CHARLOTTE’S DARK WEB

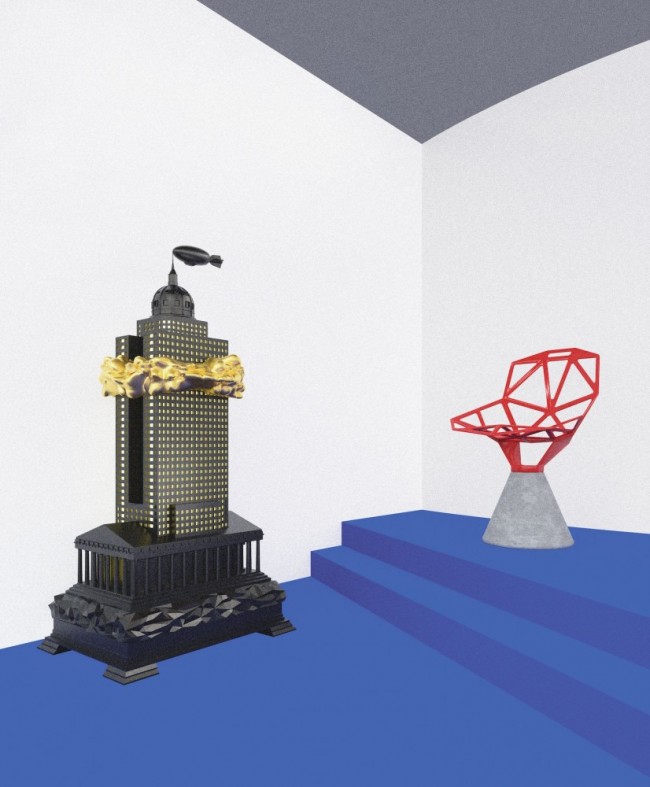

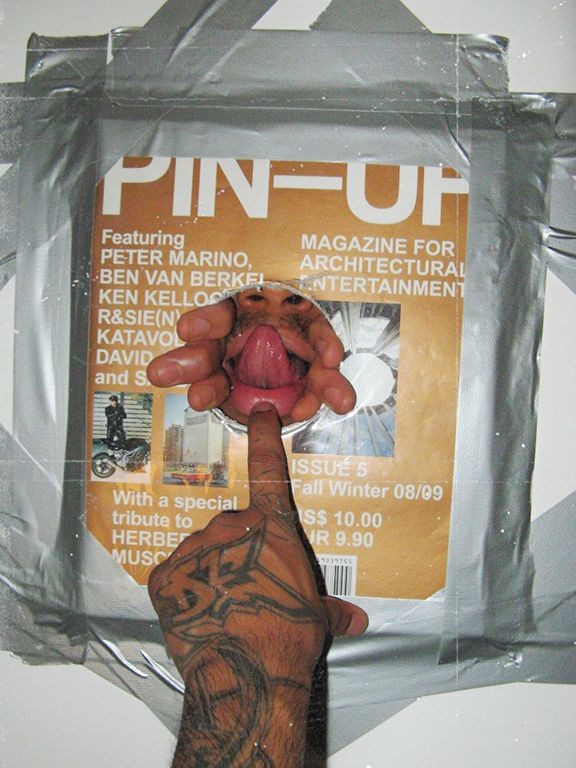

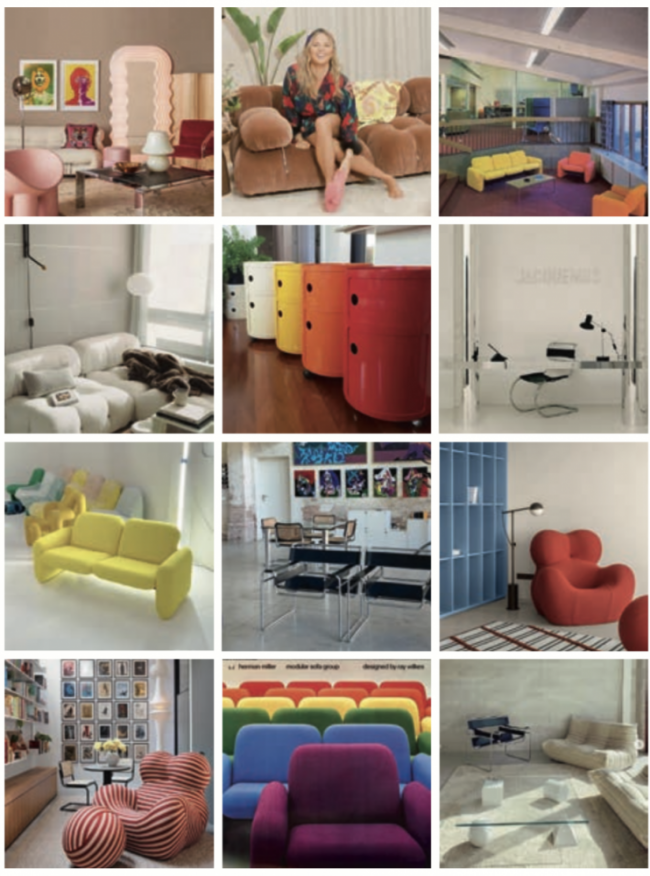

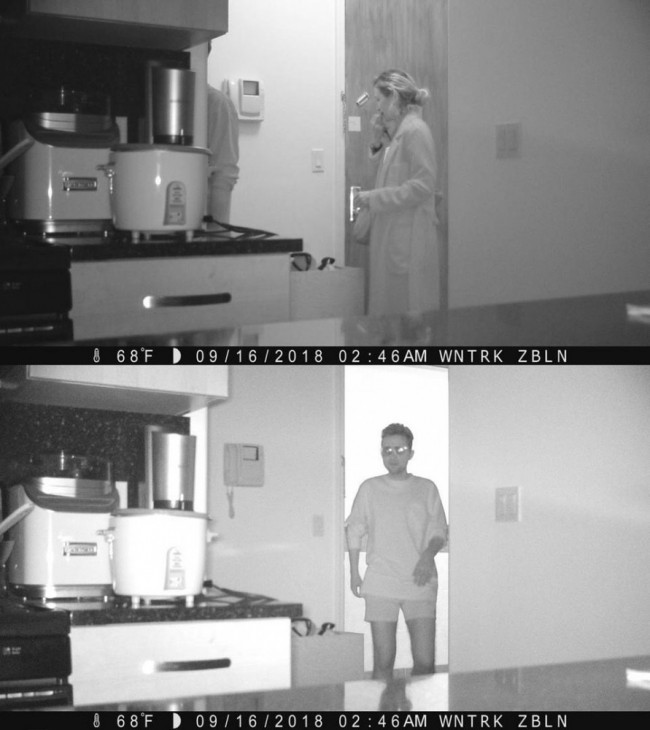

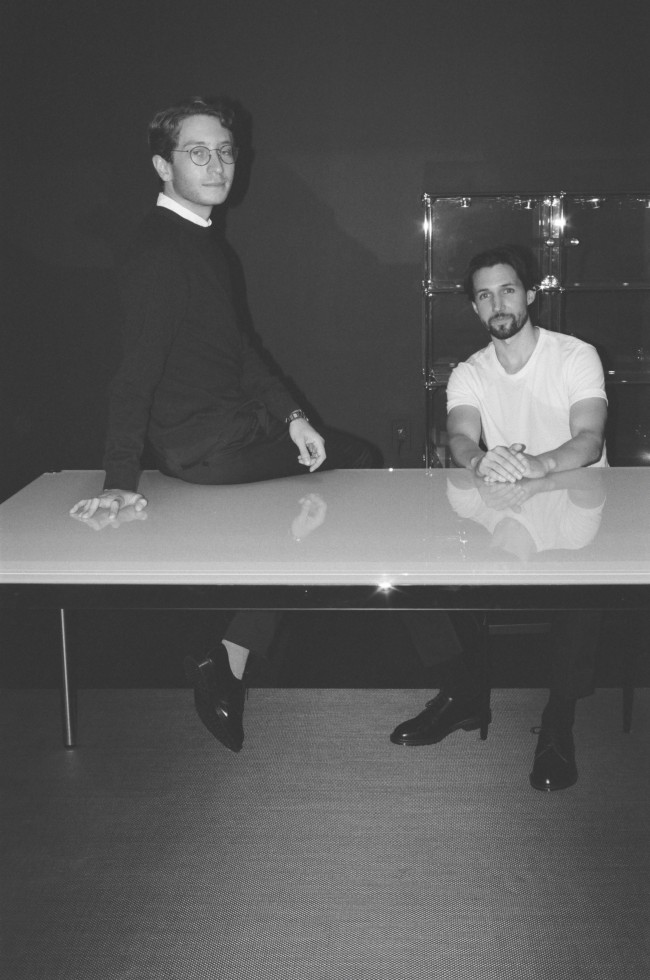

The exhibition Blow Up curated by Felix Burrichter and designed by Charlap Hyman & Herrero and currently on view at Friedman Benda gallery New York, is an exploration on design, scale, and the conditioning of childhood. As part of the exhibition program, we asked five writers to write a special diary entry around the theme of childhood, design, and their ideas of domesticity.

