In my view, the capacity to perceive harmony in an architectural and spatial composition is not culture-specific — in fact the beauty of a new definition of classicism is that it highlights how diverse cultural traditions have interpreted this quest for harmony. Rossi himself implicitly recognized this when putting together the references that constitute his main theoretical work, The Architecture of The City (1966), an attempt to recognize typological and formal patterns to which he ascribed the capacity to construct a global architectural vocabulary built by the intelligence of collectivities over time (even, if in his limited scope, these are still to be found in the cultural context he belonged to).

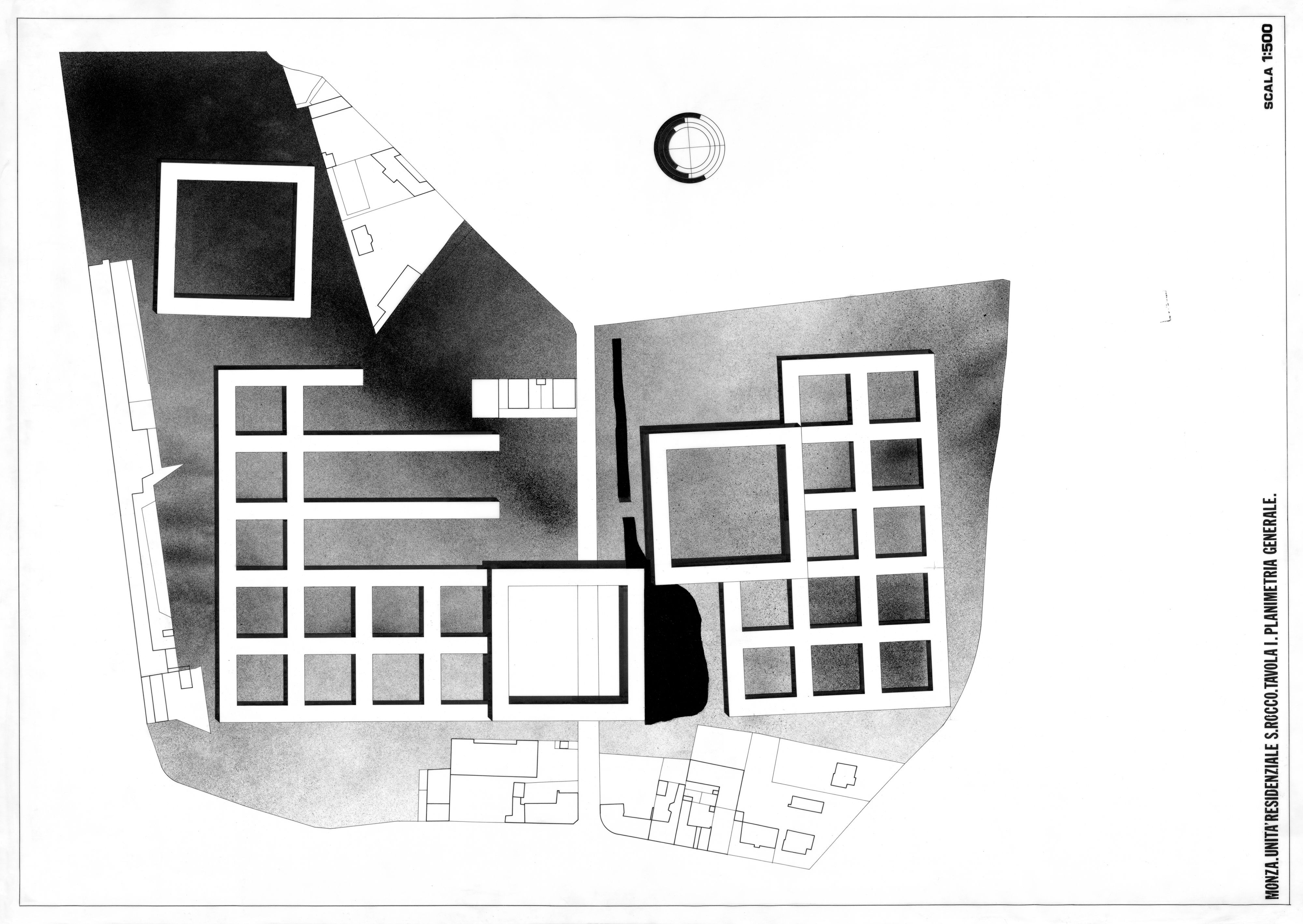

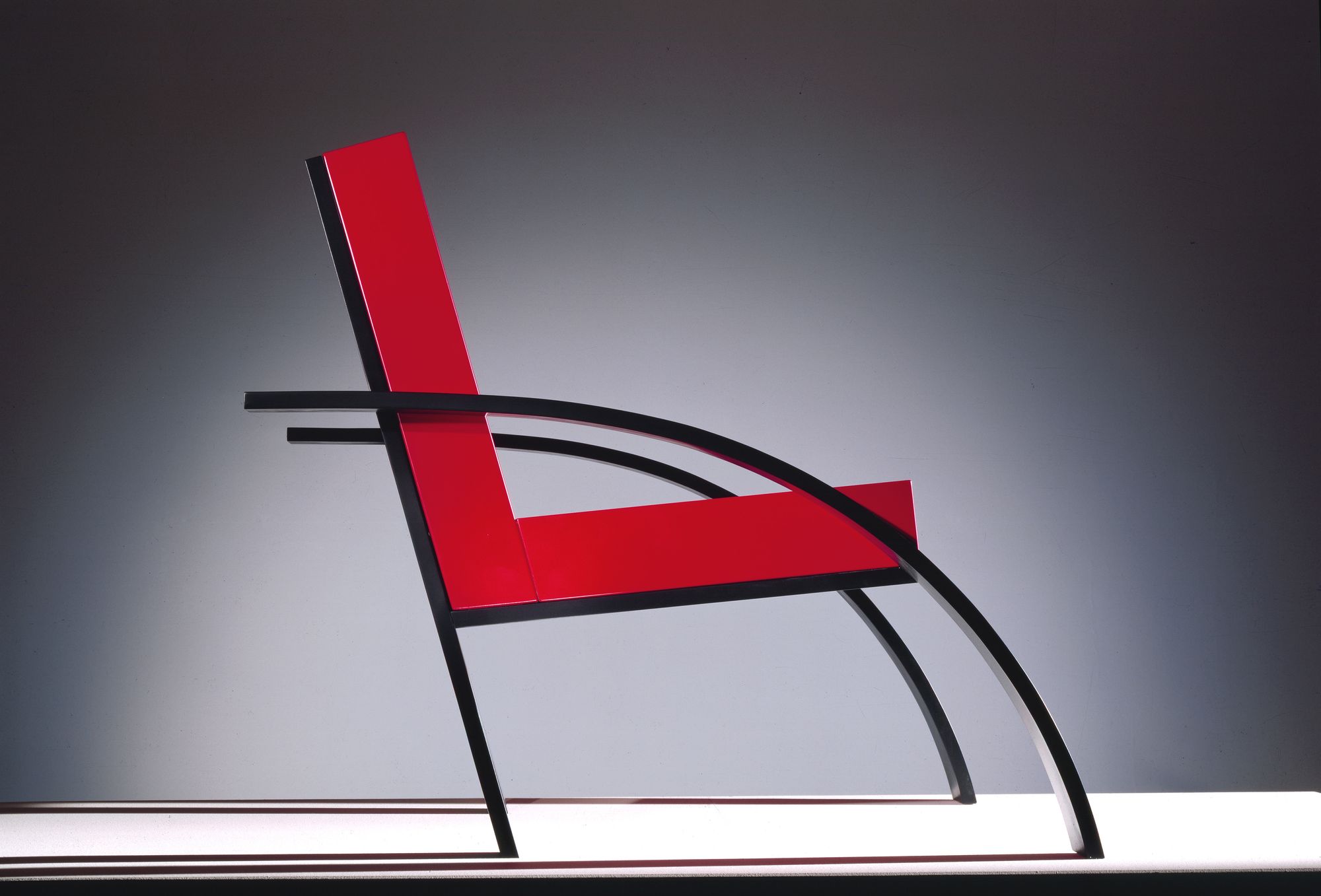

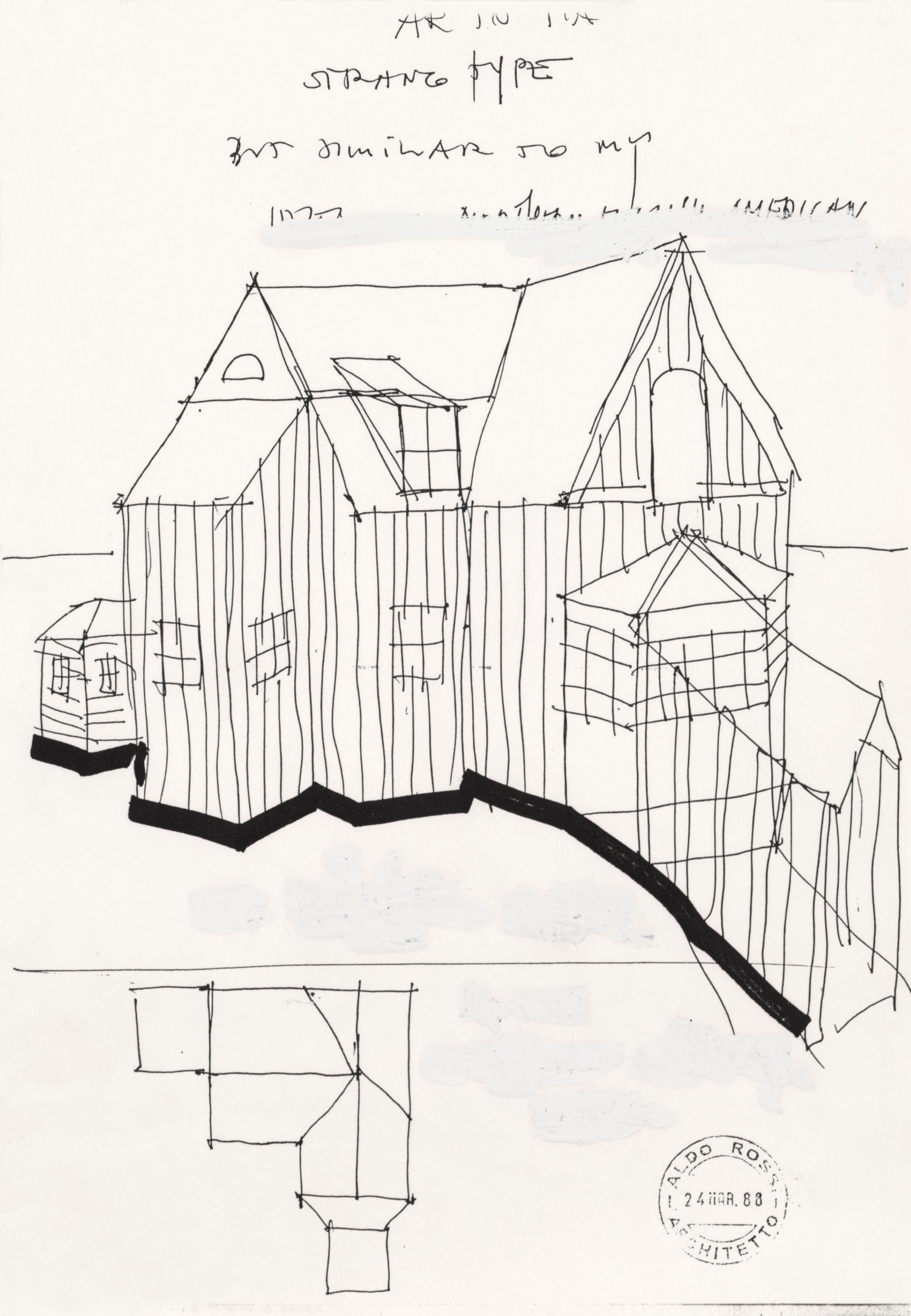

