ARCHITECTURE AND SKATING

For Alexis Sablone, Everything Is a Surface

by Jonathan Olivares

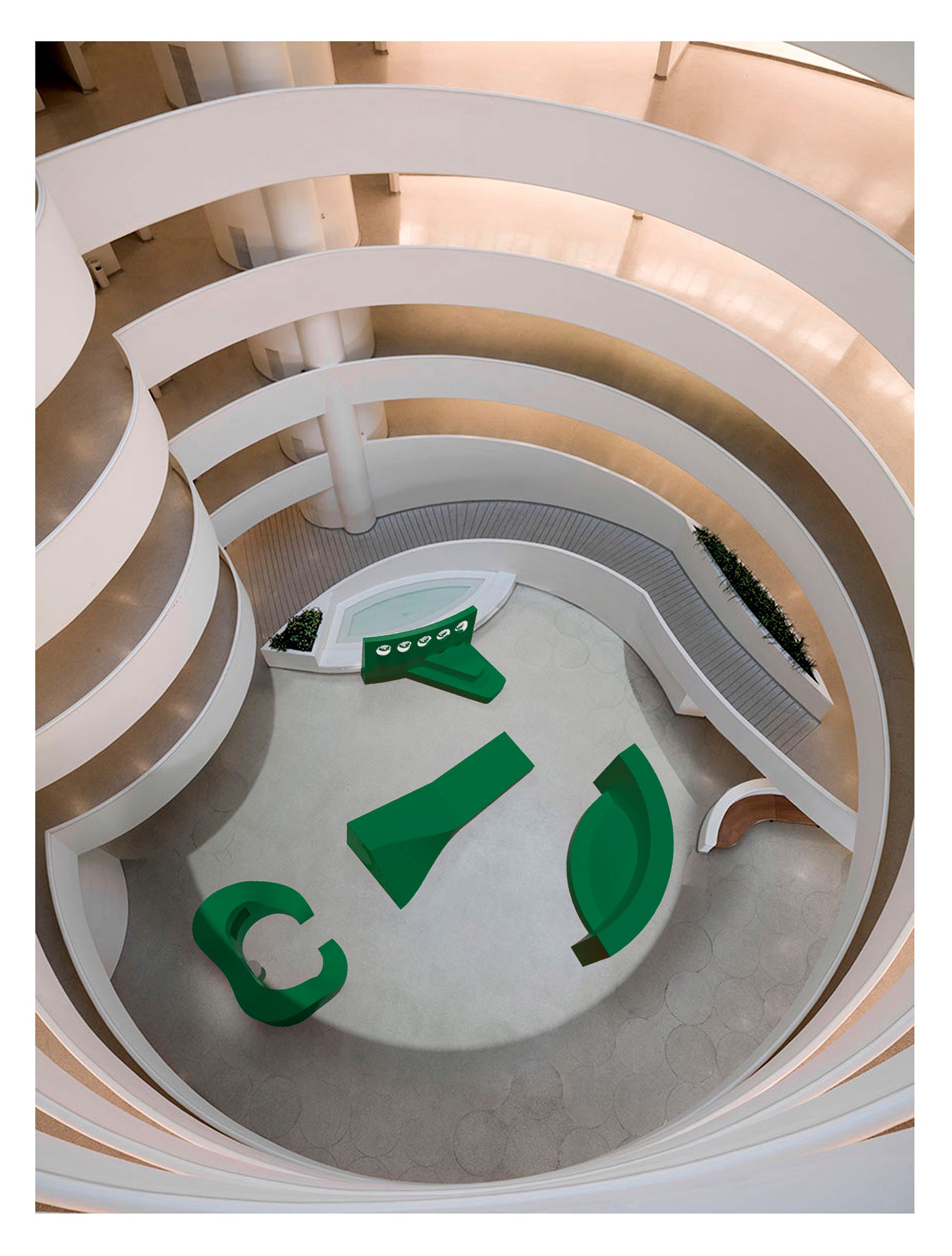

Alexis Sablone skating the iconic Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum spiral as part of the AS-1 event in 2023. Photo by Jonathan Mehring.

