OMAR SOSA’S “COMFORT” SHOW EMBRACES DOMESTIC UNEASE

What’s the price of comfort? For Friedman Benda’s annual guest-curator series, Apartmento’s Omar Sosa goes looking for the receipts, and what he finds won’t put anyone at ease. Comfort, a collection of utilitarian pieces mixed with photographs, sculptures, and paintings, foregrounds objects that seem to embody the concept’s opposite, like Isamu Noguchi’s hot-dipped galvanized steel Pierced Seat and Max Lamb’s Tonalite Boulder Chair #8. Both offer as much pain for their users as pleasure for their viewers, linking the abject to the aesthetic. And yet neither cause that much trouble, in the end, in part because their rarified form makes them inaccessible. Which is to say, you wouldn’t sit in them long, but then, given their status and price, chances are you never could.

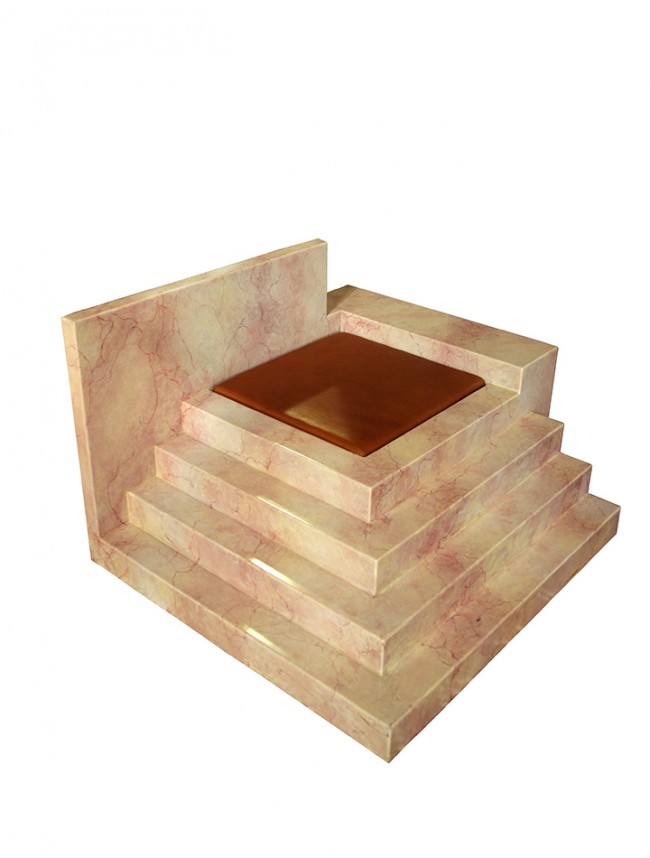

Other selections manifest the negotiations required to make yourself comfortable: Guillermo Santomà’s porcelain plaster and lime Toilet Sink, for example, forces the person at the sink to watch from behind the person on the toilet and, given Sosa’s placement of it in a little nook in full gallery view, the rest of us to watch them both in action. Marijn van der Poll asks us to take a seat by making one, with a hammer transforming a stainless steel cube; Gaetano Pesce swaps the hammer with someone’s butt and the steel with resin soaked fiberglass cloth for his Golgotha Chair, in which form is created by body weight and gravity. Oscar Wilde once wrote, “If Nature had been comfortable, mankind never would have invented architecture.” Or maybe it’s natural to create the uncomfortable.

