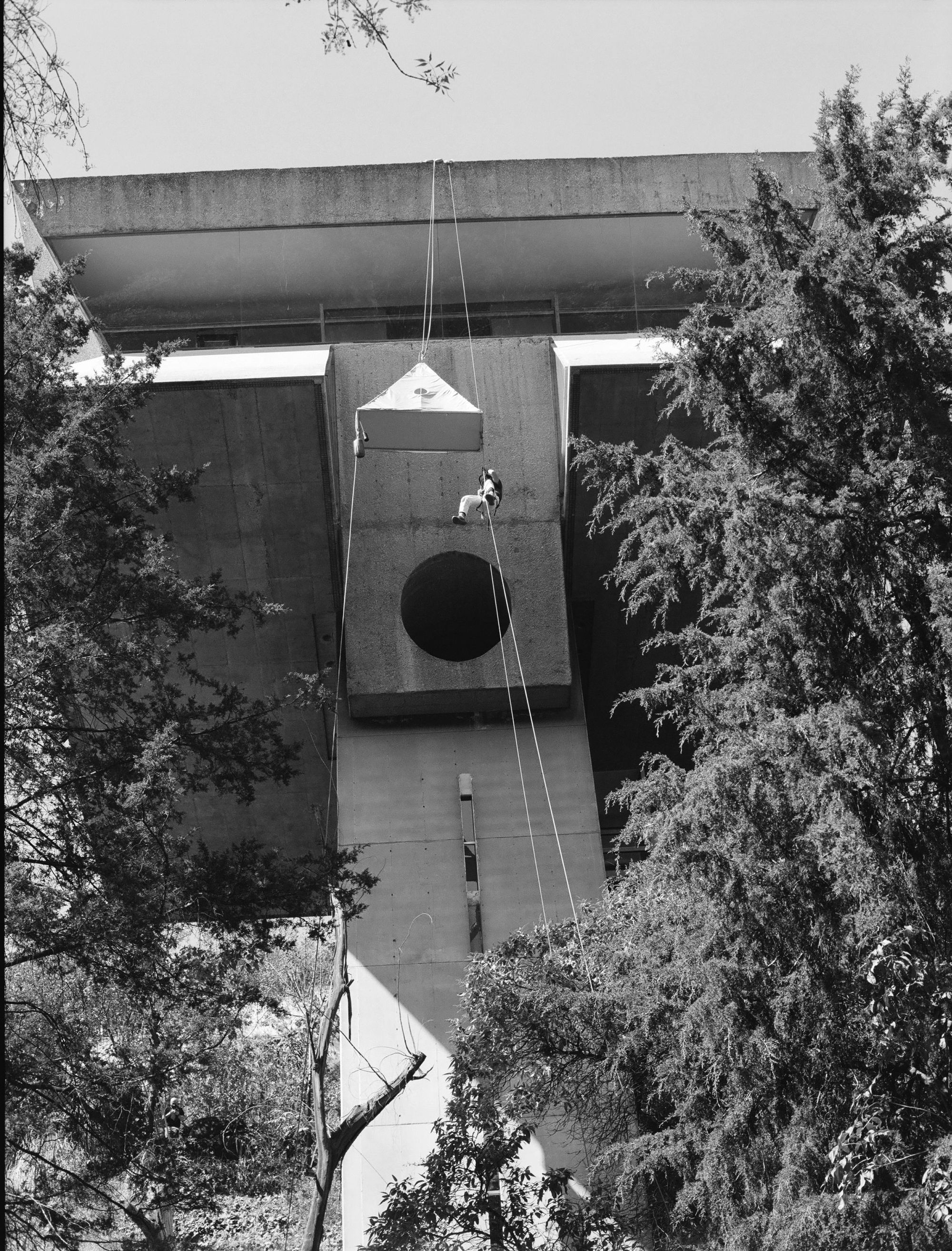

Lucas Cantú’s Espacio y pensamiento: Nuevas Perspectivas sobre la casa del árbol, 2022. Photo by Paul Maffi, courtesy of PEANA.

