ROMAN RUINS: Post-war Architecture in the Italian Capital

Casa Sperimentale, Fregene (1968–75).

“A student once asked me if it was difficult being an architect in Rome,” recalls Raynaldo Perugini, a jovial 68-year-old academic who, with his Roman pedigree, is uniquely placed to answer that thoughtful question asked in his class. “Rome is where you come to examine architecture, to learn it. To live in it and be influenced by it is a very different story,” he proffers. It is perhaps Rome’s preponderance, her almost overwhelming and incomparable architectural heritage, that Raynaldo is referring to. The difficulty of creating the Roman contemporary is always implicit. This is a city whose very essence seems to constrain it to look not forward, nor even straight ahead, but perennially backward. Modernist Rome, however, does have a rich history, with metaphysical, rationalist, and fascist architectural styles being well attested and increasingly appreciated. But what of post-war Modernism? Perugini could tell us something about that, for the house he owns in Fregene, one of Rome’s swankier seaside communities, is known as the Casa Sperimentale (Experimental House) and was designed by himself and his architect parents Giuseppe Perugini and Uga De Plaisant in 1968–75. A family job, quite literally. With its concrete pods and strange, almost space-age structure, the Casa Sperimentale, even in its sorry current state, is an emblem, a melancholy and beautiful one at that, of Rome’s Modernist heritage.

Casa Sperimentale, Fregene (1968–75).

Italy’s so-called “economic miracle” of the 1950s and 60s is more generally associated with Milan, but the country’s capital also experienced a boom, expanding exponentially in those years. Rome’s post-war residential projects show enormous variety, with palazzine (small apartment blocks) stretching as far as the eye can see in many parts of the city. There are notable examples by architects such as Ugo Luccichenti and the more well-known Luigi Moretti, whose protean output dots many a neighborhood. Recent years have not treated the Italian capital kindly, and a calamitous political and economic situation coupled with intransigent city government has fostered a sense of decline across all aspects of urban life. This is felt most acutely in outlying areas that are home to some of Rome’s most experimental and important Modernist buildings.

Back at his extraordinary house in Fregene, Perugini recalls his father Giuseppe’s avant-garde and really rather radical approach to architecture. In the lead up to, and even during, construction, countless options were drafted and trialed on site. At one point Perugini Sr. envisaged totally sealed habitation units, with no windows. “At this my mother intervened and said that my father was totally mad!”, laughs Raynaldo. Uga and Giuseppe’s experimentally innovative oeuvre was considerable but is largely forgotten or was never built, such as their Centre Pompidou submission featuring four oscillating propeller-like towers bringing exhibitions directly to the visitor, their proposed Roman hospital where patients are delivered to operating theaters in pods, or a proposal to link Sicily to the mainland via a giant rotating wheel. Such paper dreams are perhaps the highlight and the swansong of an era when architects managed to unshackle themselves from the past and look exclusively to the future. In homage to the spirit of those times, PIN–UP sent photographer Camille Vivier to capture six post-war Roman projects that are worthy of celebration and reappraisal before they’re possibly lost forever. Because in the Eternal City, it is modernity itself that is ultimately impermanent.

Casa Sperimentale, Fregene (1968–75)

Detail of Casa Sperimentale, Fregene (1968–75).

Experimental through and through, the house was a family collaboration between husband and wife team Giuseppe Perugini and Uga De Plaisant, assisted by their then 20-year-old son Raynaldo. Perugini intended the house to be infinitely expandable, and consequently devised a reinforced supporting structure onto which concrete parts were clamped: exterior walls, concrete cupboards and shelves, and spherical bathroom pods, all according to the family’s changing requirements. Over the years trespassers and Mother Nature have ravaged this incredible structure, whose restoration the nearly 70-year-old heir is seeking to finance through grants and donations. Here's a video tour.