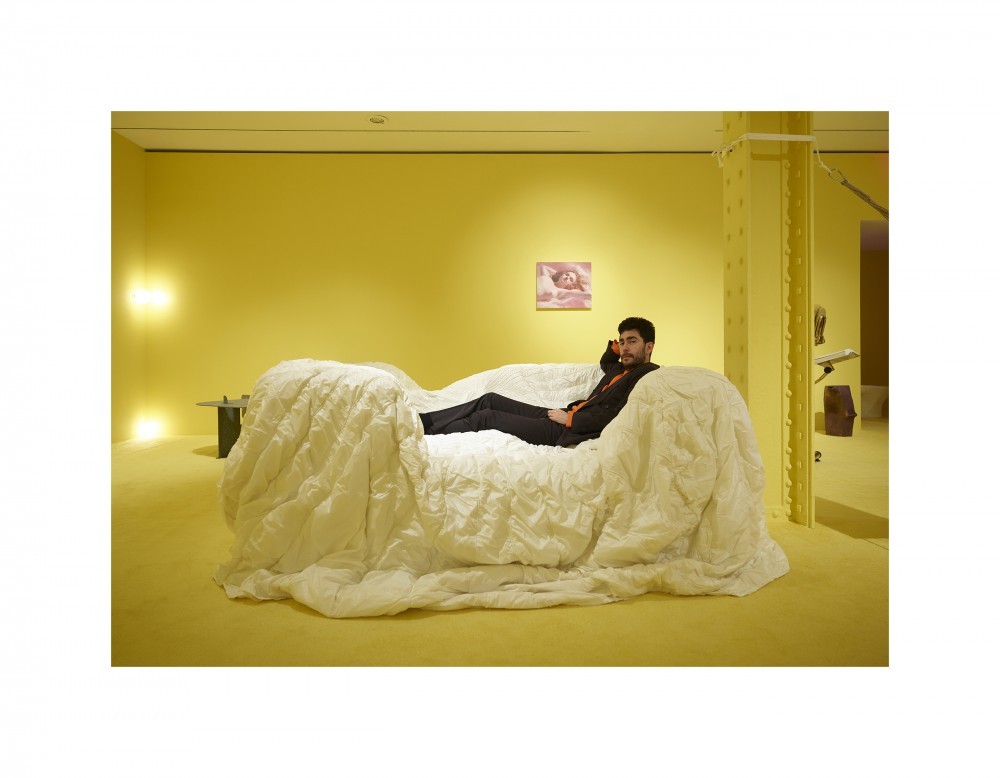

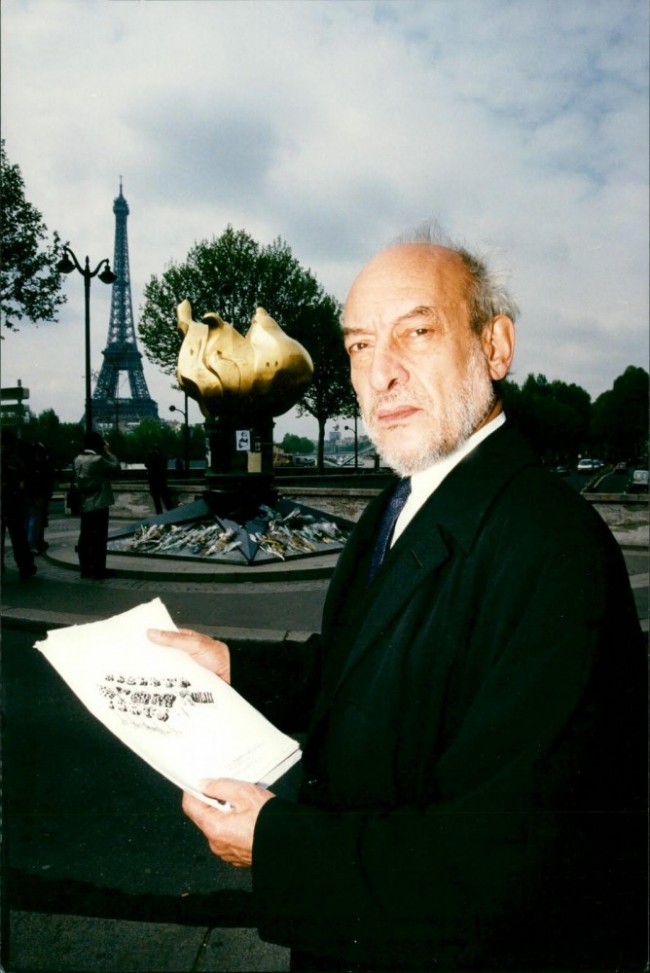