There probably was an alternate universe where I was not sick. I thought about that place. I was tired of being here, alive, destroyed, decorating a dead tree. That used to be fun once, just like how I used to be. But I’d changed. That’s what routine can do to you. Make you unlike yourself. I’d accepted this. Felt stuck to it.

I had decided to buy drugs after googling how to tie a noose. I wasn’t afraid of losing my mind, I was afraid of losing my life. Thought drugs might save me.

I went online. I wasn’t dumb. I knew how to get things. My marriage had been a way to escape my psycho parents. Someone I asked told me about a drug in the form of an oil. She said, how much do you want? I said, a year. The package came stamped with a blue spider, the symbol, I guessed, for high-quality stuff.

Before I got high, I sobbed. This was usual. I was always somewhere in my house crying. My sons were in the living room watching something. I thought to myself, I should at least look like I’m working. I barely dusted, looked around, got the drug from where I’d hid it, took two drops as instructed, and waited.

After ninety minutes, I looked outside. The trees were breathing. Their leaves were a dark red, like the shade of a dress I’d once bought and never worn. The wind shook and tossed them. Nature was wild and good. Where was that dress? It had been years. The trees were probably a hundred years old. Somewhere I’d read that they rot in the middle before they go, as if a cavity got in its heart.

-

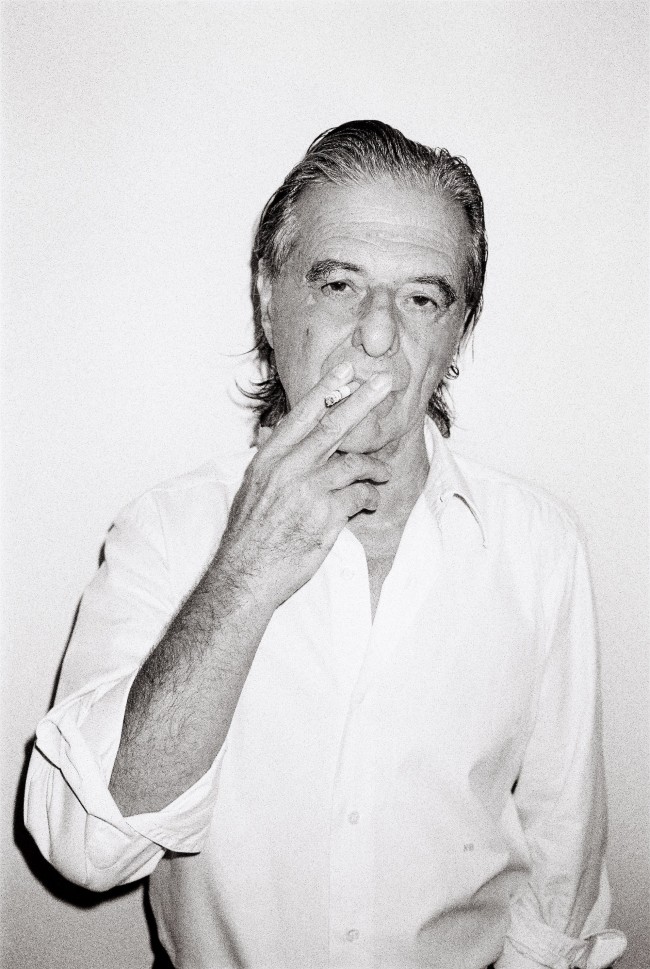

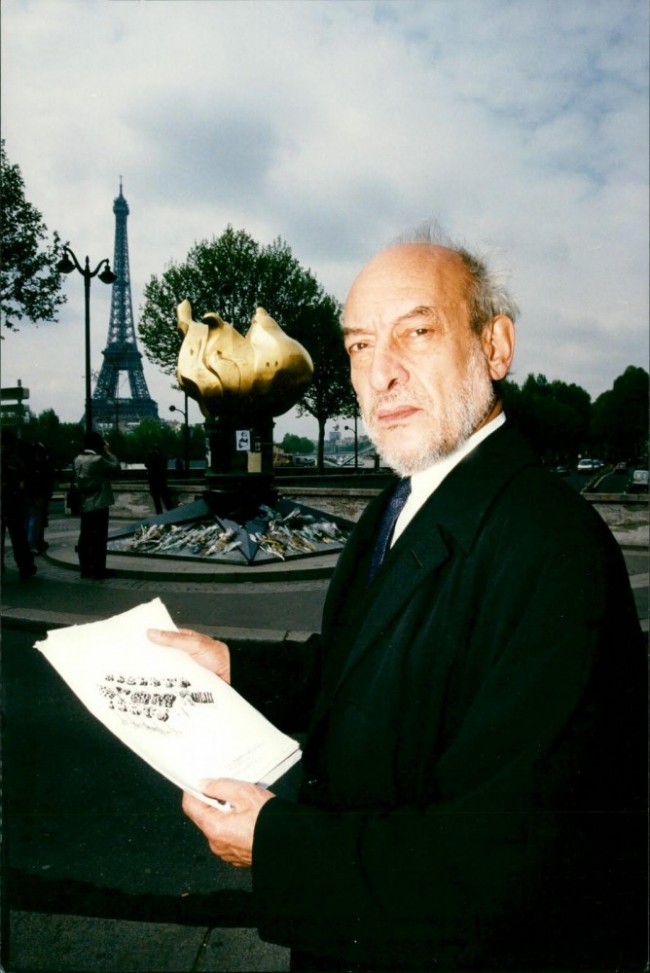

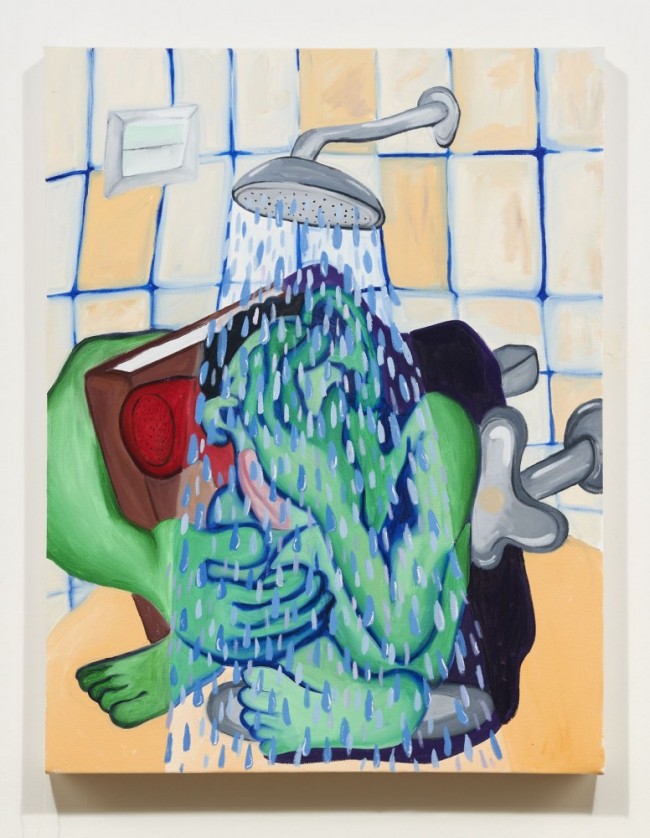

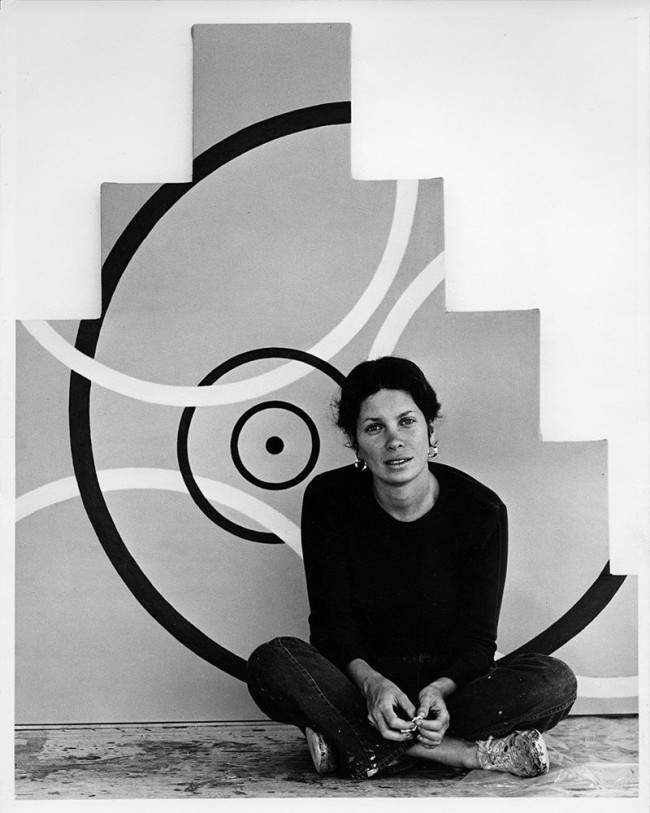