_________________________________________________

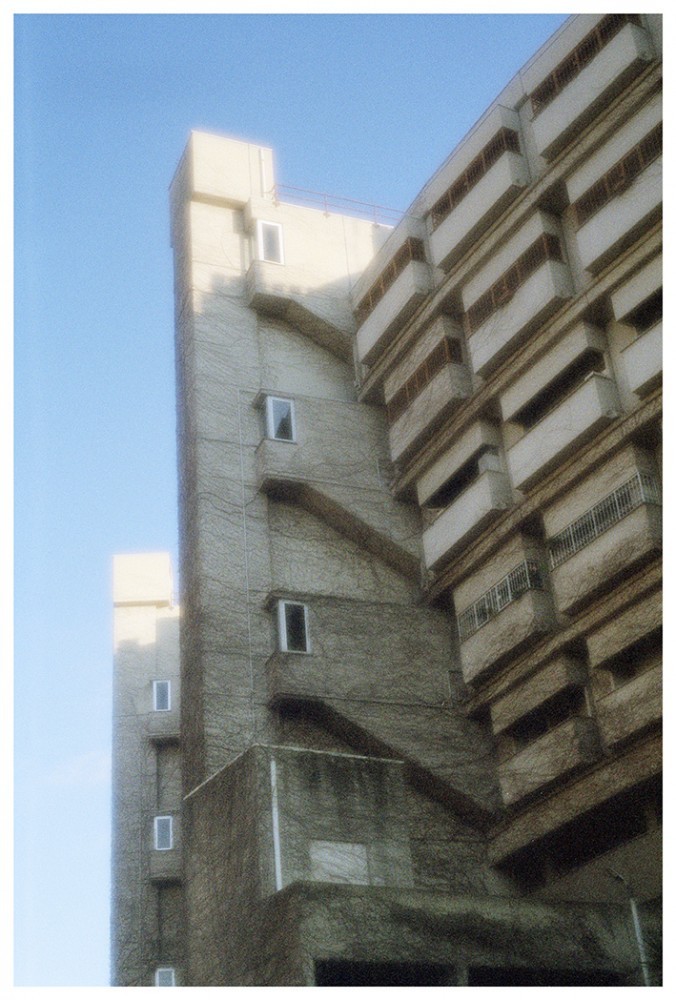

Corviale, Gianicolense (1975–84)

Corviale, Gianicolense (1975–84).

One of Italy’s most controversial social housing projects, the 3,100-foot-long mega-structure — dubbed “il serpentone” (the big snake) — was said to be doomed long before the first stone was laid. The design was coordinated by architect Mario Fiorentino and clearly referenced Le Corbusier’s unité d’habitation, with a service axis and stacked “streets in the sky,” home to over 8,000 residents. Planned in the late 1960s, by the time of its completion in the early 80s the complex was already home to many illegal squatters and remains so to this day. Its exaggerated scale, isolated location, and lack of connection to the city at large ensure that it still stands, like a forgotten ruined aqueduct, only of the inhabited and thoroughly Modern variety.

Corviale, Gianicolense (1975–84).

_________________________________________________

Villa Moravia, Fregene (c. 1966)

Villa Moravia, Fregene (c. 1966).

Standing right where the beach meets the mouth of a river, this solitary structure was built to designs by architect Maurizio Aymonino on the instructions of celebrated novelist Alberto Moravia (author of The Conformist, 1951) to replace his villa that had been washed away by floods in 1965. Despite recommendations from the authorities that he position his retreat on dryer footings, Moravia used his celebrity clout and insisted on this beloved spot, calling it his “refuge for the soul.” Federico Fellini was a fellow Fregene resident and owned his own Modernist villa close by. Sadly this was pulled down in 2006.