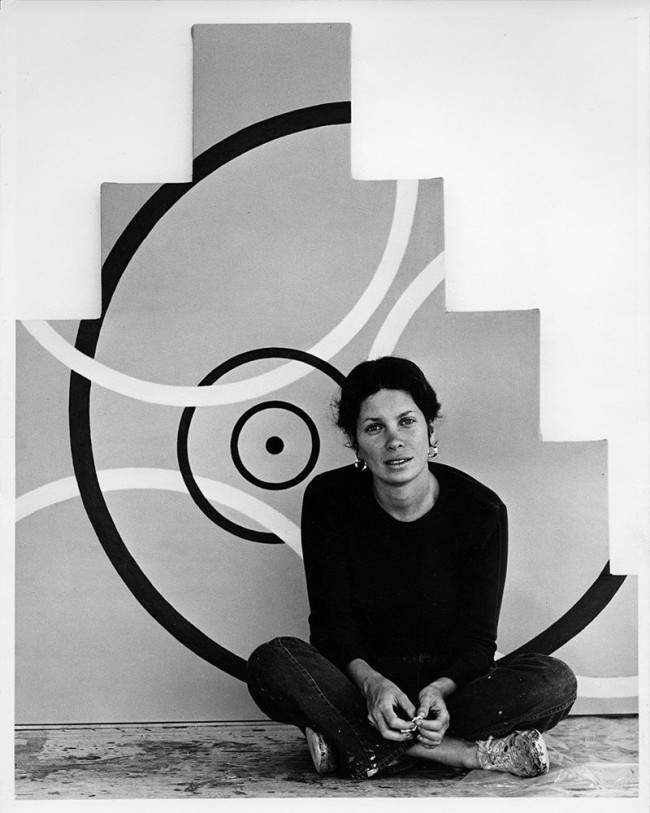

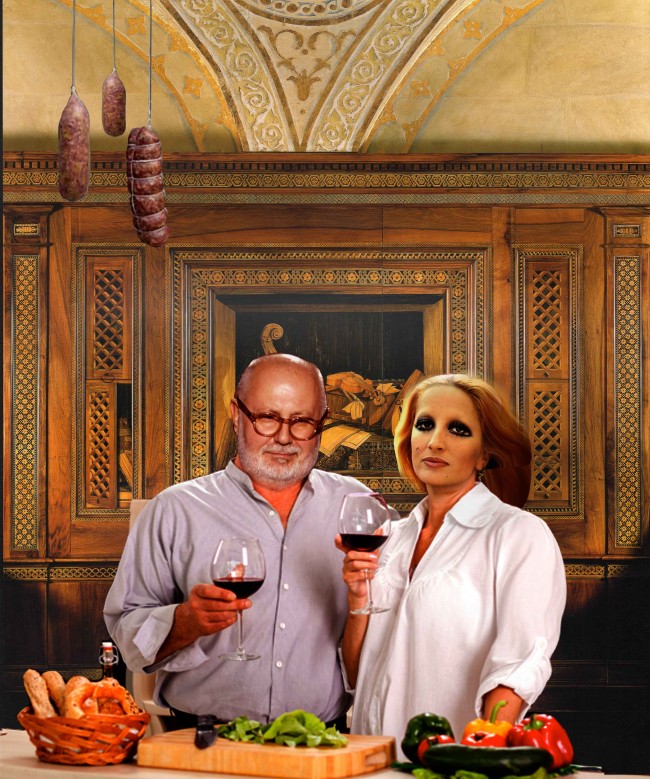

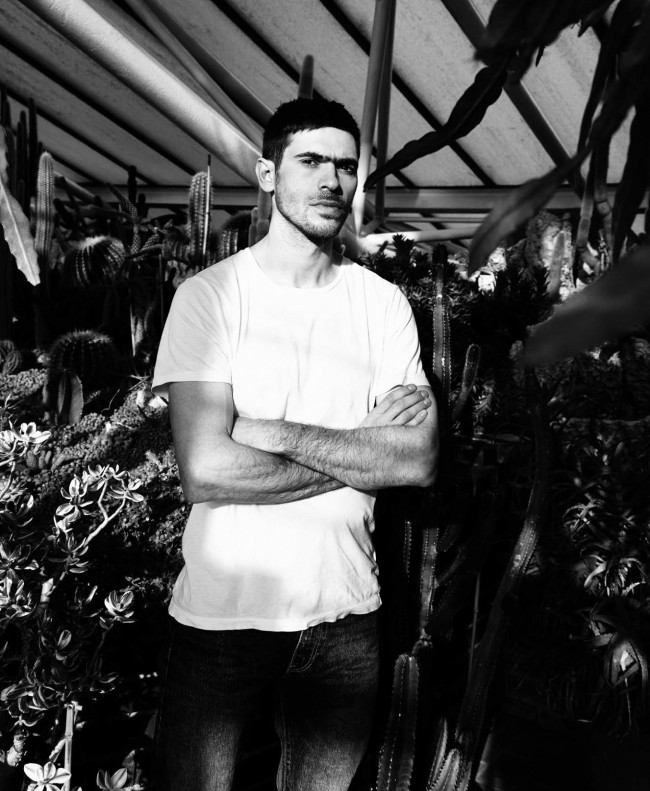

