INTERVIEW: The Late Nanda Vigo, Radical Artist And Designer Light-Years Ahead Of Her Time

Italian artist, designer, and architect Nanda Vigo rose to prominence in the 1960s with an interdisciplinary practice defined by idiosyncratic reimaginations of light, materiality, and space. After setting up her own atelier in Milan in 1959, she played a pivotal role in the avant-garde art movement Zero, and collaborated with figures such as Lucio Fontana, Gio Ponti, Enrico Castellani, and her late partner Piero Manzoni. Her projects, which included the all-white Zero House (1959–62), the tile- and fur-filled Lo Scarabeo sotto la Foglia house (1965–68, with Ponti), and her many glass-and-aluminum Cronotopi light pieces, all transcend the categories of art, design, and architecture. Vigo remained active until her death at 83, her work possessed by an ineffable originality shaped by limitless curiosity. At the time of her passing in May 2020, she was working with Serpentine curator Hans Ulrich Obrist on what would turn out to be a posthumous project — a space for children designed for the Enzo Mari exhibition, which is being shown at Milan’s Triennale this fall. Two years earlier, in January 2018, Obrist recorded an interview with Vigo in her Milan studio. Their conversation, published here for the first time, finds her looking back on her decades-long career and on a legacy that, despite Vigo’s enormous influence on radical Italian design, still remains underestimated.

