STREET RELIEF: The Unique Story of Paris’s Public Urinals

Brassaï, Une Vespasienne, Boulevard Auguste Blanqui, 1935; Gelatin silver print. © Estate Brassaï R.M.N. Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts Houston

On a lonely stretch of the Boulevard Arago, silhouetted against the grim rubble-stone walls of the sadistically named Prison de la Santé, stands the last of what was once a quintessentially Parisian feature, in its day as common as the high-tech bus shelters, retro kiosks, and Second-Empire-style advertising columns that currently clutter the French capital’s boulevards. Even more numerous than the then-ubiquitous Wallace fountain, the object in question was commonly referred to — with ironical imperial-Roman grandeur — as a vespasienne; or, in plainer French, a pissoir; or, in yet plainer French, a pissotière; or, in the plainest of English, a cast-iron street urinal. In 1900, during their heyday, Paris counted over 1,500 vespasiennes, in a multitude of different shapes, sizes, and configurations, all enjoying what today might seem a surprising prominence in the streetscape. The author Roger Peyrefitte, in his satirical portrait of post-May-1968 France Des Français (1970), even went so far as to suggest that they were as synonymous with Paris as the Eiffel Tower, citing a French-television interview with Alfred Hitchcock in which the great director was filmed nonsensically slinking round a dowdy brown vespasienne. It was also in this period, when the loosening of morals made public discussion of such subjects acceptable, that Paris’s pissoirs received published homage in the form of Mme le docteur Claude Maillard’s book Les Précieux Edicules: Les Vespasiennes de Paris (1967; the title is a pun on Molière’s Les Précieuses Ridicules), an album of photographs, news clippings, cartoons, engravings, and drawings featuring vespasiennes, accompanying a humorous history of their genesis and development. Les Précieux Edicules was something of a valedictory celebration of its subject, for the street urinal’s days were already numbered: 15 years after its publication, Paris’s pissotières were no more.

Alfred Hitchcock on French television in the 1960s in front of a vespasienne.

Vespasiennes were first introduced by Claude-Philibert de Rambuteau, Préfet de la Seine (and thus de facto mayor of Paris), in 1839, in response to the perennial problem of public pissing that had plagued Paris’s streets for centuries. 18th-century chroniclers recount the horrific stink of stale urine that pervaded the entire city — which must have been truly awful to shock people in an age accustomed to chamber pots in bedrooms and cesspools in cellars — as well as the fate of trees that died in the Palais-Royal gardens from being perpetually pissed on. As Paris’s population exploded in the first half of the 19th century (the million mark was passed in the 1840s), so did the urine issue. Indifferent to monuments and showy spending, Rambuteau preferred to bring practical solutions to pressing problems. His motto “De l’eau, de l’air, de l’ombre!” referred, respectively, to his improvements to the city’s water supply, his attempts to relieve the density of its streets, and his planting of trees to provide shade both for people and horses. He also generalized gas lighting in Paris and worked to enlarge the sewer system. These hygienist improvements came in the wake of the terrible 1832 cholera epidemic (a year before his appointment), which killed 18,000 people. It was therefore only logical that the prefect should attempt to remedy the problem of public peeing.