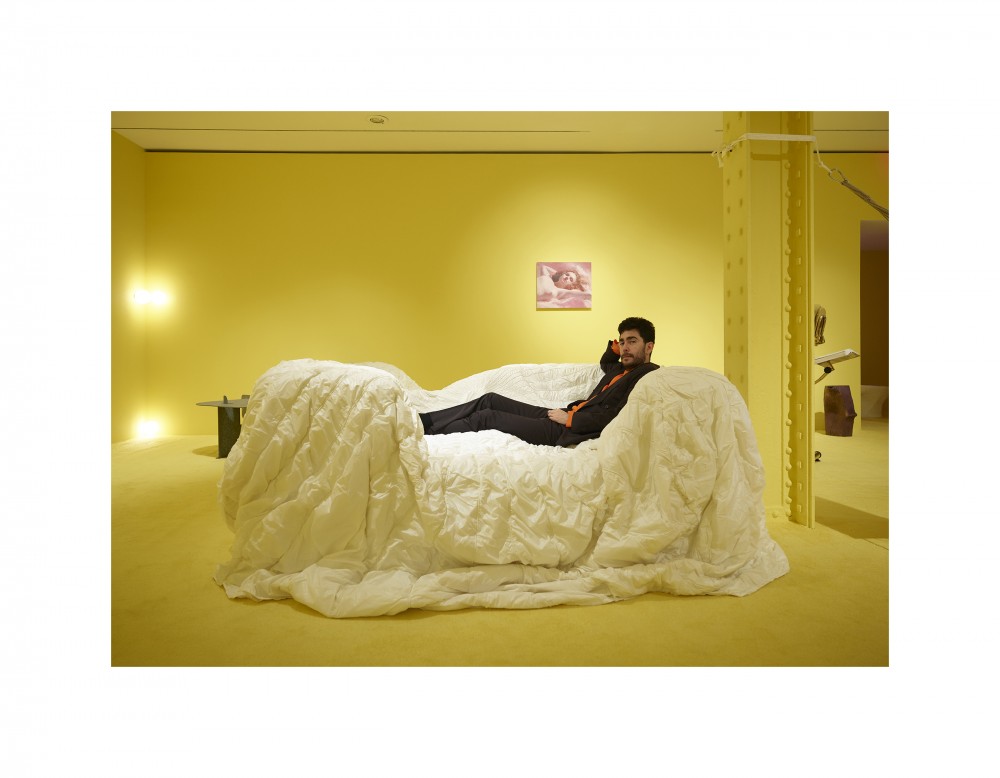

Omar Sosa photographed by Andrew Zuckerman.

