BORDER CROSSING: THE EXCHANGE OF ARCHITECTURAL IDEAS BETWEEN CALIFORNIA AND MEXICO

Tucked away at the far southern edge of Mexico City, the neighborhood of Jardines del Pedregal sits atop a rocky plain formed by the cooled ancient lava that once flowed from the nearby Xitle volcano. Today, some of the most luxurious mansions in the city pepper the landscape, making Pedregal, with its trimmed gardens and meandering roads, an oddly enchanting residential dreamscape. Now a popular Airbnb destination, the site was originally the brainchild of celebrated modern architects Luis Barragán and Francisco Artigas and tells a silent tale of the region’s torrid affair with modern architecture.

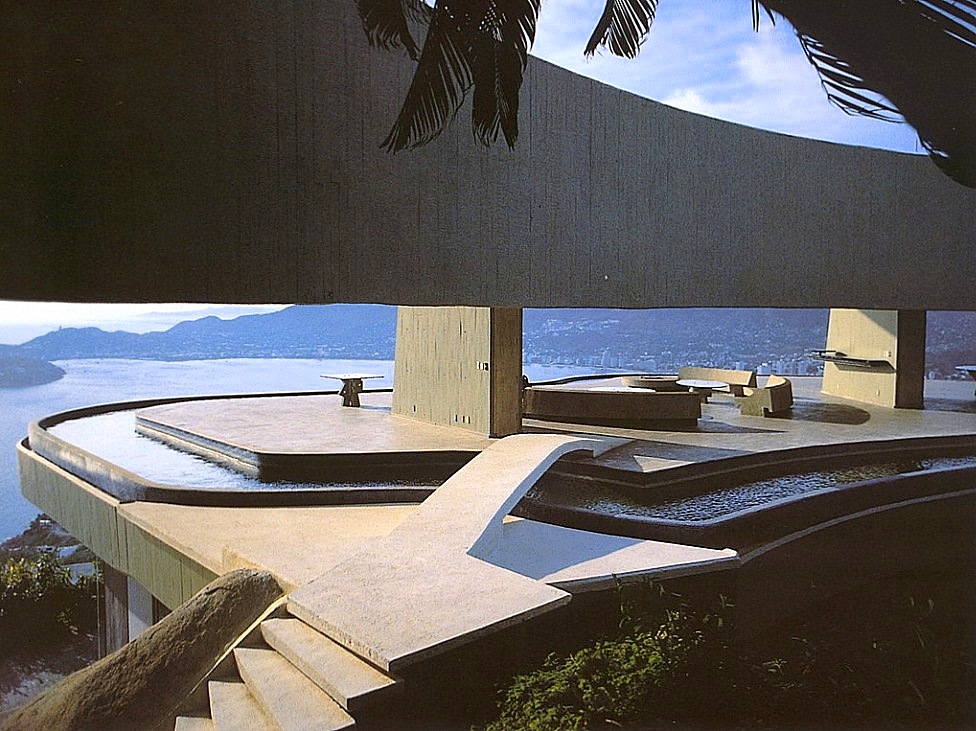

John Lautner’s Casa Marbrisa, Acapulco, 1973. Photo by Jan-Richard Kikkert.

Although most of the elaborate residences are recent constructions, the original designs carried classic markers of a distinctly Californian interpretation of the International Style. But this isn’t all that surprising. As the exhibition Found in Translation: Design in California and Mexico, 1915–1985 at LACMA demonstrates, the Golden State has strongly influenced Mexican architecture for over a century, beginning with the the rapid spread of Spanish Colonial Revival that still marks the typical Californian suburb with its white stucco exteriors and orange clay roofs — a contrived romanticization of the rustic colonial missions of New Spain that the U.S. projected back onto Mexico, for it spoke to the dream of American luxury — “dreams money can buy,” in the words of critic Reyner Banham.

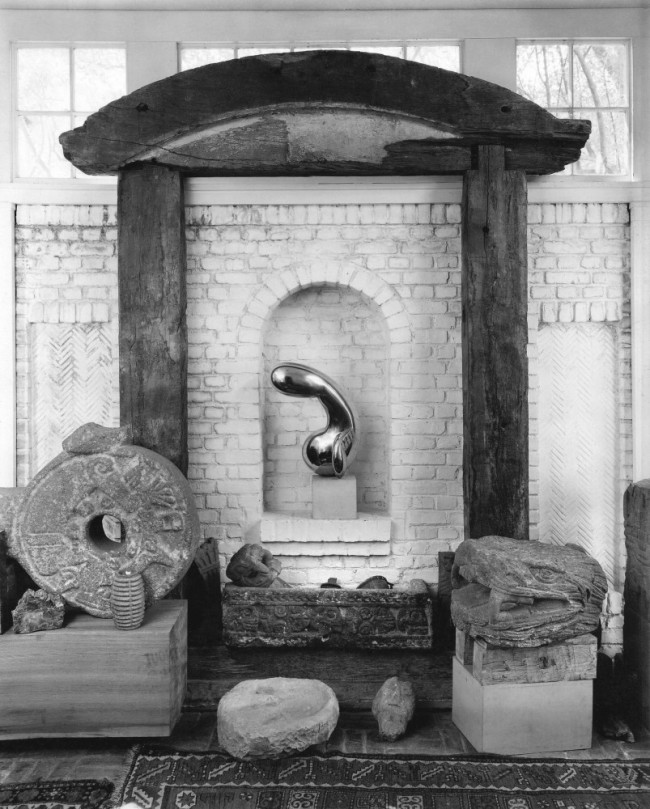

Francisco Artigas’s Fernández House in Gardens of El Pedregal, Mexico City, 1957. Photo by Roberto Luna.

