Cat Snodgrass photographed by Evelyn Pustka for PIN–UP.

Lying on top of her 2022 Perforated Rug, Designer and Bi-Rite founder Cat Snodgrass is lifting Container of Mass, a 20-lb stone dumbbell she designed for Sized at Frieze Week 2022 in Los Angeles. Portraits by Evelyn Pustka for PIN–UP.

“There’s Buy Rite liquor, Buy Rite pharmacies, Buy Rite clothing... I loved the genericness of the name,” says Cat Snodgrass, founder of Bushwick-based design hub Bi-Rite. Snodgrass’s vision for Bi-Rite, however, is anything but generic. What started in 2015 as a store for vintage design has evolved into a retail platform with a distinct aesthetic and its own line of products, many of which were designed by Snodgrass herself, including rugs, mirrors, plates, and more. Soft greens and pinks dominate the minimal color palette, but a utilitarian edge and chrome finish prevent it all from turning saccharine or millennial cute. Think Robert Irwin and the art of the Light and Space movement, rather than Glossier. Snodgrass moved to New York from the Bay Area and first got a start in the music industry before discovering her passion for design. PIN–UP met with the rebel entrepreneur at another moment of transition: in addition to her work with Bi-Rite, Snodgrass is increasingly taking on interior and exhibition design projects and venturing into personal sculpture.

Cat Snodgrass photographed by Evelyn Pustka for PIN–UP.

Cat Snodgrass holding Higher Plate, 2023; ceramic. Portraits by Evelyn Pustka for PIN–UP.

Felix Burrichter: Why did you start Bi-Rite?

Cat Snodgrass: Out of pure necessity. I had just quit my job in the music industry, and I realized that I needed to do something to put a roof over my kid’s head. At the time, a lot of vintage furniture stores were following a very traditional template. And I thought it was an interesting opportunity to do something new. There weren’t many stores catering to this younger audience that was getting into design for the first time in a more academic way.

What was the hottest-selling item in 2015?

We were dealing in a lot of vintage and reissues from the space age, and just starting to lean into postmodernism. Also, Italian radical design, Joe Colombo, etc. I saw it as an opportunity to be adventurous, in the same way as Italian design movements were. There was an incredible response to that. And there was suddenly this supply and demand issue. I felt we could work with contemporary designers and get into production to keep up with demand. It was very successful. But the second I sense that something has been done before or is being repeated, I don’t want anything to do with it. I had to recalibrate quickly. [Laughs.]

It’s that tension between giving people more of what they want to sustain a business, but also giving them something new. And creating something exciting for yourself.

