INTERVIEW: Piero Gandini on why the Design Industry Needs to Stop being Bourgeois

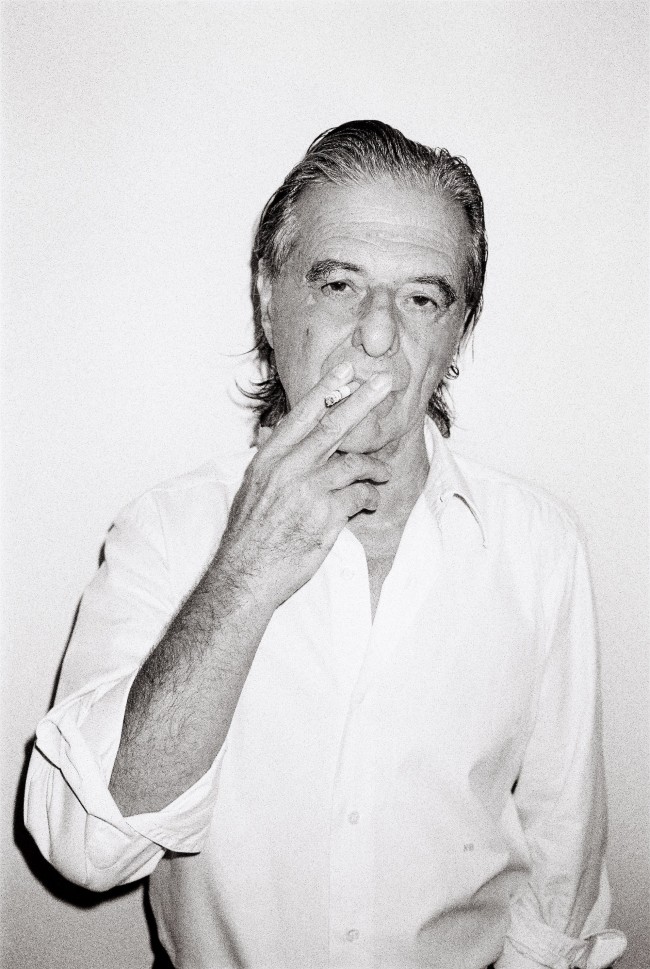

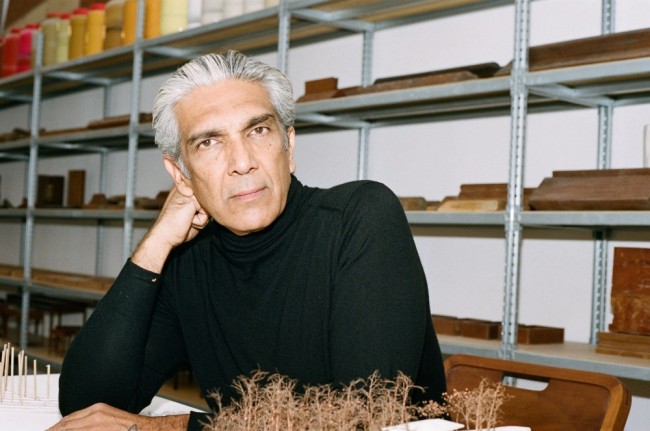

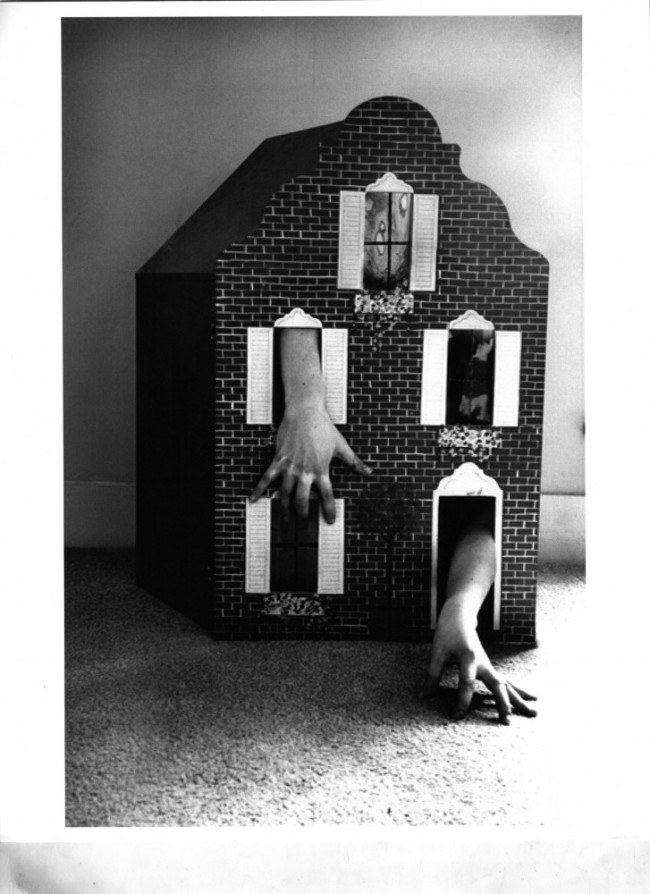

Piero Gandini photographed by Josep Fonti for PIN–UP.

When, in April 2019, Piero Gandini abruptly walked away from his position as president of FLOS, the design world was aghast. He had become something of a ringleader in the tight-knit Milan design scene, not least because he turned the design company inherited from his father from a successful medium-sized business into a 300-million-dollar design powerhouse. FLOS had long been a home for avant-garde talent (Italian bigshots like Mario Bellini, the Castiglioni brothers, and Tobia Scarpa come to mind), and Gandini Jr. continued to welcome innovation, giving some of today’s most sought-after designers their first commercial break — Starck, Urquiola, Anastassiades, Grcic, and, more recently, Formafantasma, to name but a few. He also paved the way for what is now Design Holding, the joint venture that includes FLOS, B&B Italia, and Danish lighting manufacturer Louis Poulsen. When he stepped down, he also left behind an increasingly corporate design industry environment that he himself helped create. Relieved from the grind of running a multimillion-dollar company, Gandini struck an upbeat yet reflective tone when PIN–UP asked him to philosophize about the past, the present, and the possible future.

Felix Burrichter: You started working in the family company in 1989. You left in 2019. How has the design industry changed during those 30 years?

Piero Gandini: My generation was a very privileged generation. We were fully free in a certain sense. We didn’t live through a war. We didn’t live through a big economic crisis, especially in Italy. The country was growing like crazy. It’s a beautiful country with a lot of culture, and most of the economic dynamics were driven by the family, and by family companies like FLOS. So it was a kind of world that was very open and at the same time it felt safe. And because it felt safe, it gave us the feeling that everything was possible, it gave us the ability to take risks. Today the world is much more complicated, much faster, but also much more open-minded. The new