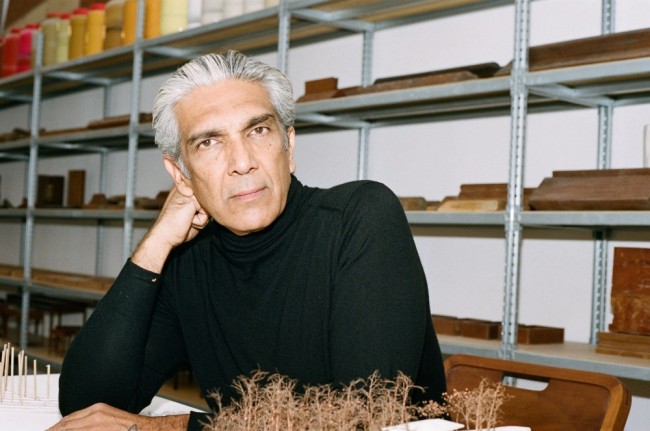

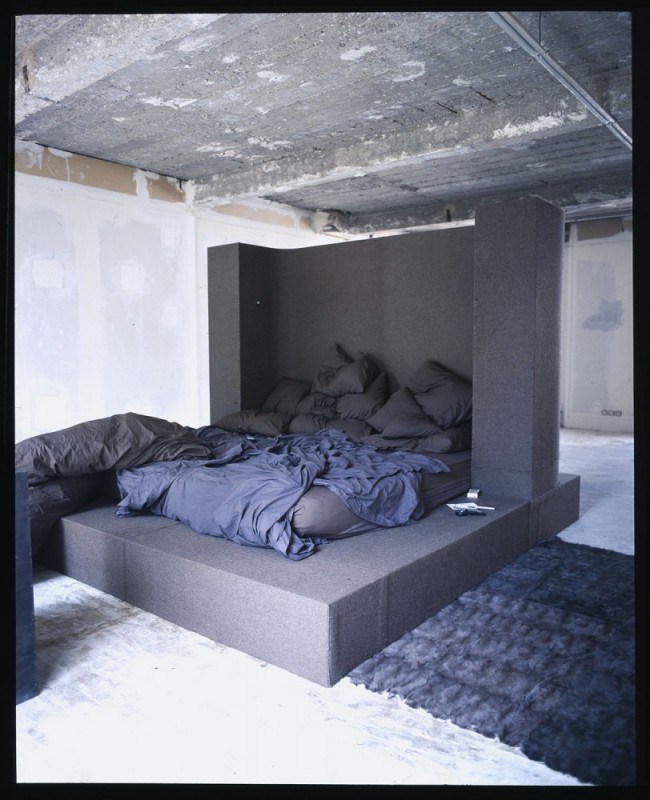

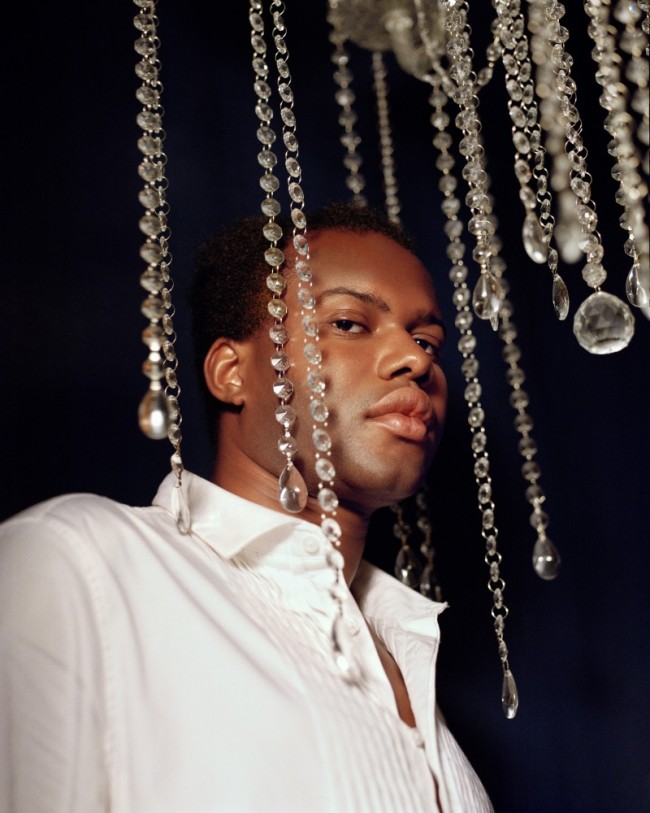

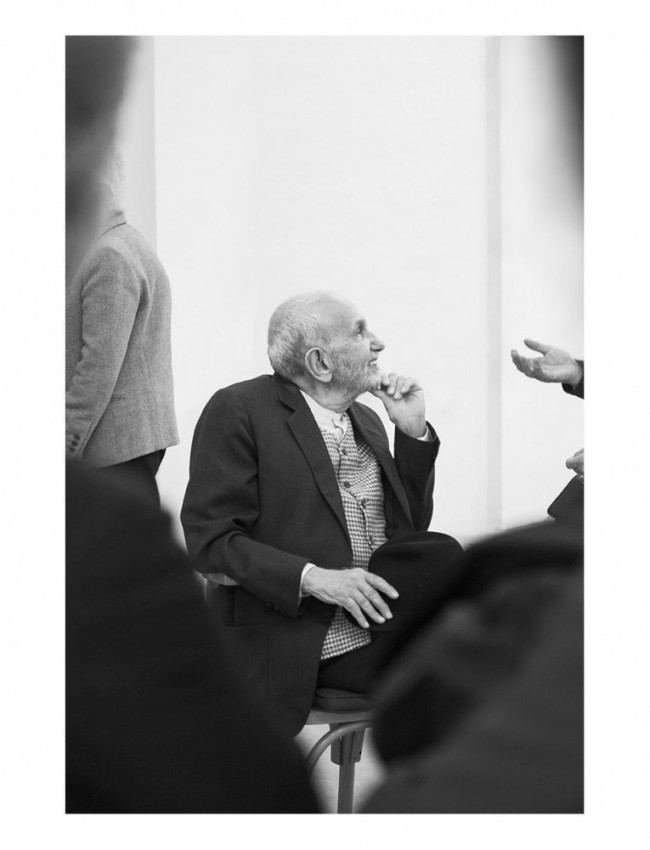

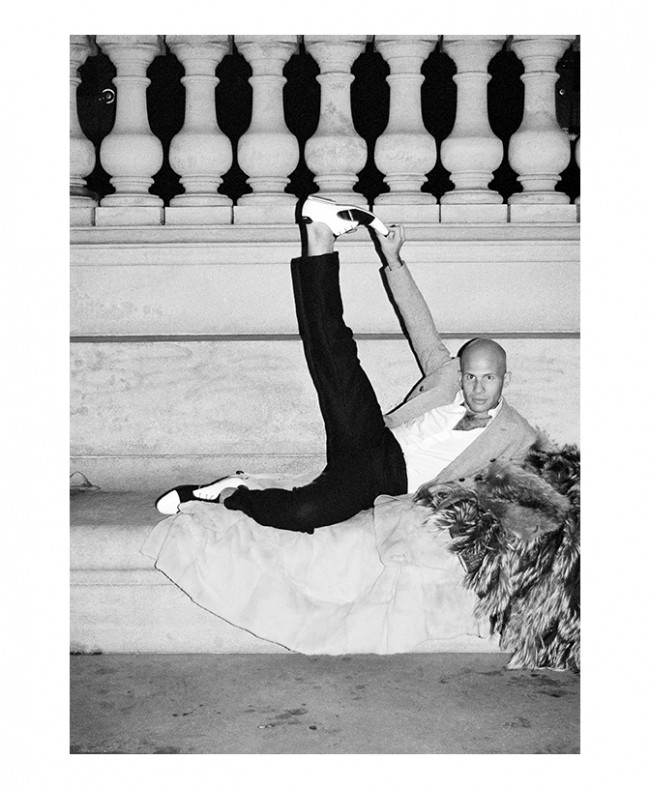

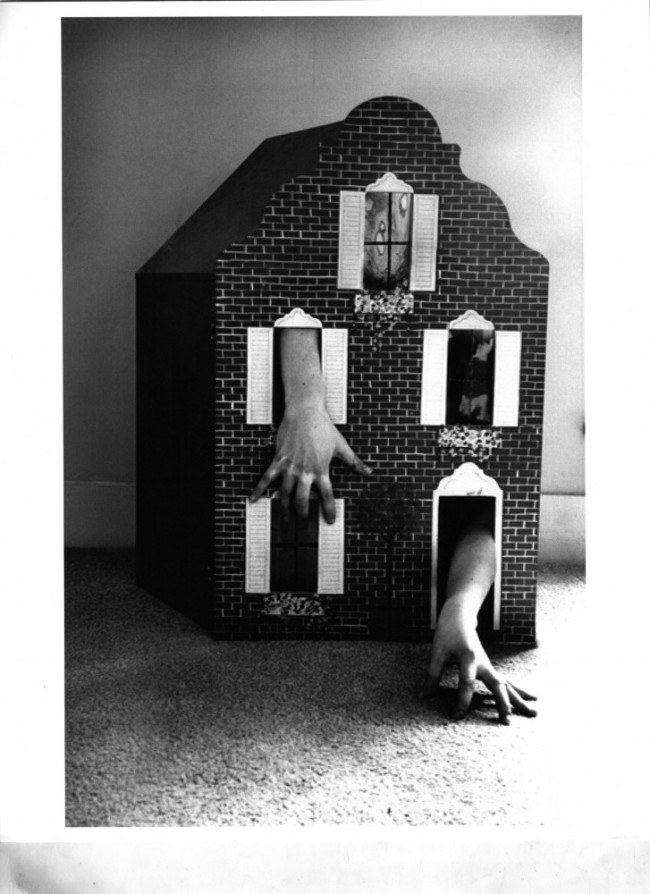

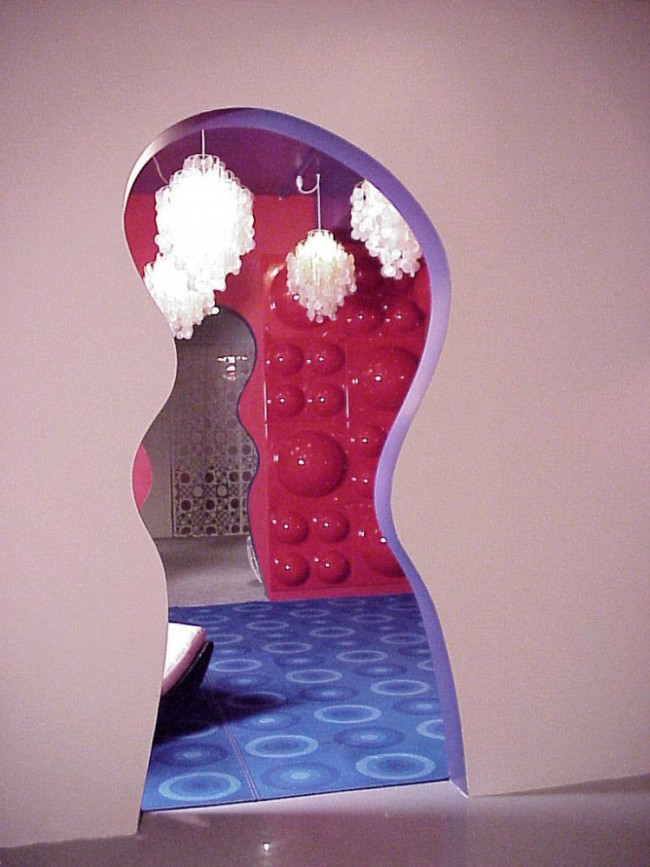

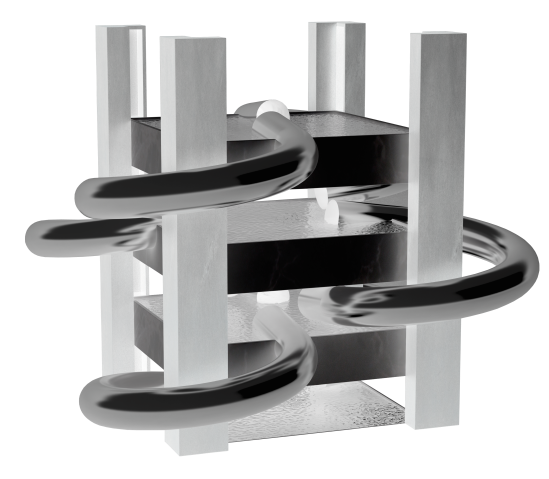

View of Blow Up exhibition. Photography by Timothy Doyon. Courtesy of Friedman Benda.