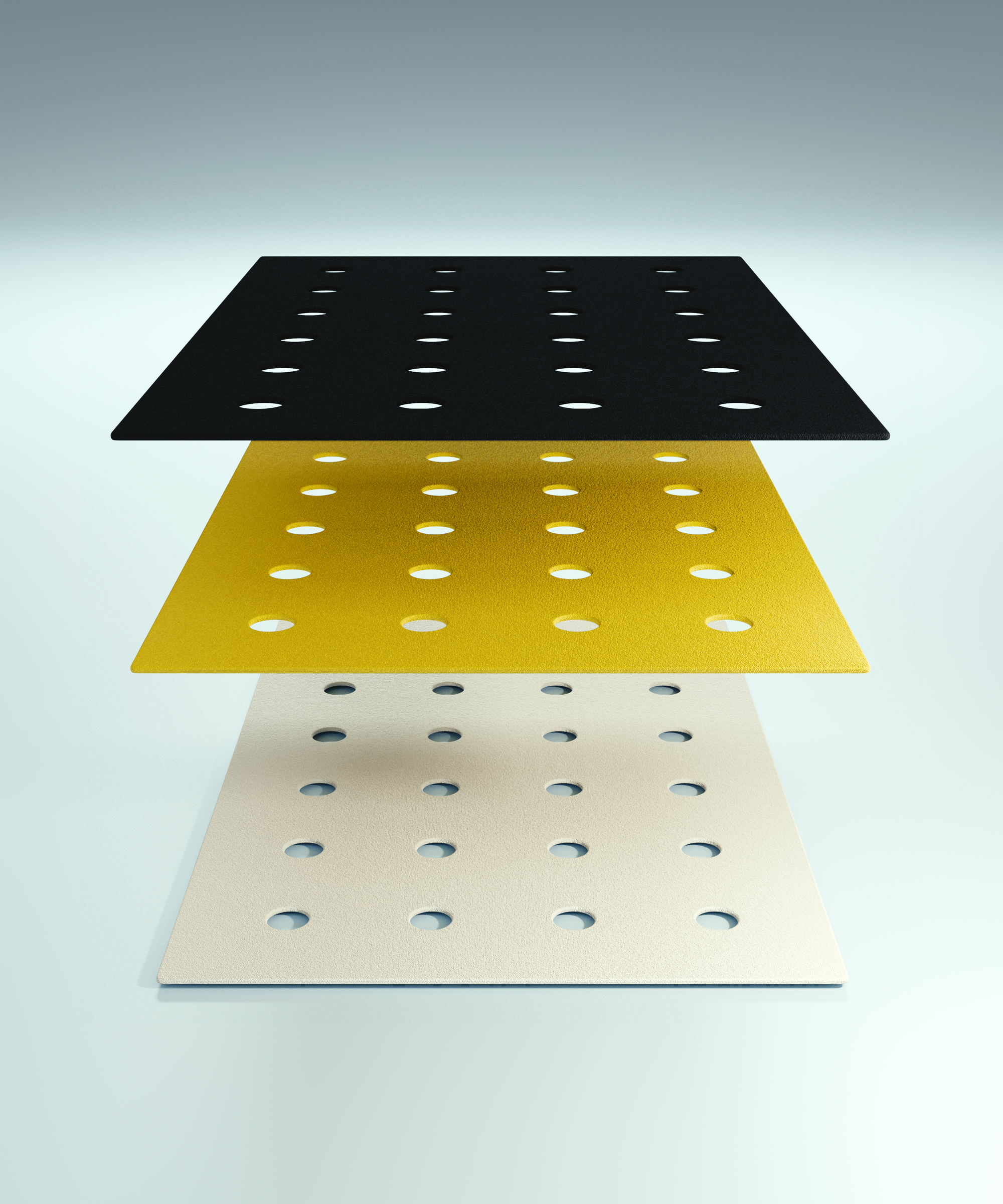

Yes. Around that time, I started thinking, how does a designer actually create something unique? I started to intellectualize this further and think about the millennial aesthetic. What if I did the exact opposite of that? How much can I take away from design until I arrive at something unique? I had never thought of myself as a designer, but it was through exercising this muscle, I discovered there was something there. And that’s how I arrived at the Perforated Rug. It felt fresh to me, playing with negative space almost to a degree that felt stupid. It’s this process of reduction, stripped of all its ornamentation. I just put holes in it. If you think about what iconic design is, it is something that has never been done before. It solves a problem or is the first to arrive at a specific form.

Was the Perforated Rug your first design?

