Speaking of poetry, Canal Street Research Association started from your curiosity towards the poetics of mistranslations on bootleg t-shirts. Can you elaborate on that?

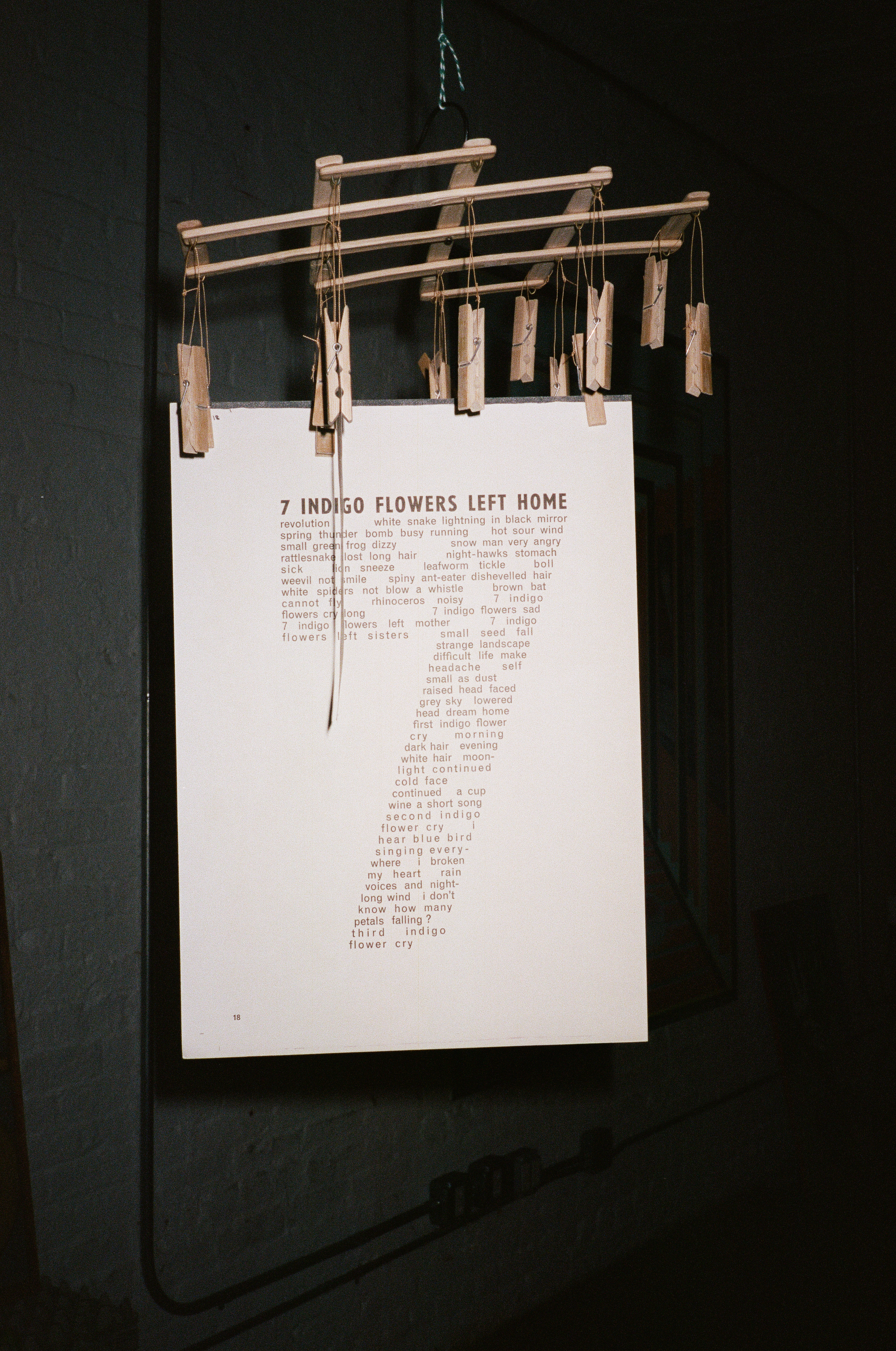

We began researching the non-standard poetic English that appears on bootleg clothing during a residency in Beijing in 2015. It was there we coined the term “shanzhai lyrics” to describe this phenomenon and to refer to our work as Shanzhai Lyric. Shanzhai is the Chinese word for counterfeit and translates as “mountain hamlet,” referring to a place on the outskirts of an empire where bandits redistribute stolen goods among those there. This concept of shanzhai, and the liberating possibilities of counterfeiting as a way to destabilize assumptions around ownership and theft, is at the heart of our project.

What have you learned about bootleg that’s specific to Canal Street?

We are fascinated by the contradictions inherent in how the counterfeits industry is criminalized as theft here. Yet the backdrop to all of this is a much larger theft of land—first by the colonizers who settled lower Manhattan and today by landlords who sit on vacant properties to falsely inflate their value.

Can you tell me about the happenings at the loft that were inspired by Canal Zone, a legendary party organized by and for artists in 1979?

Canal Zone was a legendary party held at 533 Canal in 1979, where uptown and downtown artists were invited to create a communal, sprawling work on the walls of a 5,000-square-foot warehouse. Taking its name from the Panama Canal Zone, an unincorporated U.S. territory at the time, anyone feeling lost or in-between could find themselves in this exceptional zone. Last year we started living in an empty loft, a full floor of a vacant office building that was rented to us at a special Covid rate, ten times below “market rate.” There, we were able to finally live in the neighborhood where we grew up, a dream that had long seemed unattainable. We could gaze out at the traffic on Canal Street and continue our research by talking to our neighbors. We held screenings, exhibitions, community meetings, markets, and parties.