possibilities for creativity and interacting with people are enormous. I hope the Italian design world will take some chances to remain a game changer, and not rest too much on its market leadership laurels. I hope they won’t remain in this comfortable bed they’ve made for themselves, because that is very risky, in my opinion. It is not innovative.

You’re talking about risk-taking versus complacency?

What is risky? If we set off in a boat towards the horizon it’s risky, but we are probably looking for something new. If you’re lucky, you find a new land. If you always stay in your room, it doesn’t look risky, but it is because you don’t see what’s happening. While others discover new land you're still stuck in your room. When the Italian design boom began, in the 1950s, and for many years afterwards, the home was the social epicenter for everybody. After all the trauma and destruction of the war, to finally have a house, to have a sense of comfort, and to have safety and a family was central. And there was an industrial revolution, new technologies, so the way you were producing a chair, a lamp, or a sofa was revolutionary and inspiring social progress. It was redesigning the way people were living every day. Today, society centers on many other things: communication technology, technology that has a tremendous impact on how people live and interact. What’s happening with the home continues to be important, but it’s not what captures the imagination of people everyday. So now what do you do? Don’t tell me that your most important concern is your new sofa for the next Milan fair presented in a super slinky picture of a bourgeois apartment at a moment when — Covid tragedy apart — economic inequality and pollution are growing like never before. Because at that point, Enzo Mari will kick your ass and Achille Castiglioni will roll over in his grave. I knew all of those guys. Even the less radical ones, like Vico Magistretti, who was a very elegant designer. He would find today’s attitude in the design world pretty decadent.

Do you think this neo-bourgeois aesthetic is related to a general sense of uncertainty in the world and a longing for a certain status that actually very few can afford anymore? People just want to feel safe, cushioned, pretty, and rich?

