CATALOGUES OF DESIRE: An Ode to the Power of Miniatures

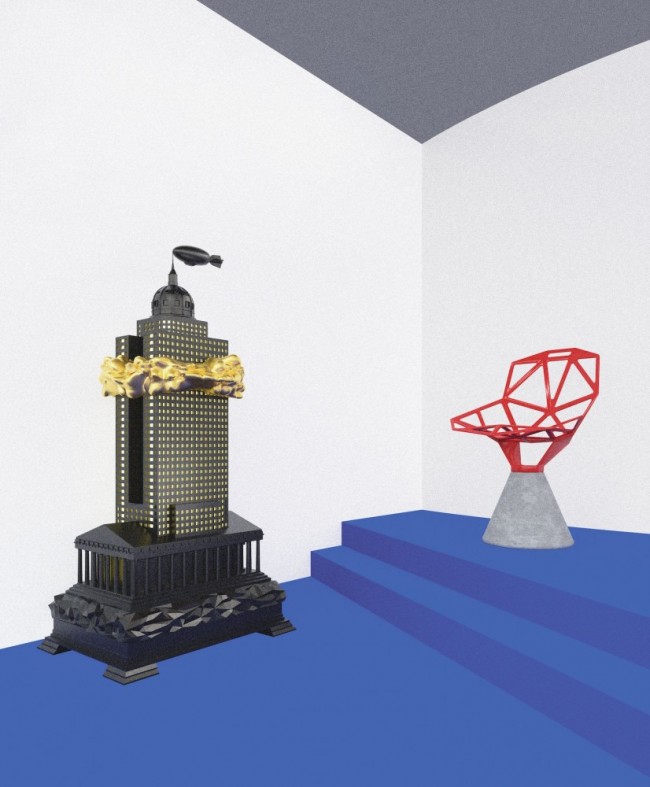

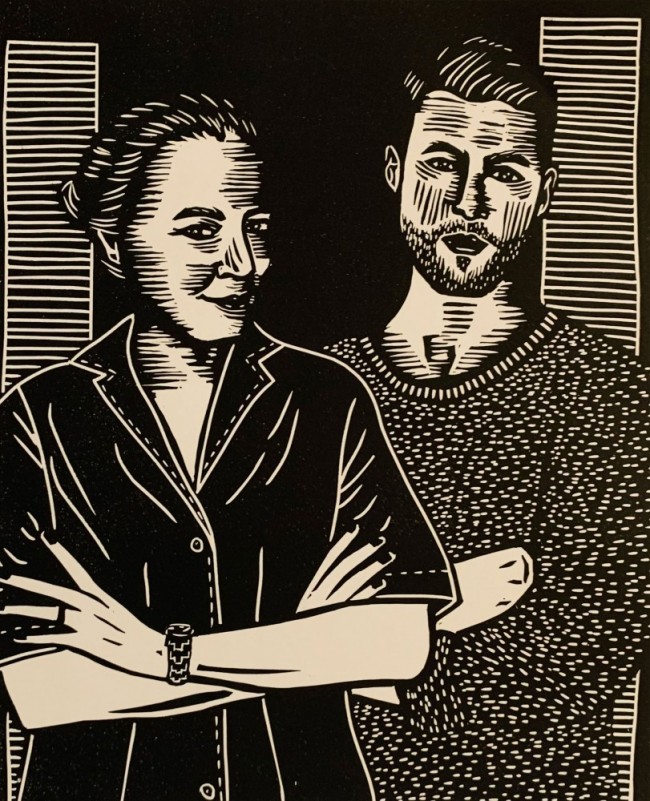

The interior designer Adam Charlap Hyman is one half of Charlap Hyman & Herrero, an architecture and design firm he founded with architect Andre Herrero. Charlap Hyman has amassed research material throughout his life on the subject of miniature interiors and dollhouses. The following text served as inspiration for Charlap Hyman’s design for Blow Up, an exhibition curated by PIN–UP founder and editor Felix Burrichter for Friedman Benda gallery in New York which will be on view from January until February 16, 2019.