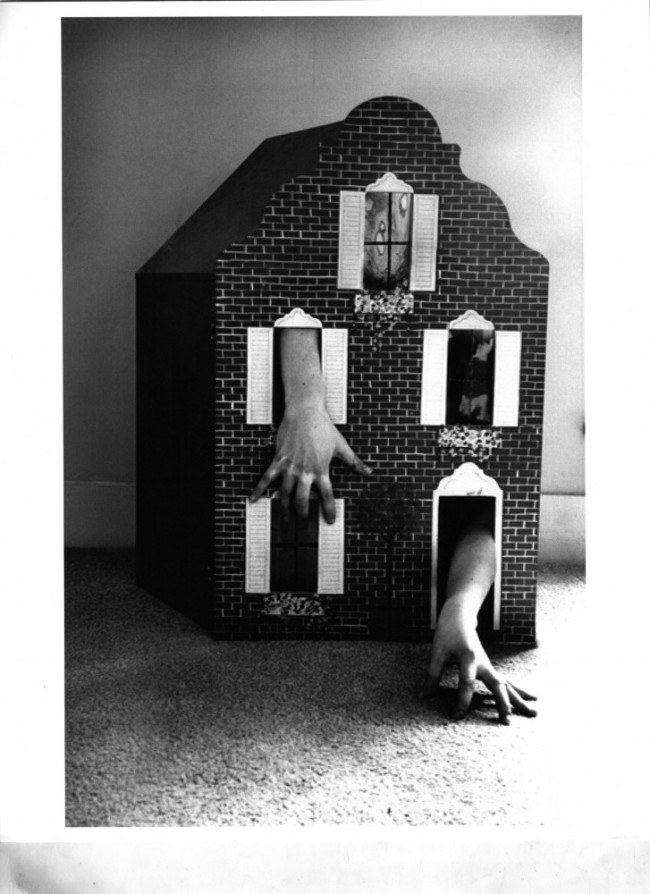

Sosa walked me through the show one eerily warm winter afternoon, pointing out inclusions verging on camp, like BLESS’s No.28 Climate Confusion Assistance, which piles cushy pillows on an even cushier hammock. “That’s what viewers exactly might expect when they visit a show about comfort: a pure, lazy place to crash.” Nicola L’s epic Canapé Homme Geant, a gold vinyl sofa beneath a confusion of cushioned hands and arms, prompted a story of another piece by the French-Moroccan provocateur, her eye-poppingly blue The Giant Foot lounge which Sosa keeps in his apartment and doesn’t always like. “It’s good to stretch your taste,” he told me, and he’s right: if you know just what you like, you’ll never get anywhere new.

And yet, looking at Andrea Zittel’s Linear Sequence #2, which either collapses the distance between Eastern and Western modes of sitting or unites them, depending upon one’s understanding of the difference between assimilation and appropriation, or Ettore Sottsass’s Bookcase No. 18 with its bold blue patina and missing leg, it struck me that comfort zones can swell to accommodate almost anything these days. George Condo’s Smiling Young Woman, installed high above near the entrance “like a gargoyle,” Sosa says, appeared to me blithe, secure in the knowledge that, like Condo’s work itself, what once appeared hideous was now fashionable and might shift again, given time. Just as one person’s pain is another person’s pleasure, the expertly-fitted leather and zippers cossetting the wood face of Nancy Grossman’s Snarl invokes ideas around delineating patriarchy and the assimilation of queer sexuality into the gallery system; it’s a kind of masterpiece, but its shock value, its ability to cause discomfort, is nil in the context of contemporary tragedy and injustice e.g. Trump’s ICE, the Australian inferno, the ongoing massacre of trans women of color. Even Sosa’s most aggressive intervention — coating the gallery walls in a yellow that yolkier than primary, less cautious than a street light, and more or less exactly matches the roll of industrial carpeting across the floors — first gave me a headache, then reminded me of ARO and Sterling Ruby’s similar shading of Calvin Klein’s NYC flagship under Raf Simons a few years ago, and then receded into a kind of invisible status quo. Turns out, the cost of comfort might be the ability to resist it.

