The Teflon skin of the Greenwich Millennium Dome. Photo by Grant Smith. Courtesy of RSHP.

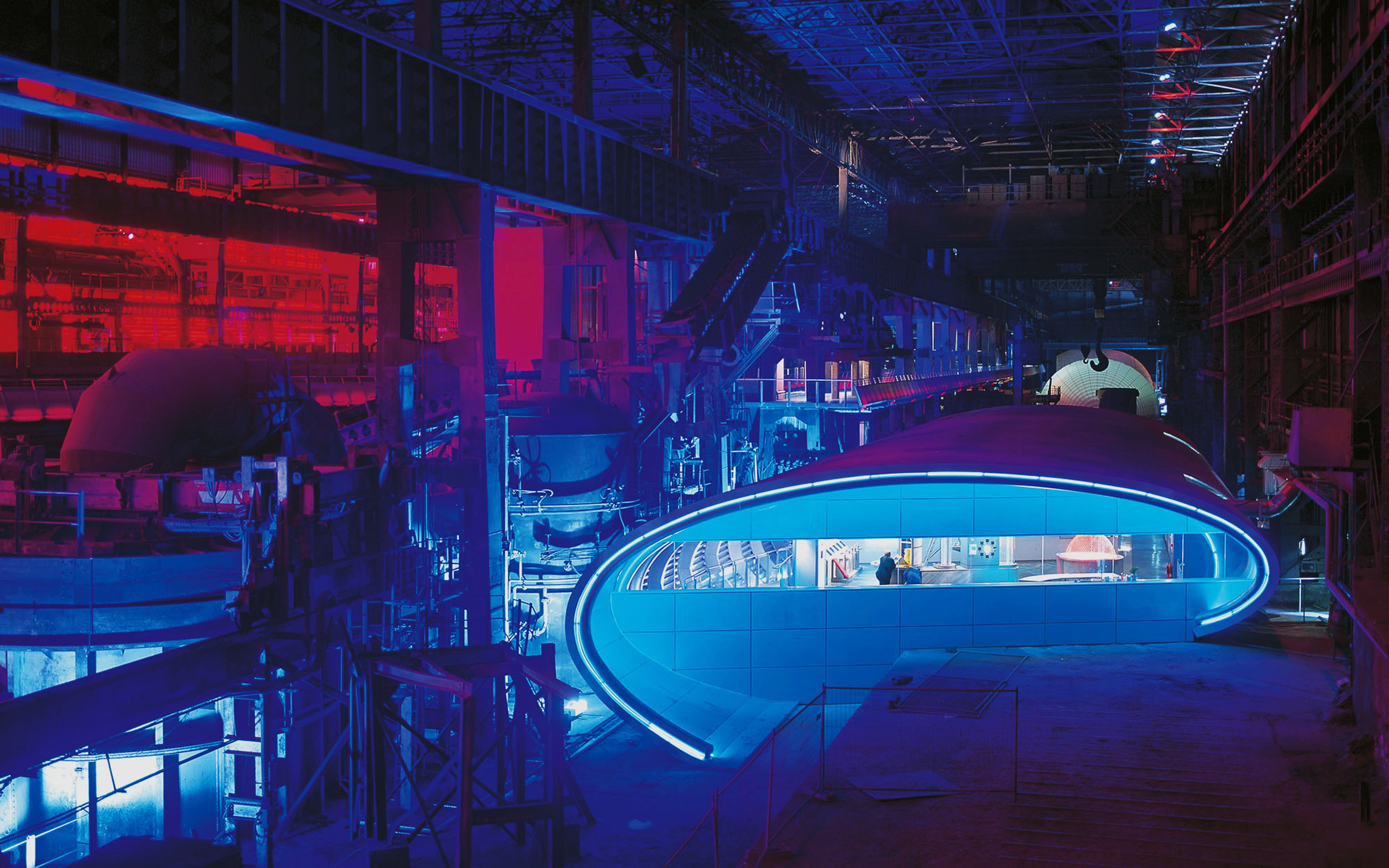

Magna Science Adventure Centre (2001). Rotherham, UK. Wilkinson Eyre Architects.

