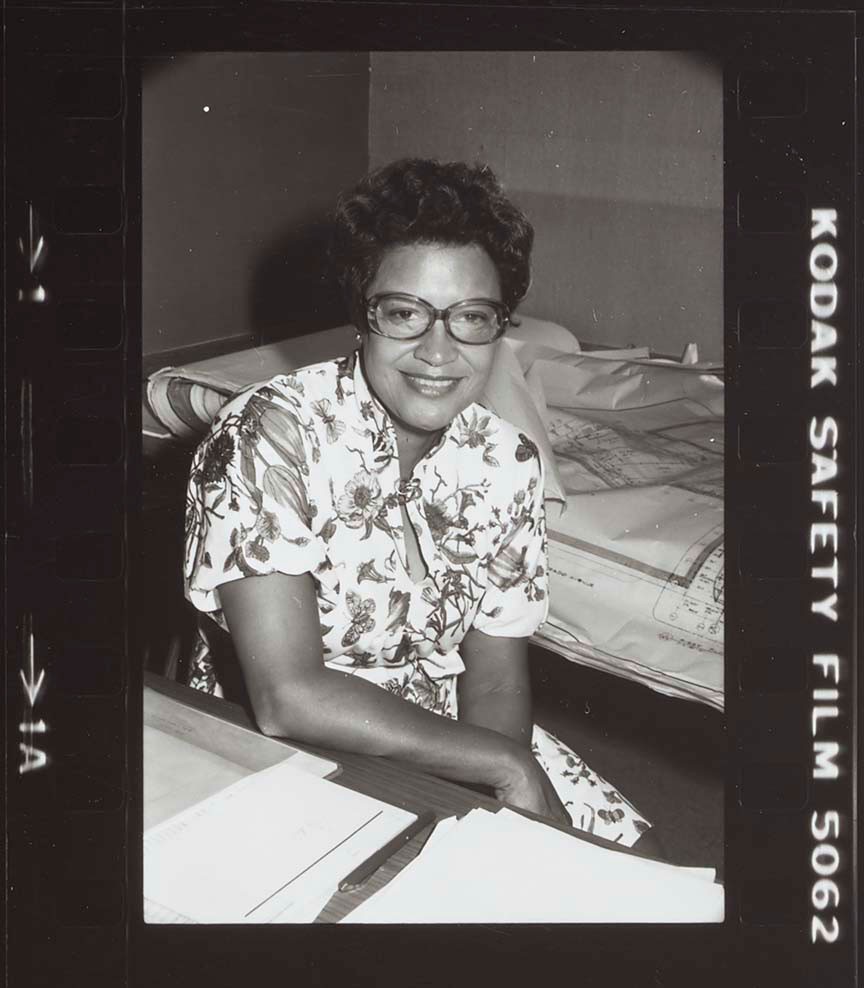

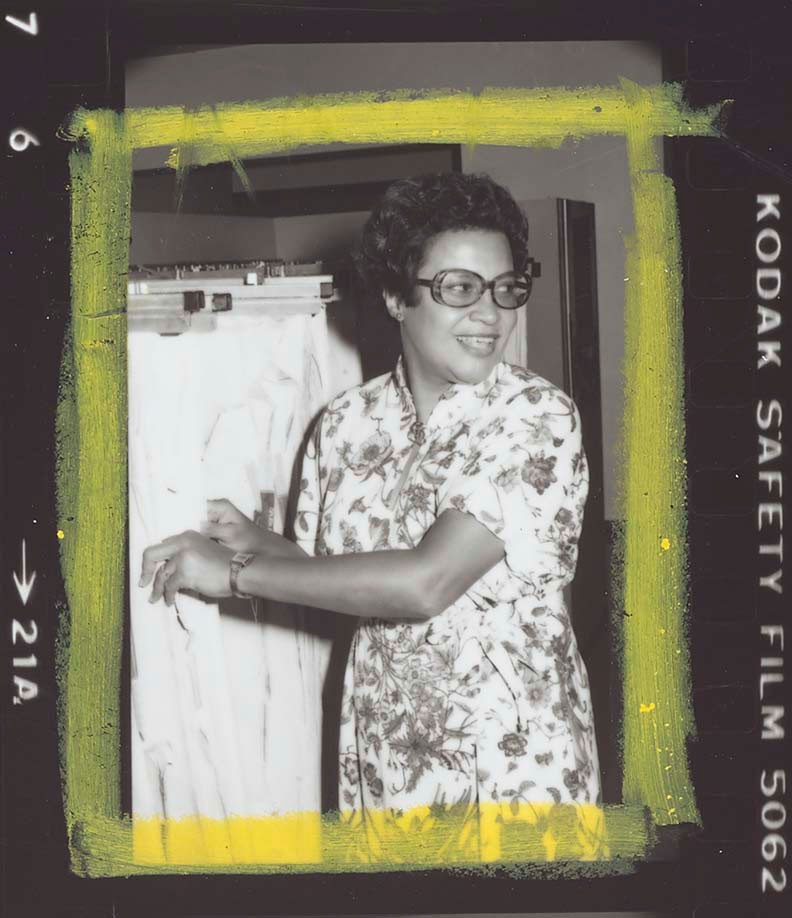

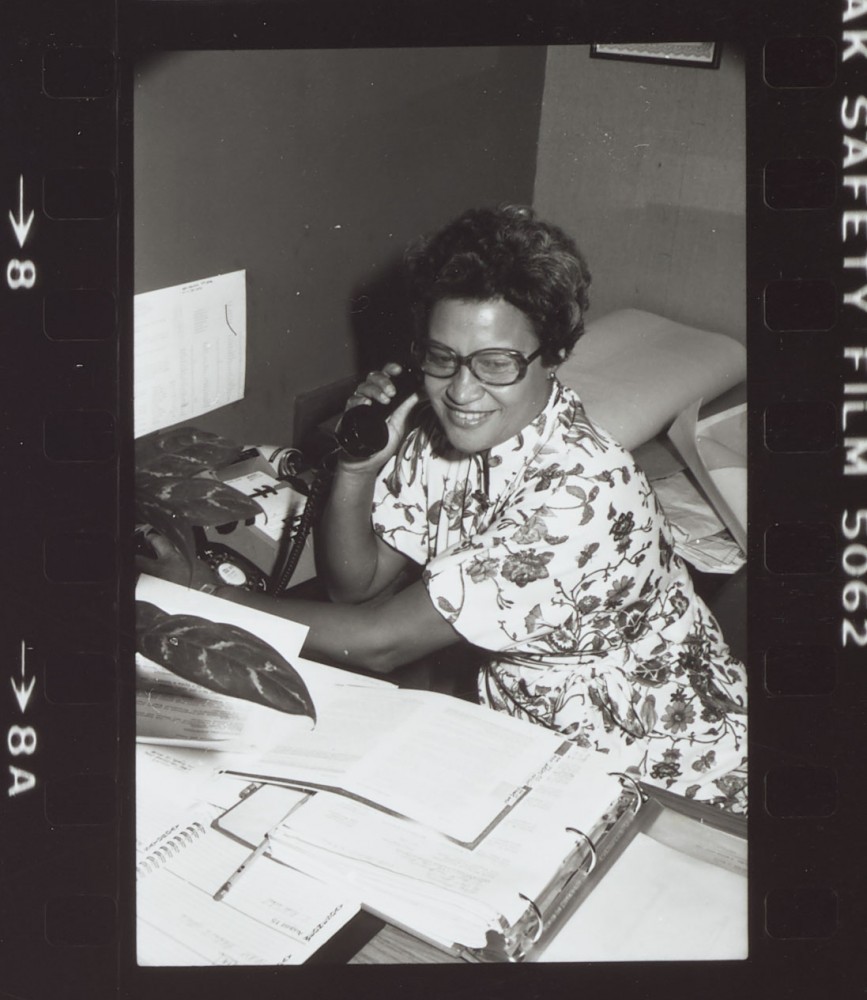

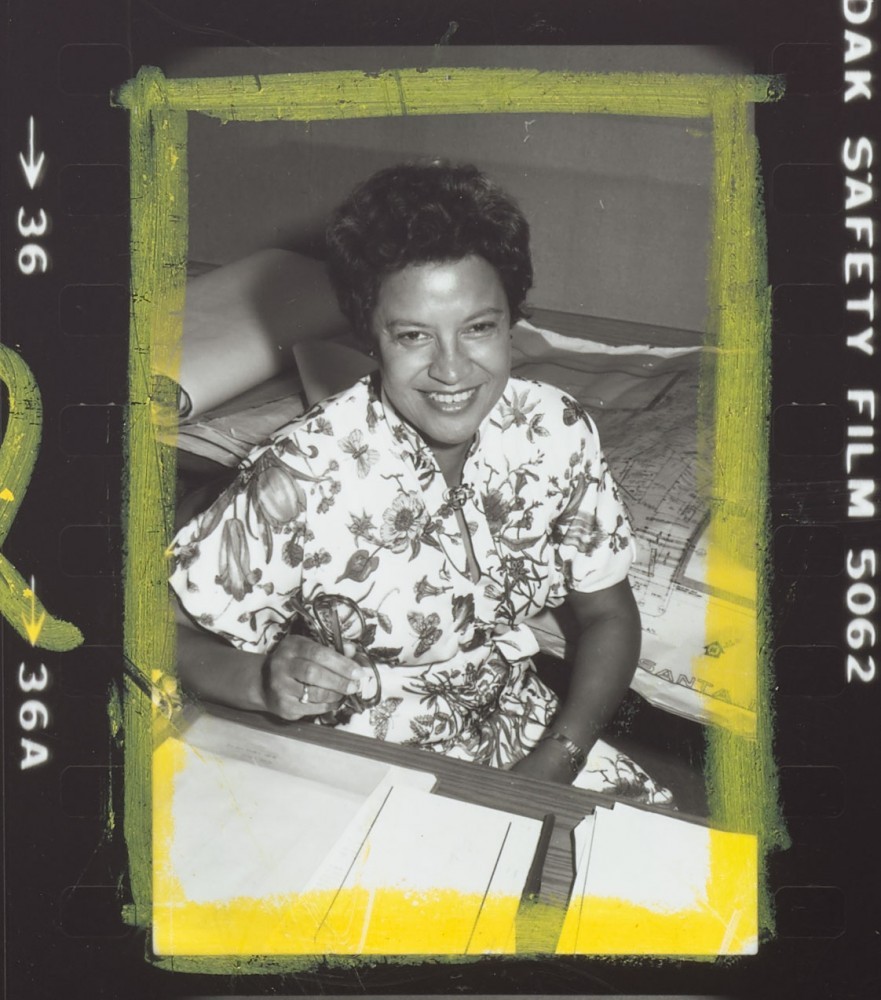

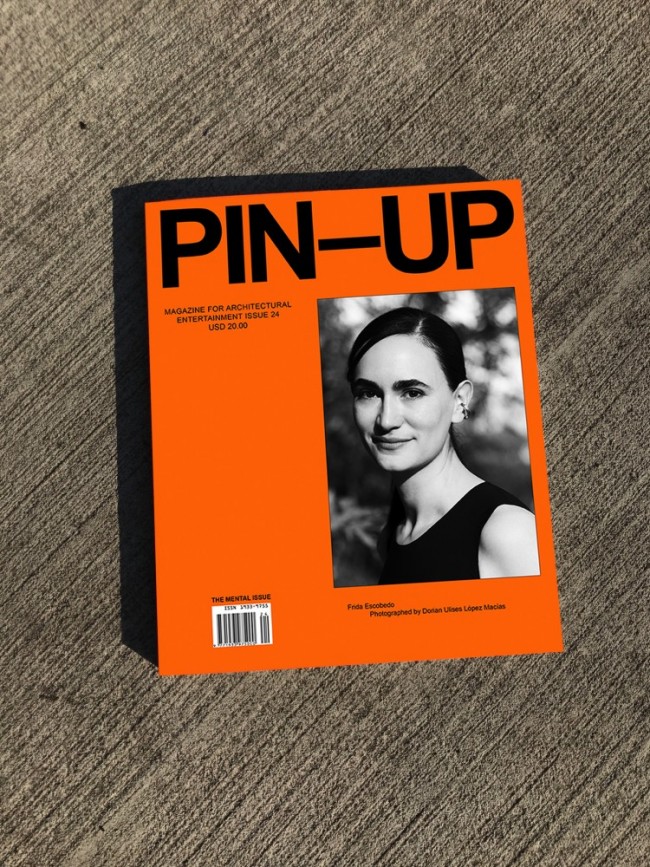

Remembering Norma Merrick Sklarek, an Architect of Many Firsts

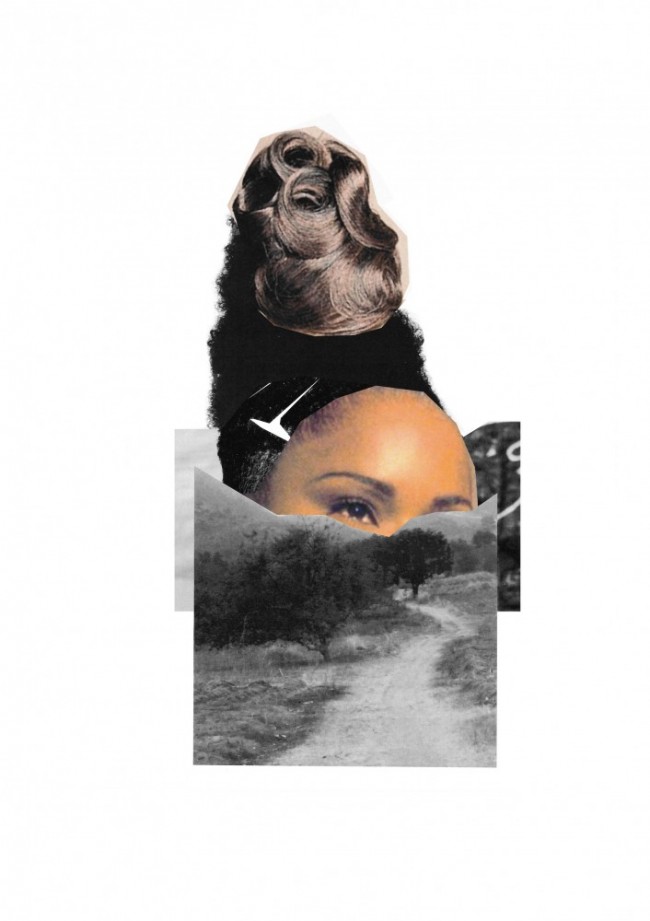

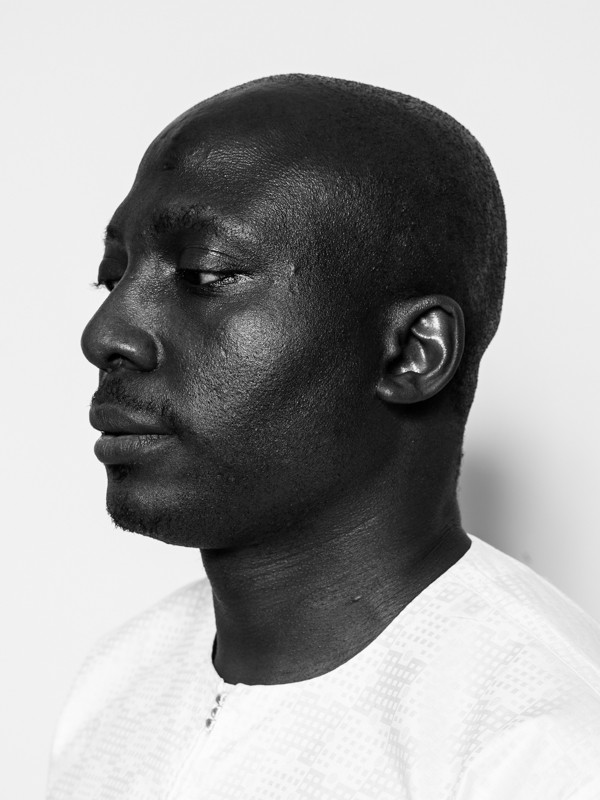

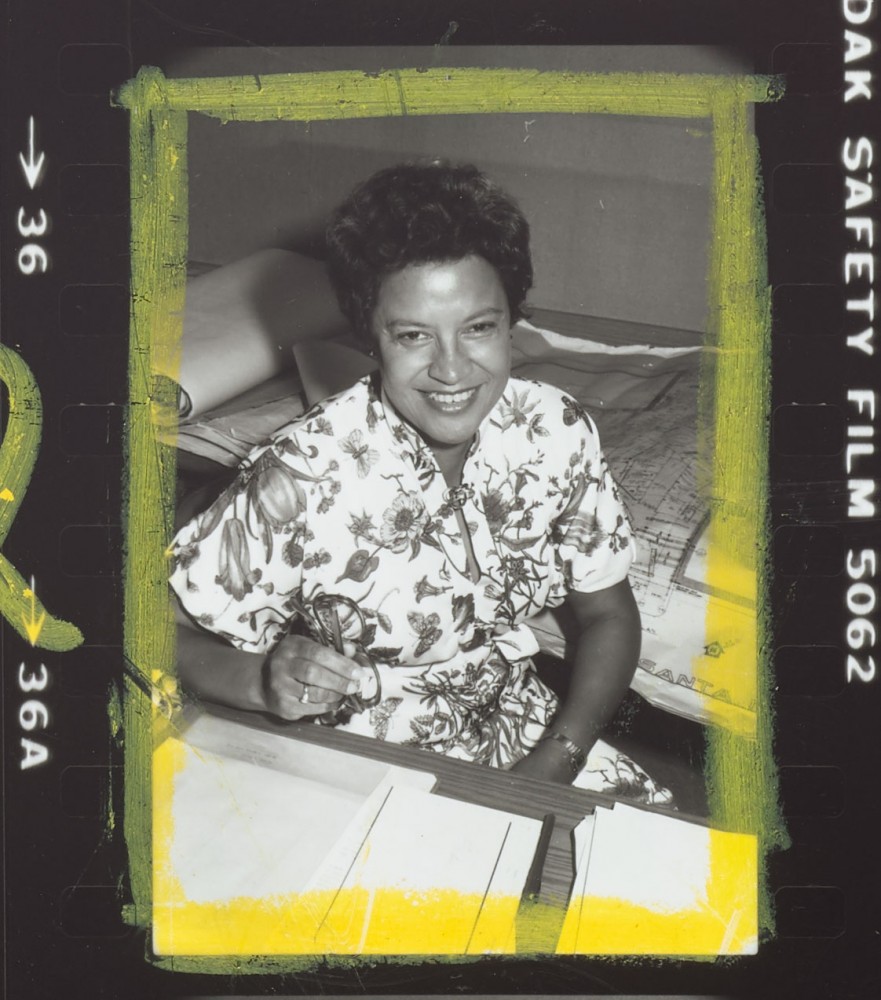

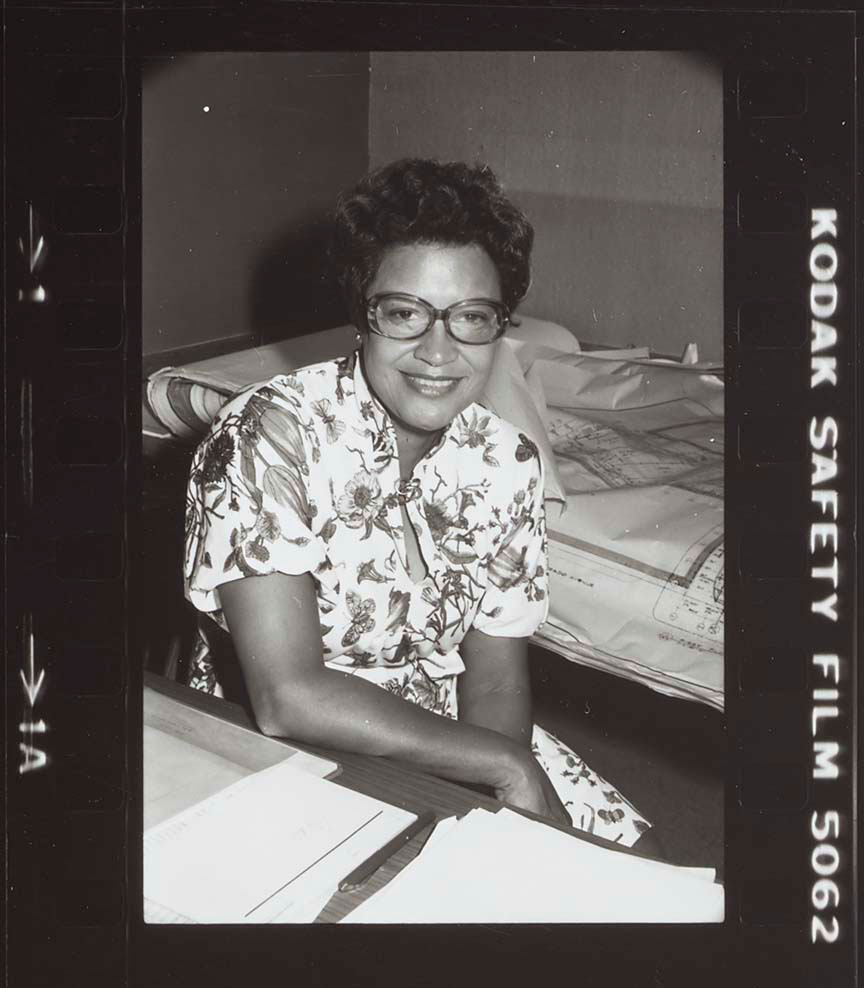

Unknown photographer, Contact sheet of Norma Merrick Sklarek (mid-late 20th century); Silver and photographic gelatin on photographic paper. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of David Merrick Fairweather and Yvonne Goff. Image courtesy Smithsonian.

In 1975, New York-born architect Norma Merrick Sklarek (1926–2012) wrote in a letter to the vice chancellor at UCLA, where she was an architecture faculty member: “As far as I know, I am the first and only Black woman architect licensed in California. I am not proud to be a unique statistic, but embarrassed by our system which has caused my dubious distinction.”* By that time, Sklarek’s recognition as a woman of firsts had only started to make some noise. She was the first Black woman to graduate from Columbia University School of Architecture in 1950, the first to become a licensed architect in the state of New York in 1954, then in California in 1962, and the first Black woman member of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) in 1959 (and later named a Fellow in 1980).

Throughout her career, Sklarek used her professional and academic position to teach and mentor other minorities in the architecture field. Her 1975 letter to the vice chancellor continued: “I have made a standing invitation to the students who need or desire instruction in drafting and presentation techniques to visit my office (to show) them examples of high quality work which hopefully will inspire them.” The offer was made to all pupils, however, “a much larger percentage of the female students than the male, and all of the Black students have taken advantage.”