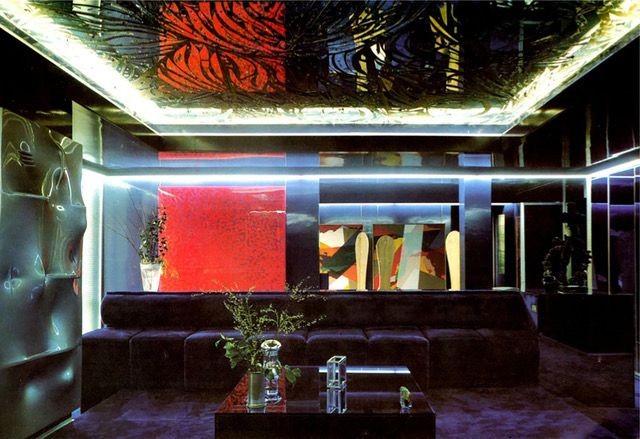

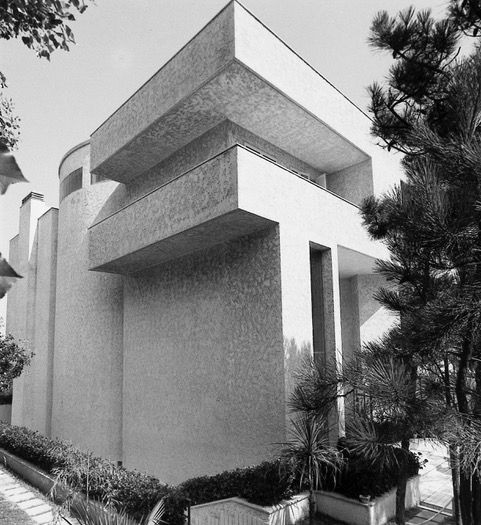

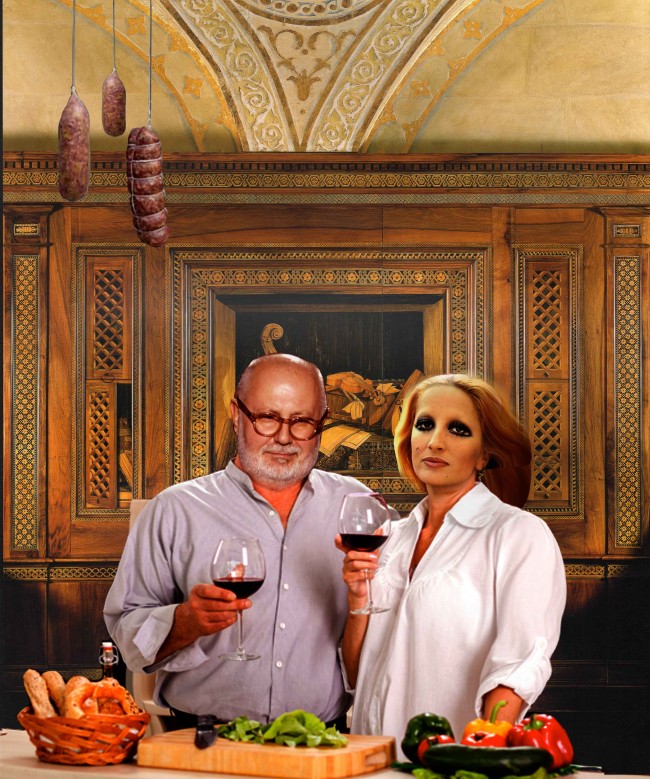

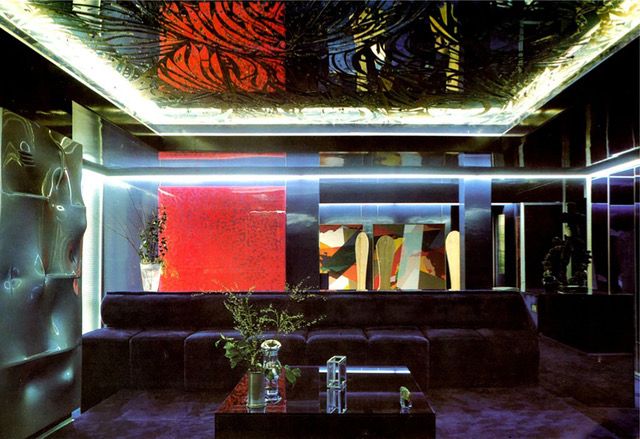

Nanda Vigo, private residence in Verona, Italy (1988–89).

Hans Ulrich Obrist: How did you start out in art and architecture? Was there an epiphany?

Nanda Vigo: When I was a girl, my family evacuated from Milan to Como during World War II. Walking through Como with my parents one day, we came across Giuseppe Terragni’s Casa del Fascio. I was fascinated by Terragni’s use of glass bricks. They fractionalize the artificial and natural light to such an extent that the architectural volumes are transformed. I wanted to become an architect. I am convinced I was an architect in a former life. But I found architecture alone to be insufficient. I went to a fine-arts academy, because in my mind one type of study furthered the other. Then I went to the Lausanne Polytechnic in Switzerland, a fun and advanced school that had students work with their hands directly, laying bricks with mortar. I didn’t study at the Milan Polytechnic, because my plan was to go to America, and the Milan school wouldn’t give me credits that were valid in the U.S., while the Swiss school did. I was interested in American culture, especially music and literature — a bit less in the artistic scene.

You specifically went to meet Frank Lloyd Wright and see his Fallingwater House in Pennsylvania, right?