On December 31, 1999, London’s Millennium Dome was inaugurated with an extravagant opening ceremony attended by Queen Elizabeth II, Tony Blair, and a range of celebrity guests. Earlier that year, Pierce Brosnan dropped from an exploding hot air balloon onto its tensile fiberglass roof in the opening sequence of the latest James Bond film, The World Is Not Enough, and promotional material referred to the structure as the “first wonder of the new millennium.” In the late 1990s, Britain was undoubtedly having her moment; the Spice Girls, Manchester United, and other cultural exports, from music to fashion and nightlife, were all symptoms of what quickly became known as “Cool Britannia,” a phenomenon that spread from pop culture to politics. As such, it’s easy to see the Millennium Dome as the natural architectural extension of this mania — the Posh and Becks of the built environment, so to speak.

Unveiling plans for the Dome’s Millennium Experience exhibition in 1998, Blair stated: “This is Britain’s opportunity to greet the world with a celebration that is so bold, so beautiful, so inspiring that it embodies at once the spirit of confidence and adventure in Britain and the spirit of the future in the world.” This outward-looking, chic sense of nationalism is hard to grapple with from the perspective of a deeply conservative and divided country now under the shadow of Brexit, but it helps to suspend disbelief for a moment and imagine a time before Britain became ashamed of itself.

Inside the Millennium Dome. Photo by Paul Pope.

The Dome was just one of 190 landmark public architectural projects financed by the Millennium Commission, an independent public body set up in 1993 dedicated to distributing money raised through the National Lottery to various initiatives across the UK. The tremendous scale of the scheme covered the planting of community woodlands and restoration of village halls in rural areas, to large-scale urban regeneration projects and the establishment of museums of national significance. After more than a decade of Thatcherite neglect, cities and towns across the country scrambled to emulate their own version of the “Bilbao effect” following the major rejuvenation of the Basque city that came with Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim outpost in 1997. Many of the recipients of Millennium Commission funding were indeed new cultural institutions, including Herzog & de Meuron’s Tate Modern in London (£50 million grant), Stirling & Wilford’s The Lowry in Salford (£15.65 million grant), and Simpson Haugh’s Urbis Exhibition Centre in Manchester (£20 million grant), to name a few.

Millennium Dome central show - acrobats on structures. Photo by VasuVR.

While it’s hard to discern a singular aesthetic style of the millennium projects given their sheer number, many share common characteristics that might be expected of Y2K architecture, conceived in the early days of architectural 3D modeling software. The twin Millennium Bridges in London and Gateshead, the Millennium Dome, and to some extent, the Spinnaker Tower in Portsmouth are characterized by grand expressions of structural engineering, rendered in white-painted steel. New technologies and materials also made it possible for ‘paper architects’ to finally imagine their utopian creations in the real world, such as the cluster of ETFE biospheres creeping their way across a Cornish Hillside that make up The Eden Project, or the similarly-clad translucent rocket tower of the National Space Centre in Leicester. While it would be easy to accuse this kind of materialization of feeling dated today, its legacy surprisingly lives on, with a similar surface approach taken as recently as Diller Scofido + Renfro’s The Shed at Hudson Yards.

The Teflon skin of the Greenwich Millennium Dome. Photo by Grant Smith. Courtesy of RSHP.