At 2024’s the World Around Summit, Alexis Sablone began their talk with a photo of the New York State Supreme Courthouse. An architect, they said, would focus on the Corinthian columns or the sculpted pediment, but a skateboarder would notice one long, sloping surface on the side of the building — the perfect blank slate to grind on or jump from. “As a skateboarder, your familiarity with the site... would be focused on form... and yet, it would have nothing to do with the so-called architectural history of the courthouse.” A competitor in the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, Sablone knows better than anyone the skater’s intimate relationship with the built environment, which results in a more finely-tuned understanding of the small details of certain buildings or streets than even the architects or planners who designed them could claim. Like all skateboarders, Sablone — who once rode the Guggenheim’s iconic spiral, a challenge in itself given the slope and run of the unending ramp — values those smaller, “unassuming blips in the everyday landscape,” like “a street median, a gap in the sidewalk, a fire hydrant on top of a hill.” Skateboarding is just one of their many talents, however. The Connecticut native, who holds a BA from Barnard College and a master’s in architecture from MIT, runs a thriving practice as an architect, designer, and multidisciplinary artist. Armed with the spatial awareness that skaters use on a daily basis, they have created large-scale interactive sculptures and public projects that appeal to skaters and non-skaters alike, blurring the boundary between skatepark, playground, and public garden. With their first big project, Lady in the Square (Malmö, Sweden, 2021), Sablone arranged bulbous, curved, and pointed forms that, when seen from above, form a Surrealist female face. Unlike skateparks, which segregate, the Malmö intervention sought to integrate skaters into the urban fabric and allow them to energize the public space. In Candy Courts (2023), Sablone’s colorful sculptures transform a spot already being used by skaters — a tennis court in Montclair, New Jersey — into a playground- like landscape, while the under-construction Sun Seed is a monolithic sculpture that incorporates a familiar skatepark feature, a “pump track,” which the architect renders as an undulating, bright-red strip. For PIN–UP, fellow skater-designer Jonathan Olivares sat down with Sablone to discuss seeing everything as a surface, skateboarding as an architectural framework, and reclaiming and reinterpreting public space.

Photos by Lee Mary Manning for PIN–UP XXL.

Jonathan Olivares: For a while, you were weekend-warrioring it to Boston to skate, right?

Alexis Sablone: When I was a teen, yeah. I grew up in Connecticut, in a town called Old Saybrook. New Haven was probably the first city I skated in, but there was just more of a scene in Boston. By the time I got there, that was like the era.

And you moved there eventually?

Not til grad school, many years later.

Do you still have a connection with Connecticut?

I opened a skate shop in New Haven a couple years ago.

No shit! I didn’t know that. What’s it called?

It’s called Plush. I designed and built it out.

The interior of Plush, Alexis Sablone’s skate shop in New Haven, Connecticut. Photo courtesy of Alexis Sablone.

That’s so rad! Was there an experience, either in New Haven or Boston, maybe not at the time, but at least in hindsight, where you were like, “That’s when I noticed architecture?”

I mean, New Haven has such a wealth of architects that I still look at and reference today. There’s the Paul Rudolph garage [the Temple Street Garage, 1959–61], and even places like the Knights of Columbus Building [Roche-Dinkeloo, 1969]. I’ve never seen anything like it!

That’s a killer building.

It’s an icon. Such a landmark. Then there’s Marcel Breuer’s Pirelli Building [1970] — we used to skate the stairs on that. And at Yale there are two Louis Kahn projects and the Beinecke, the Rare-Book Library by Gordon Bunshaft [1963].

That’s a pretty great skate spot.

It’s one of the best skate spots in New Haven. We used to look into the sunken Noguchi plaza that’s right there.

You had the best architectural training you could have!