_________________________________________________

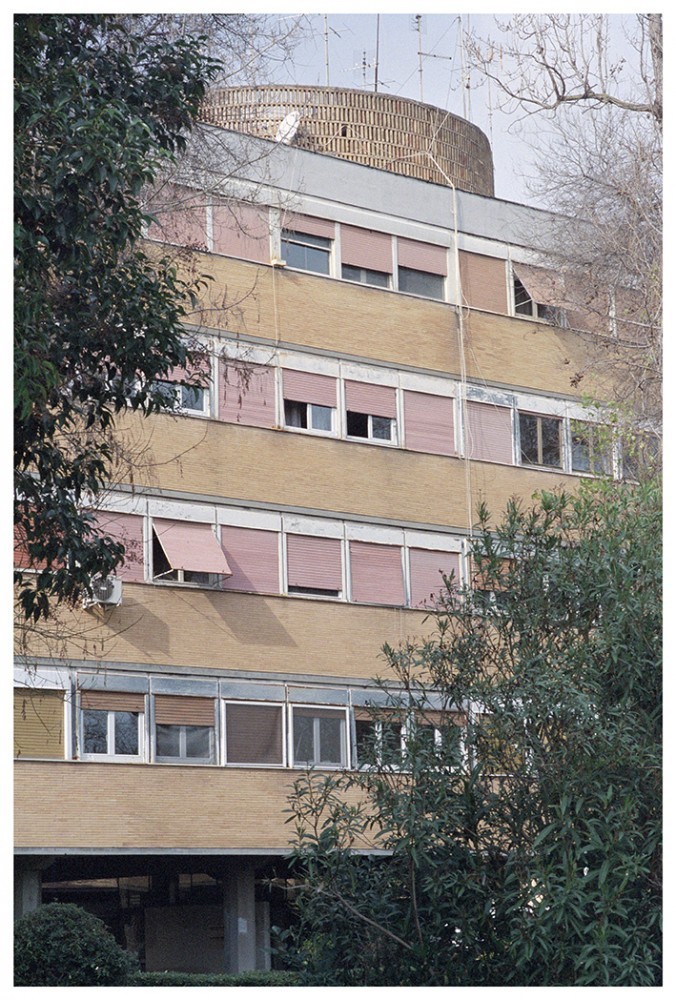

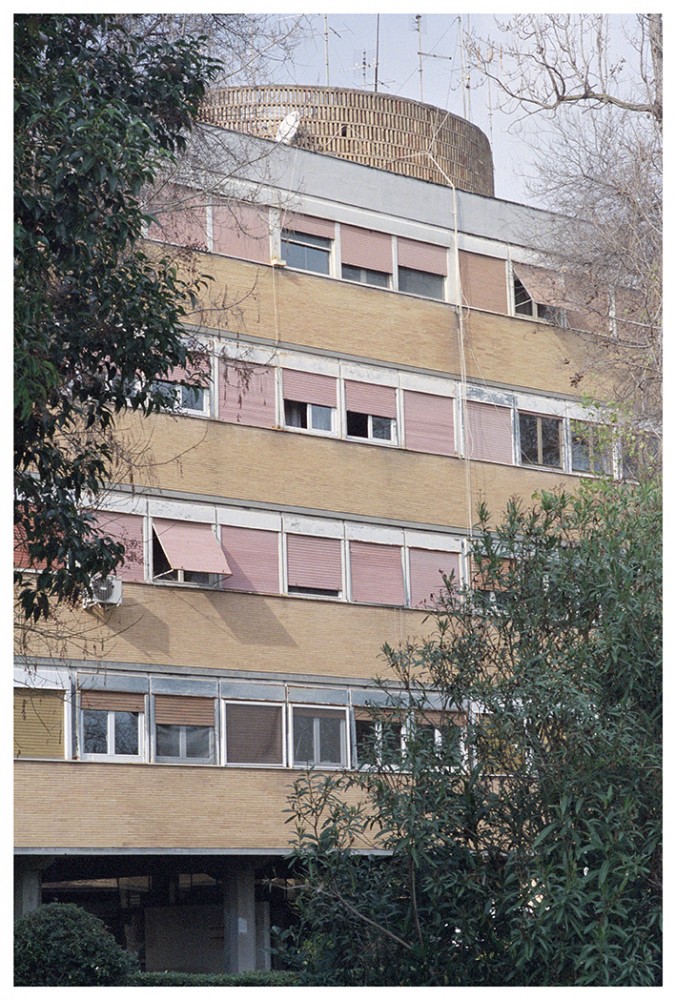

Apartment building, Piazzale Clodio, 62 (1955–58)

Apartment building, Piazzale Clodio, 62 (1955–58).

This palazzina occupies a very prominent position on the nondescript expanse that is the Piazzale Clodio in a middle-class neighborhood in northern Rome. It was designed by the young Luigi Pellegrin, a follower of Frank Lloyd Wright’s who met his master on more than one occasion, including during the American architect’s 1951 visit to Italy. This anomalous residential development seems part Fallingwater and part Soviet Constructivism, with masterfully articulated volumes and external wooden underside paneling that appears particularly ahead of its time. Unfortunately, little maintenance has been carried out since the 1970s, and it shows.

Apartment building, Piazzale Clodio, 62 (1955–58).

_________________________________________________

Palazzetto dello Sport and Villaggio Olimpico (1960)

Palazzetto dello Sport and Villaggio Olimpico (1960).

Built to host the 6,500 athletes who came to Rome for the 1960 Olympic Games, the village’s design and construction were overseen by some of the most prominent architects and engineers of the time. Adalberto Libera (of Casa Malaparte fame) and Luigi Moretti (who went on to design the Watergate complex in Washington D.C.) worked together to create different typologies of residential block. Pier Luigi Nervi engineered the turtle-like Palazzetto dello Sport that served as the Olympic basketball venue. For a long time a no-go area, the opening first of Renzo Piano’s Parco della Musica and then Zaha Hadid’s MAXXI nearby has attracted more appreciative residents — yet most of the village remains in a woeful state of neglect.

Palazzetto dello Sport and Villaggio Olimpico (1960).

_________________________________________________

Circular-formation housing, Via Paolo Barison (1963)

Circular-formation housing, Via Paolo Barison (1963).

From the air, this suburban district of Rome appears to be scared by huge concrete craters. Down on the ground they turn out to be housing clusters constructed during the 1960s building boom. The work of Giuseppe Perugini, who would later go on to design the Casa Sperimentale, the two seven-story, interlocking ensembles were completed in 1963 to house employees of the treasury ministry, and are close to the Roma 70 district, another mid-century satellite town. The wide cylindrical formations are composed of stacked housing units that together create a Modernist Coliseum of sorts, while dead ivy plants have encrusted itself onto their façades like excessive body hair.

Circular-formation housing, Via Paolo Barison (1963).

Text by David Plaisant.

All photography by Camille Vivier.

Art direction by Cameranesi Pompili.

Taken from PIN–UP 24, Spring Summer 2018.