DESIGN COLUMN #4: AMIE SIEGEL AND JUDDMENT DAY

Spring 2016, the artist Amie Siegel gave an Artists on Artists talk for the Dia Art Foundation about Donald Judd. And about Judd furniture. All the crossover types were there to watch Amie speak. Simon Castets, director of the Swiss Institute. Cole Akers, from the Philip Johnson Glass House. Curator Alexandra Cunningham Cameron. Artist and architect Susan Horowitz. Design-world denizen turned Dia curator Kelly Kivland was the mistress of ceremonies.

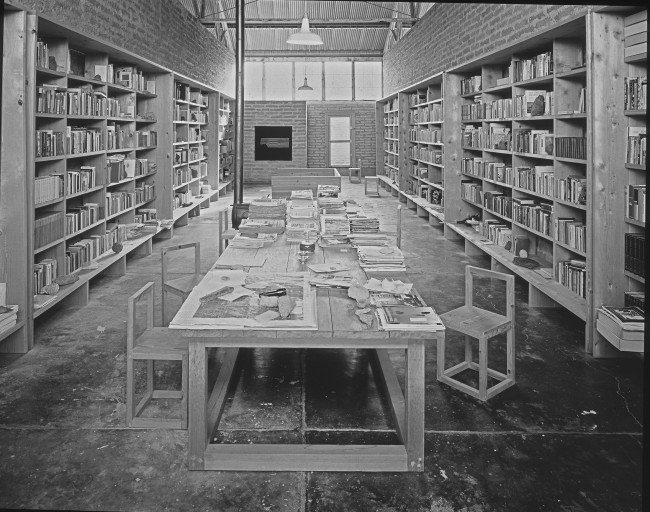

The talk began with a scene from the 1986 film 9 1/2 Weeks in which Kim Basinger pleasures herself while viewing slides of flaccid artworks in the basement of a SoHo gallery. The location of the gallery was 101 Spring Street, a five-story cast-iron building designed by Nicholas Whyte in the late 19th century, which Judd had purchased in 1968 and used as a residence until his death in 1994. (Recently restored, 101 Spring Street now houses the Judd Foundation.)

The scene and its surprise setting (the late artist’s hallowed halls) was the first of many intimate moments of Siegel’s exposé, during which the Judd we thought we knew was transformed by the evidence of his appetite for material culture. Siegel brought us closer to Judd through his obsessions with craft, design, decorative objects, and architecture. At a small dinner after the talk, Andy Stillpass, the art world’s king of inspired commissions, dubbed Judd the “Last Sustainable Dandy.”

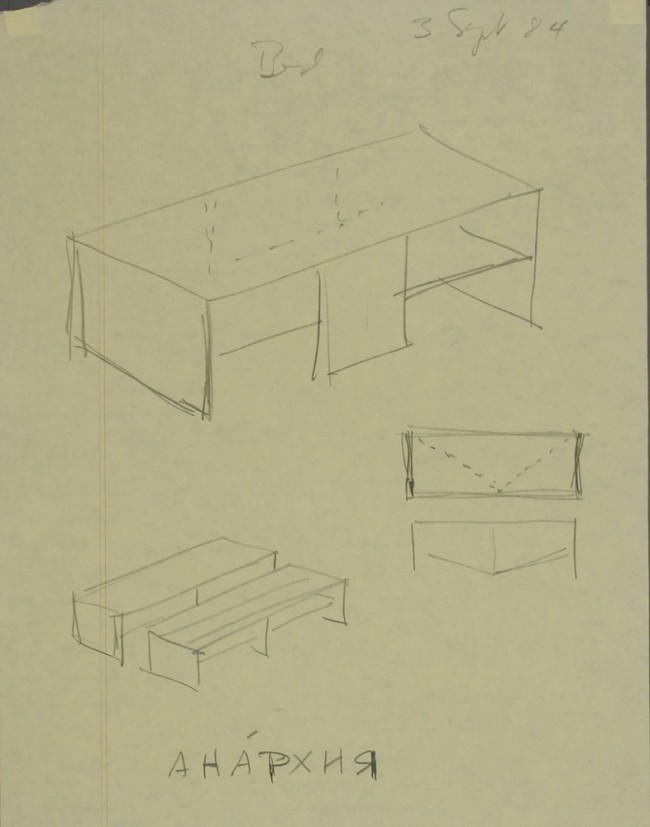

Did you know, for example, that the extent of Judd’s personal collection of objets was phenomenal? Bischofberger level! His archive littered with invoices. Throughout his lifetime he acquired duplicates, even triplicates, of objects he loved. Mexican bowls. Arrowheads. African textiles. Aalto chairs. He placed them in his collection of homes on his puzzle-piece parcels of land, surrounding himself with the forms he admired to better study them, to be shaped by them.

