HOPE AND THE URUHIMBI

A RWANDAN FABLE ON SACRED SPACE

by Angela U. Shyaka

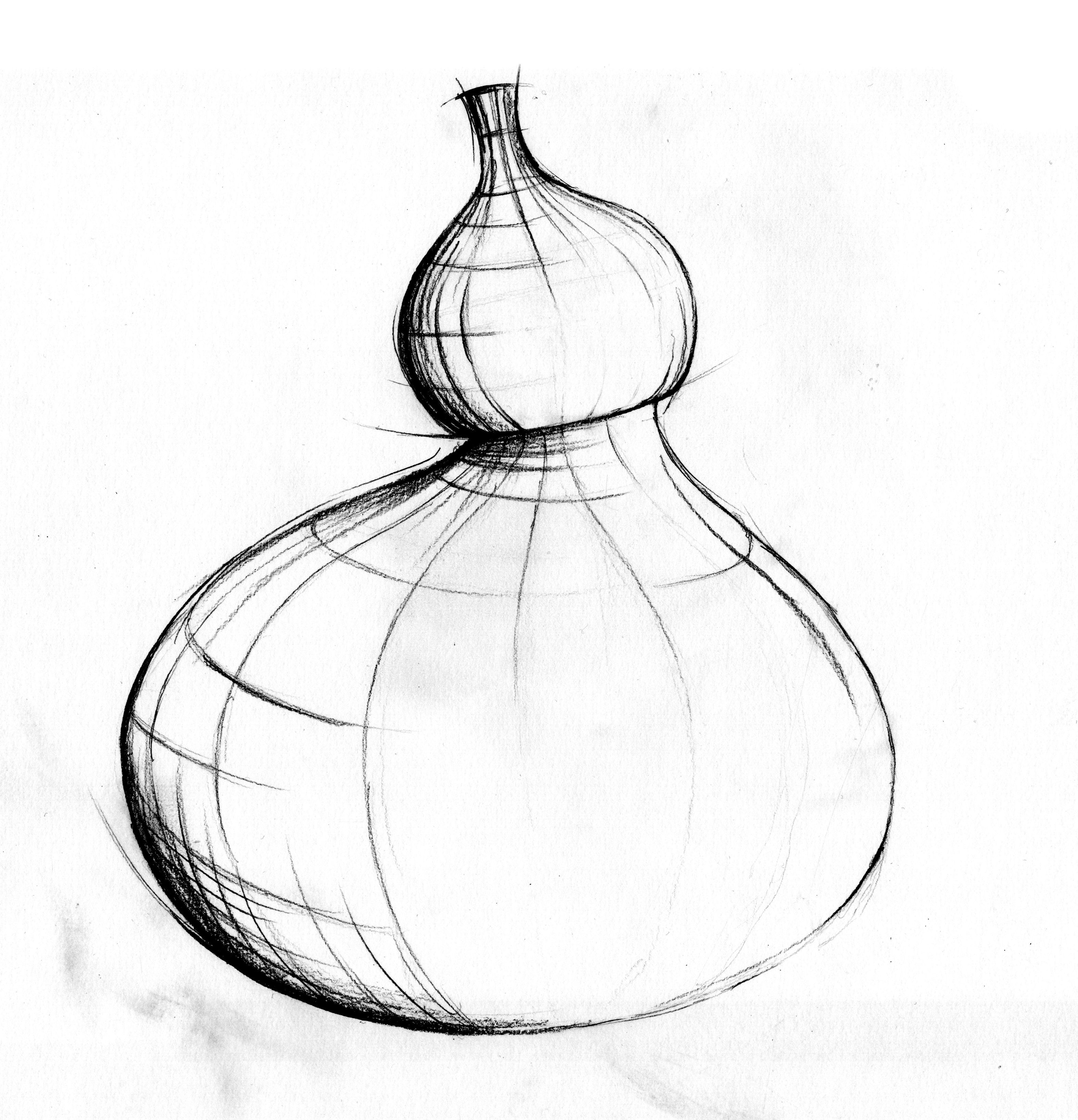

Ibisabo illustrated by Raphael Ganz for PIN–UP and Nieuwe Insituut Design Drafts #2.

It was sometime in the middle of the fourth month, Mata (mah-tah), as we say in my mother tongue, Kinyarwanda. Mata is my favorite month of the year; unsurprisingly so, considering it is named after milk, and I am, after all, a milk gourd. After moving between storage boxes and museum exhibits behind glass, occupying shelving displays at various residences in between, I was finally back where I belonged: the uruhimbi (ooh-roo-heem-bee). A sacred repository of milk and memories. My dear home. Next to me were two inshongero (in-shon-jeh-roh), three ibirere (ee-bee-reh-reh), and two curvy, burnt-orange ibisabo (ee-bee-sah-boh) hanging on a wooden stick mounted to the curved wood-and-thatch wall. We were but a meek representation of what once was. I was grateful, nonetheless.

On this exceptionally sunny day, surprised hums and curious footsteps converged by the sole entrance. Arching his back and lowering his neck as he walked in, a tour guide led a group of young students inside the reconstructed traditional Rwandan house. The students gazed at the ceiling, smiling as they breathed in the enveloping smell of ash, milk, dry grass, and wood. They sat facing my direction.

