A PERSONAL TRIBUTE TO THE LATE ZAHA HADID

In the early hours of March 31, 2016, we lost Zaha. I’m speaking familiarly and collectively because the body that died under aseptic sheets in a Miami hospital was that of a myth. There’s so much in a name, and her singular, breathy four-letter stamp, streamlined by the swagger of the last, quizzical letter of the alphabet (not her native one), was already the translation of an individual, born in a certain time and place, towards a global phenomenon.

Everyone called her Zaha, and she tended to address the people she really appreciated with a label of her own confection — “Potato,” “Dumb-Dumb,” “Wiggles.” She could lob nicknames like cotton candy into particularly thorny situations — over an intercom system or across an auditorium, whipping the mood to a sugary high. I desperately awaited my treat. I’d stockpile her text messages (the state of a competition entry, the weather, holiday plans in Casablanca) like coded slips from an imaginary courtship in which I played the role of an oafish adolescent. She could respond at any hour, not so much from insomnia, or because she might cross multiple time zones on any given day, but because she mastered the art of contact, of keeping her world close. She used several phones. They might be arrayed on any given table, in any given hotel, restaurant, conference room, like chess pieces in a very large game. I imagine the hundreds of thousands of texts bleeping in, all brusquely, coyly, and caringly responded to.

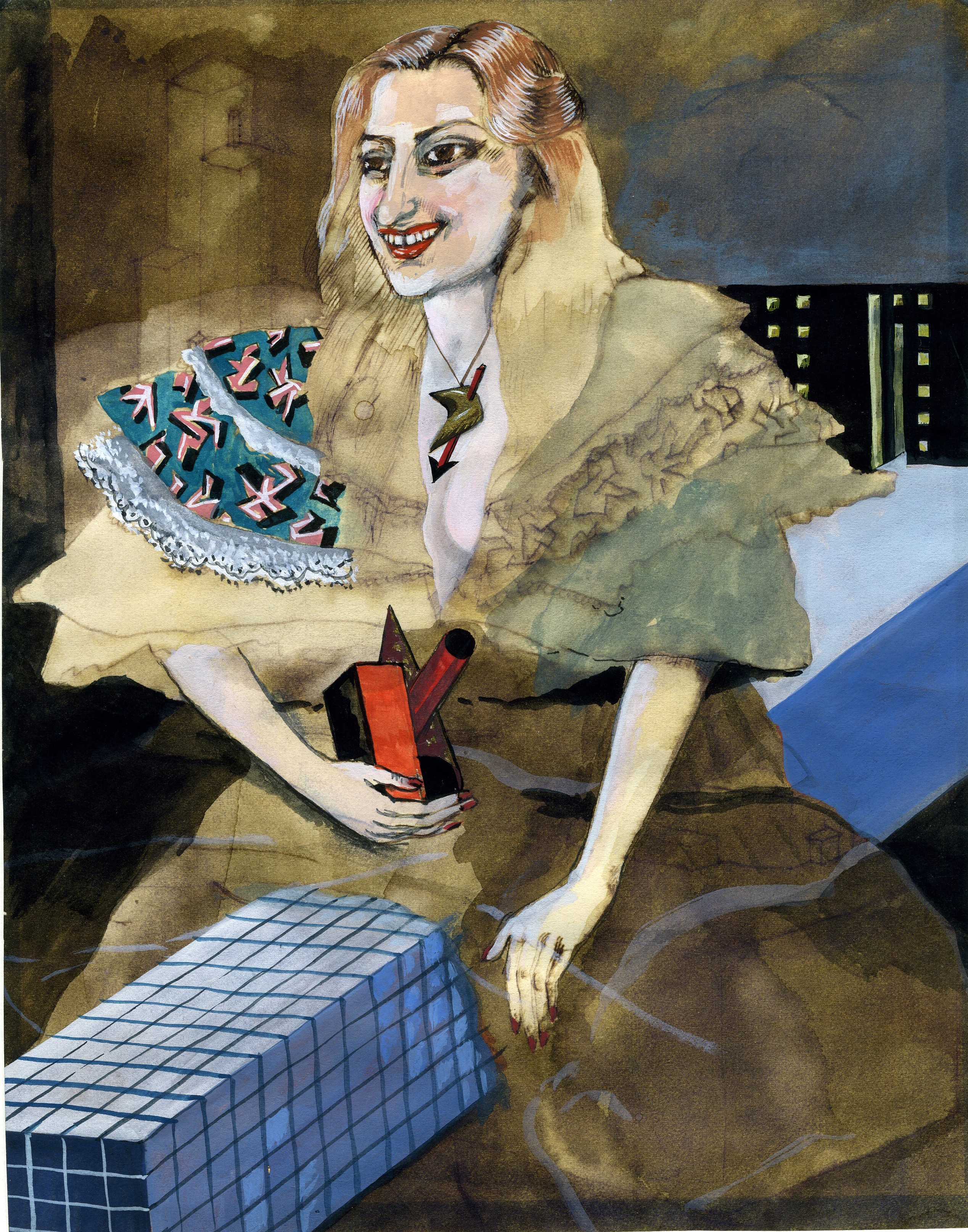

At 10 Bowling Green Lane — her London office and design studio located in a Victorian schoolhouse — she would appear in the early afternoons to consult with her project managers. It was something of a ritual, and repeats itself in my mind just as I saw it one summer. Zaha wore a silk sheath dress of opalescent yellow, a sunset over Cairo, or a poorly mixed glass of pastis. Ahead of her came Fracas — a word that English can happily translate as “public disturbance” — a perfume by Robert Piguet of jasmine and gardenia, white iris, sandalwood, and musk. It almost always wafted — humid, gaseous like jet fuel — in her absence. You knew when Zaha was in the room. Sitting at a sky-lit desk, she quietly water-colored and sketched to the hushed tones of one or another hovering informer. It was the executive office in the boudoir, governance by tête-à-tête. Some days, the back seat of her chauffeured car would second as the conference table, the motor running.

At times she could be dismissive even churlish — she was, after all, a head of state, managing a tightly wound, working village of 400 as well as small, provisional satellites at key project sites in Rome, Beijing, New York, or wherever. But she returned the loyalty she exacted, and her ways of caring too were many, various, and surprising. It may have been a hot, unusually sunny summer in London when I first met her, when she was made a CBE and shared the queen’s celebration cake with the staff, and ordered