabls MBAD African Bead Museum. Courtesy of Kresge Arts in Detroit.

After touring us through each piece, we arrive at the second building that bookends the property. One of Detroit’s old two-story wooden homes, the structure’s siding has been swallowed by layers of paint, glass, bottle caps, and broken tile. On one side, a two-story fish ripples in mosaicked scales; on the other, a striped peacock stands elegantly, feathers at half-mast. Dabls calls the decommissioned home a “decorative vessel.” Each vessel, he explains, is composed of four elements: iron, rock, wood, and mirror, and can be asked to do three things. “I asked that vessel to keep the vandals away, to keep the graffiti off, and to keep the city from seeing it.” The request is practical, although its logic is spiritual: decoration as protection.

At that point, Dabls drops a curveball, pulling us out of the magic of his creations: billionaire developer Dan Gilbert offered to restore this vessel and “transform it into an Airbnb,” he says. An outsider artist who built his own world on the city’s margins is now courted by the very systems he once stood apart from. Dabls embraces both museum and developer as collaborators in the circulation of his ideas; the latter partnership embodies the paradoxes that build today’s Detroit.

Before leaving, we step inside the museum to buy beads, a small token of this encounter to carry home. From thousands of options, I choose a bundle of Howlite skull beads, brightly hued in red, yellow, green, and violet. Dabls himself rings me up, threading the skulls onto a length of yellow cord. The exchange feels like an extension of everything we learned outside: his belief that for him art, labor, and even commerce can be equal forms of communication.

Portrait of Olayami Dabls at the Dabls MBAD African Bead Museum. Photo by Patrick Barber. Courtesy of Kresge Arts in Detroit.