RECONSTRUCTIONS PORTRAIT: Olalekan Jeyifous on Architecture as Speculation

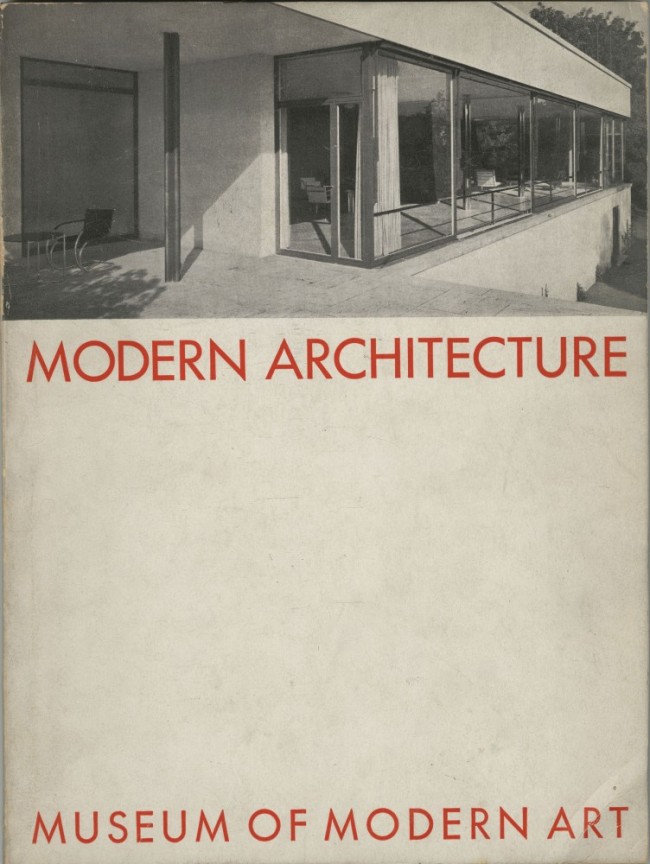

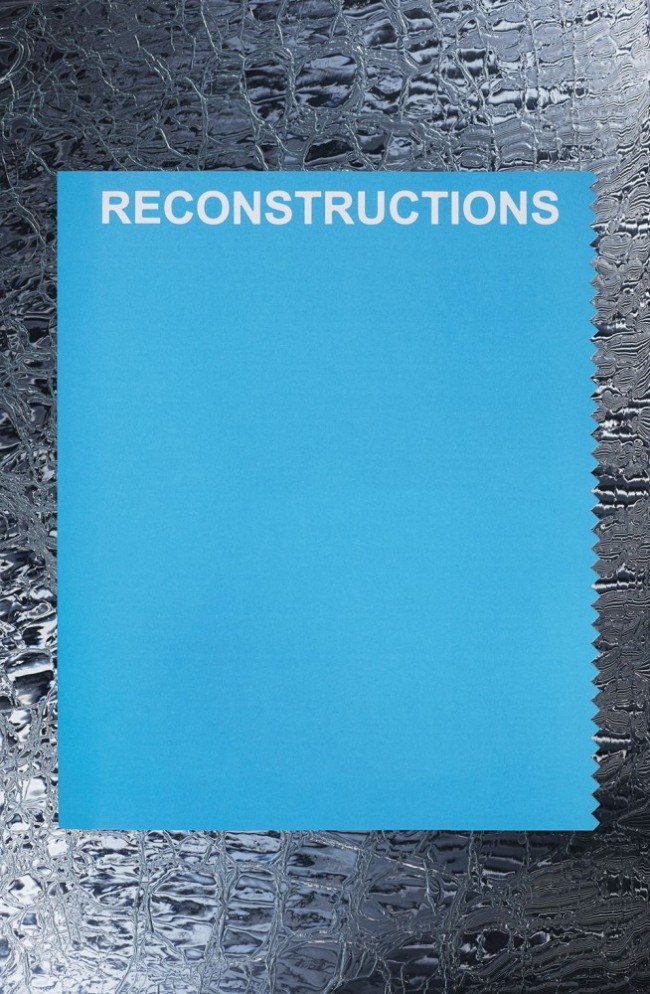

𝘖𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘰𝘤𝘤𝘢𝘴𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘰𝘧 Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America 𝘢𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘔𝘶𝘴𝘦𝘶𝘮 𝘰𝘧 𝘔𝘰𝘥𝘦𝘳𝘯 𝘈𝘳𝘵, 𝘗𝘐𝘕–𝘜𝘗 𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘮𝘪𝘴𝘴𝘪𝘰𝘯𝘦𝘥 𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘴𝘵 𝘋𝘢𝘷𝘪𝘥 𝘏𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘵 𝘵𝘰 𝘤𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘵𝘦 𝘷𝘪𝘥𝘦𝘰 𝘱𝘰𝘳𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘪𝘵𝘴 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘴𝘩𝘰𝘸’𝘴 𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘤𝘪𝘱𝘢𝘵𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘢𝘳𝘤𝘩𝘪𝘵𝘦𝘤𝘵𝘴, 𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘴𝘵𝘴, 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘥𝘦𝘴𝘪𝘨𝘯𝘦𝘳𝘴. 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘵𝘦𝘯 𝘱𝘰𝘳𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘪𝘵𝘴 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘢𝘤𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘱𝘢𝘯𝘪𝘦𝘥 𝘣𝘺 𝘪𝘯𝘵𝘦𝘳𝘷𝘪𝘦𝘸𝘴 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘦𝘢𝘤𝘩 𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘤𝘪𝘱𝘢𝘯𝘵 (𝘴𝘦𝘦 𝘣𝘦𝘭𝘰𝘸). 𝘗𝘐𝘕–𝘜𝘗’𝘴 𝘙𝘦𝘤𝘰𝘯𝘴𝘵𝘳𝘶𝘤𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘚𝘱𝘦𝘤𝘪𝘢𝘭 𝘦𝘥𝘪𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘪𝘴 𝘢𝘭𝘴𝘰 𝘢𝘷𝘢𝘪𝘭𝘢𝘣𝘭𝘦 𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦. 𝘈 𝘗𝘐𝘕–𝘜𝘗 𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘯𝘦𝘳𝘴𝘩𝘪𝘱 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘛𝘩𝘰𝘮 𝘉𝘳𝘰𝘸𝘯𝘦.