Maybe. But we have to avoid being bourgeois. The phenomenon of 20th-century design in general and the Italian post-war era in particular was driven by the utopian idea of bringing nice things to everybody, not for just for a few, very select people. It was the absolute opposite of that. Of course big social problems always existed and design always has just produced home objects, but my personal feeling is that the sense of participation to the big dynamics in the world was much stronger before. It seems to me that the sense of participation is no longer the first priority; it comes way after the color selection for the sofa or the right picture for social media. I know that it’s safe. I know that is the way we make money. I know most expensive houses are in a certain sense bourgeois by definition. But we have to avoid doing that, because if we don’t become militant again we will be not ready for what’s coming. There needs to be another super-creative movement in design, especially in Italy.

But how do you even foster new talent in an era of corporate conglomerates?

Keep your eyes open. Keep your heart open. Studio Formafantasma, for example: I visited them years ago, they were incredibly young and talented. We agreed to wait some time, but then their first industrial project was with FLOS. I found Michael Anastassiades because I saw one of his self-made pieces pieces hanging in the back of a gallery in New York. If you want to do it all by scrolling on Instagram, forget about it. I don’t believe in that. I’m a very emphatic person. I’m crazy about details, so I always want to go where a designer lives. To me, the way they put their shoes on the floor tells you something about the designer. What kind of art they have, or don’t have, or the food they cook, or where they live. I don’t have a standard they have to meet, but I care if there is an identity, a strong identity. You can perceive much better if you are in their world. I strongly believe in values, but also in blood, in vibes, in personal vibes, sharing things.

Is that why you were known to ask designers to sign exclusivity agreements?

Yes. Because if you share such an adventure, such a radical attitude, you have to put everything you have on the table. I offered the possibility of trying, the possibility of making mistakes. My team and I were always there, ready to try, to invest, to see, to discuss. Then there could be a no at the end of the process, but it would never be a conservative attitude. Sometimes you spend years trying without a result. With Jasper Morrisson we spent four years working together before the first light came out. The point is that in every company, in every human activity, but especially in design, if the creative energy isn’t pure and wild you’re no longer an avant-garde company. That’s the only reason we’re out there, to create something the other kind of animals cannot create.

Piero Gandini photographed by Josep Fonti for PIN–UP.

What is your advice to young designers working with companies that may not share these values?

Escape. Find the company that supports you. I know that life is tough. I know you have to pay your bills, and that making some concessions is part of life. But, as a designer, never sell your vision. Don’t do it. It doesn’t help. It’s like when you spoil a kid. It’s easier, but the kid will be weaker over time because he’s just a spoiled guy. So it’s tougher to educate the client. Of course, it’s much tougher to resist the money, but in the end you will be much stronger.

So if you were in your 20s today, would you start a design company?

Yes.

A lighting company?

Oh, even a furnishing one! But I prefer accessories because they’re more flexible, and you’re not obliged to create this vocabulary of interior styling — you can go straight to the product. That gives a much more radical potential than something like a shelf system or a sofa. And they’re better for e-commerce. I’m not saying that the Internet is the solution, because the Internet is a big mess and it also creates a lot of problems. But, back in the 1970s, or 80s, even if you had a fabulous product, the biggest problem you had was distribution. It’s still a big problem today, but now you can play lots of parallel games. The way you sell, the way you communicate with journalists, with clients… So if you’re 28 and you ask me if you should start a furniture company, I say, yes! The potential is there. But you have to have a radical vision and approach. You can’t be too smooth. I don’t believe in a smooth approach, I believe in smart approach. You can be very smart in the way you present a radical approach. Today there is too much smoothness.

So what kind of company are you planning for the future?

Good question. I want to find a way where my participation and contribution is less comfortable for me. I fought very hard to do what I did. And there were some things that were not given. But I always swam in my pool. There were times when the water was too cold, or too hot, or there were too many people in the pool, or the water level was down. But it was always my pool. Now is the time to find another pool, a different shape, different water.

So you have the itch to come out of retirement?

I always had two dreams in my life. One was to produce a movie, and the other was to have a nightclub. So let’s see. In Italian we say l’occasione fa l’uomo ladro — opportunity makes the thief.

Interview by Felix Burrichter.

Portraits by Josep Fonti.

A version of this interview was originally published in PIN–UP 29, Fall Winter 2020/21.