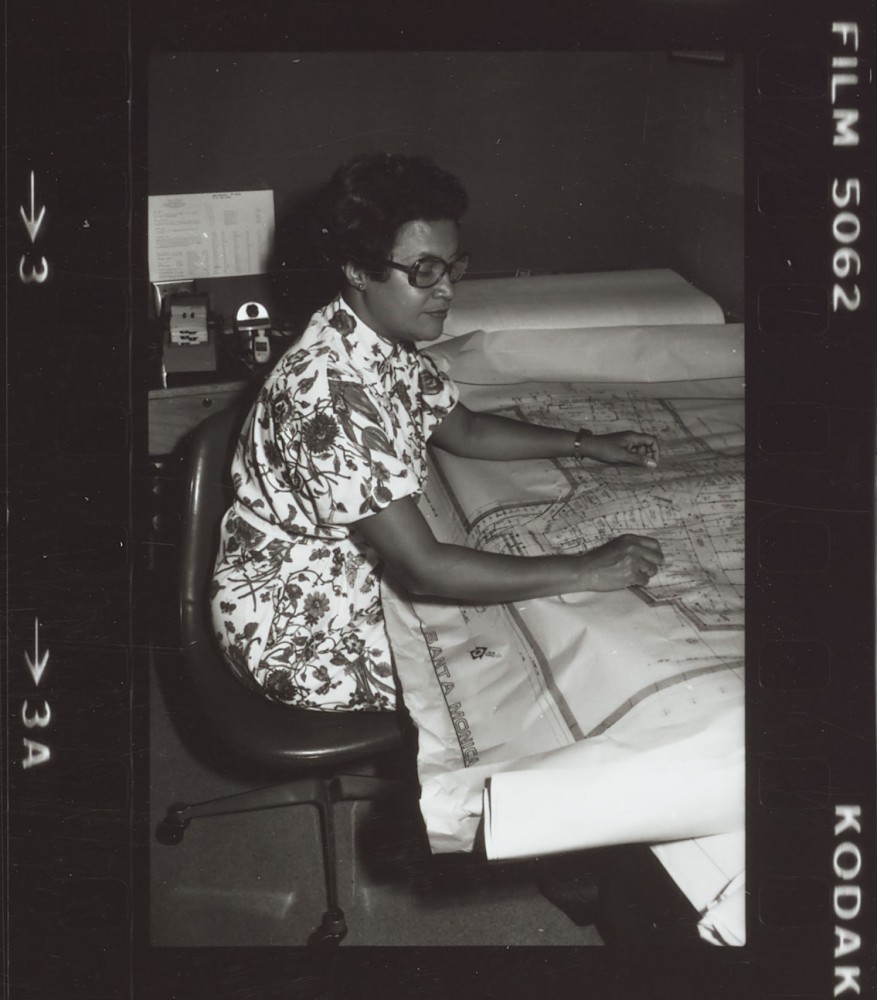

Norma Merrick Sklarek in the meeting room at Gruen Associates (ca.1960). Image courtesy Gruen Associates.

Sklarek wanted to be an example for others, to be the role model that she never had. There were two Black women who had come before Sklarek, but she was unaware of their existence. Beverly Loraine Greene was the first Black woman to become a licensed architect in the United States in 1942 and Louise Harris Brown the second in 1944. The lack of collective memory that resulted in Sklarek’s not knowing these two women speaks to the importance of telling Sklarek’s story, in part so she can function as a motivating exemplary for generations after.