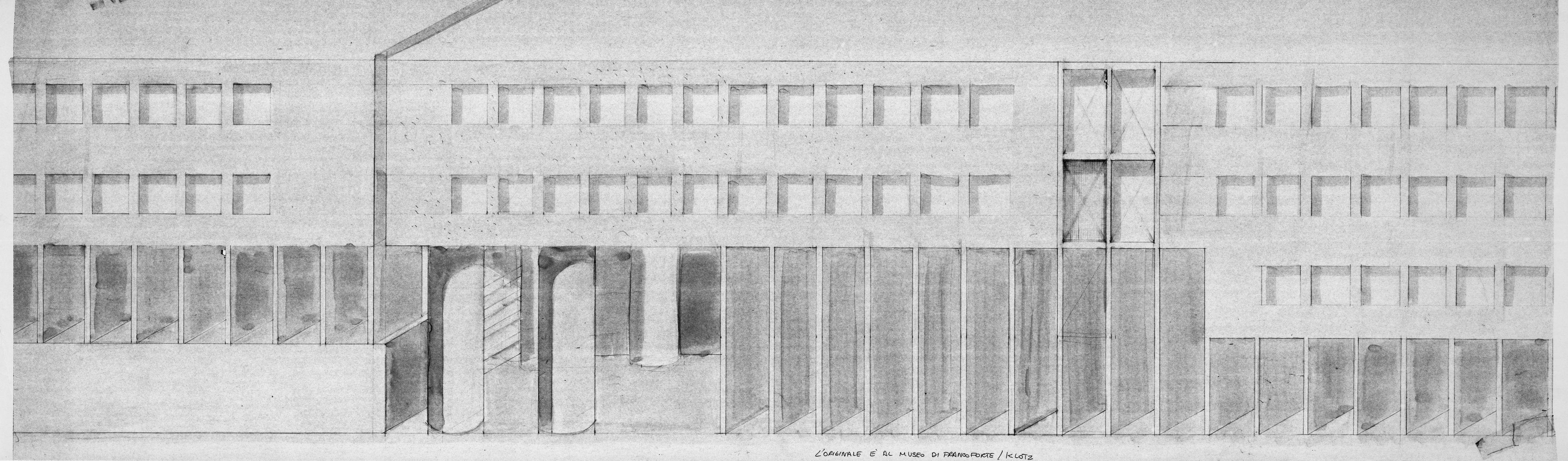

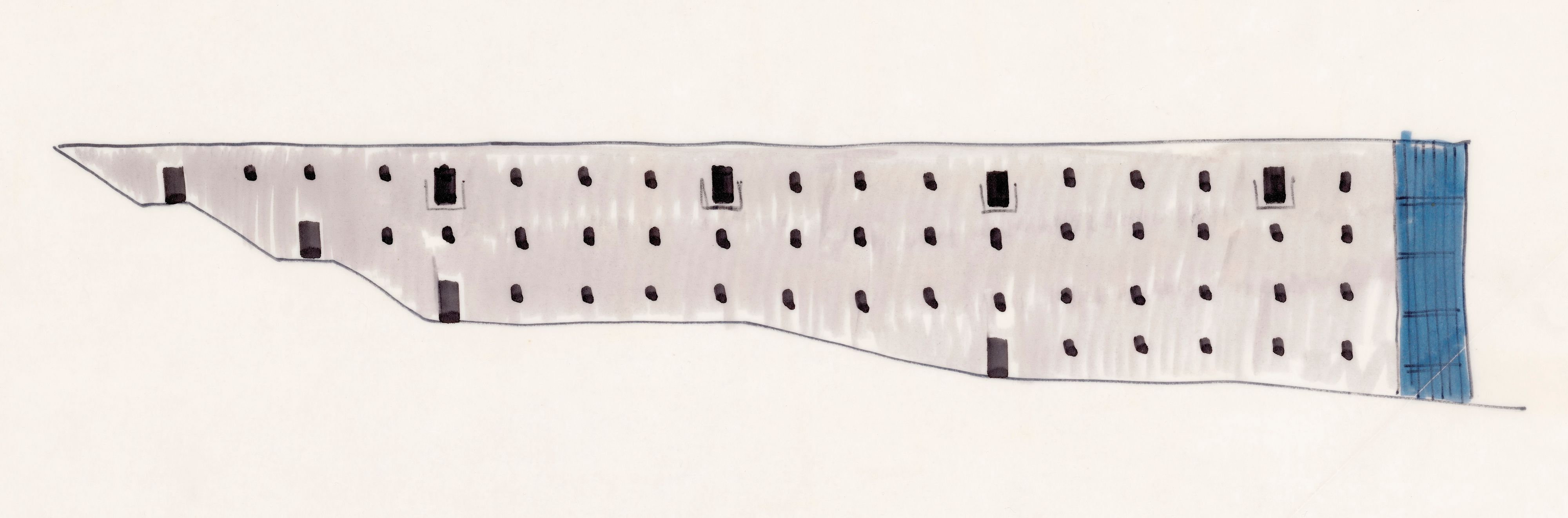

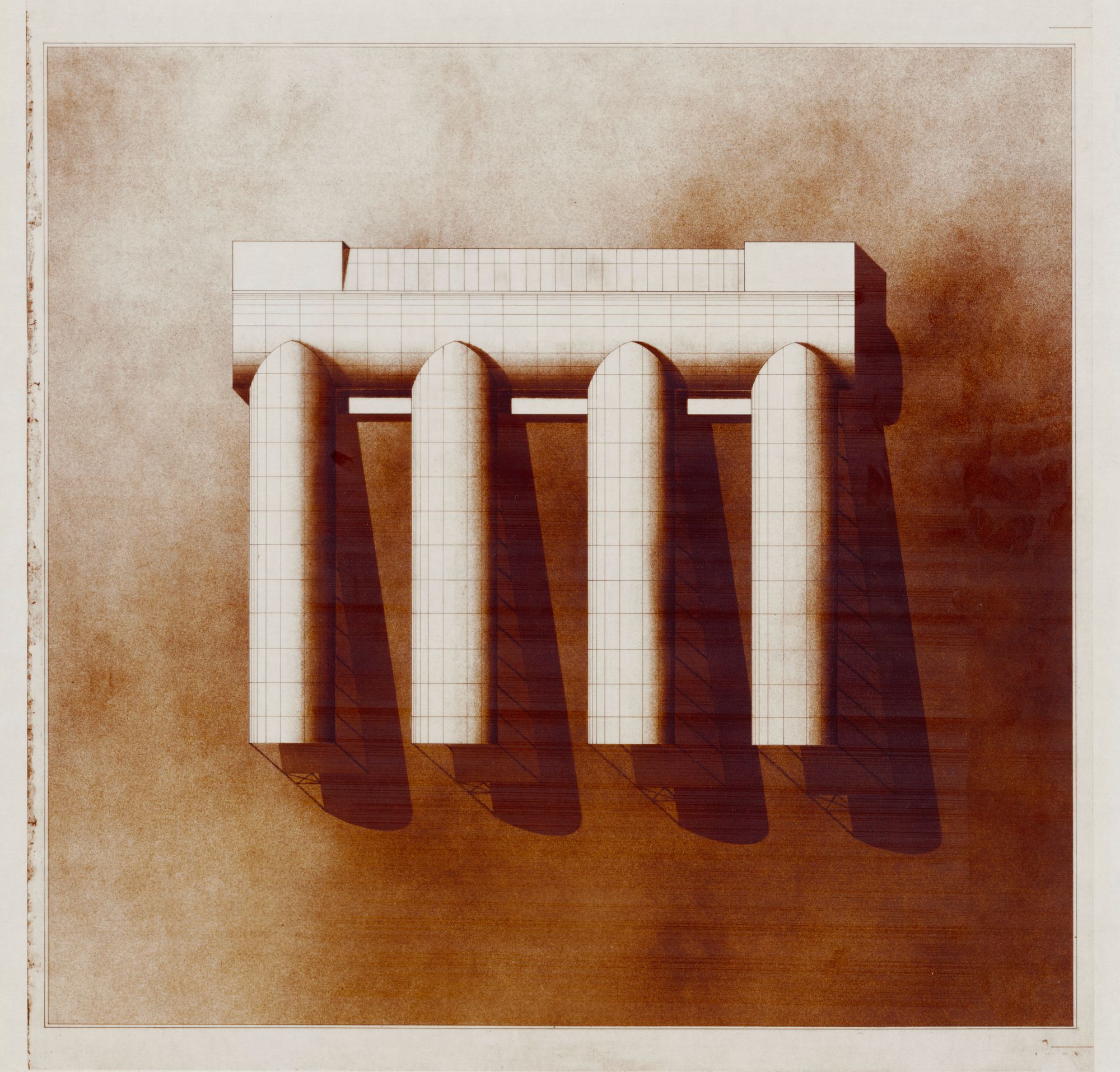

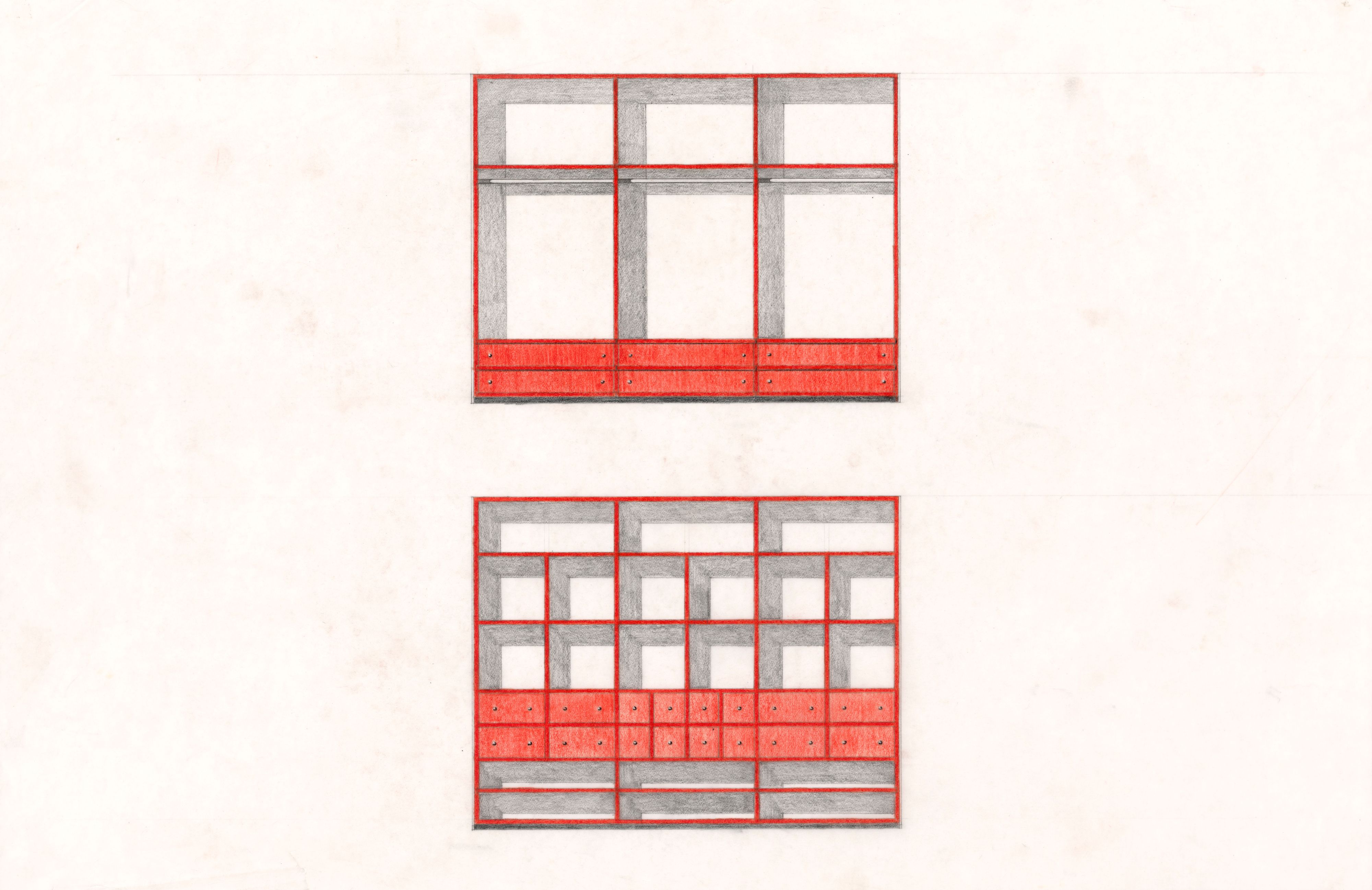

If we generalize Rossi’s method, a theory of design is a question of memory beyond sentimentality, and of intelligence beyond canons. If contemporary architecture has abandoned historicism and pastiche, it cannot do without the fundamental idea that architecture must confront the past, a past understood cybernetically (in the sense of circular causal and feedback mechanisms) as the process of gradual development of shared languages and accepted solutions. This passage is key to the formulation of a theory of design even in the absence of culture-specific proportional and compositional rules. Unlike music, where harmony is measurable, architecture must achieve it by aligning proportion with invention. Here, for me, lies the beauty of Rossi’s early work: instead of importing elements of Classical architecture wholesale, as purveyors of a harmonic composition (a method he adopted in his later career), he attempts to construct it using a few abstract elements combined in ways that aren’t immediately legible as Classical but which possess its essential qualities. Take his competition proposal for the Turin business district (with Luca Meda and Gian Ugo Polesello, 1962), his bridge for the 13th Triennale di Milano (with Luca Meda, 1964), and his Gallaratese housing project (Milan, 1972), all of which feature a limited palette of elements composed with precise elegance: variations of squares and triangles, round and flat columns, thin steel and thick concrete.