-

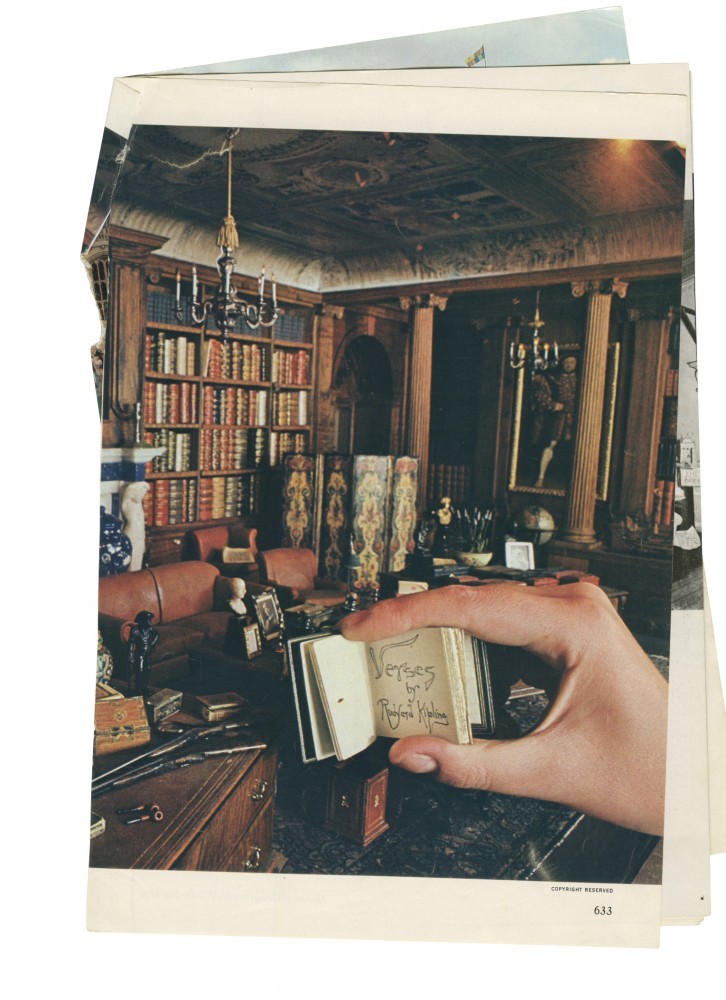

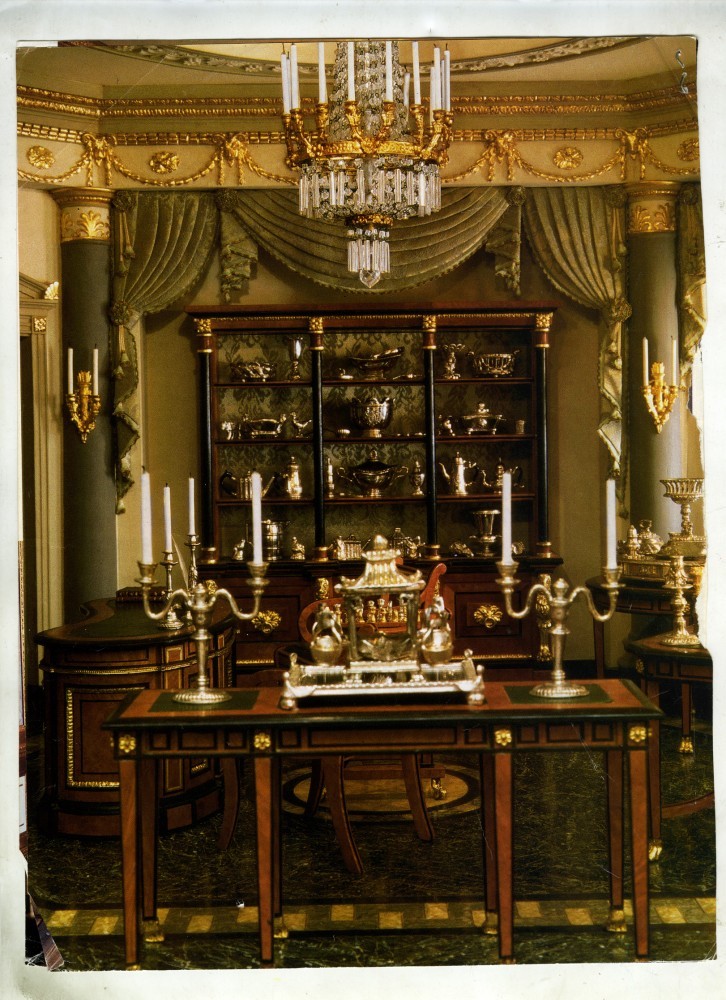

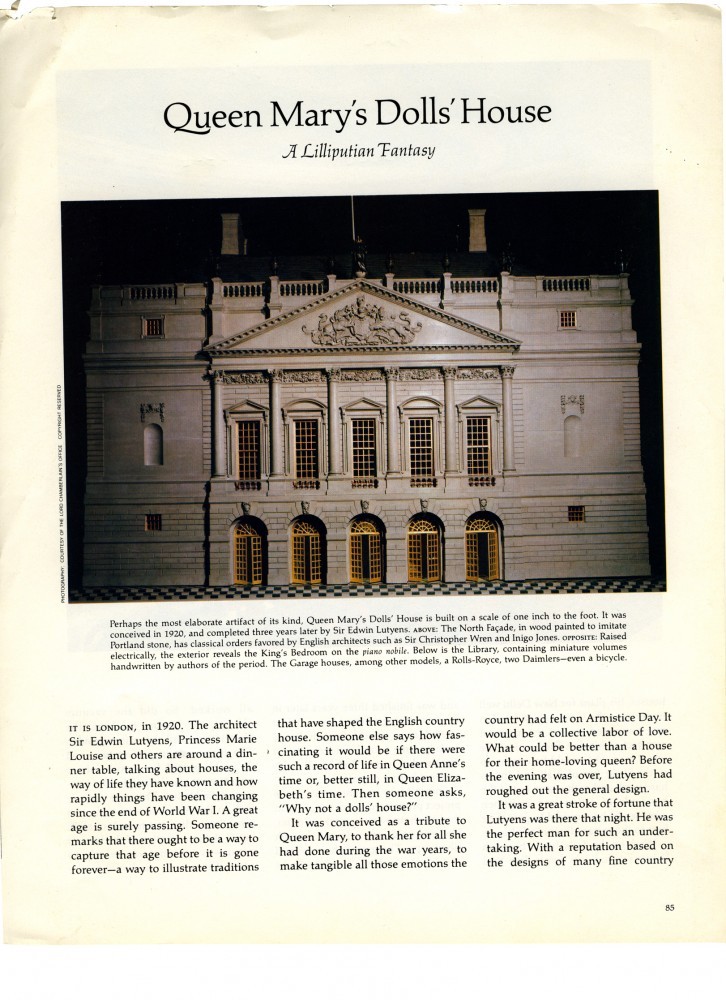

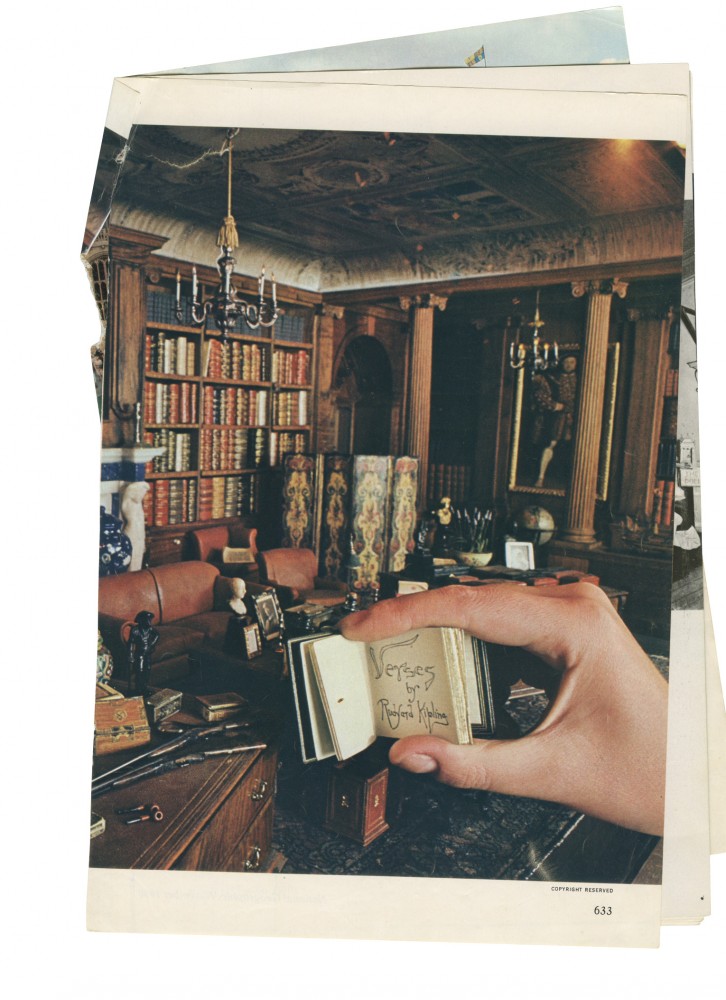

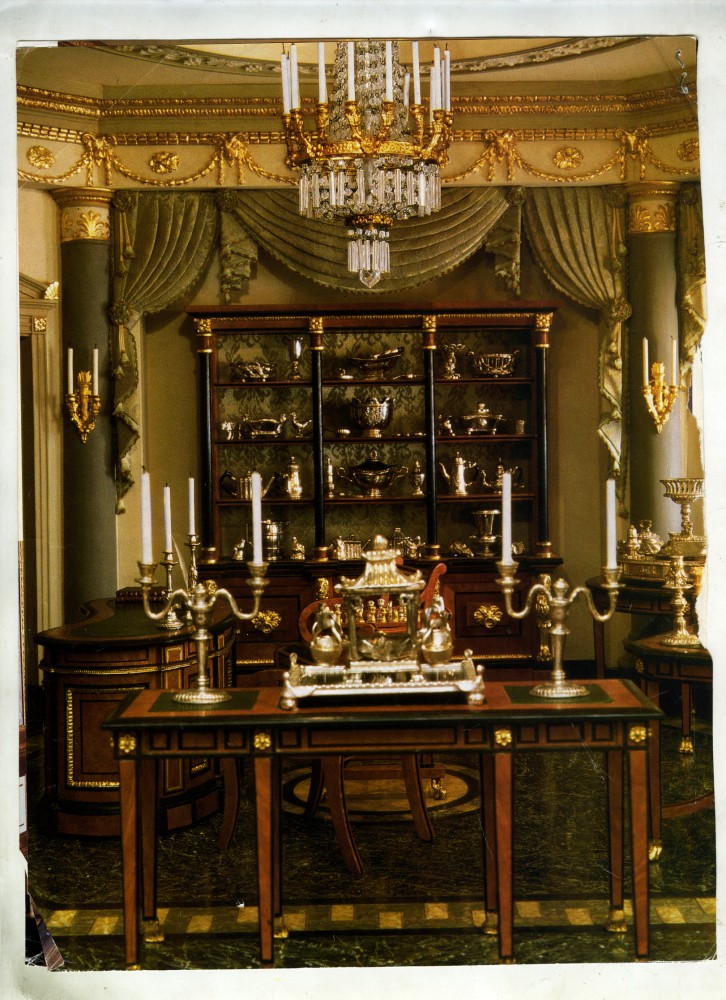