Or that in 1992 Peter Noever commissioned Judd to redesign the Baroque Rococo Classicism gallery for the MAK’s Permanent Collection in Vienna? Although uneasy with the idea of creating an “artificial” installation of furniture in a museum, he skillfully positioned the collection’s crown jewel, the Dubsky Palace’s “Porcelain Cabinet,” in the center of the room, swathing the volume and gallery walls in sharp white to accentuate the sensuous antiques. He made one work for this intervention: his only vitrine. Judd billed the museum as an architect.

Or that sculptor Scott Burton threw a stone through the window of 101 Spring Street in the 1980s? The legend tells as follows: Judd publishes Specific Objects. Burton is influenced and starts making work that straddles furniture and sculpture. Then Judd starts making his own furniture. Competitive animosity? Ask Max Protetch.

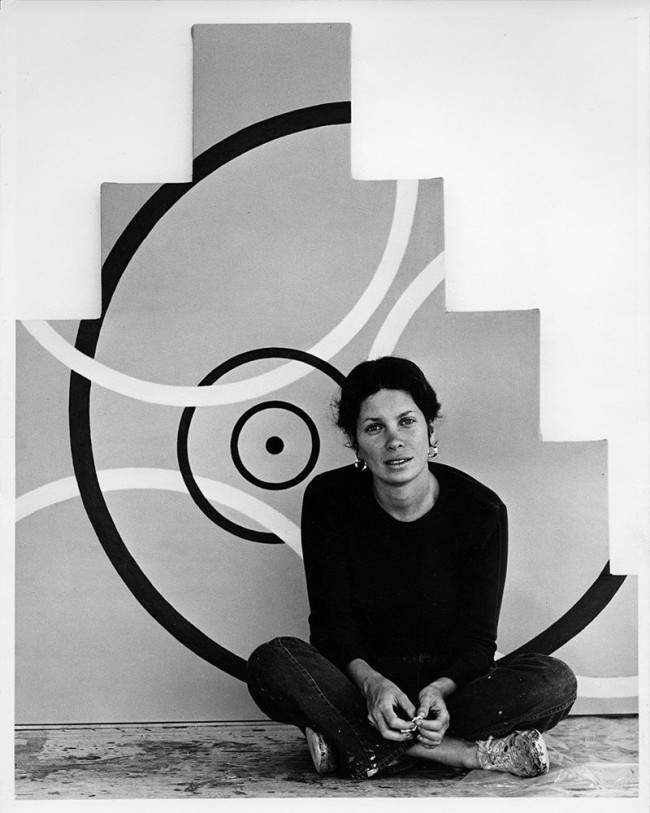

The talk was gorgeous. It was genius. It was messy. And it made us like Judd more. Or just plain like him. And even though Siegel made the point of distinguishing this talk from her own art practice, her work is like this: employing architecture, objects and situations to tell a human story, using an extensive set of media to level reliable and unreliable narratives, revealing the inconsistent truths at the root of our myths.

Seeing Siegel’s work is a like watching your parents kiss: the tenderness, beauty, voyeurism, and that feeling of uneasy familiarity that makes you ponder your own insecurities.

See as much of Siegel’s work as you can. Her spring 2016 show at Simon Preston Gallery called The Spear in the Stone included a piece called Fetish which captures the painstaking yearly cleaning of Sigmund Freud’s possessions at the Freud Museum in London. And Double Negative, consisted of two silent, black and white 16mm films and a color HD video, which features Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye near Paris and its more recent Australian doppelgänger, rendered entirely in black. Need Pepa say more?

Truly Yours,

Pepa

Pepa Shores is a trusted aesthete and design doyenne who irregularly pens reports for PIN–UP from her various travels around the world.