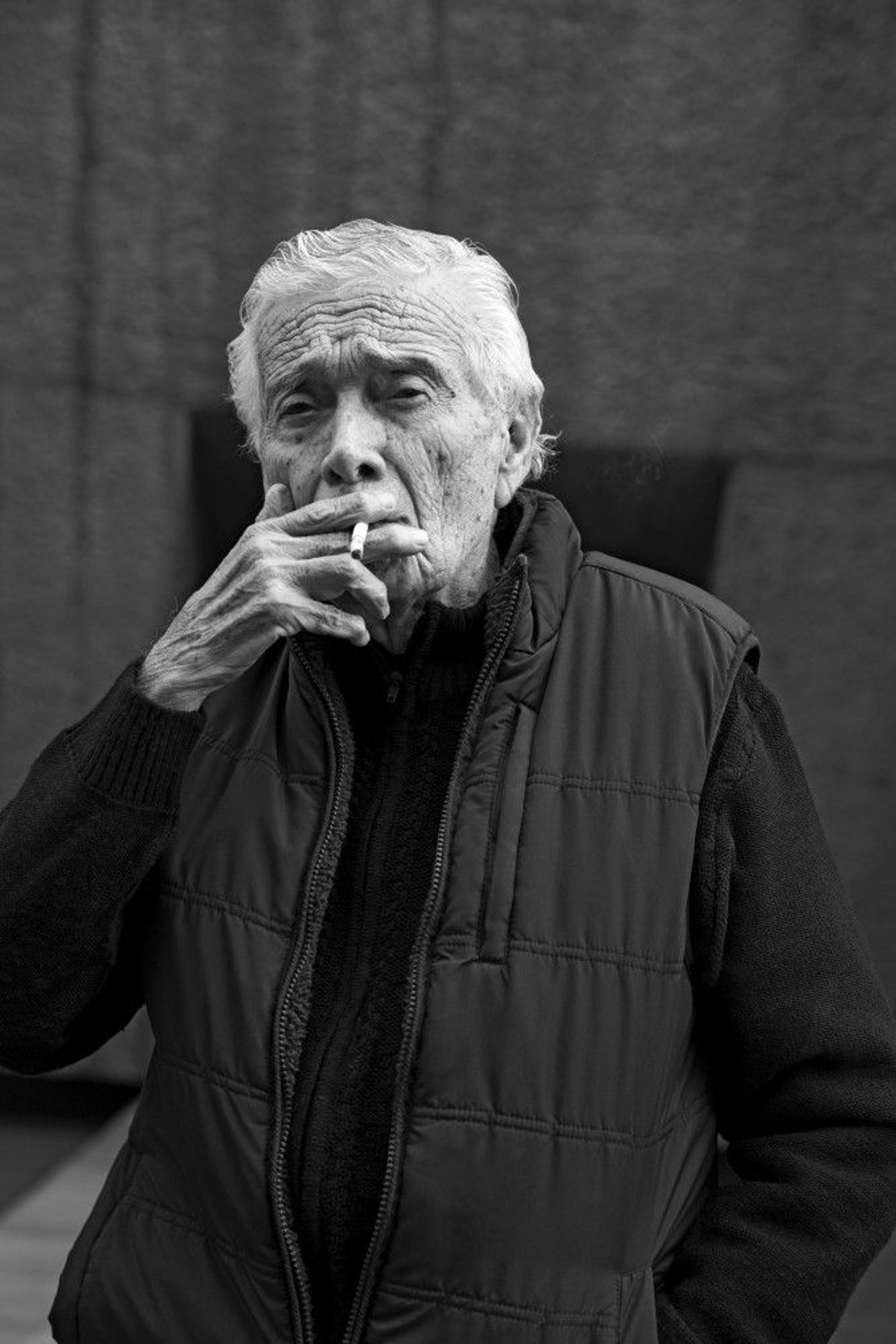

Agustín Hernández photographed by Dorian Ulises López Macías for PIN–UP 29, Fall Winter 2020/21.

On a recent evening Agustín Hernández, the nonagenarian maestro known for injecting Mesoamerican semantics into the brute vocabulary of modernism, could be found mingling with a young fashionable set at the concrete tree-house he built almost a half-century ago. Hernández built PRAXIS, Taller de Arquitectura in 1975 as his office and play-pad. The 97-year-old came sharply dressed, interacting with guests in between signing autographs, sipping cuba libres (rum and cokes), and chewing on candy gummies. He wondered where the ashtrays had gone — he still smokes a pack a day, and the cigarette marks on the slate gray wall-to-wall carpets prove it.

At one point Hernández walked up the stairs to his bedroom and saw a new bronze cast of a sculpture he originally made in 2005, his version of the pre-Columbian reclining statues known as Chac Mool. He paused and caressed the smooth black figure while remarking its beauty, then sat down on the platform bed across from the sculpture and began to recite a poem he once wrote about it. As all this went on, a peculiar yellow tent hung, precarious and serene, from the iconic structure, visible through its expansive slanted windows. It was like a meeting of alien forms — two giant interlocking stone pyramids, and a smaller prism in canary nylon — suspended in time and space.