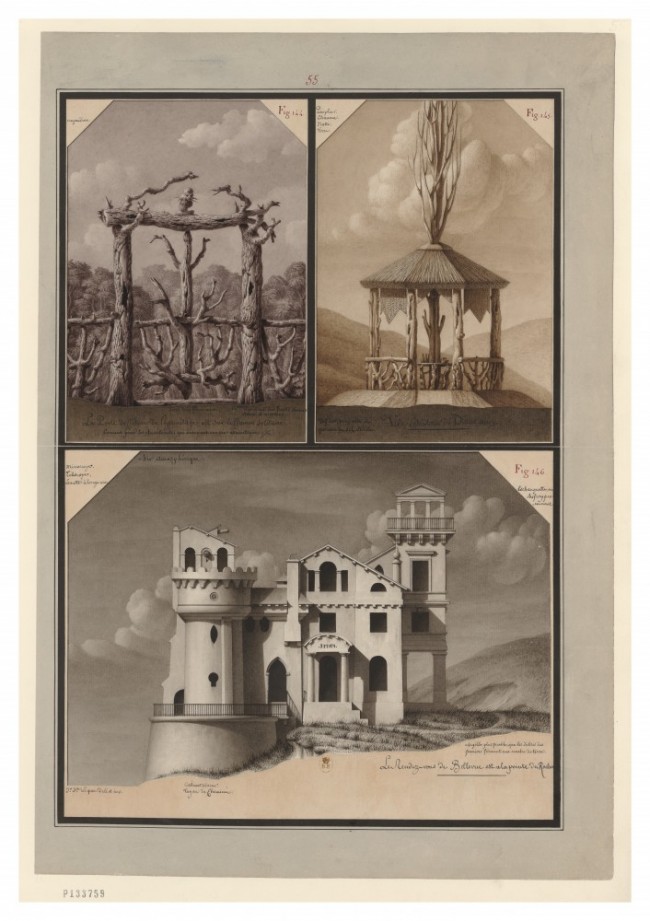

Paris’s first street urinals were one-stall affairs comprising hollow masonry tubes with an entrance cut in one side, a cornice and ball on top, and panels for advertising on the outer surface (somebody had to pay for these new facilities, and advertising revenue, then as now, seemed the ideal solution). By 1843 the city counted over 400 of these “colonnes Rambuteau” as the citizenry nicknamed them. It is said that it was Rambuteau himself, piqued by the association of his name with such a lowly piece of equipment, who invented the alternative term “colonne vespasienne,” in reference to the Roman emperor Vespasian who, in the 70s A.D., had reintroduced a tax on urine, the vectigal urinae, which had first been levied by Nero (urine was collected for use in tanning and as a source of ammonia for laundering). Vespasian event went so far as to have clay pots disposed around the city to be used by the citizenry, so it is easy to see why urinals in France, Italy (vespasiani) and Romania (vespasiene) should bear his name.

A column detail of the pissotière on Boulevard Arago, Paris.

Rambuteau could only go so far in his urban improvements because he did not have the power to get the city into debt. This was not the case for his successor, Baron Haussmann, whose name has become synonymous with the transformation of Paris in the mid-19th century. Most of Haussmann’s interventions were not new ideas — indeed many of them had been put forward under Rambuteau — but what was new was the massive scale on which they were implemented, thanks to the invention of debt financing. With the kilometers of wide new boulevard that Haussmann bashed through the city’s fabric came the need for more and more street furniture, and vespasiennes featured prominently among the new facilities. Bigger, more elaborate, and more efficient models, in cast iron rather than masonry, were produced by the city’s architects, with designs ranging from a bog-standard two-staller to giant six-stall urinals such as the one that lorded it over the Place de la Bourse. To avoid too much clutter on Paris’s pavements, the redesigned pissoirs often doubled up as street lights and/or as illuminated advertising columns, while a new concern for decency saw the addition of perforated screens in front to hide the act within. They shared a family likeness with all the rest of Paris’s street furniture, often featuring scale-covered kiosk-type roofs (influenced by Ottoman garden pavilions, or köşks), and with more or less elaborate detailing — the chicer the quartier, the more elaborate they were — such as the relief-decorated colonnettes on the Boulevard Arago model (whose leafy capitals continue the garden theme). Many of the 19th-century designs survived right up until the end, although more streamlined versions were brought in after World War II.

One of Paris’s last remaining vespasienne in the 7th arrondissement.

When initially introduced under Rambuteau, vespasiennes rather flummoxed some of their first patrons, who were observed urinating on and around them, like dogs at a post, rather than inside them. They were also used in other ways not intended by their designers: as places of sexual interaction between men. As a result, they became a staple of police reports, since policemen frequently made indecency arrests at them, often through entrapment; today these reports constitute one of the few records of 19th-century Parisian homosexual life available to researchers. Analysis of them tells us that, of over 900 arrests for indecency between 1873 and 1879, around a tenth were made at one particular vespasienne near the Café des Ambassadeurs on the Avenue Gabriel — that is to say in the cruising hotspot that was then concentrated in and around the Champs-Elysées gardens — while the six-stall urinal in the Place de la Bourse accounted for over 120 of those arrests. By the early-20th century it was the vespasiennes of Pigalle that had taken precedence in the homosex hierarchy, a prestige they would retain until the end. Slang words developed to describe these tempietti of transgression: cruising in a vespasienne was referred to as “prendre le thé” (taking tea) and the urinal itself became by extension a “théière” (teapot) or tasse (“cup”). Snobbish queens preferred the term “ginette.” As the author André du Dognon (born 1912) explained, when asked whether gay encounters were easier and more spontaneous in the interwar years:

“Infinitely easier! They mostly occurred at the baies. Baies were the same as tasses. We called them that because we had a coded language. The queens from the 16th (arrondissement) wouldn’t say ‘pissotière’ out of snobbery. And there were tasses everywhere in Paris!”