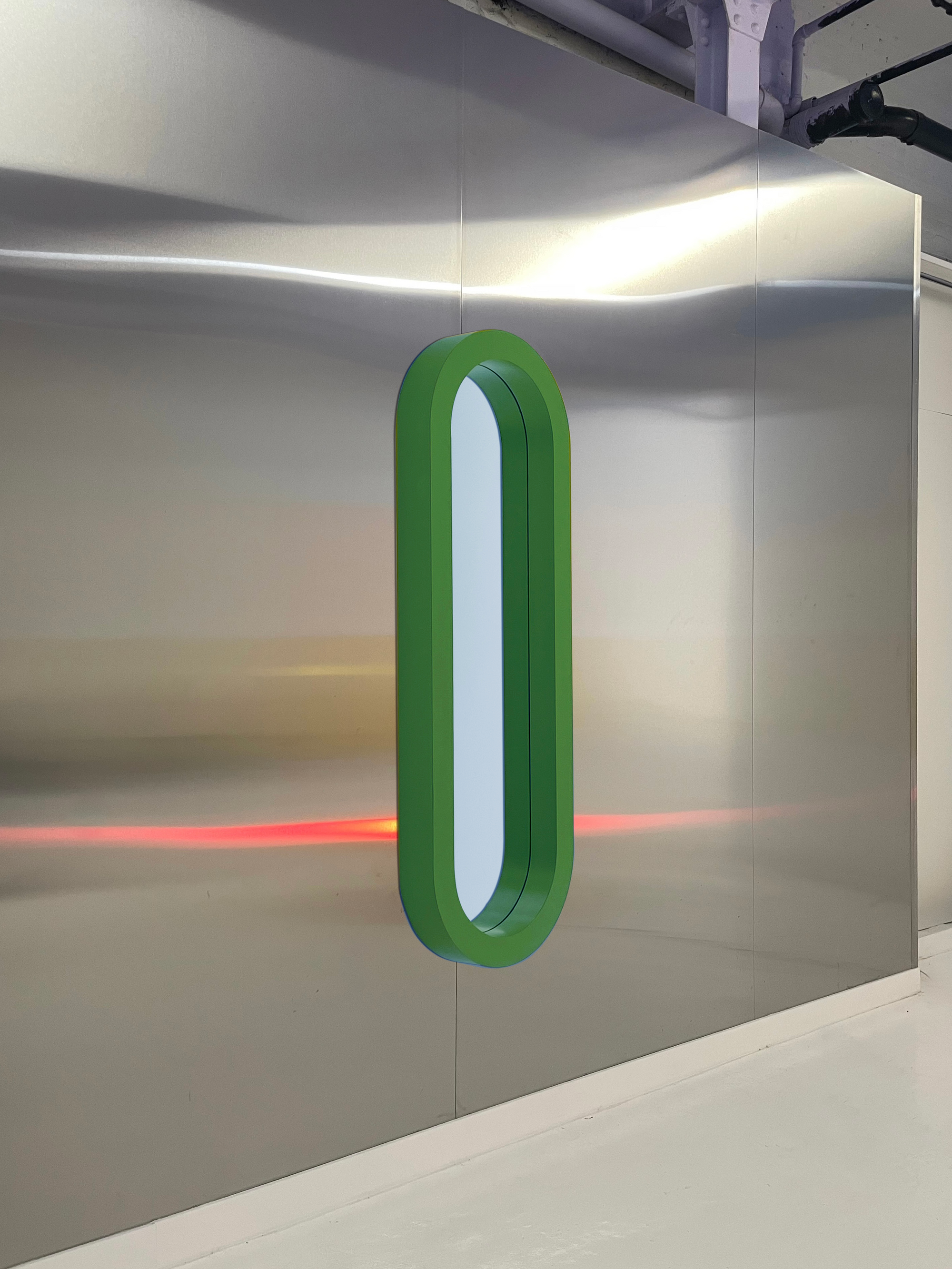

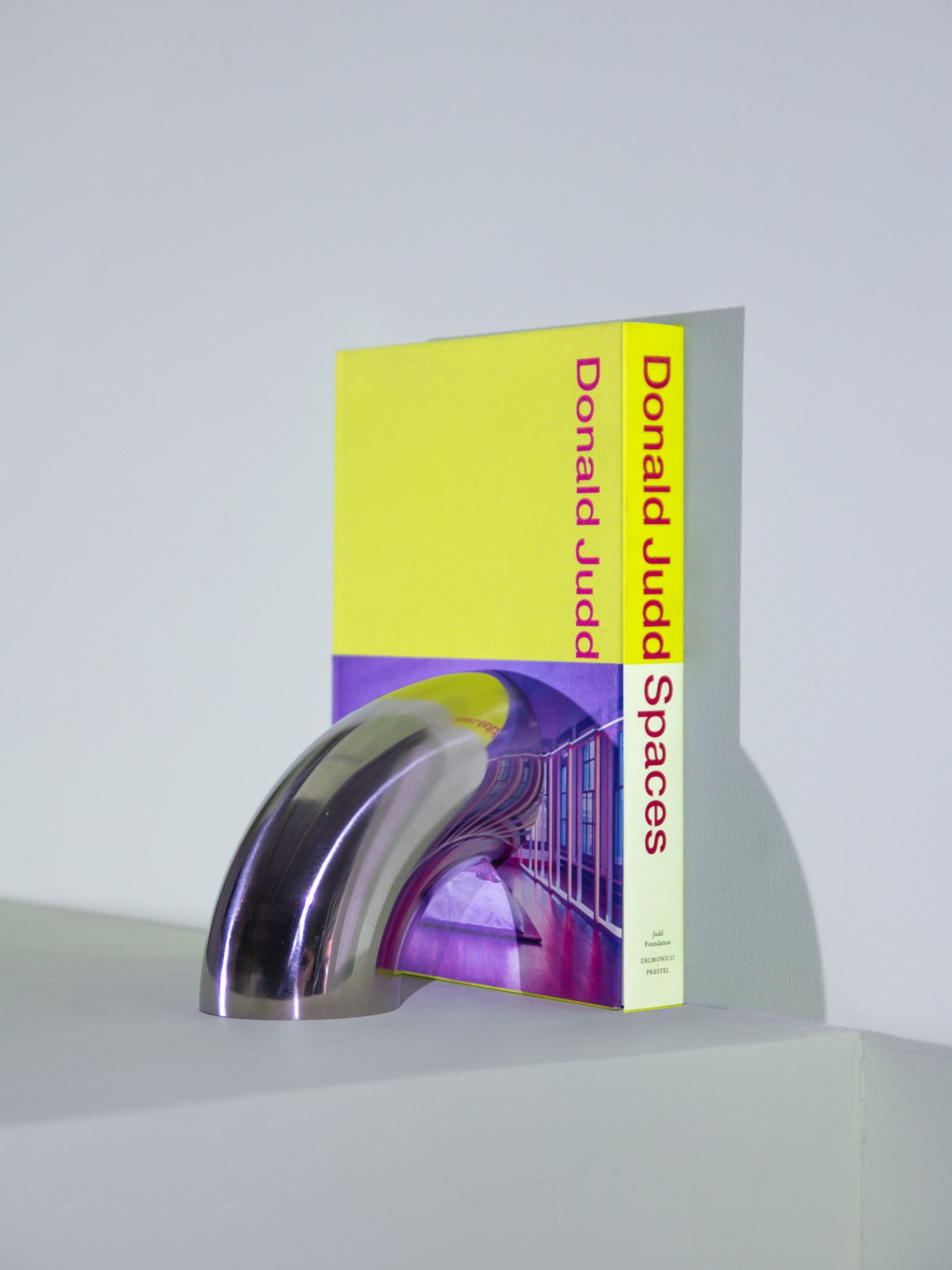

No. The Tubo bookend was my first design. And then the Capsule mirror. I was interested in a lot of high-tech design at the time, and the Tubo was the thrust of that thought process. And for the Capsule mirror, often I’ll take a less obvious element of something and expand on it. This has a 4-inch depth. And then when you put a mirror at the back of it, it becomes an 8-inch depth. It’s almost like this tunnel that you’re looking through.

How does having grown up in Oakland inform your personality and your aesthetic choices?

I grew up in Oakland in the late 90s, early 2000s. I was a runaway for a lot of my childhood. There was nothing wrong with my house or my parents, it was a very supportive household. I just wanted to go. I felt like there was something I was missing. I wanted to assert my independence. Of course, my parents were scared to death. The police sent search dogs. This was in the hills of Napa Valley at the time. That was the most remote that you could get if you lived in a city like Oakland or Berkeley.

How did you even get there?