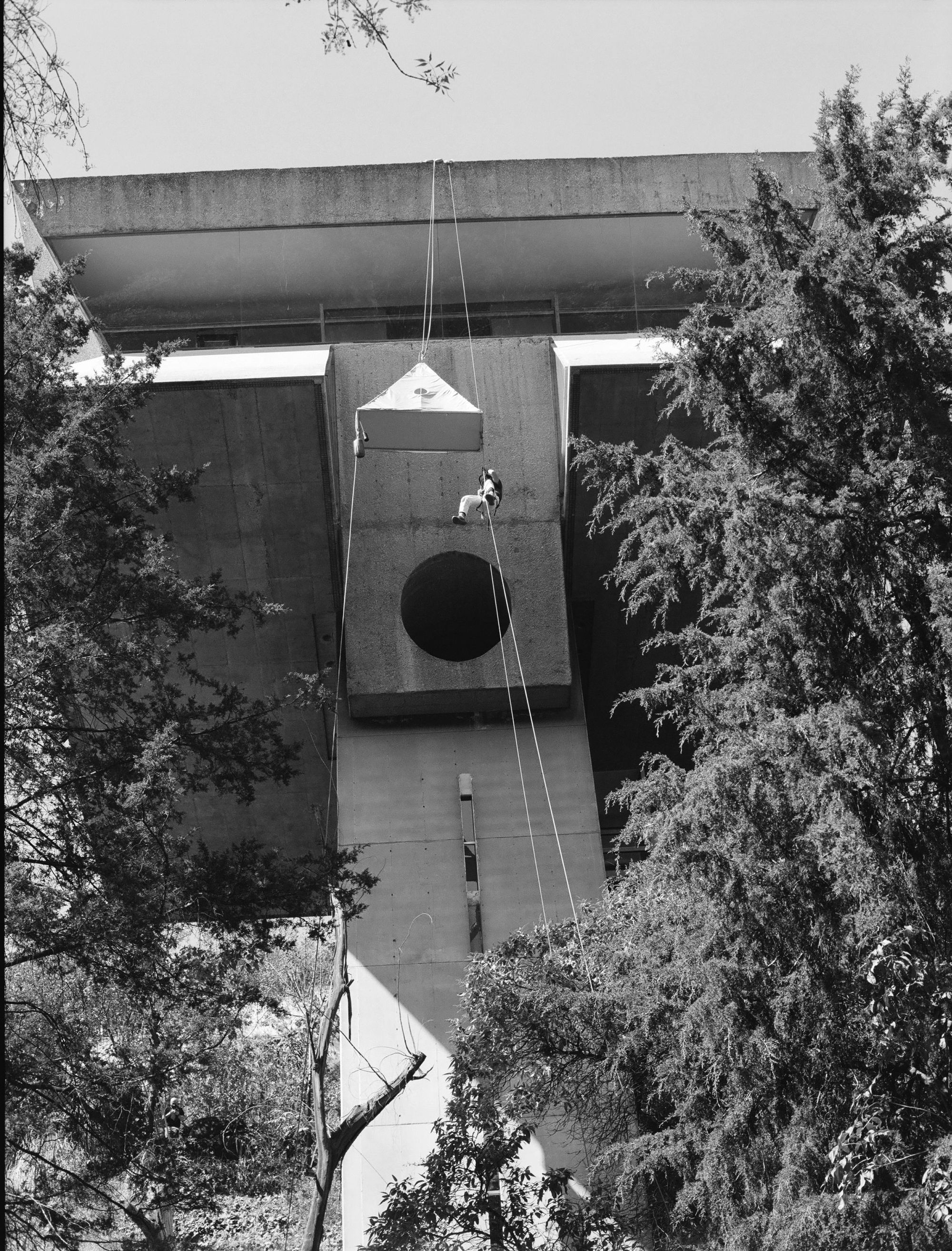

Lucas Cantú’s Espacio y pensamiento: Nuevas Perspectivas sobre la casa del árbol, 2022. Photo by Paul Maffi, courtesy of PEANA.

Agustín Hernández’s Taller de Arquitectura. Photo by Paco Alvares, courtesy of PEANA.