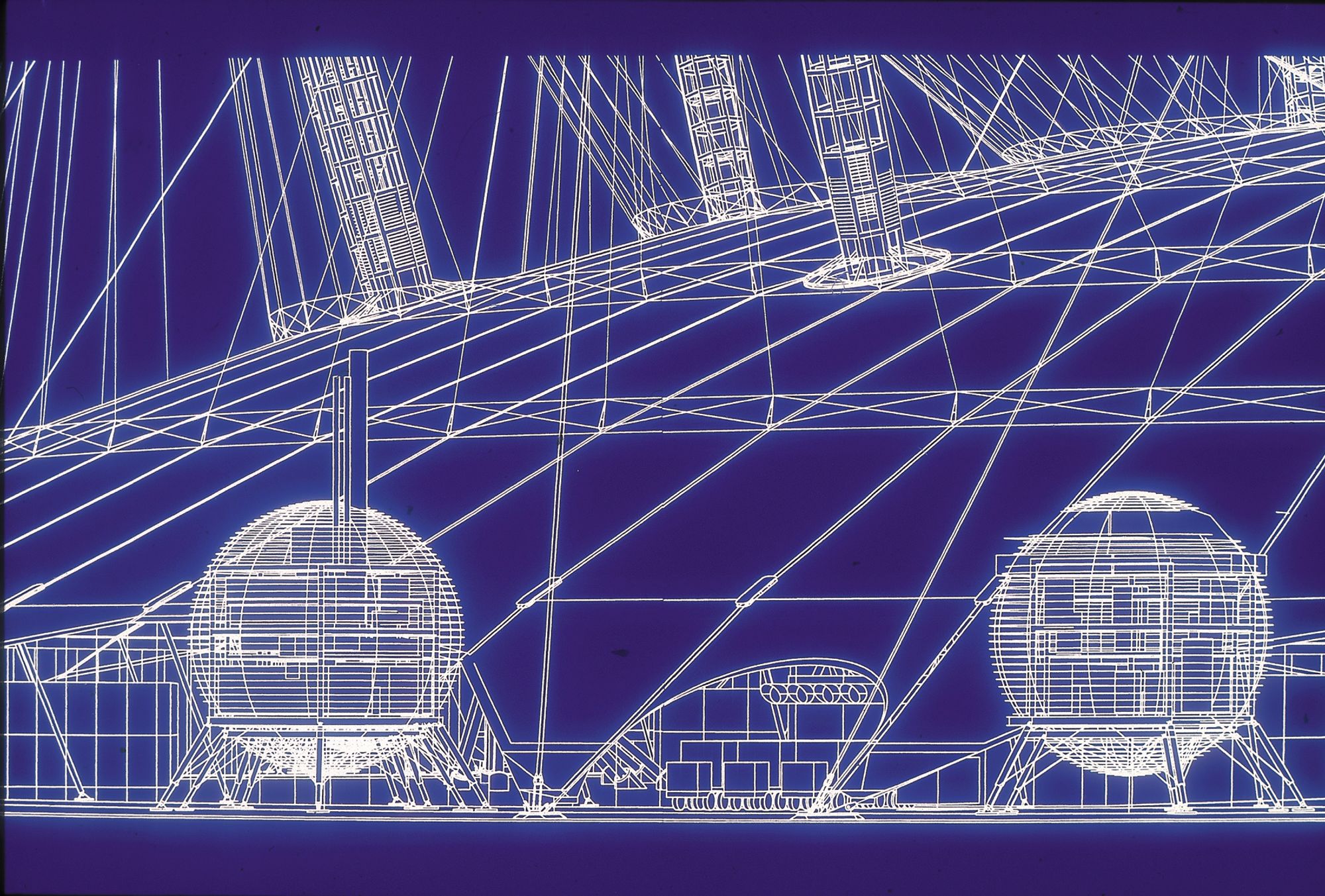

Detail of an early Millennium Dome blueprint showing circular service towers. Courtesy of RSHP.

While many projects channeled the trends of the new millennium, a number of others took a more sensitive approach to adaptive reuse of existing structures. Since Britain’s economy had been violently deindustrialized under Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s, the 90s left a wake of abandoned buildings and brownfield sites waiting to be repurposed for the burgeoning experience economy. Most famously, Herzog & de Meuron inserted ramped access into the cathedral-like turbine hall of London’s Art Deco Bankside Power Station, quickly becoming a spectacular exhibition space in the internationally renowned Tate Modern. Outside of London, WilkinsonEyre’s Stirling Prize-winning Magna Science Adventure Centre in Rotherham, South Yorkshire slotted pavilions inside a cavernous former steel mill. Inspired by the four elements, floating structures suspended by steel cables and industrial catwalks were illuminated by a dramatic neon lighting scheme that could have been equally at home in a nightclub. With a twist of postindustrial irony, an hourly indoor pyrotechnic show mimicked the steelmaking processes that had long since been outsourced to other parts of the world.

The Millennium Commission was truly ambitious in the kinds of projects that it funded, but government procurement policy at the time meant even the most generous public funding had its limits. The Private Finance Initiative (PFI) scheme, first initiated by former Prime Minister John Major before being significantly expanded under Blair, mandated that public contracts must go out for tender to private companies. Architecturally speaking, PFIs often led to value-engineered shortcuts in the final detailing, construction, and maintenance of a building. This aggressively neoliberal policy was highly contentious when first championed by a Labour government, signaling a wider shift in the party’s direction away from its Socialist roots. (It’s telling that years after her time in office, Margaret Thatcher famously claimed that her greatest achievement had been “Tony Blair and New Labour. We forced our opponents to change their minds.”)