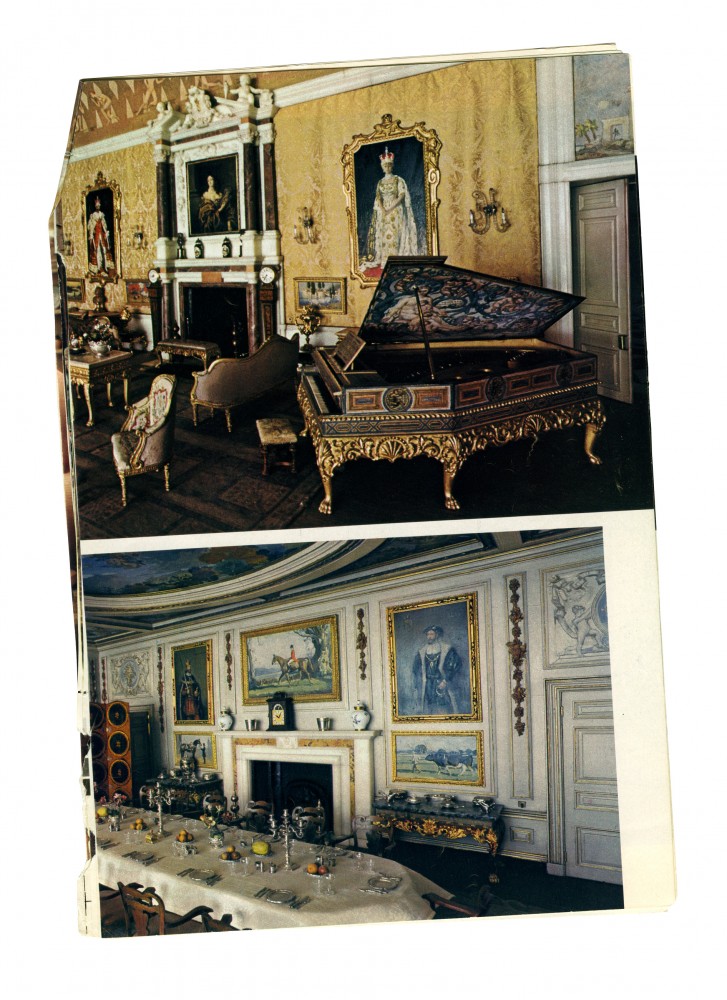

Page from “Royal House for Dolls,” National Geographic (November 1980).

-

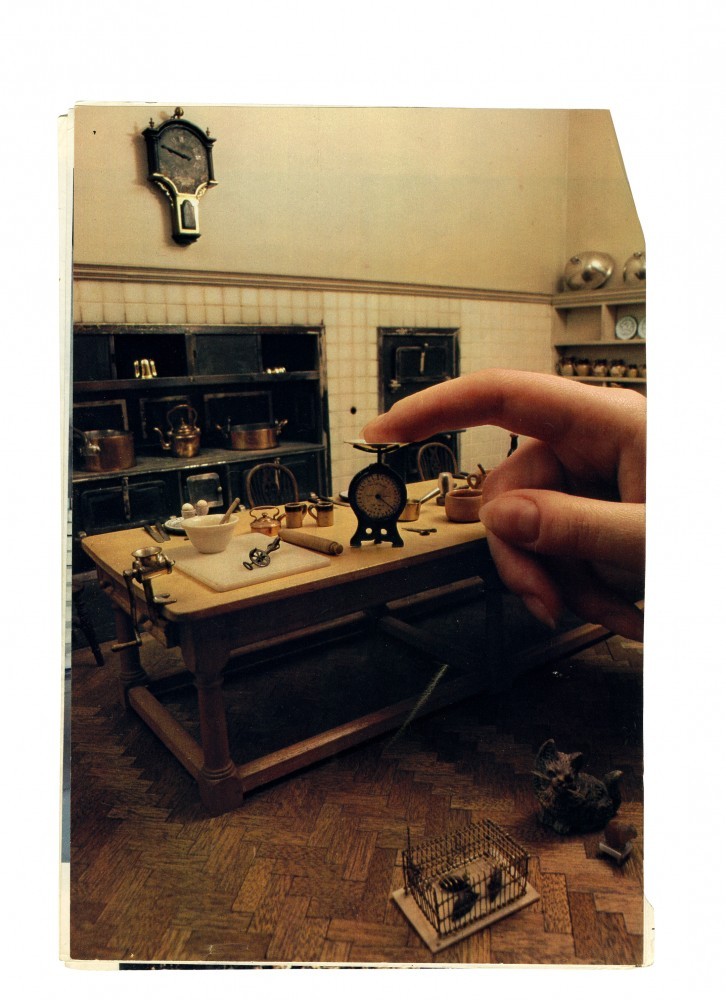

Image from “Small Wonders,” Traditional Home (July 2001).