Robert Giraud’s Le Royaume d’Argot (“The Kingdom of Slang,” 1965) informs us that “Celui qui, dans une tasse à trois places, occupe celle du milieu, fait chapelle.” (Literally, “He who, in a three-stall tasse, occupies the middle one, does chapel.”) As Peyrefitte said in Des Français, to hear some homosexuals speak, “one would think Paris had more churches than Rome”! He continued with an imaginary queer conversation where religious terminology is used as code when talking about the disappearance of neighborhood vespasiennes:

“My parish is also ravaged … The Square Baudelaire chapel, which had four stalls, has been razed to the ground; those in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, at Mutualité, and at Metro Cambronne, are just memories. Soon we won’t know where to pray. And to think the Church preaches dialogue! … (The “Chapelle des Apparitions”) has also disappeared, alas! It was the big news last week. In its place you’ll see a pile of sand on which a pious soul has placed a bouquet of artificial violets.”

More prosaically, interviewed for a book on homosexual life in interwar Paris, René Redon (born 1900) replied to the question of where most of his gay encounters occurred:

“In the urinals! That’s all I ever knew! I never set foot in a bathhouse! There were loads of tasses in the Rue de la Chapelle — all that’s been demolished. They operated night and day. If you only knew the people I was able to bring back home! Today I wouldn’t dare.”

In Rambuteau’s era, the smell of a vespasienne was nothing in comparison to the general stink of Paris. By the 1920s, advances in plumbing had made their olfactory assault impossible to ignore: in her autobiographical novel Jigsaw: An Unsentimental Education (1989), Sybille Bedford described the city as she knew it then with its “compound gusts of smells: open pissoirs with tin screens like fire-guards being prominent and numerous.” This was one of the reasons that led to their eventual abolition. Another was of course that they were terribly sexist — where were the ladies supposed to go? (Attempts had been made over the years to introduce chalets de nécessité and lavatories souterraines, but never in sufficient numbers.) And then — and this was no doubt the reason that most moved the male-dominated authorities — there was the incessant corruption of French youth by the flagrant cottaging that went on within their cramped confines. The number of vespasiennes began to diminish in the 1930s, those most in public view being removed and not replaced. This trend continued steadily until, in late 1959, the rightwing-dominated Conseil de Paris voted to phase them out entirely. Their decision provoked such an outcry, however, that it was repealed in early 1961. But nonetheless the slow decline continued. It was the arrival in 1979 of Paris’s first democratically elected mayor — as opposed to the government-appointed prefects who had previously reigned supreme — that settled the question once and for all. That first mayor was Jacques Chirac, and in 1981 his administration voted to remove all the city’s remaining vespasiennes and replace them with fee-charging “Sanisettes” — newfangled, hermetically closed unisex cubicles that automatically washed themselves after use. After pronunciation of the death sentence, execution was swift. In 1984, the photographer Jean-Claude Aubry visited the Parisian suburb of Argenteuil, where, piled up in a field, were the rusting vespasiennes of yore, listing decrepitly like old tombstones. There are rumors that some escaped: one was spotted for sale in the flea market; another apparently serves as a cloakroom in a flamboyant 7th-arrondissement bachelor pad. The Boulevard Arago pissotière, standing as it does in the shadow of Paris’s most notorious prison, is hardly a hub of illicit activity, although it is well frequented by taxi drivers: on a recent afternoon, in the 20 minutes it took to photograph it, more than 15 chauffeurs stopped there. Why did this one vespasienne survive, an administrative anomaly so at odds with the functionary’s usual missionary zeal? Is it because of the presence of the prison, and the consequent fear that road works might provide cover for an escape attempt?

While the vespasienne has disappeared from the sanitized facsimile of yesteryear that constitutes central Paris today, it lives on yet: in old photographs — as well as posing atmospherically in shots by Brassaï and other well-known names, they can be found lurking at the edge of many an anonymous street scene; in film — glimpses can be caught in Peter Ustinov’s Lady L (1965) and the comedy crime flick Les Combinards (1966), while in the satirical Clochemerle (1948), a Beaujolais village decides to ape the capital by installing a pissotière in its main square, much to the consternation of some inhabitants; but most of all in books, for they were distinguished bit players in numerous literary endeavors. And the passages in question are, of course, almost all about cottaging. It therefore comes as no surprise to find a vespasienne in the pages of Proust (La Prisonnière, 1923), nor is one at all astonished to read that it is the flamboyant Baron de Charlus who is spotted inside it. Given the slang in use at the time, the academic Jarrod Hayes has wondered if the many references to taking tea in the pages of Proust might not be interpreted in a less-than-innocent light.