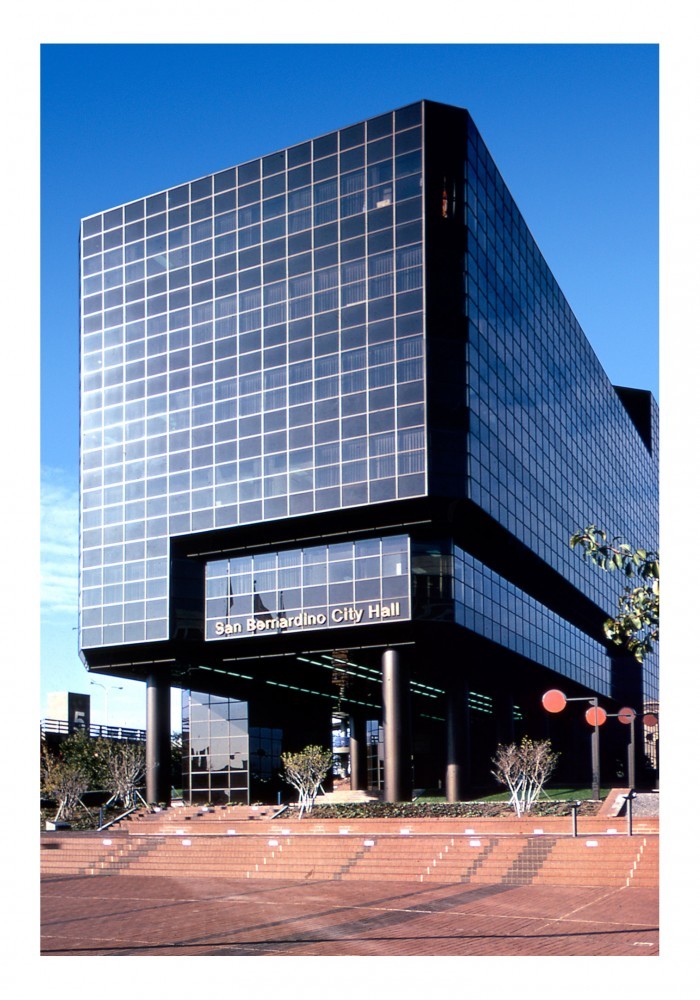

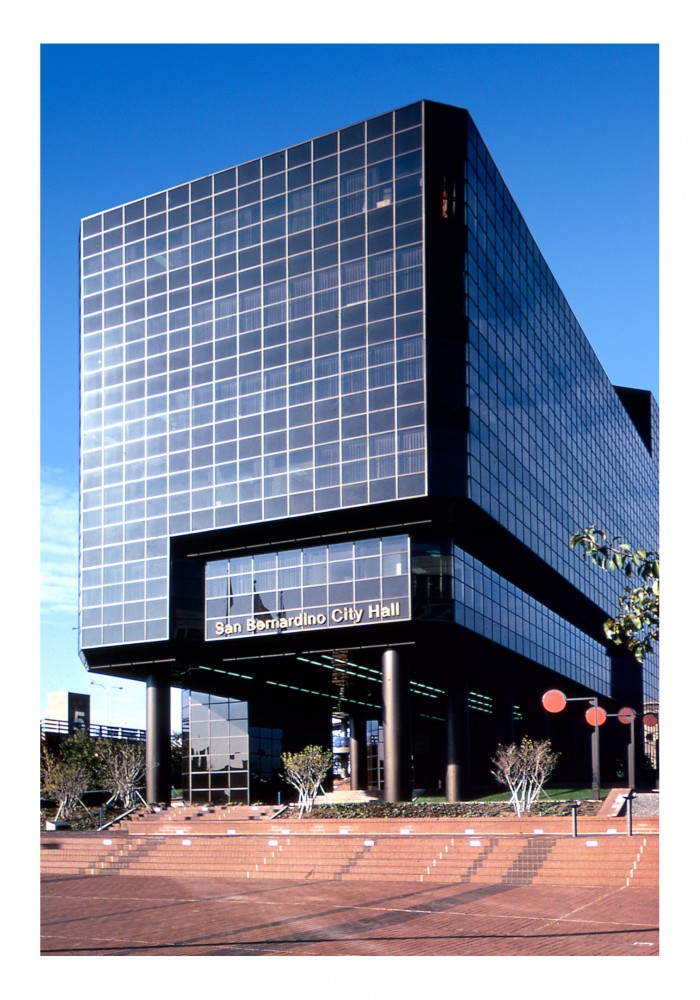

Prior to Sklarek’s licensure, it was only after being rejected from 19 architecture firms that Sklarek was finally hired as a junior draftsperson in the Department of Public Works in New York in 1950 (the same year the Supreme Court banned school segregation). She then worked for Skidmore, Owings and Merrill in 1955, and later joined Gruen Associates in 1959, where she managed large-scale projects including the California Mart (1963), the Pacific Design Center (1978), San Bernardino City Hall (1973), and the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo with Cesar Pelli (1976).

-

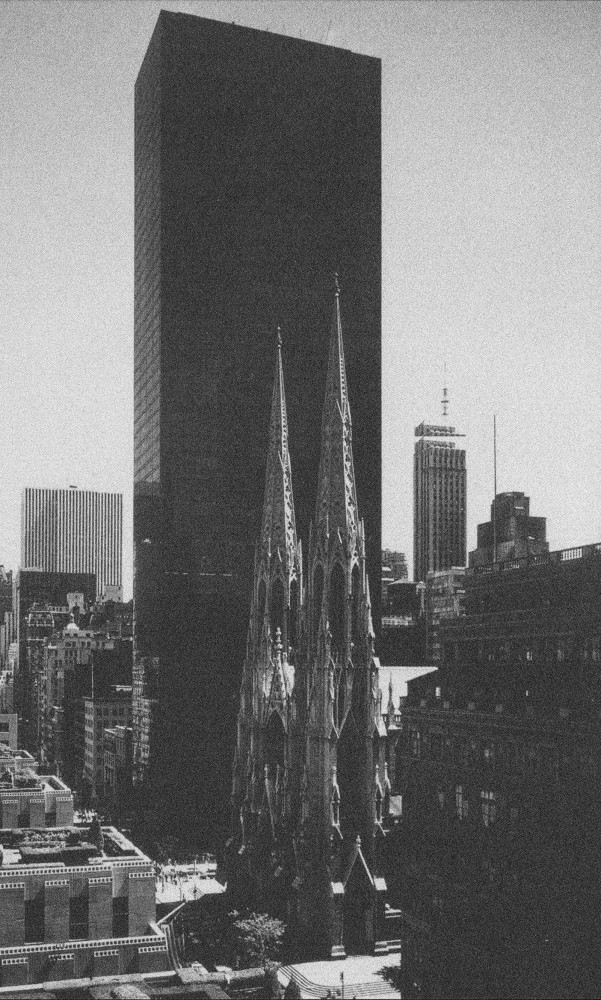

San Bernadino City Hall (1973). Image courtesy Gruen Associates

-

United States Embassy in Tokyo (1976). Image courtesy Gruen Associates

Nevertheless, there have been few inclusions of Sklarek’s career in anthologies and academic discussions. In a recent panel discussion “Redefining Public” at the annual Women in Design and Architecture conference organized by the Princeton University School of Architecture, keynote speaker Michelle Joan Wilkinson — curator of architecture and design at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture – illustrated the few examples that have recognized Sklarek’s exceptional life and work including I Dream a World (Brian Lanker, 1989), illustrating the lives of 75 boundary-breaking Black women; Women Design (Libby Sellers, 2018), focused on pioneering women in architecture and design; and of course, “Redefining Public.”

In addition to Wilkinson, “Redefining Public” brought together a remarkable group of women to discuss Sklarek’s legacy, including former colleague Kate Diamond, together they founded Siegel-Sklarek-Diamond, as well as other practicing architects, scholars, and curators such as Allison Grace Williams, Carolyn Armenta Davis, Sharon Sutton, and Gabrielle Bullock. Moderators V. Mitch McEwen and Jennifer Newsom navigated the conversation to touch upon the struggle for recognition and authorship under the framework of white supremacy, the outdated institutional Beaux-Arts atelier pedagogy model, as well as building community and mentorship in spite of hostile circumstances.

-

Unknown photographer, Contact sheet of Norma Merrick Sklarek (mid-late 20th century); Silver and photographic gelatin on photographic paper. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of David Merrick Fairweather and Yvonne Goff. Image courtesy Smithsonian.