All of us artists and architects were fascinated by Fallingwater. But once I got to Taliesin West (Wright’s Arizona base where he ran his educational fellowship), I saw how Wright hadn’t really done anything special at all. The idea to build on the waterfall was the client’s, not his. All Wright’s furniture looked like leftovers from the Vienna Secession, but painted white. After this disappointment, and seeing Wright’s nasty temper, I fled Taliesin. He used to smack students with a ruler if they made mistakes. He was always angry. I told myself I’d never learn anything there, so I went to San Francisco and interned in a few offices.

Nanda Vigo, Due Piu chair (1971); produced for the More coffee shop, Milan. Photography by Aldo Ballo.

You were in San Francisco in 1958 and 1959. In his book **1959: The Year Everything Changed (2009), Fred Kaplan says that, contrary to what we think, the revolutionary years were not only the 1960s but also the 1950s, with the Beat generation and political, sexual, and artistic liberation. Like Ettore Sottsass, your interests were multidisciplinary, and included literature. Tell us about the climate in San Francisco in 1959.

**All of us adored John Dos Passos, Ernest Hemingway, the poets of the Beat generation, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Jack Kerouac. Jazz music was everywhere. The atmosphere was fantastic.

Is there a catalogue raisonné of your work? What do you consider the first project of your career?