-

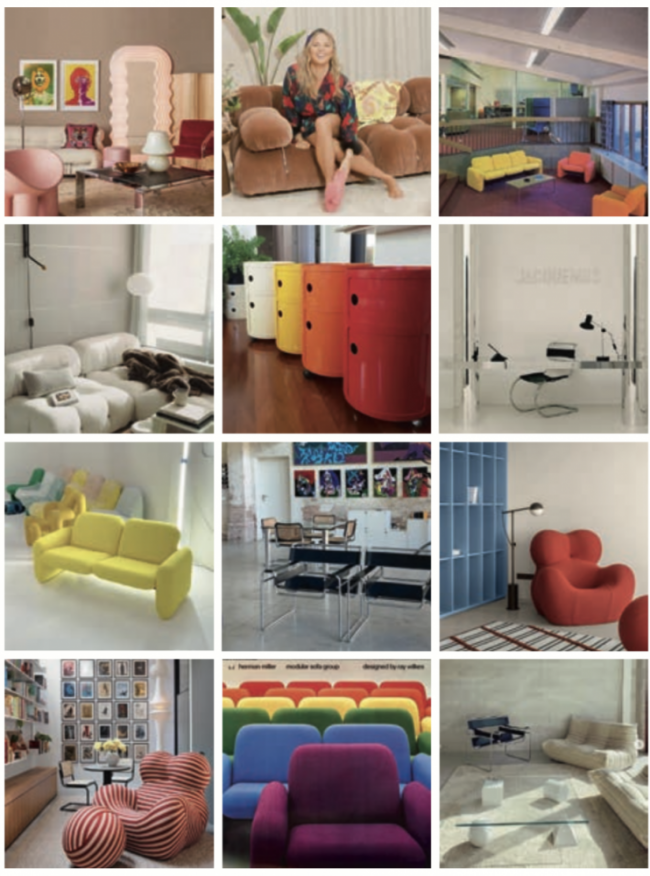

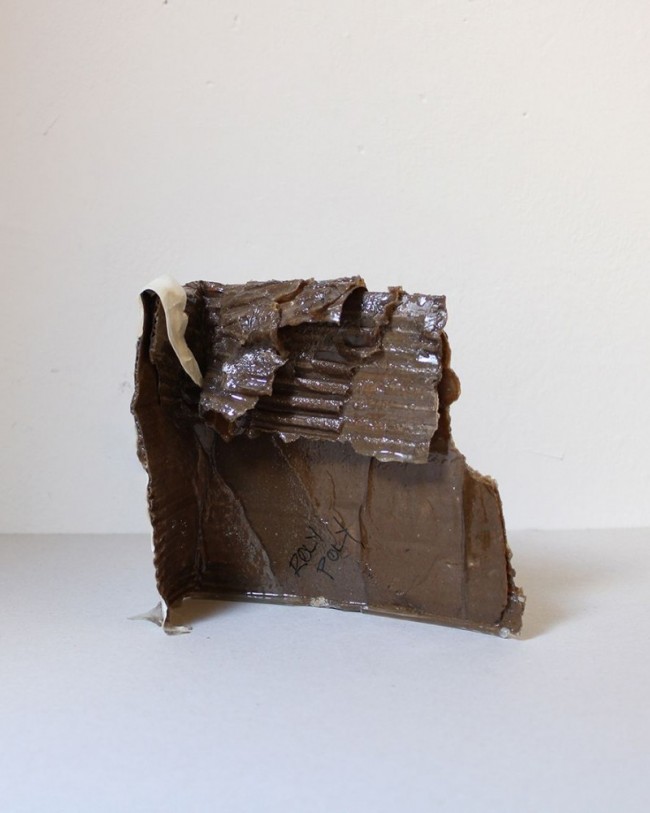

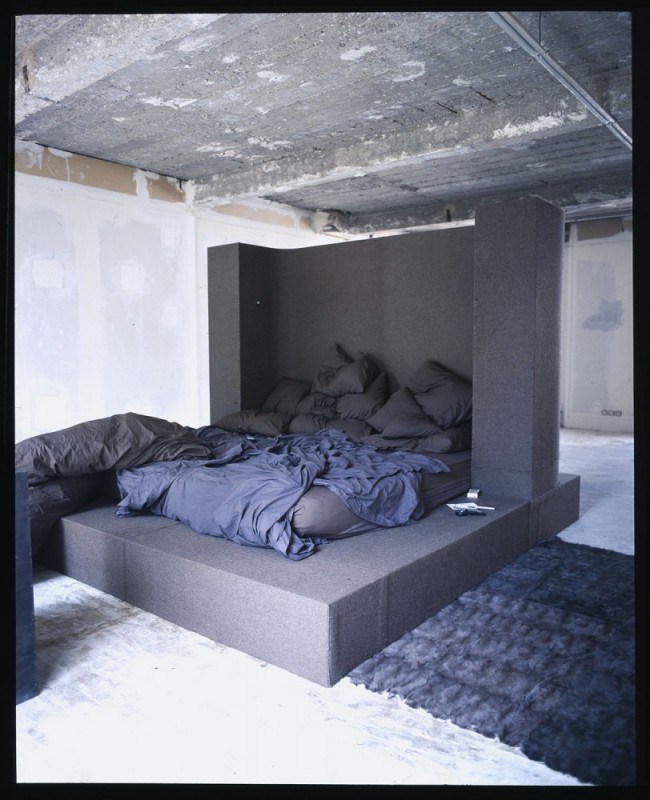

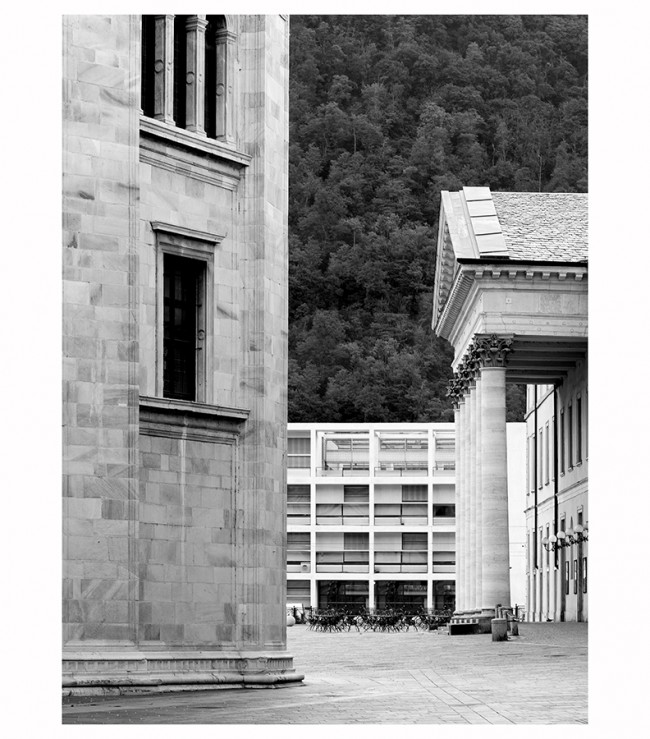

Installation view of Comfort curated by Omar Sosa at Friedman Benda, New York.

-

Installation view of Comfort curated by Omar Sosa at Friedman Benda, New York.

-

Installation view of Comfort curated by Omar Sosa at Friedman Benda, New York.

The irony of an exhibition called Comfort predicated on calculated unease feels especially potent coming from Sosa, who as a co-founder of Apartmento Magazine continues to play a major role in defining contemporary notions of comfort. Given these inherent contradictions, one piece in the show offers a kind of revelation: a small chair, almost maudlin at first glance given its diminutive size and cheery coat of blue paint unfussily applied across its cardboard exterior. A fabric belt above the seat creates tension, especially with Snarl in the periphery. Rocking Chair, made by Adaptive Design Association and painted by Talya Feldman, is not some edgy built-environmental take on BDSM but an actual chair for an actual child, customized so the child can actually use it. I’ll admit the misunderstanding made me uncomfortable. But re-orienting from sensation toward empathy is worth it.

Text by Jesse Dorris.

Installation hotography by Daniel Kukla. Portrait by Andrew Zuckerman. All images courtesy Friedman Benda.

Comfort runs January 9 to February 15, 2020 at Friedman Benda, New York.