I didn’t realize it at the time, but totally. It was only years later that I was like, Wait, that was a Noguchi?” We just looked down there — you can only access it from within the Beinecke. Jim Greco [the American professional skateboarder] is from West Haven. There was a myth, I don’t know who started it, that he jumped down and kickflipped the pyramid. We could never confirm whether that was true or not. It probably wasn’t. But we used to look down there and talk about all the stuff we would do.

Alexis skates down the Guggenheim's spiraling ramp. Photo Courtesy of Alexis Sablone.

Did you ever go into the library?

Yes, when I was at MIT. We did a field trip to New Haven.

That must have been such an eye-opening thing. My feeling is that skateboarding is a primer in architectural fundamentals: not only are you often dealing with the footprint of these buildings with plazas, you’re experiencing them without the star-struck aspect of like, “Oh, I’m at this Paul Rudolph.” You’re experiencing it as “I’m here fucking with these ledges. I’m fucking with these stairs.” Are there specific details in those spaces that you would know from skating them that other architects or architectural historians wouldn’t be as familiar with?

A skater and an architect are looking at details with different goals in mind, but with an overlapping set of interests. The tectonics or how one thing joins to another are the same questions a skater asks. Like, “Is there a crack? Where’s the joint and can I grind through it?” A lot of Modernist or Brutalist structures can be good for skating because things are at the correct height and made from either high-quality concrete or granite or marble. You want a bench that’s between 10 and 14 inches tall.

You know that height. There’s an intimacy.

The Beinecke ones are kind of high though. But when I was younger I was like, “Well, it’ll push me to learn how to ollie higher.” It’s funny, because, as you were saying, a skater doesn’t approach something with the awe of “Oh, there’s a Noguchi plaza.” There’s a collapse of architectural marvels with an unnamed random curb. We had the Beinecke, and we had this other spot we called “brown wall.” [Laughs]

Photo by Lee Mary Manning for PIN–UP XXL.

Photo by Lee Mary Manning for PIN–UP XXL.

Today, as a designer, where do you find your ideas? How does your design practice fit in with your skating practice?

I have ideas all the time. The hardest thing for me is filtering them and committing to them. I oscillate between a temper tantrum to being pretty good-natured and positive. I’ve had some of the best times skateboarding, but it also brings out some of the worst parts in me. I’m a perfectionist, and there’s no such thing as perfection anywhere, but it’s especially true when my body is my limitation. Sometimes it’s extremely frustrating not being able to do what you imagine you can do. It’s like the opposite of what Marc Johnson said about skateboarding: “If you think you can do it, you can go do it.” I wish that were true. But I feel like that’s true with design.

Absolutely.

At least in theory — I feel like I have no boundaries with design. With skating, I fall so much, and there’s maybe a couple-hour window where your body is intact enough to try to perform what your imagination has thought of hours earlier. Sometimes, at night, you’re like, “I could do this.” You can imagine you can do it. You almost know what it would feel like to do it. And then you get to the spot, and you slam a few times, and it’s rage and frustration and an emotional rollercoaster. When I’m skateboarding, I feel like I’m ten years old again, in terms of maturity. Design for me can also be an emotional process, but in a different way. I have even higher expectations. Maybe my body can’t do something, but I can think through anything and should be able to arrive somewhere that feels right. The initial concept is always more magical-feeling than the worked-out one. Once you’ve actually started to flesh something out, you’re like, “Maybe this isn’t perfect. Maybe this is stupid. Maybe I should start over and I’ll think of something even better.” I do that. It’s important for me, even though it’s painful.

Funny. I’m with Allen Ginsberg when he said, “First thought, best thought.”

A lot of the time that ends up being the case for me. There will be one thing that my brain is just stuck on. Ultimately, it’s undeniable. I can’t fight the idea. It keeps working its way back in, so this must be it.

The AS-1 event celebrated the launch of Sablone’s first signature skateboard sneaker for Converse at the Guggenheim Museum in 2023. Photography by Jutharat Pinyodoonyachet.