-

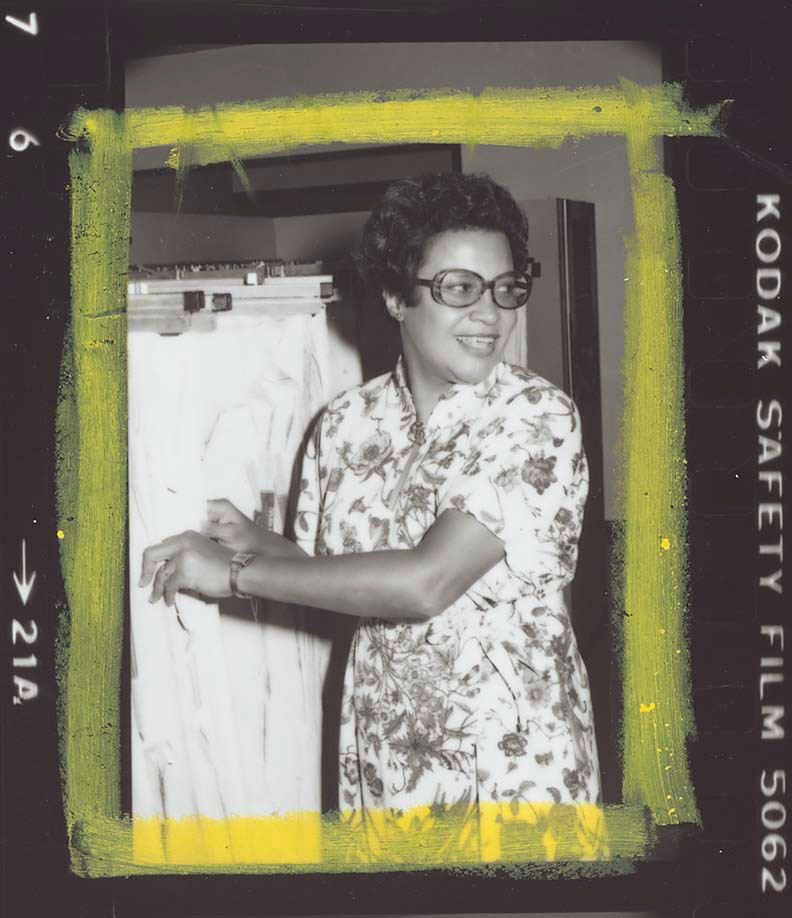

Unknown photographer, Contact sheet of Norma Merrick Sklarek (mid-late 20th century); Silver and photographic gelatin on photographic paper. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of David Merrick Fairweather and Yvonne Goff. Image courtesy Smithsonian.

Wilkinson also spoke of the critical need for dissemination of the work of minority women in architecture and design. In 2016, she began arguably the most important archive of the work of Black architects and designers — Sklarek among them. “As a curator and the first user of Norma (Sklarek)'s archive,” Wilkinson said during her presentation, “I find much value in how Norma managed to play her role and model a life that included five marriages, two children, an active gardening practice, designing and making many of her own clothes and those of her children, regular committee work for her local AIA chapters, teaching, and (many) hobbies.”

While testimonies like Wilkinson’s spoke to how impressive Sklarek’s story is — she not only built big but was committed to an educational vision and achieved excellence on a holistic level — there was a notable lack of attendance by many of the School of Architecture’s student body suggesting a continued disinterest in unfamiliar (or rather, invisible) voices in architecture history.

-

Unknown photographer, Contact sheet of Norma Merrick Sklarek (mid-late 20th century); Silver and photographic gelatin on photographic paper. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of David Merrick Fairweather and Yvonne Goff. Image courtesy Smithsonian.

-

Unknown photographer, Contact sheet of Norma Merrick Sklarek (mid-late 20th century); Silver and photographic gelatin on photographic paper. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of David Merrick Fairweather and Yvonne Goff. Image courtesy Smithsonian.

The work being made to preserve Sklarek’s legacy, however, means that she may not be an unfamiliar name for much longer. Carla Jackson Bell (Tuskegee University) and Kathryn Anthony (the Illinois School of Architecture) are currently working on a documentary, funded in part by the Graham Foundation, focused on issues of race and gender in architecture. The film, which they started shooting in 2005, includes an interview with Sklarek then in her 80s. It’s heartening there’s momentum behind telling Sklarek’s story in a way that engages with the larger systemic and social inequities that contribute to the lack of cultural diversity in the field of architecture. But after absorbing the discussion “Redefining Public” and all the brilliant contributions that were made, one lingering feeling remains: the work here isn’t done.

*The letter from which this quote was taken is part of the Norma Merrick Sklarek Archive at the National Museum of African American History and Culture. It is an unpublished document that is not yet available for viewing nor accessible to the public at this time. It was presented publicly for the first time by Dr. Michelle Joan Wilkinson, curator of architecture and design at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, during her keynote address for “Norma Merrick Sklarek: Redefining Public,” a conference that was part of the annual Women in Design and Architecture series organized by the Princeton University School of Architecture on March 28, 2019.

Text by Natalia Torija Nieto.