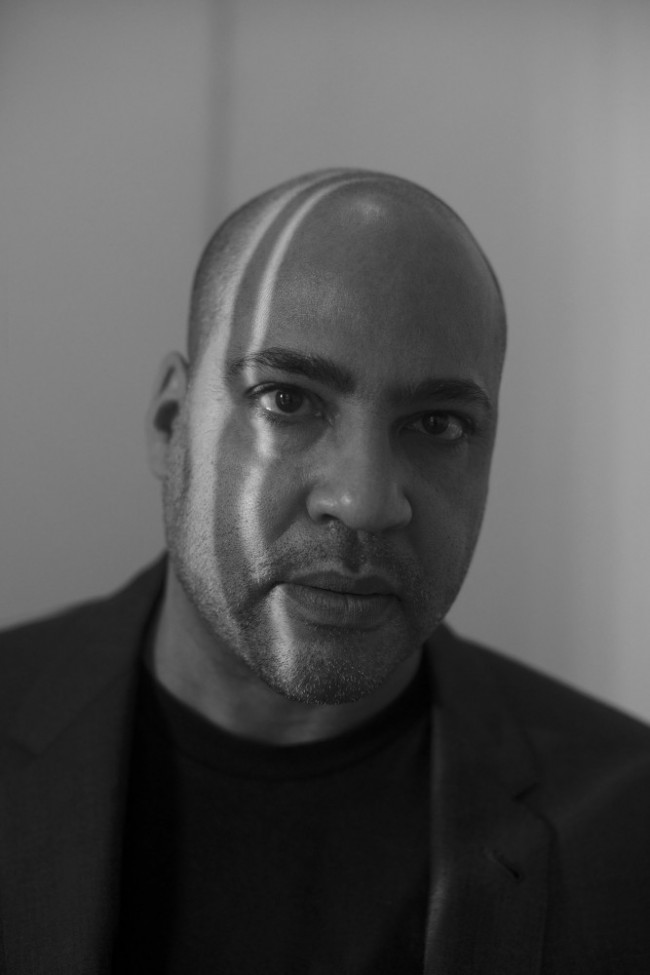

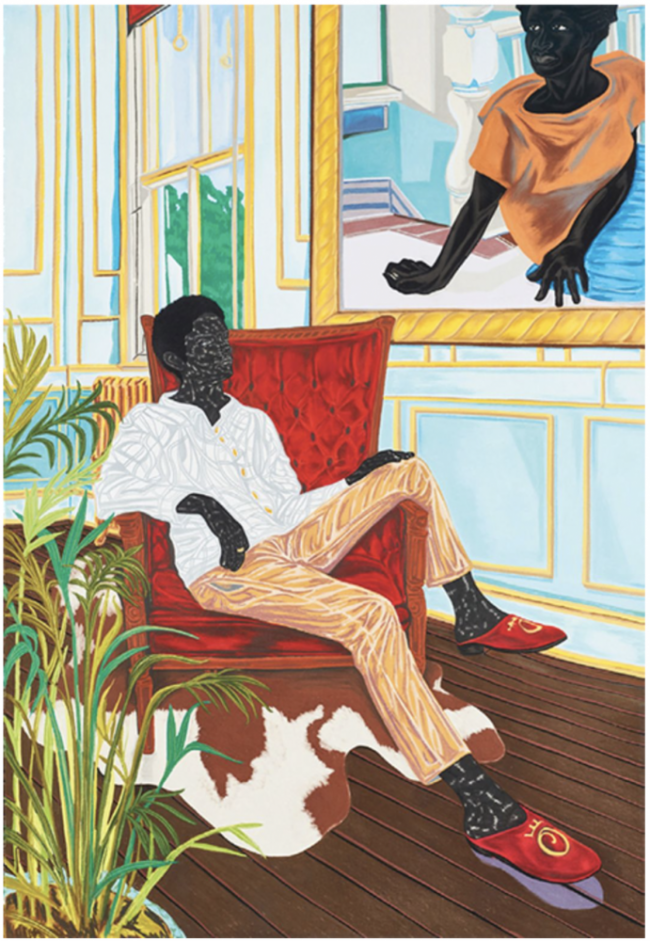

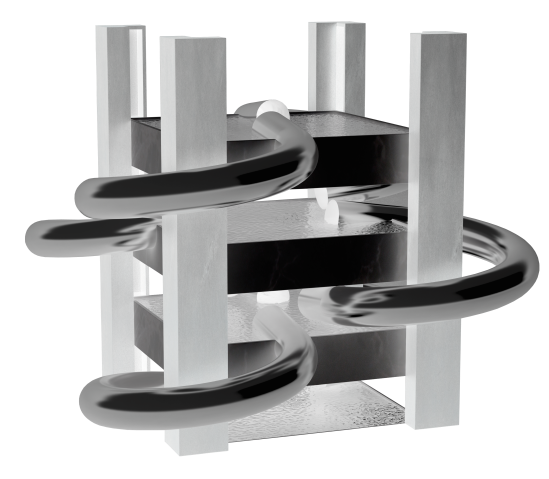

Olalekan Jeyifous is a Brooklyn-based Nigerian-American visual artist and designer. Trained as an architect, Jeyifous often works in public spaces, realizing outdoor sculptures, plastering buildings with banners, and devising murals. He also creates widely exhibited artwork, including mappings and models of the past, present, and even possible futures — a recent project is an Afro-, agro-, and eco-futurist speculative vision for Brooklyn’s Crown Heights neighborhood.