Birds eye view of the AS-1 launch installation in the Guggenheim. Rendering of photo courtesy of Alexis Sablone.

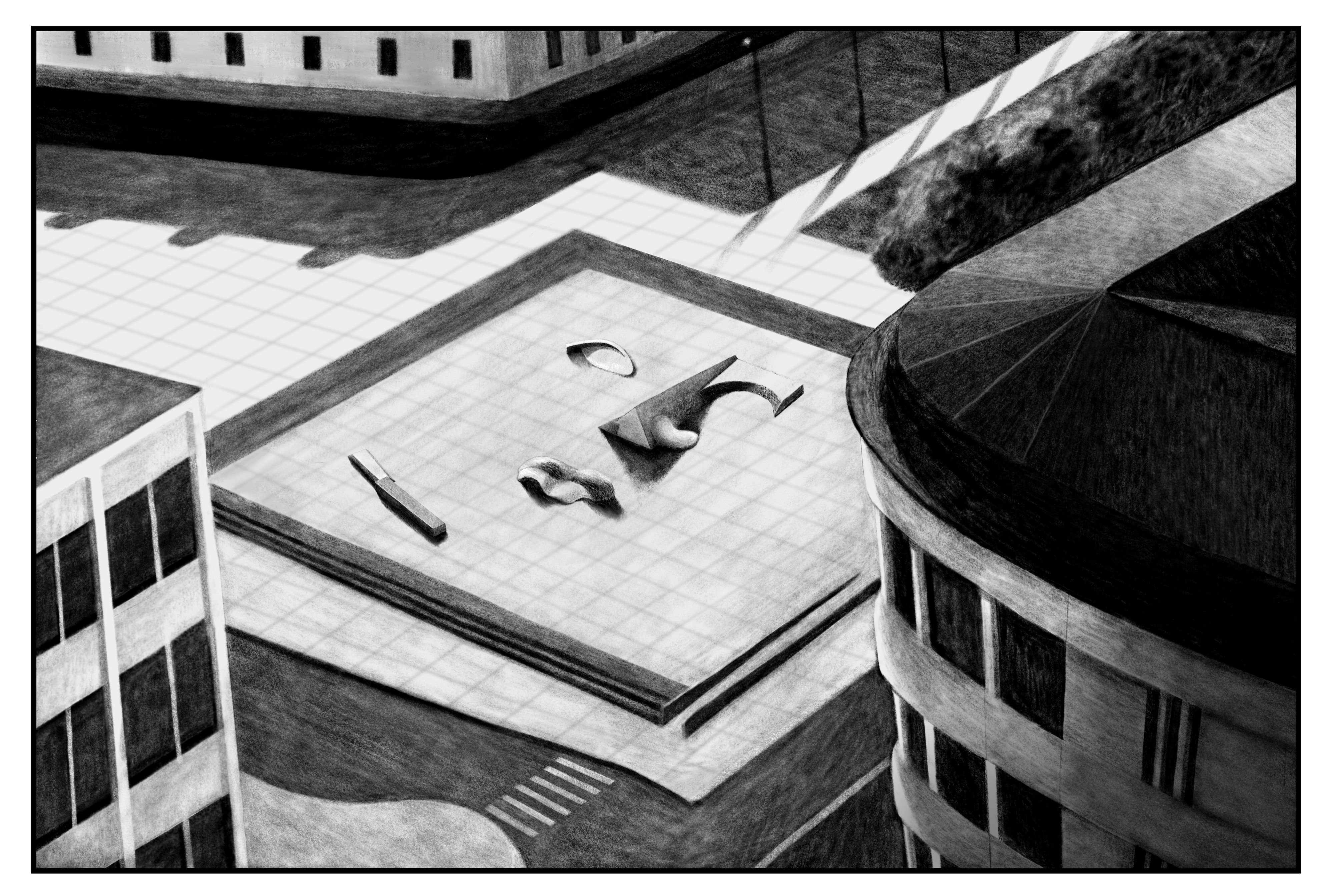

Preliminary illustration of Lady in the Square in Malmö, Sweden courtesy of Alexis Sablone.