I don’t have a catalogue raisonné, but I’m working on a chronology of my work with Tommaso Trini, to be published by Edizioni Prearo. As for my first project, I think I went to the U.S. too soon, because the concept of art did not yet exist in architecture. Art was something architects hung on the wall as a decoration. Design offices had such an assembly line of work that no one could interrupt the flow to make models and trial pieces. So I had to get back to Italy, where I knew different specialized artisans with whom it was possible to try things out. As soon as I got back, I received a job for an apartment interior. Luckily, this was a young husband-and-wife couple called Pellegrini who gave me carte blanche. This was my first white interior, which I later called Casa Zero. I stripped the entire house. Those were the days when everyone wanted wooden Swedish-style furniture.

Nanda Vigo, Casa Museo Remo Brindisi in Lido di Spina, Italy (1967–71). Photography by Gabriele Tocchio.

The name reflects your interest in the Zero group of artists. How did your contact with Zero begin?

When I started out, I worked at Fontana’s atelier for a few years doing small jobs, an advantageous situation for me, because he was the only artist who interested me at the time. In his manifesto of Spatialism, he declared the possibilities of transmitting light into space in such terms that I identified with his thinking. He was the one who told me about Zero, these young people in Germany. It was an absolutely important movement, many artists took part, with very diverse types of expression. The possibility of exhibiting as an experimental group was highly attractive. Plus, the young artists from Düsseldorf, Otto Piene and the others, were working with light and different materials, so there was a common feeling.

Then the artist Piero Manzoni, who you were engaged to, forbade you all contact with Zero. Was he jealous?

Terribly so! Unfortunately, I was absolutely in love with Manzoni, so I accepted it all. Of course we fought a lot, and the quarrels were only for one reason. He’d say, “This is not the Curie family. I am the artist and you stay home.” No one can believe it. I was already wearing miniskirts, and he made me let the hems out. I was not allowed to speak. Fontana had warned me — he was extremely generous, not only in helping young artists and buying their paintings, but also in offering his knowledge, which was greatly to my advantage.

Nanda Vigo, living room interior of the Zero House (1959–62). Photography by Casali Domus.

So you designed the Zero House in 1959 and you integrated it with artwork?

Yes, pieces by Enrico Castellani and Fontana.

The Zero House is rather minimalist.

Yes. Like I said, back then everyone wanted wooden furniture from Sweden, which I abhorred. Also, there was the “furniture effect,” meaning a buffet had to look like a buffet, and a cabinet had to be a cupboard. What I did was integrate the furniture inside the walls of the house. There was also a play of light.

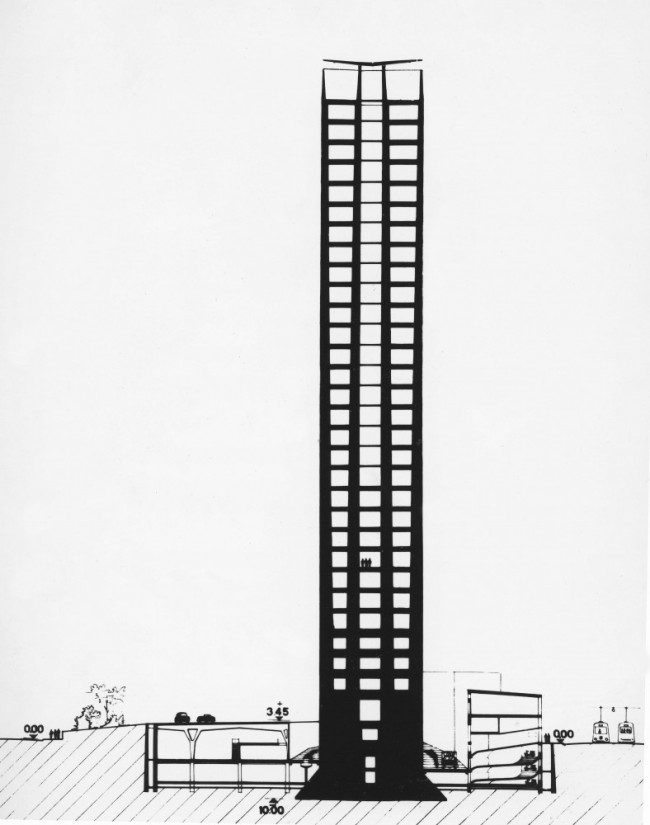

In the same year, 1959 when everything was happening, you designed a sort of skyscraper in Rozzano, the Milanese suburb where **Domus is located.