This year’s Mexico City art week included no shortage of dinners, performances and events, often in strange or striking spaces. But judging by Instagram, the most popular location was a rarity with architectural pedigree —Hernández’s bastion of late modernism. PRAXIS had reopened for a limited time for an exhibit of works by 15 practicing artists relating (some more than others) to Hernández’s remarkable legacy. The debonair architect’s presence on opening day was an added bonus.

The credit for unbeatable-venue of the week goes to PEANA, a Monterrey-based art gallery founded and run by Ana Pérez Escoto. Through off-site shows like the one at PRAXIS, Pérez Escoto stages carefully planned revisions of architecturally notable buildings and the figures that created and inhabited them, filling them with works by artists who negotiate materiality and space. In late 2020, the gallery approached Hernández’s family about hosting an exhibition exploring the architect’s oeuvre while placing it in conversation with contemporary works of art at his famous tree-like Taller.

Agustín Hernández reading his poem. Photo by Lucas Cantu, courtesy of PEANA.

Agustín Hernández’s Chac Mool (2005-2022). Patinated bronze. Photo by Caylon Hackwith, courtesy of PEANA.

Hernández, who had closed his studio for good at the beginning of the pandemic, agreed, allowing for the exceptional structure to be temporarily open to the public before it returns to an uncertain future. Will an Elon Musk, Benedikt Taschen or Ye-type swoop it up as a trophy house or party lair? Will it fall prey to developers or new owners indifferent to its significance? Can it host more art-related initiatives, like PEANA’s, that pay tribute to its history? Will it languish in oblivion, decaying until foliage and pollution swallow its sharp contours? The questions remain, but for now, What Lies Under the Tree, the exhibit co-curated by Pérez Escoto and Carlota Pérez-Jofre, provides one path to keeping the edifice and its creator’s vision alive.

The exhibit also afforded Hernández the disorienting experience to witness his work-and-live space of over four decades as interpreted by others. On the first of three levels, PEANA took the architect’s office as the starting point. Hernández’s desk and other office furniture were concealed with handsome minimalist displays by architecture firm Sala Hars, while maquettes Hernández left behind, including one of his sprawling Colegio Militar, provided a curatorial roadmap. The idea of the architectural model as three-dimensional object informed several works, including a Brancusian wood and gesso sculpture by Carlos H. Matos (one half of Tezontle) and a concrete-and-steel pyramidal ‘house’ by Pedro Reyes. It becomes clear Hernández is a hero to many younger artists whose work references the master’s use of pre-Hispanic volumes to signify a modern Mexican identity.

Front L to R: Pedro Reyes’ Pyramid House, Agustín Hernández’s TAU-IK (1998-2002), Cabeza de Chac Mool (2002-2022), all made from volcanic stone. Photo by Caylon Hackwith, courtesy of PEANA.

Pedro Reyes’ Pyramid House. Photo by Caylon Hackwith, courtesy of PEANA.

But wherever he is present, Hernández tends to steal the show. The most enticing parts of Under the Tree showcase his talent, from photos of his earliest apartment building that point to his inclination towards pure geometries and of models he made out of shoe boxes when he was eight years old to gorgeous conceptual drawings and artifacts documenting planned buildings in Japan and Germany that sadly remained unrealized. Few people know Hernández is also a dedicated sculptor, and the exhibit includes special new editions — in volcanic stone and patinated bronze — of sculptures Hernández has created over the years.