When did you start practicing design professionally as a significant part of your livelihood outside of skating?

That probably wasn’t until 2016, after grad school. The first large-scale project I built was in Malmö, Lady in the Square. That almost fell into my lap, around 2017 or 2018 — I got to go there ahead of time and pick out my site, this pristine square. To me it feels like three related but unrelated forms that are in dialogue through the grid lines on the ground.

When we were speaking about the emotions you feel skateboarding versus the ones you feel around design, I was thinking that skateboarding tends to draw in artistic minds because there are no rules, whereas non-artistic minds tend to go toward team sports that have rules. But most of the people I know who skated decades ago are either still skating, which I think is more of an art form than a sport, or they’re doing something artistic like design, architecture, graphics, fine art or dance.

One skill I think skaters either are born with or that is cultivated by skateboarding is the ability to scan your environment and turn its forms back into primitive elements — seeing everything as a surface, so not seeing a stair as a stair or a bench as a bench, but looking for weird slopes and angles to be able to start imagining the possibilities for skateboarding. It’s a constant quest. That’s also why skaters are obsessive — they’ll scan entire cities looking for spots. There’s a restlessness and a constant asking: “What’s beyond that and what’s beyond the beyond?” Embedded in skating is a balance between the physical and the ritual aspect. It’s an iterative process, basically, and there’s a certain amount of patience required.

Driving around searching for spots is so similar to design because it’s a process — thinking about it, scanning, a little bit of research. Then, once at the spot, you’re like, “I’m going to do this thing.” There’s work that goes into it. And half the time, you’re documenting it with a camera. It really is a mirror image of the design process. I also wanted to ask about one of the latest projects you did on a tennis court in Montclair, New Jersey. You’ve taken this approach of laying out objects that bounce off each other or create tension with each other, but you’re also dealing with an existing site.

The project is called Candy Courts. There was already a community of skaters there, using it for a DIY spot. Since there’s a set of courts next door, they were able to keep the DIY, but the original project I was approached for was to replace the DIY, because the city was concerned about safety — splinters, everything falling apart. This approach is much more affordable than building a full-on skatepark. I worked with a group of skaters there and got feedback. Maybe this is a distinction that won’t make sense to most people or will sound snobby, but I don’t think of Candy Courts as a skatepark. It’s a series of sculptures or objects. I think a skatepark is usually trying to prioritize ease of use and flow — an ideal condition with imitation stairs that have the correct rise and run or this and that height of ledge. I didn’t want to be that prescriptive here. I was feeling really inspired by playgrounds. Even though a lot of experimental playground principles might say, “The simpler the object, the more room for imagination,” these sculptures are not simple.