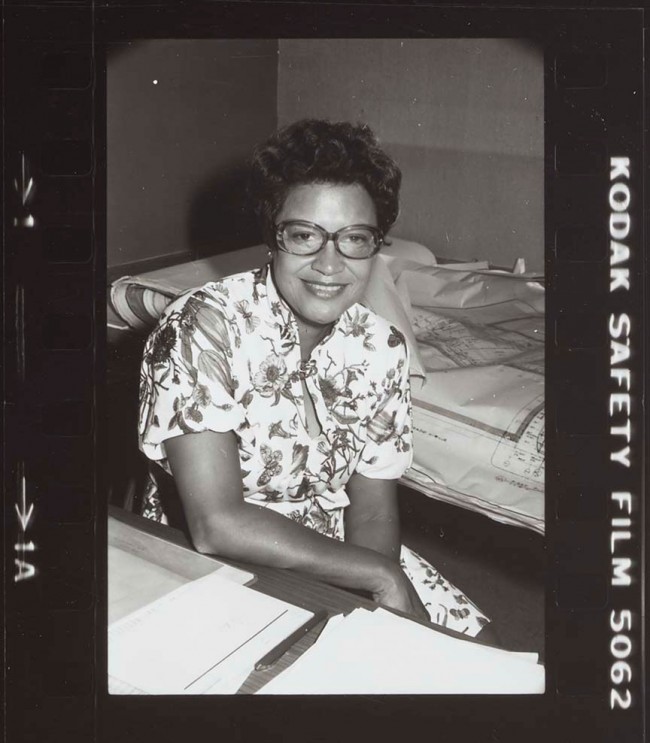

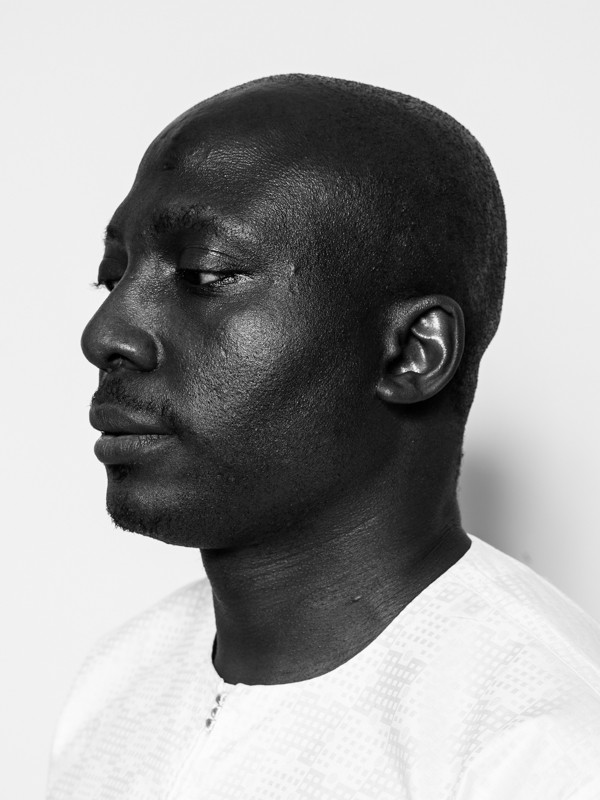

Olalekan Jeyifous photographed by David Hartt for PIN–UP.

PIN–UP: What led you to architecture?

Olalekan Jeyifous: Before architecture was a medium for any sort of sociopolitical, cultural, or environmental inquiry it was Saturday visits to the public library to pore over coffee-table books on anything from Danish furniture design and Japanese architecture to contemporary West African art. My mother would make observations about the various images we were looking at, point things out, and prod me with questions. I was around six or seven at the time, and that’s when I started loudly declaring that I wanted to be an architect. Because it was rooted in a kind of sunny childhood wonder, I had no pretensions about what pursuing this field might entail or where it would lead, and as a result it’s been a constant and revelatory journey of discovery.

How has your practice evolved?

I never pursued the traditional architectural trajectory. I liked the immediacy of being able to articulate my ideas very quickly and saw an opportunity to structure a visual-arts practice around my architectural education and design process. My early work was rooted in the traditional conventions of architectural representation: plans, elevations, sections, and models. But, over time, I was able to expand the parameters of my practice to include whatever media felt appropriate for the narratives I was exploring. I started really looking at producing speculative imagery, experimental animation, and, more recently, large-scale public art, which I feel reconciles my architectural background with my artistic practice in productive and enlightening ways.