View of the Millennium Dome during open week. Photo by Paul Pope.

Millennium Dome. Photo by Paul Pope.

By the turn of the Millennium, architecture had become a significant tool for New Labour to showcase their flagship ideology. Although the Millennium Dome received more than £500 million of public funding, being a pet project of the government necessitated showcasing a newfound openness to private investment. The structure’s 14 exhibition areas surrounding its central performance space were designed by different architects and artists, each funded by an array of corporate entities. Pharmaceutical retailer Boots sponsored the dazzlingly pixelated Nigel Coates-designed Body section together with L’Oréal, and in what might be seen as a grotesque foreshadowing of the illegal invasion of Iraq that would define Blair’s second term in power, Zaha Hadid’s elegantly cantilevered Mind Zone was sponsored by multinational arms company, BAE Systems.

Body Zone exhibition at the Millennium Dome (2001) London, UK. Nigel Coates.

In spite of the initial flood of funding around the millennium projects — or perhaps because of it — many turned out to be a flop. The Dome quickly fell out of favor with the media, framed as a vanity project of New Labour. When the Millennium Experience exhibition closed for good after just one year, the largest non-industrial building in the world sat empty for five years amidst desperate attempts to find a permanent occupant until finally being converted into the now successful O2 arena. In Manchester, a £42 million cultural attraction built in the wake of the 1996 IRA bombing of the city center, designed with the vague intention to “explore people’s experience of the modern city,” was leased to the more contextually relevant National Football Museum in 2010. Unfortunately, not all projects were lucky enough to reinvent themselves. Big Idea, a £14 million museum of Scottish inventions in Ayrshire, closed after just three years due to declining visitor numbers after a similar science museum — also funded by the Millennium Commission — opened in nearby Glasgow. The building has sat completely abandoned since, and the swinging pedestrian bridge built to connect it across the River Irvine has been left permanently open, severing the museum from the mainland. In Bristol, an IMAX cinema and indoor rainforest experience known as Wildwalk At-Bristol closed for good in 2007, with the managers citing the end of certain grant schemes they had been a beneficiary of had come to an end, as the government had reduced funding for science museums in England.

It’s a sad reality that the funding used to support the construction of some groundbreaking public institutions was not sustained to cover their maintenance over time, which raises important questions over the hubris of the scheme in the first place. As soon as the Conservative government took power in 2010, funding to local authorities was cut even more dramatically. Its severe austerity measures are still felt today — several cities including Birmingham, Nottingham and Croydon have gone bankrupt. It’s therefore increasingly rare for an architect to get a commission for a new major public building in the UK at all, especially outside of London.

Cover of The Architectural Review, April 2000.