But the architectural tryst between California and Mexico during the early stages of modernism is more complex, though ever-rooted in dreams. Before Richard Neutra even set foot in California, where he undertook the majority of his delicate, rectilinear work, he dreamed of Mexico — “a place of wonder” he once remarked. Bewitched by his own fantasies, Neutra traveled to the country just months after relocating to the States from Europe. There, he encountered the regional modernism of Barragán and Juan O’Gorman, architects who developed a style of their own through the merging of European functionalism and a Mexican symbolism steeped in references to indigenous culture and the surrounding southwestern landscape.

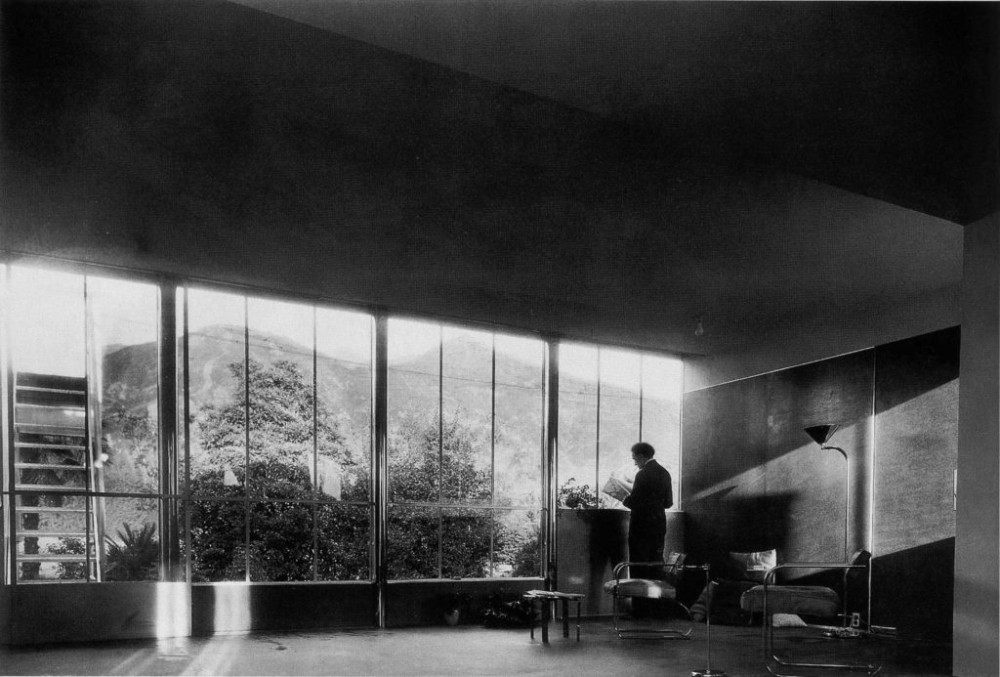

Richard Neutra, Beard House, Pasadena, California, 1934. Photographer unknown.

Richard Neutra, Beard House Interior, Pasadena, California, 1934. Photographer unknown.

Neutra transferred this regional modernism back to California to soften the rigid austerity of his earlier work. His 1934 Beard House gestures at the interior patios seen at the Mayan Nunnery in Uxmal that are now so typical of Mexican homes. But the artistic exchange went both ways — fellow émigré Max Cetto would later carry Neutra’s interpretations from Mexico back over the border once again in his plans for Pedregal. And in 1937, the San Francisco architecture duo Ernest and Esther Born published The New Architecture in Mexico after being mesmerized by their tour of Mexico City by Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in which they claimed, “We had thought of our neighbors as engaged in pursuits different than ours,” only to find out that “they are engaged in the same pursuit… the point of view is familiar but the accent is different.”

Detail of Mayan Theater Façade by Stiles O. Celements, 1927.

This revelation, however, gave way to new cultural contortions. Consider the nostalgia for Mayan structures in the modernism of Frank Lloyd Wright — whose blithely-branded American style reduces indigenous Mexico to an aestheticized pastiche — or the Art Deco corruption of pre-Columbian design in the Aztec Hotel of Monrovia or The Mayan Theater in Los Angeles (which is now a nightclub). California couldn’t help but continue dreaming of exotic folklore. But architects on either side of the border were complicit in myth-making. Mexican publications like Arquitectura/México and Espacios glorified Neutra’s more European work for its egalitarian undertones, while Californian architects like Cliff May took cues from the open plan of Mexican haciendas. But amidst these false fantasies, Pedregal, despite its changes, remains a testament to the design exchanges between Californian and Mexican architects, showcasing the former’s endurance against an aesthetic of universalism, and the unique sense of regionalism that can be born from competing cultural imaginaries.

Text by Arshy Azizi.

Found in Translation: Design in California and Mexico, 1915–1985 is on view at LACMA through April 1, 2018.