**I was working for a small studio — two engineers and an architect. The town of Rozzano asked for a municipal cemetery. My initial idea was related to the problem of rising land prices. So I drew twin towers with burial recesses on vertically stacked levels. The press dubbed it the “cemetower.” Only the lower parts were built.

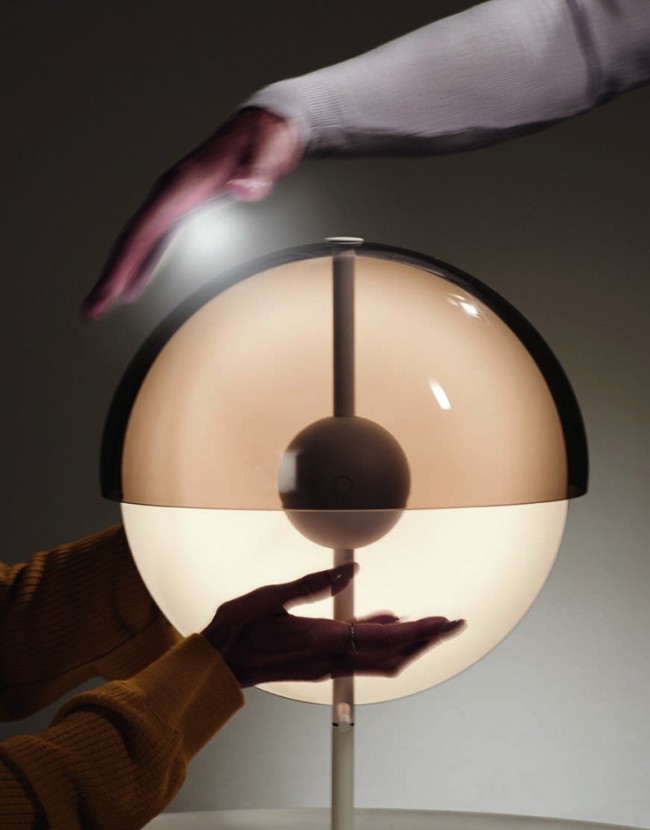

Nanda Vigo, H&S Table (2019); produced for the exhibition Hard & Soft at Luca Preti gallery, Milan.

More Mies van der Rohe than Frank Lloyd Wright, don’t you think?

Yes indeed, my mistake — I should have gone to Mies!

So Mies was inspiring?

Certainly. He was on the same line as Terragni.

How did you become interested in African and Eastern cultures?

Africa was part of my explorations, all of which were entirely personal. I was interested in human races, their migration across the planet and how groups formed that led to the origins of culture, writing, and languages. I was interested in the vibrations of different peoples. The history of Egypt was at the top of my list, so I went there many times to look around and try to understand the culture. This brought me to seek out all the circumstances under which pyramids were built, so I went to Mexico and India, studied religions and the different branches of Hinduism. I spent much time with Tibetan lamas.

Much like Alighiero Boetti.

Much earlier than Boetti.

What year was this?

Before 1970.