-

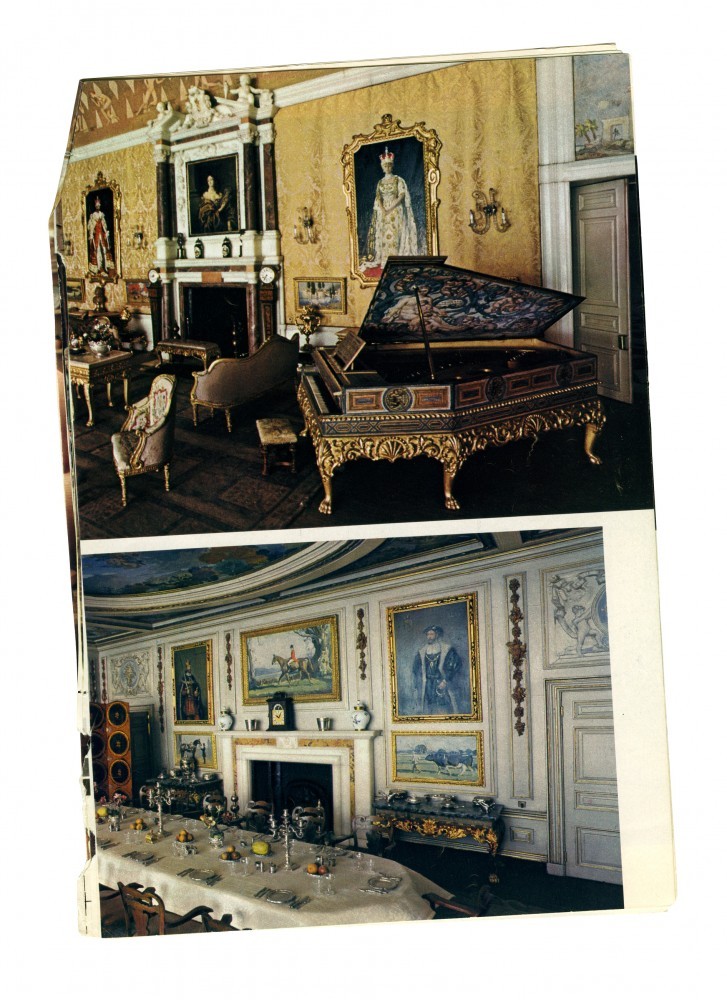

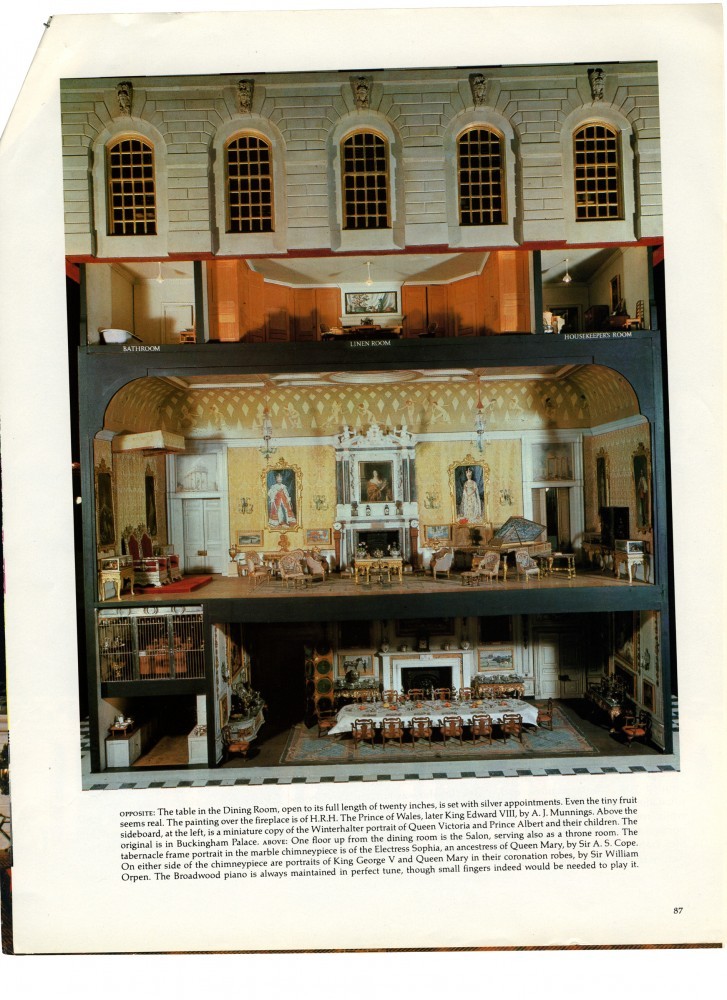

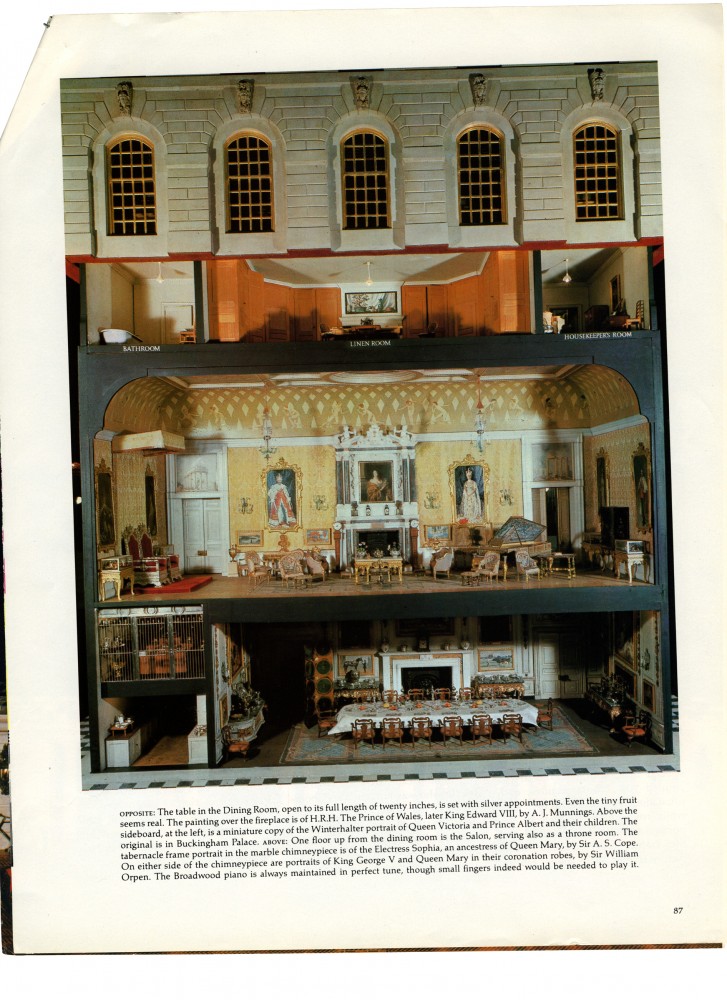

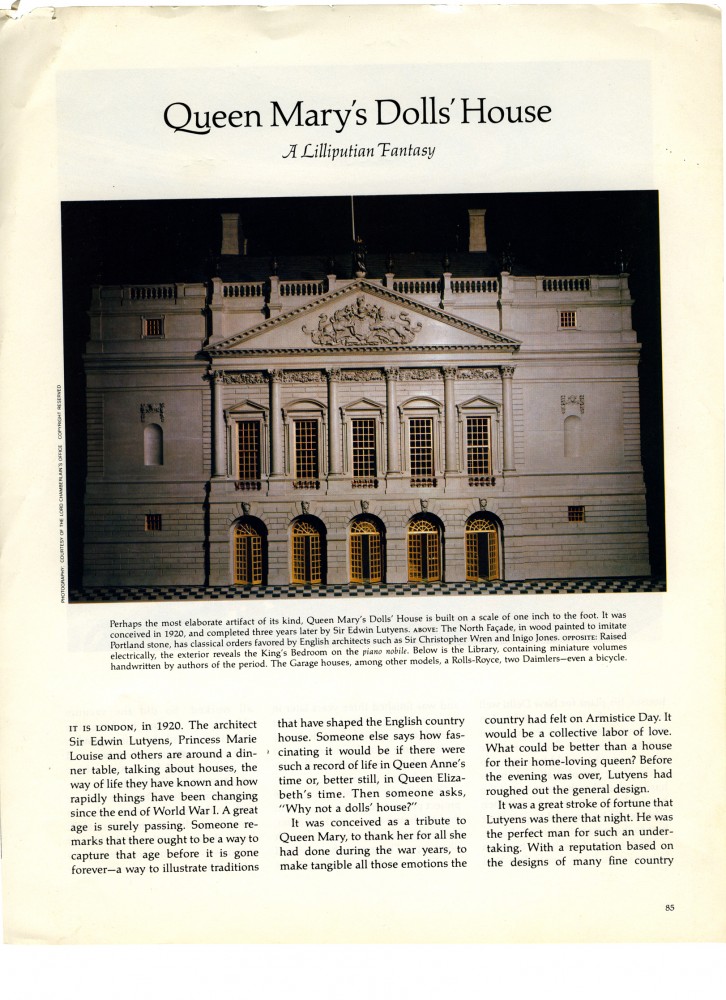

Page from Architectural Digest (c. 1980).

-

Page from “Royal House for Dolls,” National Geographic (November 1980).

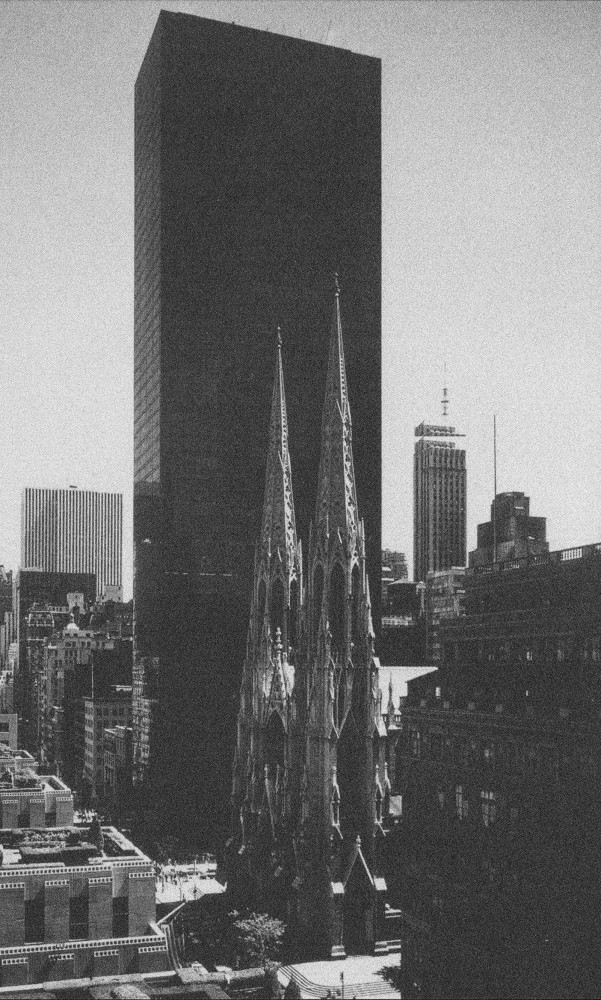

I think my obsession with room miniatures began when I was eight. I had come across photographs in an old National Geographic from the 1980s showing a series of remarkable interiors. There was a library filled with tiny books — each one only big enough to contain the first lines of famous English poems and novels — hand-written in ink by their authors across many small pages. A cellar was stocked with glass bottles filled with wine from the finest vineyards — all labeled and each scarcely an inch tall — sealed with pieces of cork that could only have been inserted with the most delicate of tweezers. In the bedroom, whose walls were hung with luxurious blue damask, matching material was suspended from the bed’s canopy — material which, though probably lighter than a piece of tissue and about the same size, pooled on the floor realistically as though it consisted of yard upon yard of heavy silk. I was mesmerized, and pined away for the visit I would eventually make several years later to see this house — Queen Mary’s Dolls’ House, as it happens, designed by the architect Edwin Lutyens in 1921–24 at 1:12 scale.

-

Cover page for “Queen Mary’s Doll House,” Architectural Digest (c. 1980).

-

Page from “Small Wonders,” Traditional Home (July 2001).

-

Page from “Royal House for Dolls,” National Geographic (November 1980).

-

Page from “Royal House for Dolls,” National Geographic (November 1980).