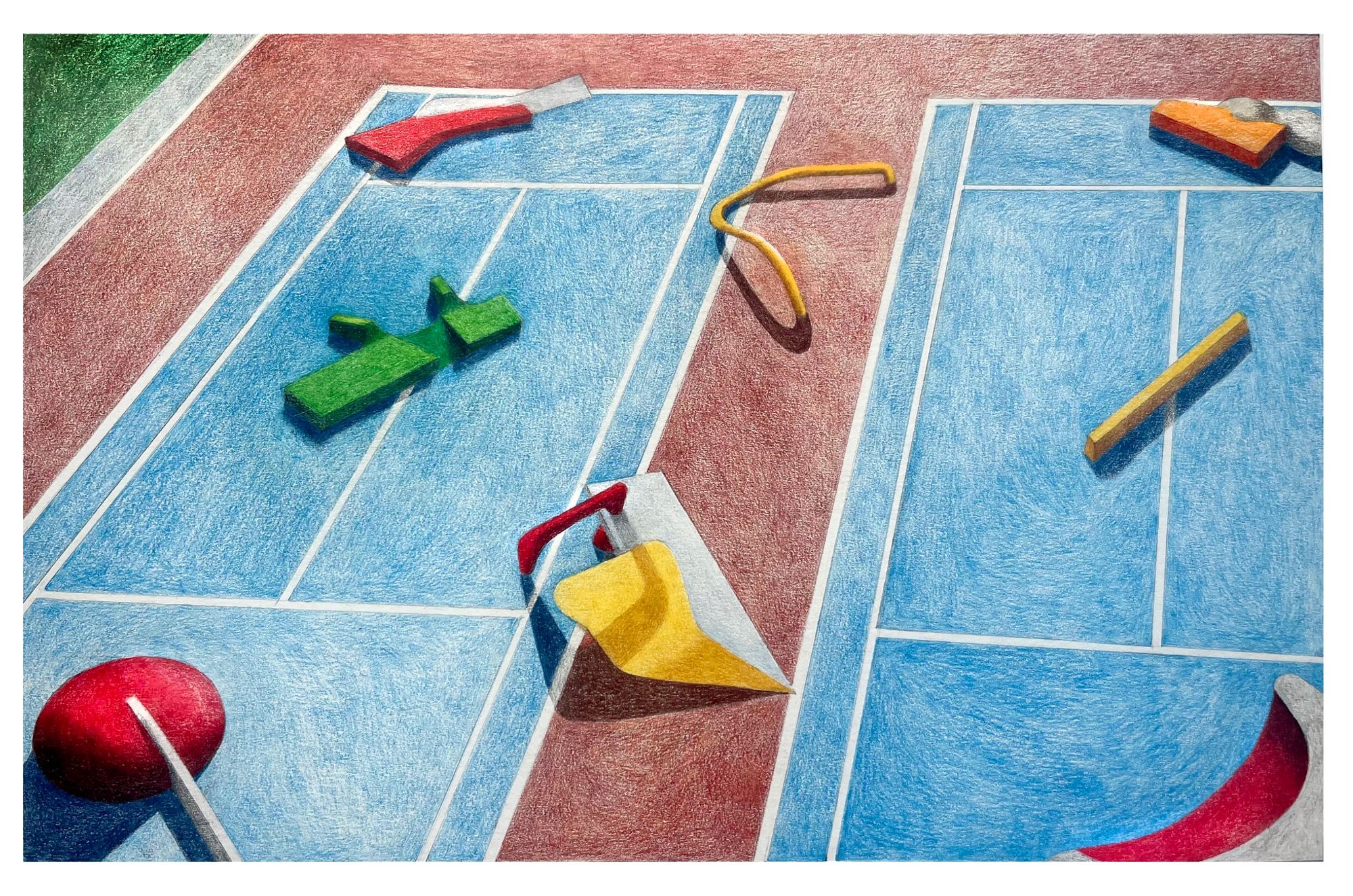

Preliminary illustration of Candy Courts courtesy of Alexis Sablone.

Completed Candy Courts, an installation of sculptures in Montclair, New Jersey. Photo courtesy of Alexis Sablone.

What other projects are you working on right now?

I have one in New Haven that’s in its early planning phases. We’re trying to find funding. It’s a pretty incredible spot under a highway dividing a few different neighborhoods called Mill River. They’re trying to create a better passage for kids to walk home from school to their surrounding neighborhoods. There’s a path along the river. I would really like to try to combine skateable spaces with a playscape or playground, blurring the line between the two.

Some of the best skate spots were absolutely not intended to be skated.

I think that’s something I’ve been wrestling with — what am I doing here designing things for skating, when part of the nature of skateboarding is the reappropriation of space?

It’s inventive.