ice-cream pops for anyone in the office, but these were all decoys of sorts. I had never before seen an office set free to dream, disabused of professionalisms, in quite the same way, as if the ground plane there had been purposefully set at 89 degrees (the subtitle of one of her early paintings), a small, catalytic disturbance that shifted everything into gear. “We can no longer fulfill our obligations as architects if we carry on as cake decorators. Our role is far greater than that,” she wrote in 1983. She could be sweet, but never saccharine, because architecture was simply too vital an operation in the world. It was in the living, collaborative ground at 10 Bowling Green Lane that I witnessed how architecture could change people.

We lost Zaha, and I lost something of a raison d’être, some undeniable license to think architecture, to project the discipline, differently. I mean this in ways far beyond the practice of design. Well before she died, however, we lost her — a cult of personality, a great female architect, first woman winner of the Pritzker Prize, one of the boys, but a reject from the club, an entrepreneur, a detached opportunist, an architect in fashion, a fashionista, a starchitect, a visionary, a pure formalist, an outsider, an avant-gardist, a privileged child, an Arab in the West, a gift of orientalism — the monikers have piled up, all in some way misplaced. We misplaced Zaha from the start, and in that sense we lost her too soon.

To borrow from Colin Rowe and Fred Koetter, who, when writing Collage City, borrowed from Isaiah Berlin, Zaha was a fox dressed like a hedgehog (something like Le Corbusier and not like Mies their argument goes), a fierce, multifaceted, strident polymath who we tended to reduce to one or two simplistic notions. She would buy up matryoshka dolls from the flea markets in Beijing, she once told me over dinner. The dolls were painted with the faces of politicians — I imagine Reagan nestling into Yeltsin, as harmoniously as their names chime. As she recounted her story, I could sense some delicate pleasure emanating from her (all the more intimidating since it was just Zaha and me, our tête-à-tête) in the action of twisting off a politician’s head, heading off the status quo, as it were, revealing how it’s all so monstrously embedded. She was once asked to put out her cigarette (back when she smoked) at Harvard’s GSD. She refused. “I’ll stop smoking when you stop bombing Iraq,” she retorted. There’s so much in that one line, so much we still need to understand about the word “Zaha.” Pundits, journalists, hagiographers, and historians have nearly all been fooled by the decoys of their own making. Her legacy has yet to be unraveled and, I know, will prove more tumultuous than anyone imagines. Zaha is my patron saint of misfits and marvels, a queer architect, a maker of queer spaces in all the ecstatic, complicated, socially liberating ways that term promises. I found something of myself there, with her.

Taken from PIN–UP No. 21, Fall Winter 2016/17.