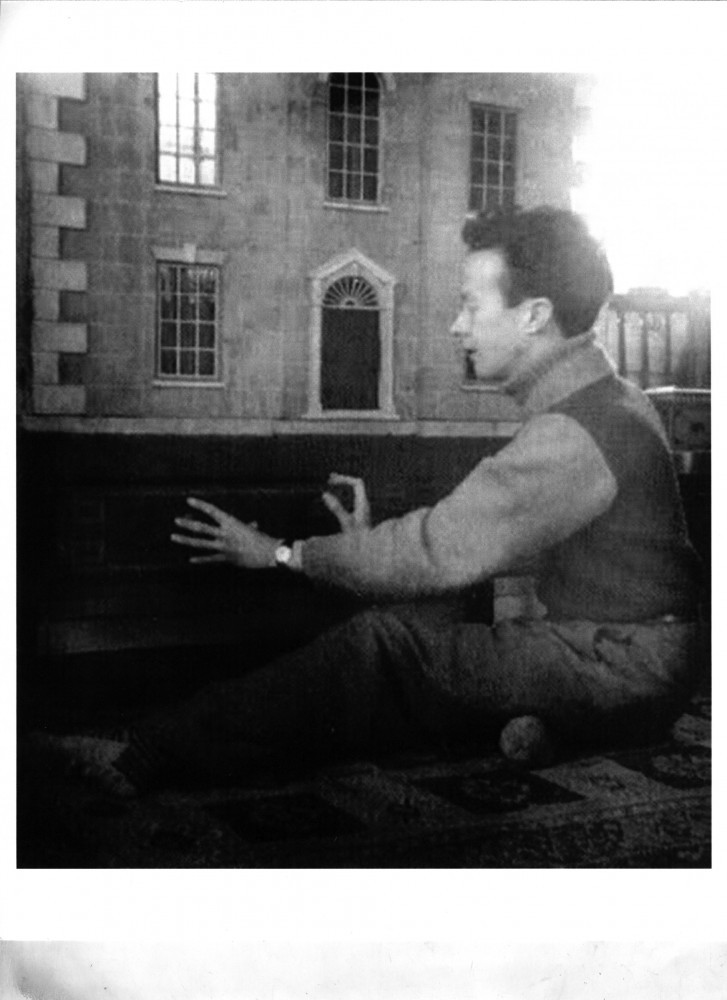

Our pilgrimage to English miniature worlds also took in Titania’s Palace, Sir Nevile Wilkinson’s traveling attraction which was conceived and built between 1907 and 1922 to raise funds for children’s charities. Its inspiration lay with Sir Nevile’s daughter, Guendolen, who at age three fancied she’d seen a fairy disappear beneath a sycamore tree. To accompany his miniature marvel, Sir Nevile published Titania’s Palace: An Illustrated Handbook, whose frontispiece consisted in a photo with the caption “The Architect-in-Chief and her Iridescence” — Sir Nevile himself with a ghostly little fairy perched on his shoulder. To us, now, the image appears goofy and handmade, but somehow the disconnect between representation, reality, and scale was confused.

-

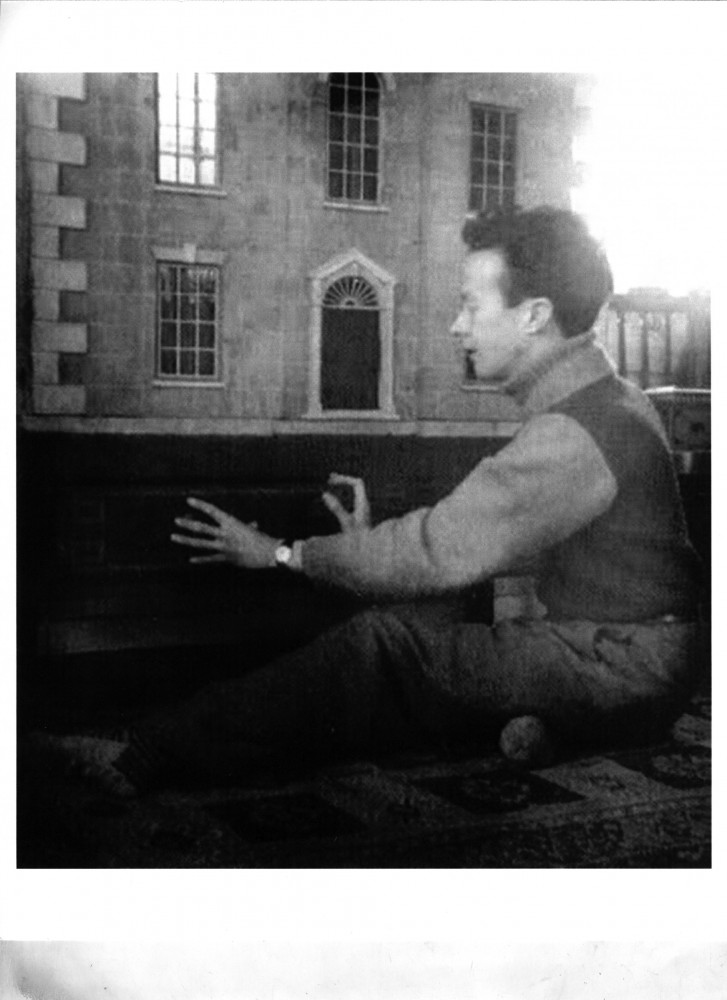

Denton Welch with his dollhouse, from The Paris Review (July 16, 2010).

-

Man inside dollhouse, image from the personal archives of Adam Charlap Hyman.