It’s about seeking out interesting conditions in the city and, even after they’ve been skated by someone else, finding your own interpretation of the same space. That’s a central pillar of skateboarding — it’s what makes it incredible. If I’m designing things for skating, they’re never going to be as cool because I’m doing it with the intention of skating in mind. Does that already ruin it? With Candy Courts, I started to think about the mindset a child brings to seeking opportunities for play, whether in the urban fabric or at a designated playspace. Adults tend to turn that part of their brains off. But I think it’s something that skateboarders continue to do well into their adult years. These forms are unprescribed. It’s unclear what you’re supposed to do with this space. I wanted to make something that felt exciting even to skaters who are used to showing up at the skatepark. I was thinking, “How can I turn the idea of a skatepark on its head, so that it’s not obvious that you can either drop in from this area or that area?”

You sort of choose your own adventure.

In the city you choose your own adventure by seeking out these weird things and figuring out how to skate them. Candy Courts is a collection of sculptures that are like oddities. How do you choose to approach them? There are a bunch of different ways to do it, and they’re not necessarily easy to skate. Some of them are pretty challenging. But street skateboarding is challenging. I wanted to capture that sense of freedom, but keep it challenging, while combining it with this preexisting recreation space.

Personally, I define design as a form of plasticity. Because when you start something, you are basically melting down what things can be. In your mind, things become plastic, then you decide on something and they settle and become stiff again. That’s sort of the basis of architecture. And then someone else is going to come into that space and experience something firm. But if you fuck with it enough, it puts them in a state of plasticity, because they’re like, “What is this?”

That’s the thing that excites me the most and where I’ve arrived at with my own kind of stupid crisis: if skate spots are supposed to be found, and not designed for skating, what can I do as a designer? What can I really bring? I think the answer is I can bring a mindset to excite skaters, while also designing something that can excite non-skateboarders too. I like the idea of large-scale public sculpture and large-scale art that’s all about touching and interacting with your environment. There’s no tape saying “You can’t go there.” It’s like, “Climb on it, lie on it.” Skaters can be challenged, you know? Like, don’t just throw some Netflix in front of someone’s face so they can sit back and watch something easy. Skating is about going out there and doing it.

Miniature of Sun Seed, Alexis's new forthcoming sculpture. Photo by Lee Mary Manning for PIN–UP XXL.

Alexis Sablone working on their chair in Brooklyn, NY. Photo by Lee Mary Manning for PIN–UP XXL.

Pale green patina chair with obelisk legs. Photo by Lee Mary Manning for PIN–UP XXL.