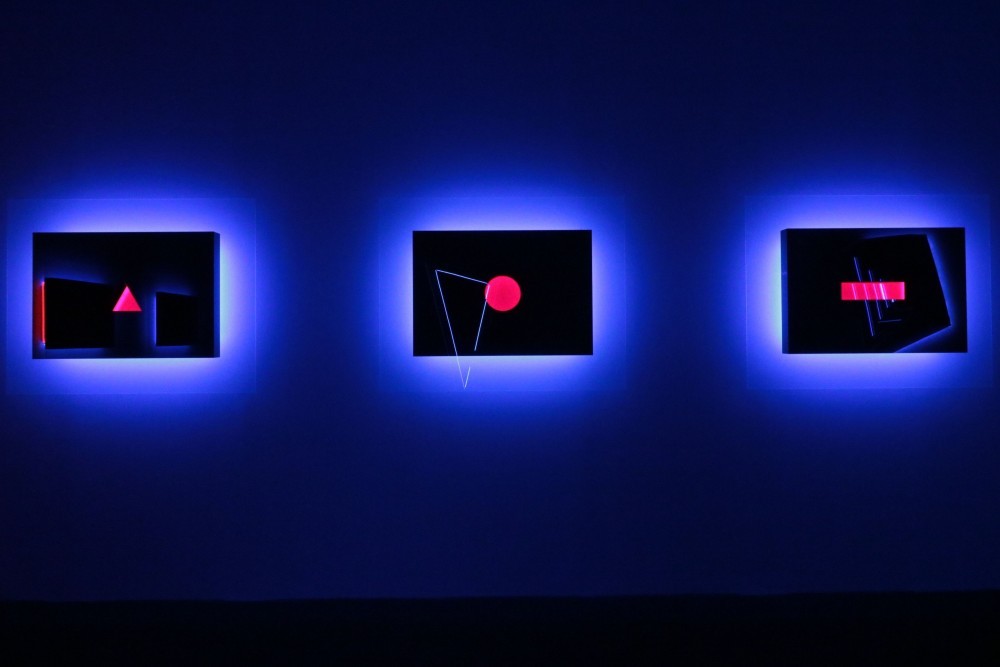

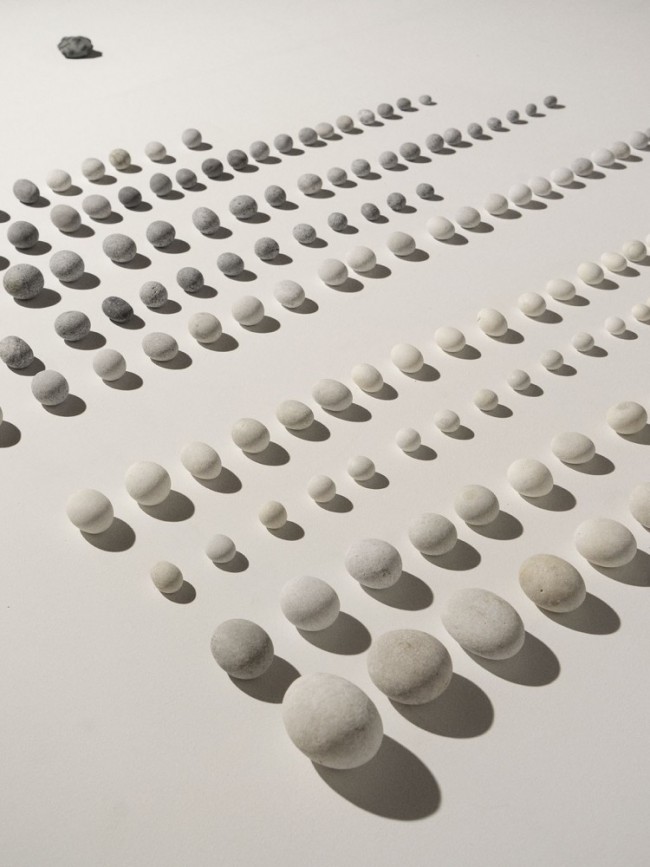

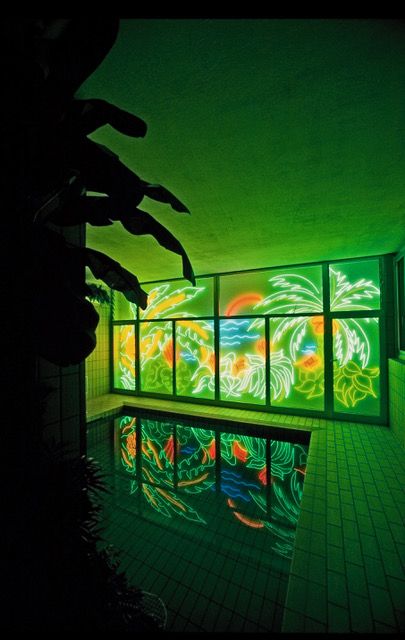

Exhibition view of Nanda Vigo — Light Project (2019) at the Palazzo Reale, Milan. Photography by Marco Poma.