-

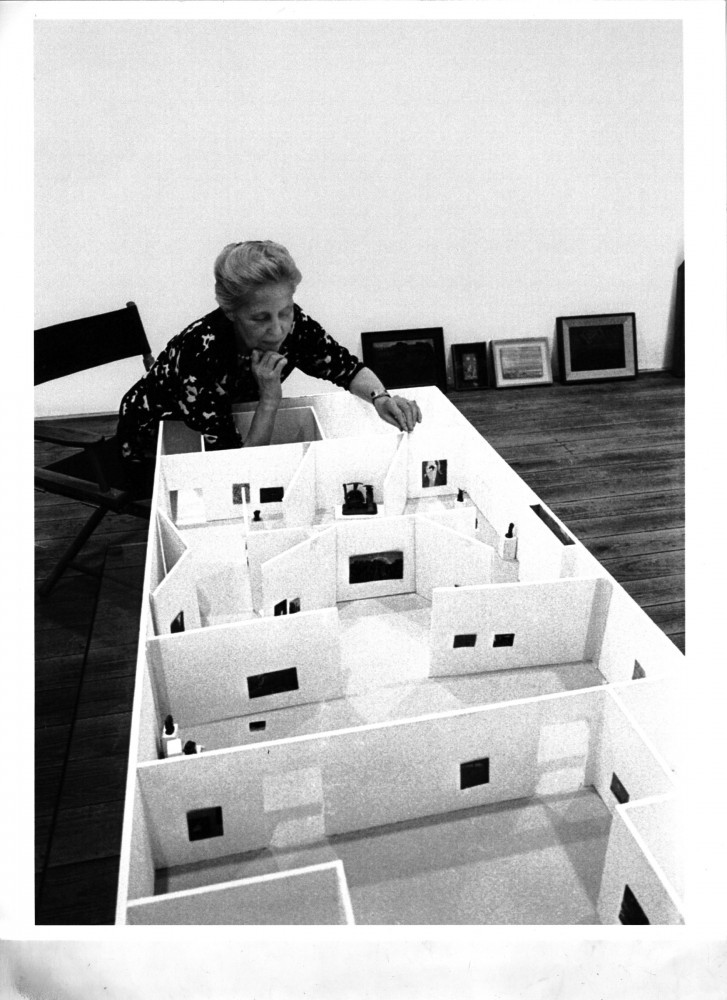

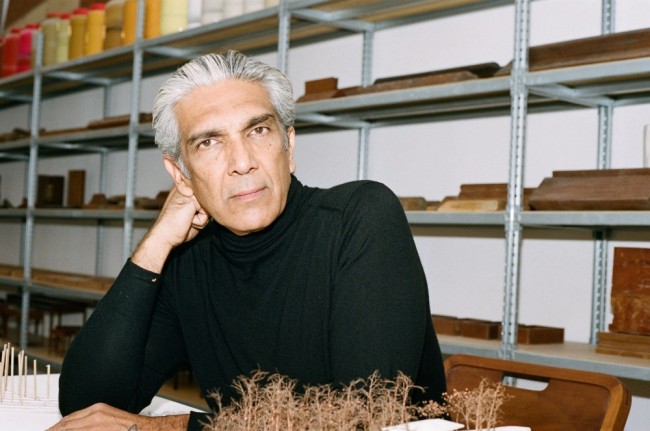

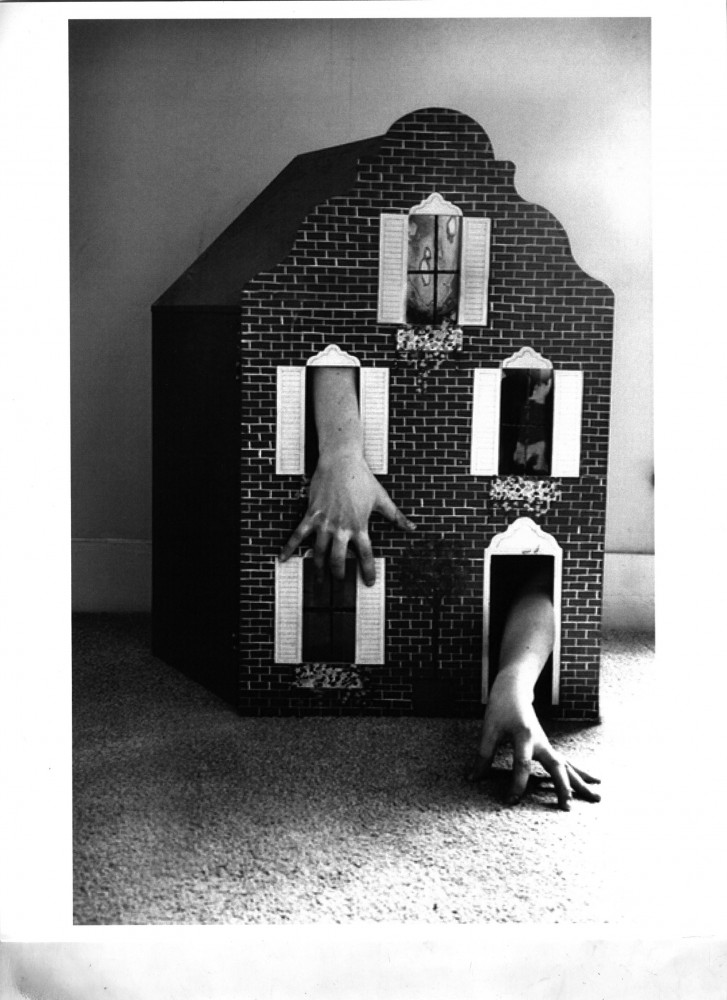

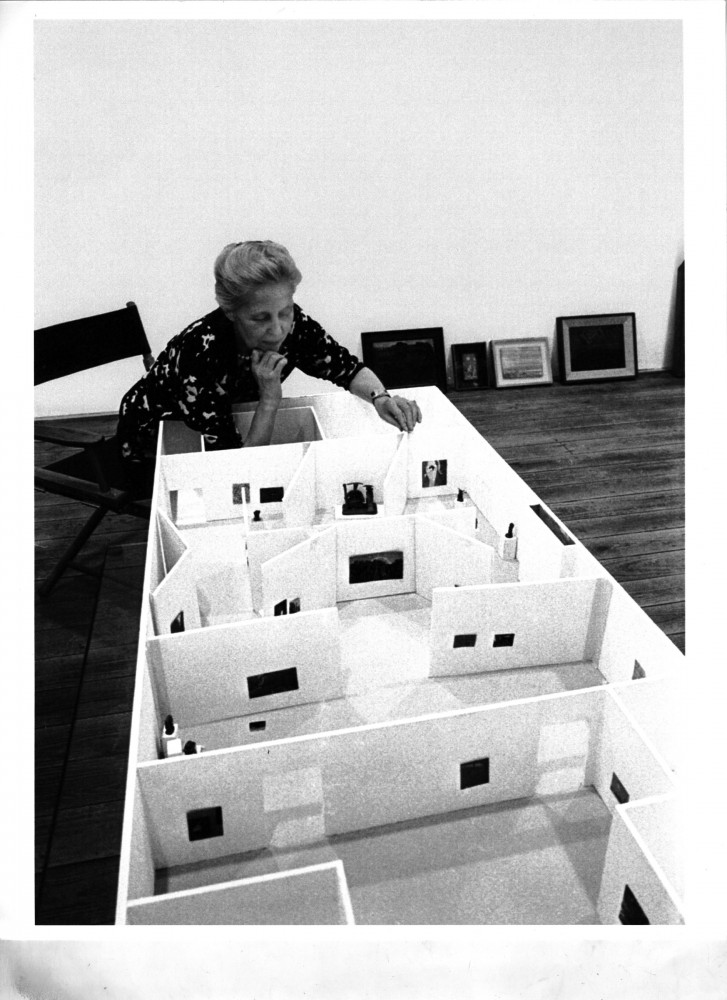

Dominique de Menil with the gallery model for Max Ernst: Inside the Sight (1973), Rice University Museum.