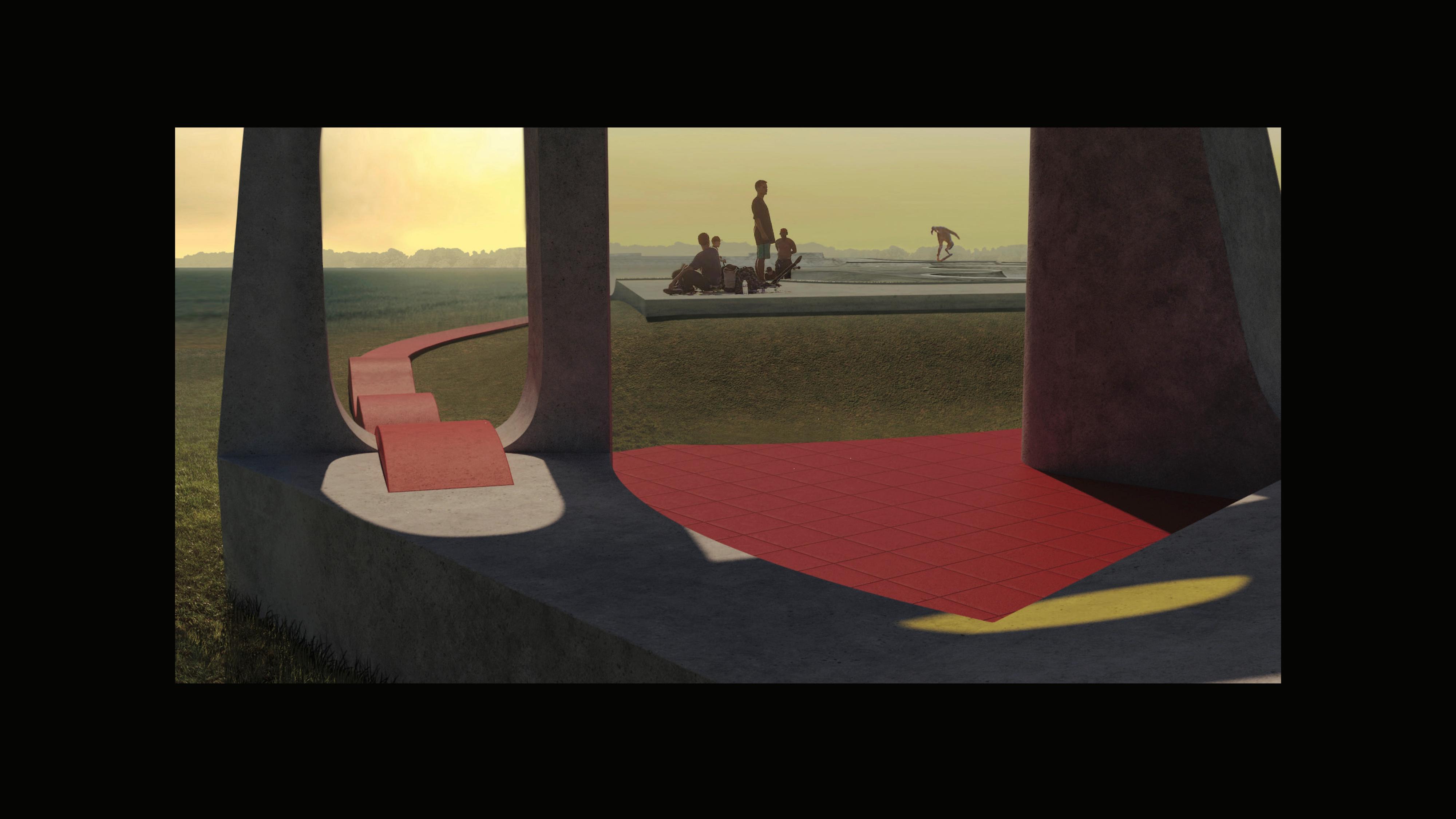

Digital render of Sun Seed courtesy of Alexis Sablone.

Tell me a little bit more about your industrial-design process.

I love drawing. Design for me always starts there. That’s the quickest way for me to try to make sense of an idea — from my brain to paper. But that’s also where I can get caught up, because I can be so precise when I’m drawing. I’ll just draw and draw and draw forever. Then, once I’m actually making something, I feel a lot better. I feel less in my head. So the furniture scale for me is something that’s doable, especially in a New York space. I mean, I had to get a larger studio because you make a chair and then suddenly you better be sitting on it. I want to do more material experimentations. Coming from an architecture background, I’m sometimes scared to be like, “It’s just art.” Because in architecture, you’re so trained to explain the concept and the program, and how it can be recreated and not just be a one-off object. “Can you define the process which would make you able to reproduce this?” I’m trying to figure out ways to experiment and change my process so I’m not always starting from a place of such control. I want to push myself to arrive at things with more spontaneity, to experiment with materials, to allow things not to be final, but rather the first step in a longer process.

It’s in a state of plasticity in a way. You know, Le Corbusier used to wake up every morning and paint before he’d go to the studio. Probably to loosen his mind a little bit.

I think design, for me, is a process that takes a lot of technical ability and iteration, and then intuition on top of that. It’s like what you were describing as something that’s plastic and trying to get down to something more solid. It feels like there’s this pure idea somewhere that I can’t put my finger on. I don’t know what it is, but I know what it’s not. So I start to steer through iteration and iteration, drawing and testing, just steering until my intuition tells me this is the way to get to something that’s buried in your brain that you can’t fully picture. That’s the project.