“We are seated in the center of the home. The wood poles around you support the walls. Rwandans hung banana leaf mats to partition the big open floor plan. The beds behind you were raised to store food and other goods underneath.” The guide stood and approached the altar.

“Let’s look at what’s on this uruhimbi.”

Here we go again.

“The inshongero look like flared skirts and were common in the Northeast. The ibirere came in different sizes and were used to store milk; the ibisabo hung from the umugamba.” He picked me up. “The icyansi (ee-ts-yan-see), such as this one, come with pointy caps.”

Everyone hummed in agreement.

“So, was this like an ancient milk fridge?” one student asked.

Yampaye inka!

“It’s not a milk fridge!” I thought, freezing as I realized that my thought had echoed back to me for the first time in decades. Whose mind am I plugged into?

The guide put me down and kept talking. I searched the room for the expression of terror and confusion that would have been mine if I had a face in the first place.

“Look to your right, human. Milk gourd with the blue, yellow, and green cap.” The girl’s eyes shot wide. I don’t blame her; this was rather surreal.

“The... icyansi?” she thought.

“Yes! The name’s Cyansi. Pleased to meet you. And whose are you?”

“Ehh!” she gasped. The tour guide’s voice faded.

“My name is Kwizera.” Although she seemed nervous, the twinkle in her eyes betrayed a long-held curiosity, sparked by the many stories she’d heard from her parents.

“Kwizera, what would you like to see?”

A pause.

“Help me understand the uruhimbi.” she finally said.

“To understand uruhimbi, one needs to understand Rwandan culture. Let me take you back.”

We arrived in 1885. I jumped down from the uruhimbi and skipped to her side as we watched the scene unfold. A mother was waking her four children behind mat partitions. She made her way to the uruhimbi situated intimately between the parents’ and children’s quarters. She began to shake a big ikirere vigorously, steadying the wide bottom and cap of the container with each hand. The father pulled a bunch of small bananas for his children before sitting in the living space. Two sons sat down next to him while the daughters, kneeling next to their mother, uncovered six small ibirere.

“I’ve never seen them this small before,” she noted.

“You use mugs instead.”

After pouring fresh milk into each cup, the ladies joined the boys on the mats. Kwizera watched as the family ate breakfast together and planned the day ahead. The boys were to assist their father with their twenty-seven cows. The girls were going to help their mother clean and sweep the exterior enclosure of their home.

Later that afternoon, we listened to the exchange between the daughters and their nyogokuru.

“Cows are our wealth,” the grandmother started. “Our dances are inspired by them, our expressions derive from them, and they provide for our families, don’t they?” The girls nodded slowly.

“The uruhimbi is the hearth of the home of Abanyarwanda. We gather in this sacred space to share our milk and history, thus transmitting our culture to the next generation. One day, you will do the same.” The girls nodded again.

Suddenly, we were in a bright room. Kwizera found herself seated on the brown cushions of a wooden sofa. Light penetrated the large, square grated windows, which framed a lush green garden and brick enclosure outside. In front of her were three built-in cement shelves centered on the back wall of the living space. A monochrome television on the middle shelf blasted a children’s program. Above it, a smaller shelf housed a Bible and a framed icon of the Divine Mercy. On the bottom shelf were three pristine ibirere. They looked brand new.

Kwizera looked at the child sitting next to her, his eyes fixed on the French-speaking screen with his feet dangling off the couch. Kwizera’s eyes moved to the ibirere, and then to me.

“No, they do not use them. These ibirere are symbolic.” I answered, knowing her question.

The child’s father came into the living room and turned off the television. He reminded his son about the importance of maintaining his grades to secure a scholarship to a university abroad. The child nodded obediently, standing up and heading to his room. On his way out, he brushed the ibirere with his fingers.

“I wonder if he knows why these gourds are there.” Kwizera thought aloud.

I had one last place to show her.

“Why are we in my living room? We don’t have an uruhimbi.”

“Kwizera?” The tour guide’s voice broke our trance.

Her eyes burst open.

“We have a schedule to keep,” he said.

She nodded, swiftly rising before starting towards the exit. At the foyer, she stopped. “Urakoze, Cyansi,” she whispered to herself before trotting back toward the rest of her class.

“You’re welcome, anytime.”

As the group’s steps faded, I wondered what would happen to me, the story of my ancestors, the heritage of my people, and my land. I wondered what would happen to the uruhimbi, once a ubiquitous feature in many Rwandan homes, now a foreign word for many. In the age of technology and hyper-immediacy, how is culture observed, understood, shared, and reinvented?What is remembered?

Collective memory is as strong as the physical manifestation of spaces. As the uruhimbi encapsulates narratives in its very being, so does language. The challenge for keepers of history today centers around what is remembered, for what is forgotten is lost. Our shared memories, carried in our vocabulary, bind the threads of our identity across generations and play with the balance between past and future. What future will you manifest? As you English speakers say, only time will tell.

Design Drafts in PIN–UP 35.