The now omnipresent Sanisette, which was first introduced by then-mayer of Paris, Jacques Chirac, in 1981.

Written some 80 years later, Juan Goytisolo’s satirical novel A Cock-Eyed Comedy (2000) is full of ironical nostalgia for the lost Parisian cottages of his youth. One of his narrators, no doubt inspired by Peyrefitte, sets out to “transcribe his cruising experiences in church language … in order to parody it from within and strip bare its hypocrisy.” After many an encounter with the generously proportioned “sancta sanctorum” of various North-African gentlemen in the “Vespasian tabernacles” of Pigalle, he reflects bitterly on their passing:

“The three-roomed, glass-roofed tabernacles … were felled by a cruel, arbitrary death sentence. Infinite opportunities for worship for apostles of standing and substance suddenly disappeared… May I see those responsible for such vandalism — Giscard, Chirac and the whole gang — burn in the seventh, most horrendous circle of those condemned to Gehenna! I will never recover from their barbaric destruction.”

While for some, Paris’s pissoirs were the sordid backdrop to sometimes dangerous and perhaps depraved delights, for others they were the scene of more innocent joys. Henry Miller seems to have found them a refreshing release from puritanical American mores, if his description in Black Spring (1936) is anything to go by:

“At the Saint-Cloud bridge I come to a full stop. I am in no hurry — I have the whole day to piss away. I put my bicycle in the rack under the tree and go to the urinal to take a leak. It is all gravy, even the urinal. As I stand there looking up at the house fronts, a demure young woman leans out of a window to watch me. How many times have I stood thus in this smiling, gracious world, the sun splashing over me and the birds twittering crazily, and found a woman looking down at me from an open window, her smile crumbling into soft little bits which the birds gather in their beaks and deposit sometimes at the base of a urinal where the water gurgles melodiously and a man comes along with his fly open and pours the steaming contents of his bladder over the dissolving crumbs. Standing thus, with heart and fly and bladder open, I seem to recall every urinal I ever stepped into — all the most pleasant sensations, all the most luxurious memories, as if my brain were a huge divan smothered with cushions and my life one long snooze on a hot, drowsy afternoon. I do not find it so strange that America placed a urinal in the center of the Paris exhibit at Chicago. I think it belongs there and I think it a tribute which the French should appreciate. … And yet, how is a Frenchman to know that one of the first things which strikes the eye of the American visitor, which thrills him, warms him to the very gizzard, is this ubiquitous urinal? How is a Frenchman to know that what impresses the American in looking at a pissotière, or a vespasienne, or whatever you choose to call it, is the fact that he is in the midst of a people who admit to the necessity of peeing now and then and who know also that to piss one has to use a pisser, and that if it is not done publicly it will be done privately, and that it is no more incongruous to piss in the street than underground, where some old derelict can watch you to see that you commit no nuisance.”

Let us leave the last word to an architect, in the person of Henri Sauvage, today chiefly remembered for two Parisian apartment buildings clad in “hygienist” white tiles worthy of the sprucest public lavatory. Writing in 1923, he set out the prosecution’s plea in opposition to Miller’s defense summary and Goytisolo’s devil’s advocacy:

“Oh how wretched are our urinals! Peristyled places of ill repute where one enters only with shame; shells of giant insects, bristling with spines and stings; two- or three-place labyrinths from which filter acrid odors! At night, dulled lanterns of such flickering glow; mousetraps for catching men; lugubrious mausolea full of mystery! Why are you so wretched, oh you urinals?

“Why do you expose to our gaze the catalog of our infirmities, leprosies, sores, and syphilitic wounds? (Sauvage is referring to the prevalence of advertisements for venereal-disease cures posted on Paris’s vespasiennes.) Why lure us with fallacious advertisements for Byrrh (an aperitif that has long since gone out of fashion) with wine from Málaga? Why do you gush troubled waters instead of limpid cascades? Why do you stink so terribly, so terribly? In place of your gloomy ironwork, I dream of a basin of marble, white and pink like a stork, and washed by water perfumed with verbena! In the center, poppies and cornflowers would bloom, like in fields of wheat or barley, where the banality of pee-pee is forgotten in the charm of watering the flowers.

“Oh how wretched are our urinals!”

Text by Andrew Ayers.

Taken from PIN–UP No. 7, Fall Winter 2009/10.