-

View of Blow Up exhibition. Photography by Timothy Doyon. Courtesy of Friedman Benda.

-

View of Blow Up exhibition. Photography by Timothy Doyon. Courtesy of Friedman Benda.

One of my sons hadn’t spoken to me in weeks since reading my email. I had drafted a suicide note on one of my bad days. My 13-year-old read it, having either hacked or guessed my password, which was strange, since I’d changed my password to something no one would ever guess. I’d changed it to ourdeaddog and I didn’t even like our dead dog and even that didn’t fucking work.

Sometimes I whispered to Ian, told him those three words I thought might reassure him, promised I would stay, but all he did was look away. He didn’t seem to believe me anymore. Though sometimes when I said this I was laughing. My youngest, Dennis, was six. It was like he was on drugs without being on drugs. He didn’t know about pain or grief or suffering yet. I admired that about him. The next day, when I was not on drugs, I felt like I was sinking into the floor. I couldn’t get up. I felt a little dramatic, like I was on fire. Thought a demon had invaded my body, filled it with gasoline, and lit a match. That was what depression was like for me, a kind of burning that wouldn’t end.

When I was high, everything was better. Cleaning, laundry, making the beds, pouring coffee, fucking my husband, whatever. I floated from room to room on drugs, and I could perform myself as a true masterpiece of a woman. As sweet, subservient, and smiling. My family was happy for me.

One day, I doubled the dose and took five drops. For some reason I thought that would be good. When I opened my eyes, my sons were sitting on the couch. The Christmas tree shimmered with a glow far brighter than any light I’d ever seen. It was amazing. I felt like I was part of it and everything in the room. The silk curtains, wool rug, stone fireplace. I was the smudge on the gold-plated coffee table, which I now realized didn’t go with the baby blue on the walls. I stared at our cat who was me. Then at my sons, who really were me, with their skin like mine, brown hair, a faint gray in their eyes. I was that disdain in Ian’s voice when he said, What do you want? That was me. Had Mary ever wanted kids? I thought about her now, giving birth to a boy who would later be crucified. One day, her son would rise from the grave and men would surround him, stick their fingers in him to prove he was real. I saw it in a painting once by Caravaggio. Jesus takes a man’s hand and guides it deep into his wound. See? He seemed to say, I’m dead but alive.

-

View of Blow Up exhibition. Photography by Timothy Doyon. Courtesy of Friedman Benda.

-

View of Blow Up exhibition. Photography by Timothy Doyon. Courtesy of Friedman Benda.

-

View of Blow Up exhibition. Photography by Timothy Doyon. Courtesy of Friedman Benda.

For the first time I wanted to cry because I felt fine. Not scared. No pain. No worries. Yeah, we were all gonna die. But the body was a body and it went. I needed music. I turned the TV off and someone said, Hey! And I think they turned it back on, but I didn’t care, I was listening to the universe. Suddenly the cat jumped weird. That was funny, I thought, and started laughing hysterically like a crazy person, like the stereotype of the high person that I was.

By now, Dennis was giggling, and I took the opportunity to lift him into my arms and we danced from room to room. We weren’t even listening to anything. Just going. Everything was really good. It was a great day. Didn’t feel like dying at all. Somewhere a door shut. I guessed Ian had gone to his room. But Dennis stayed. Good, sweet, Dennis, with so much love to give. He really was beautiful. Someday he’d be someone else’s to hold, but right now he was mine and it hadn’t happened yet, that bad day. The day when he’s 16, staring at the fire I started that has gotten out of control, not knowing why or when it’ll happen again. There are things he’ll say, but hasn’t yet, like, You crazy bitch. You crazy fucking bitch.

Text by Micaela Durand.

Blow Up is on view at Friedman Benda gallery, New York until February 16, 2019.