The process by which one’s mind accepts that something is not real and chooses to engage with it seems to me an essential part of making both miniature and full-size architecture. As a kid playing with my own doll-less house, I spent hours arranging elaborate catastrophic tableaux in the kitchen with icing splatter all around the room, shattered porcelain plates, spilled sauces, and grotesque Sculpey meals. I believe my subsequent delight in running around to the façade of the house and peering in at these scenes through the window tapped into something universal: a suspension of disbelief that is so thrilling and pure. Today I feel the same awe when I adjust my vantage point to meet the windows of models that my business partner Andre and I build, and see the spaces inside come to life as the light filters through the openings.

-

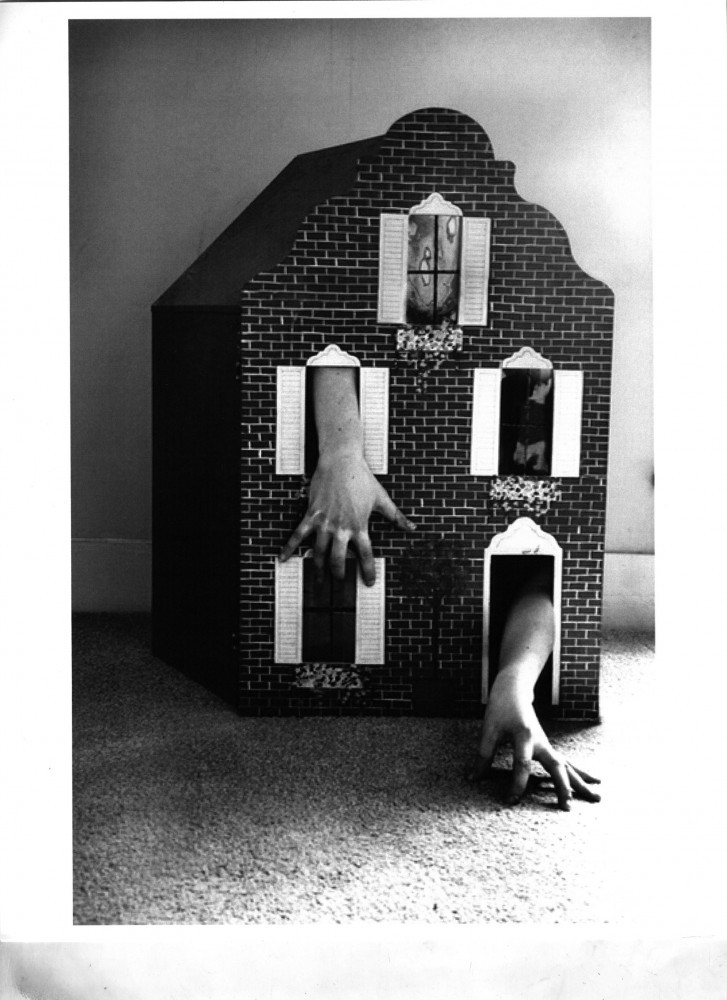

Mae West Lips Sofa miniature from the dollhouse of Edward James (n.d.).

-

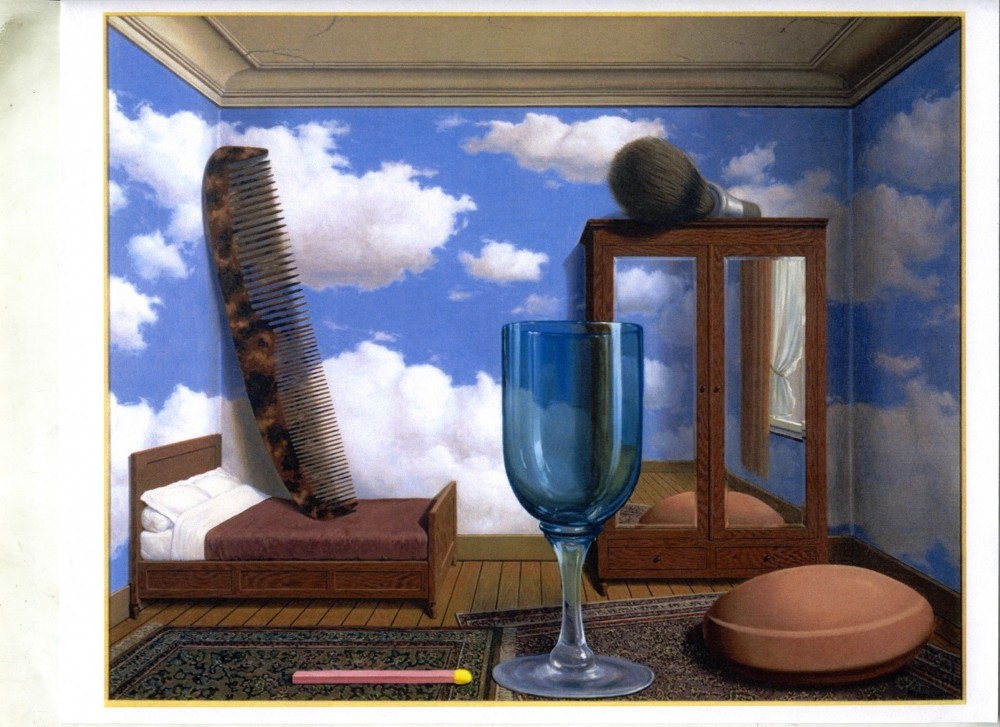

René Magritte, Les valeurs personnelles (Personal Values), 1952.

-

Still from Ingmar Bergman’s film Fanny and Alexander (1983).

-

The Denton Welch dollhouse, England (1783) © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

In the end, on that first trip trekking around England in search of miniature follies renowned for their exquisite and almost uncanny precision, it was the instances where the illusion was fractured that affected me most deeply. We saw the oversized textiles and clumsily rendered china of 17th-century Dutch cabinet houses, which, in all their muddled scale, were made by merchant families to document an ideal of domestic life. We visited Denton Welch’s amateur restoration of a dollhouse rescued from a wartime basement, a diversion from writing and his general sense of not belonging. We ended with the miniature Magritte and ham-fisted upholstery of Salvador Dalí’s lip sofa in Vivien Greene’s Toll House — in the 1980s, Graham Greene’s wife, who was an expert on dollhouses, created a shadow-box tribute to her memories of Edward James’s by-then-destroyed Surrealist interiors at West Dean. Each one we saw was a catalogue of desire, their diminutive scale impossibly weighted with longing, loss, and memory.

Text by Adam Charlap Hyman.

All images from the personal archives of Adam Charlap Hyman.