I caught rides with friends. I don’t know if it was an aesthetic thing where I romanticized the idea of not needing to be at home. I also have an innate pursuit of adventure. And if somebody’s telling me, “No, you have to do this. You have to stay home. You’re grounded.” I’m going to do the opposite.

What was the music then?

It was Tupac. It was Aaliyah. I listened a lot to hip hop. It’s the Bay Area, so it’s in my blood.

Cat Snodgrass striking a casual pose in her Bushwick studio. Portraits by Evelyn Pustka for PIN–UP.

Cat Snodgrass, Perforated Rug, 2022; 100% New Zealand Wool.

Cat Snodgrass, Capsule mirror, 2020; ABS plastic and glass.

Cat Snodgrass, Tubo bookend, 2020; powder-coated steel.

There’s also an important ceramic culture in Northern California. I think it has a lot to do with these paths of alternative living where people in communes were creating things using natural materials.

I’m also seeing a lot of that in New York right now: studio craft, traditional processes, organic forms, bespoke design, maximalism, antiques, all this stuff is in the conversation right now.

It’s not really your style, though.

No, I love it. And I love recontextualizing it through my lens, which is more utilitarian, more industrial, more matter of fact, architectural design, extreme hyper-minimalism — whatever you want to call it. I like the two styles together a lot. I love the New York environment right now, but I also love pushing against it, to do the complete opposite.

You kind of did exactly that with Make-Do, the exhibition you designed last summer for Marta gallery in an empty building in Chinatown. It consisted of 24 chairs, and it was a beautiful marriage of crafty, vintage furniture with your very minimalist and utilitarian aesthetic. And a smoke machine for dramatic effect.

Thank you. I loved creating that contrast. There were historical pieces, and then there were the contemporary artists they commissioned under this prompt to make these ad hoc chairs within three days. I was in charge of the exhibition design, but also of organizing the space, and I remember wanting an unruly, difficult site. I was able to negotiate with the landlords of the Chinatown Medical Imaging Center in Chatham Square, a building that has been abandoned for 15 years. It was a wreck when I got it: the ceiling was falling, and there was just no way to present anything in that space unless I were to build a set within the set, like a theater stage. Between signing the lease and the day of the opening we had one week to design. It was weird. It was fun.

At which point in your career did you have a revelation of a new conception of space?

When I became interested in the Light and Space artists, I was trying to understand why those spaces have an emotional impact on me and on people in general. Robert Irwin, Larry Bell, etc. — to me these artists were engaged in this extreme exploitation of restraint. You’re reducing the thing, whether it’s sculpture or environmental, stripping it of any type of ornamentation, any type of design work per se, until you arrive at something compelling because it becomes the whole of itself. It agitates this emotional response in the viewer. It’s the space between the viewer and the physical object. It’s not the physical object. It’s not the environment nor the structure of the environment. It’s not the sculpture nor the viewer. It’s the space in between. It’s phenomenology. It’s this philosophical, poetic response to the material application or color application of light and space. Being exposed to these artists who thought deeply about these things made me realize there’s this through line between my work that I wanted to exploit. There is this thing that happens between the viewer and the physical object that isn’t easy to explain. There’s an element of the unknown.

Cat Snodgrass posing in the slipstream of Drywall Vent, a sculpture she made for the gallery International Objects in 2023. Portraits by Evelyn Pustka for PIN–UP.

Now that you’re moving more into space design, will you continue with Bi-Rite?

I am working on having Bi-Rite become self-sustaining so a team can handle it without much of my input. For now, it’s still tricky because I’m doing both at a time and it’s a lot. But that only makes me want to work harder and make it all work together. [Laughs.]

What is your dream space to design?

Maybe a church, a hardware store, or a library. And I would love to design a listening room.

And who is your dream musician to do a project with?

A lot of people come to mind: Robert Wyatt, Brian Eno, Steve Reich, Delroy Edwards, or Richard James, for example. And if he were still alive, my answer would include Lou Reed.