Did you take photos on these trips?

Yes, but not many.

Not systematically like Sottsass?

No, exactly the opposite. If you’re there to take photographs, that’s all you end up doing. Instead, I wished to understand the culture, insert myself into the local system, and so I did.

Did you translate your travels into writing or work?

No. I knew I could never transmit them, because no one was interested. Only recently have critics become curious about the backstage perusals of artists, but it used to be that you couldn’t even talk about them.

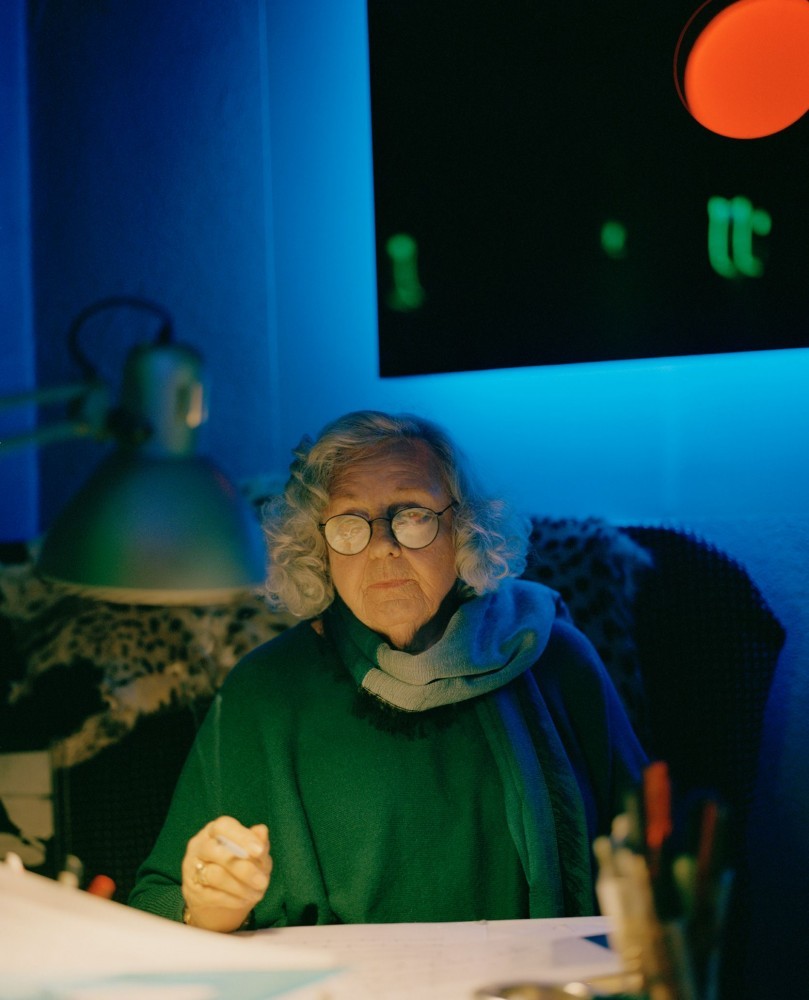

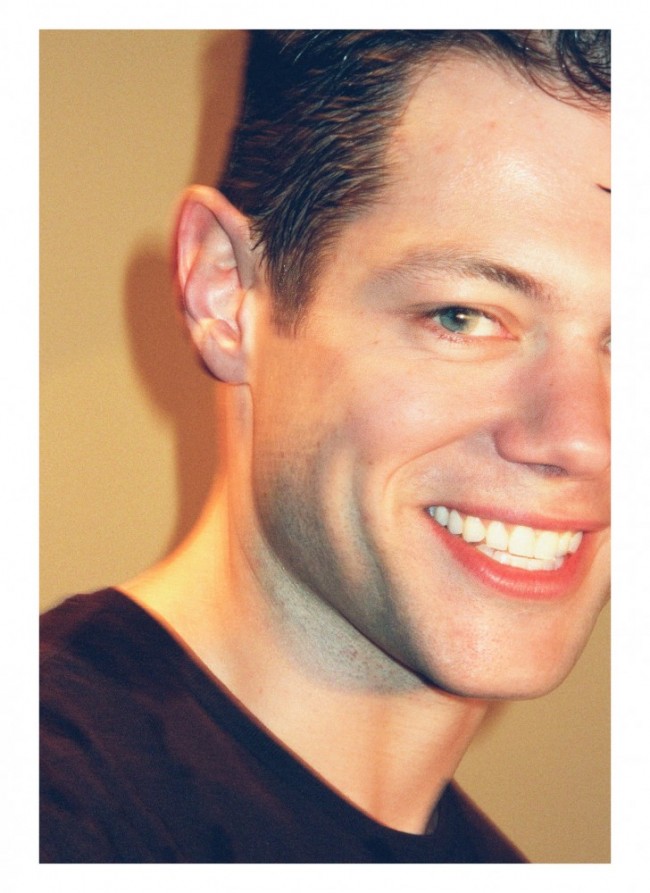

Portrait of Nanda Vigo by Bea De Giacomo photographed in 2017 in the artist’s studio in Milan. Courtesy Bea De Giacomo.

Aren’t there any traces of these travels? Did you make work inspired by the experiences?

I made many tapestries in Kashmir. They can be used as rugs, too, thanks to the needle technique. I stayed there to follow the production, because if you just leave the drawings there, they invent everything themselves. Some are abstract, others are figurative. Some were for Flou, the bed manufacturer. They wanted tapestry panels for behind the beds.

Is any of your other work inspired by these trips?

No, but I did continue designing rugs, because my Tibetan friends succeeded in founding a rug company in the Nepalese capital Kathmandu. These were knotted by Tibetans who had escaped from China. I made beautiful rugs with them.