What does “reconstructions” mean to you? Both as the title of the show and as a historical or contemporary reference?

As a title, Reconstructions, in an architectural sense, takes on a much grander and perhaps even presumptuous tone as it concerns using design to reform/transform a system that runs quite effectively as it was intended. As an ever-evolving point of reference, I consider reconstruction to be everything Black people in this country have done to navigate, survive, and thrive within a nation designed at every turn to obstruct that process, a process which often confronts notions of space, access, and belonging.

Can you describe the project you are creating in response to the MoMA Reconstructions brief? Where is it and why did you choose that location?

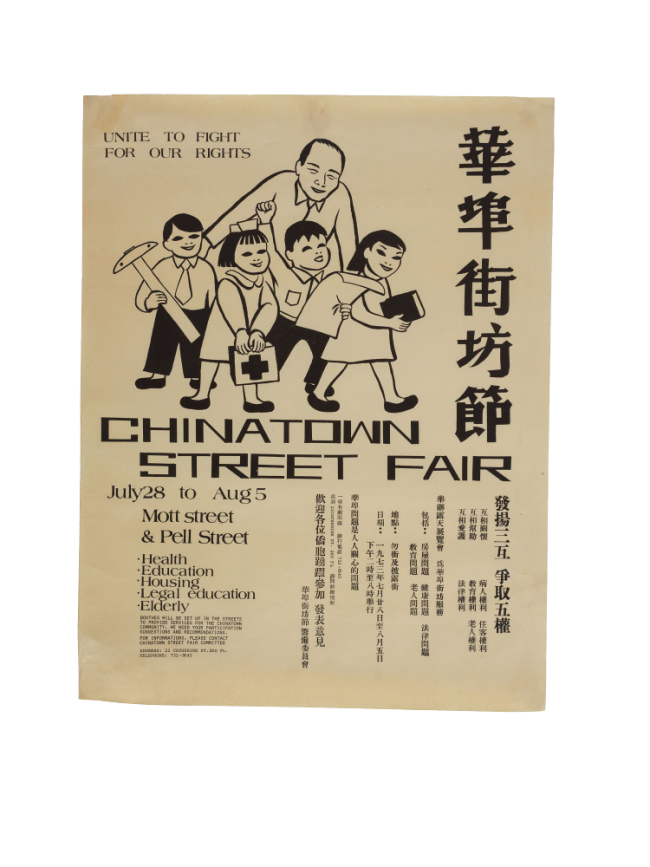

My project is located in New York City and more specifically Brooklyn, where I have resided for 20 years. It imagines an alternative retro-future in which the world discovers the dangerous effects of fossil fuels in the late 70s. As a result, the U.S. federal government establishes a system of “mobility credits” wherein each person is afforded a finite amount of movement at the city, state, and national levels. In support of the free market, the law also provides that the credits would be transferable and salable, and so a system of personal-mobility allowance that was created to reduce pollution is quickly corrupted by the American principles of capitalism resulting in new inequalities mapped along racial and ethnic lines. This system is then examined through Brooklyn and New York City where it is most acute, and where a social geography quickly emerges in which certain communities have sold away almost all their rights to leave their immediate environs. I imagine what these communities look like and how they survive and adapt through a series of “architectural” improvisations. As always my work takes an inverse approach to the prevailing public perception of architecture as a problem-solving endeavor.

Interview by Drew Zeiba

Video portrait by David Hartt

Editing by Jessica Lin

Music by King Britt presents Moksha Black

A PIN–UP production in partnership with Thom Browne

This video is part of a series of ten portraits David Hartt created for PIN–UP on the occasion of Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America at the Museum of Art (Feb 20–May 31, 2021), curated by Mabel O. Wilson and Sean Anderson. The portraits were also published in the print edition of PIN–UP 29.