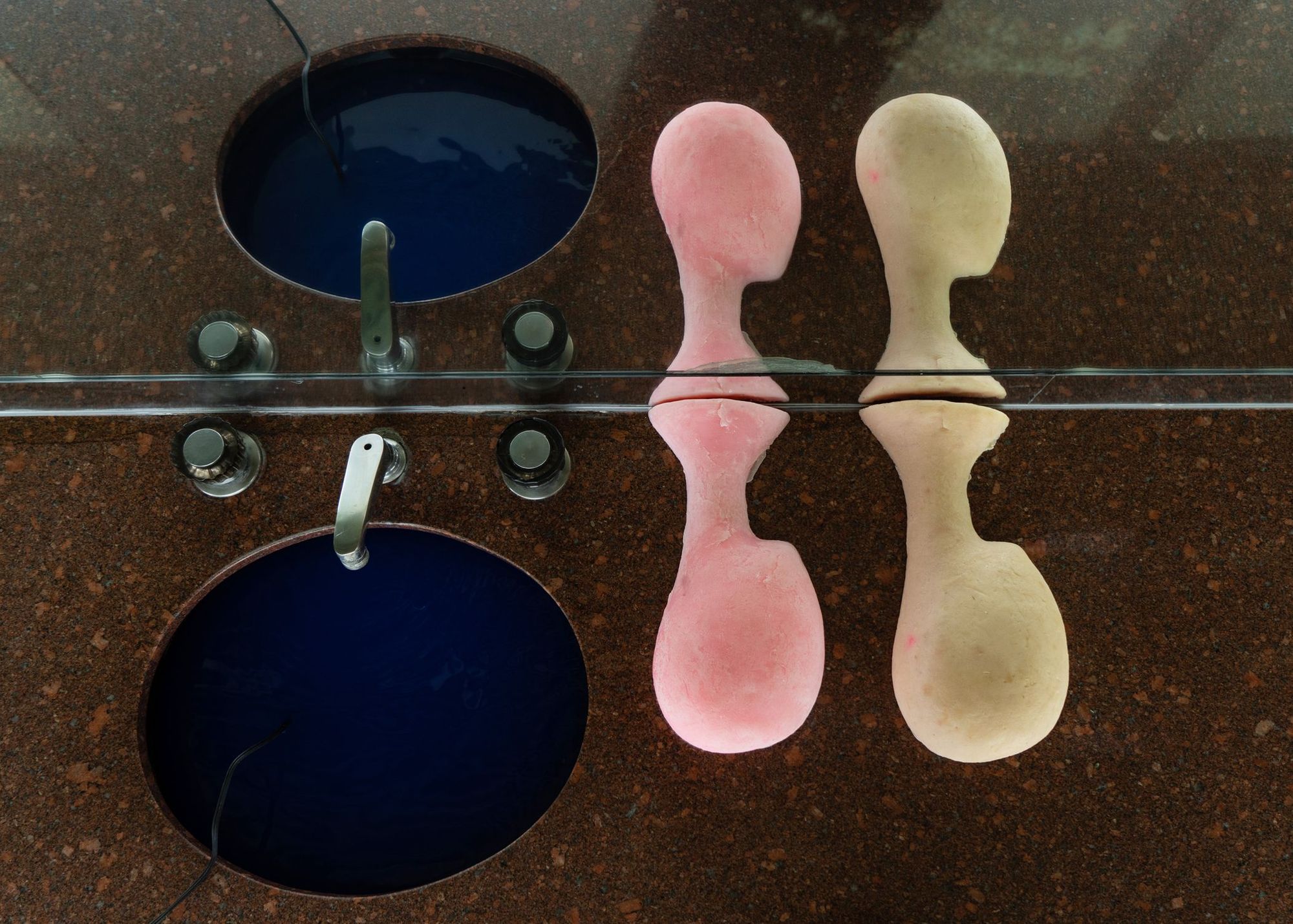

In the sleek apartment Hernández kept above his office and the library at the top of PRAXIS, more artworks are inconspicuously placed on the aforementioned gray carpets, tucked amid rows of books, subtly strewn in hidden corners, and in one particularly effective instance, unsuspectingly woven into the architect’s bathroom. Artist Tania Pérez Córdova worked there with nothing but pigment, glycerin soap, and a water pump. It all feels eerily intimate, as if Agustín or a fantastical creature living in the surrounding trees might appear any moment.

Tania Pérez Córdova’s Scene for a bathroom (2022); glycerin soap, pigment, and water pump. Photo by Caylon Hackwith.

ASMA, Serpiente (2020). Cast in metal alloy. Photo by Diego Berruecos, courtesy of PEANA.

As for the pendant yellow tent outside, it’s a site-specific piece by Lucas Cantú, Tezontle’s other half. Hernández once stated he built PRAXIS as a secluded refuge where he could disconnect from the city, an idea Cantú — an avid camper and proponent of disengaging from technology — responded to with his levitating tent. While the last few weeks have seen hordes of curious admirers alight in posh Lomas de Chapultepec to peek into the improbably skybound studio and gawk at the sexy personal universe of the man who conceived it, Cantú’s work suggests another possible existence for Hernández’s mysterious flying space-ship: as a place of reverie.

Hernández was born on February 29, 1924. Even though 2022 isn’t a leap year, on Tuesday the architect will celebrate his 98th birthday with friends and family at his gravity-defying Taller. ¡Feliz Cumpleaños maestro!

Lucas Cantú’s Espacio y pensamiento: Nuevas Perspectivas sobre la casa del árbol. Photo by Paul Maffi, courtesy of PEANA.