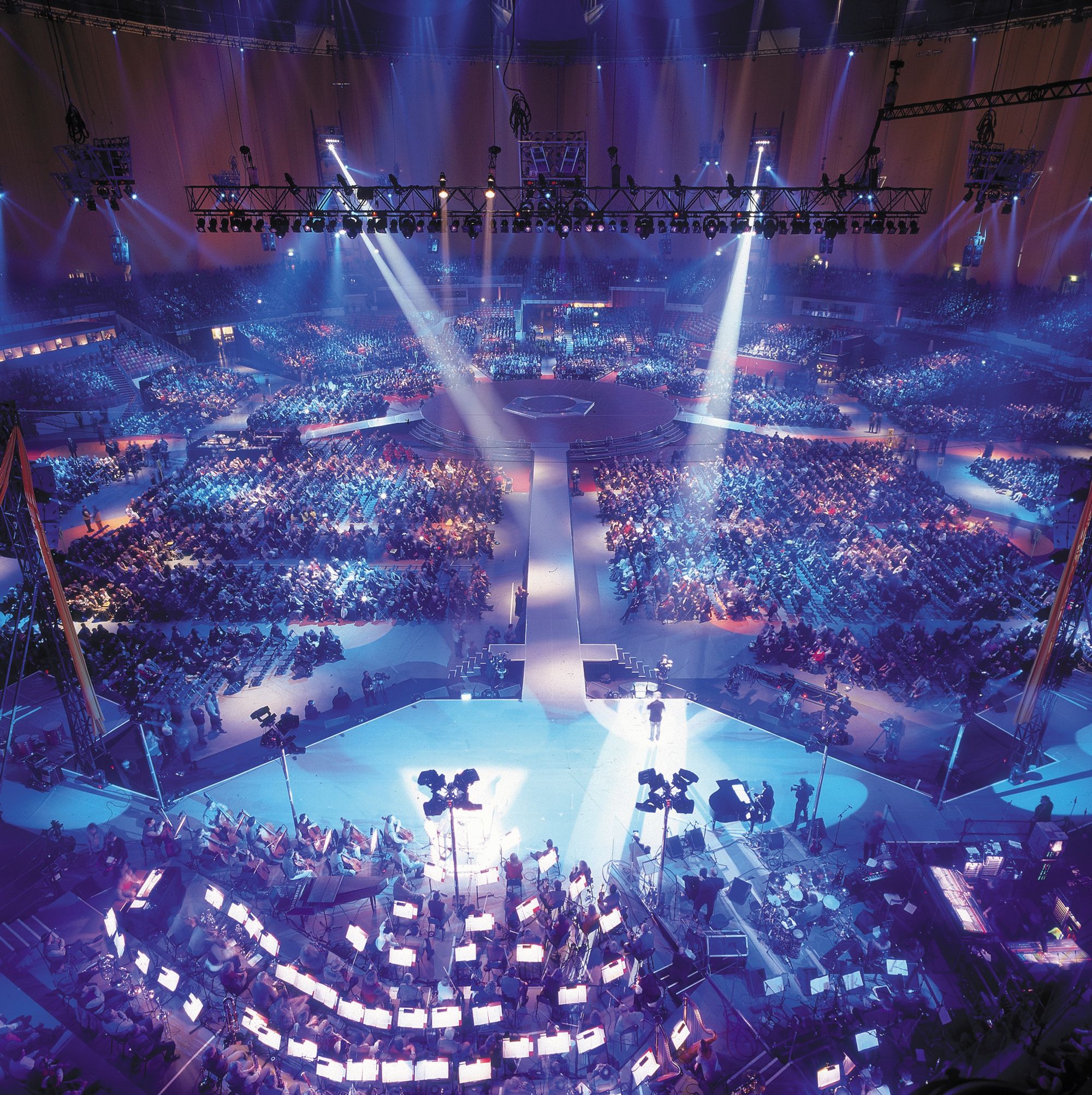

View of the Millennium Dome's central performance space on the opening night, 31 December 1999. Photo by Christian Richters. Courtesy of RSHP.

Architecture has always served as a reflection of the political and economic climate within which it is conceived — not so much in terms of aesthetic sensibilities, but often in the kinds of buildings being constructed in the first place. To compare the Tate Modern (arguably the most successful of the millennium projects, conceived at the height of anticipatory Y2K enthusiasm) to its sister power station of Battersea, renovated just 22 years later, one was transformed into a free-to-enter world-class art institution, the other as an “iconic retail and leisure destination” surrounded by an awkward cluster of competing luxury apartment blocks.

As easy as it is to malign the millennium projects and New Labour for their failures, one can only dream of such ambitious publicly funded cultural institutions opening in Britain today. In the past few months alone, the OMA-designed Aviva Studios (formerly Factory International) in Manchester had to sacrifice its own naming rights to a multinational insurance company to cover a funding shortfall, and the British Museum just signed a controversial £50 million partnership with BP to fund vital maintenance to its building, amidst calls for cultural institutions to divest from fossil industries.

The Millennium Dome (2000). Photo by Martin Pettitt.

Having first moved to the UK from Canada as a kid in the late 1990s, I have fond memories of visits to various newly opened rubber-floored science centers, aquariums, biospheres, and bridges on school field trips or with my family, each sparking an early curiosity for architecture. In the years of austerity since, it’s increasingly difficult to imagine a young person having that same experience today. While many of the original millennium projects do still exist, the sense of optimism that characterized Britain at the time that they were built has long worn off. To visit these buildings today opens a portal into a seemingly different country, where both civic pride and internationalism could coexist. It’s hard not to be nostalgic for that small window in time when architecture was seen as important to the country’s future — back when Britain was still cool.