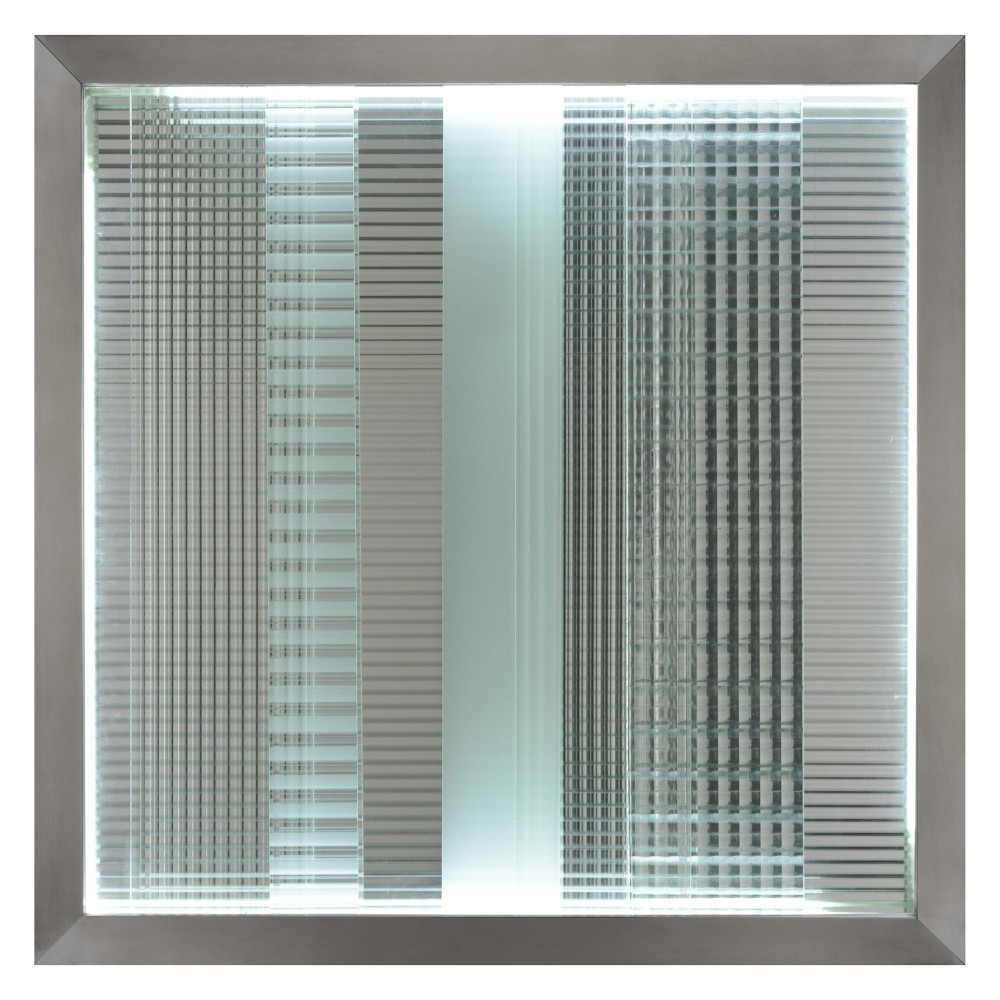

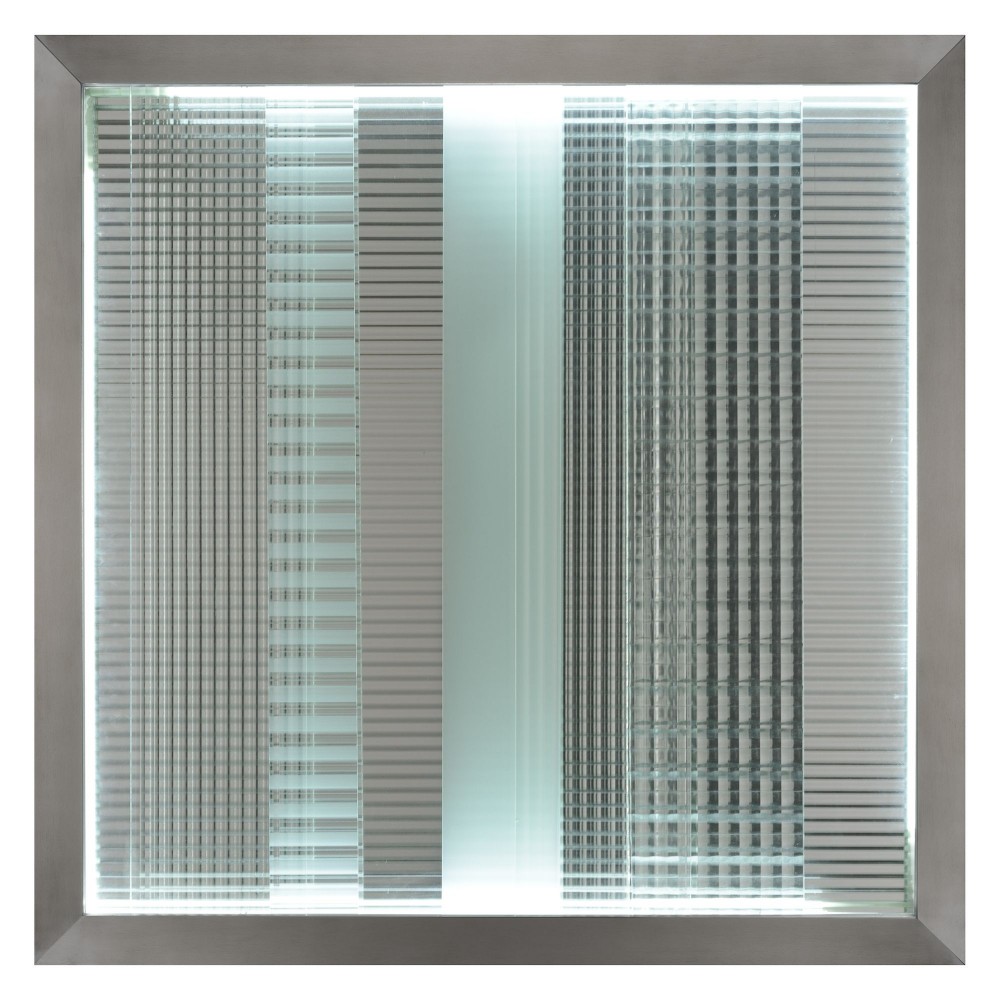

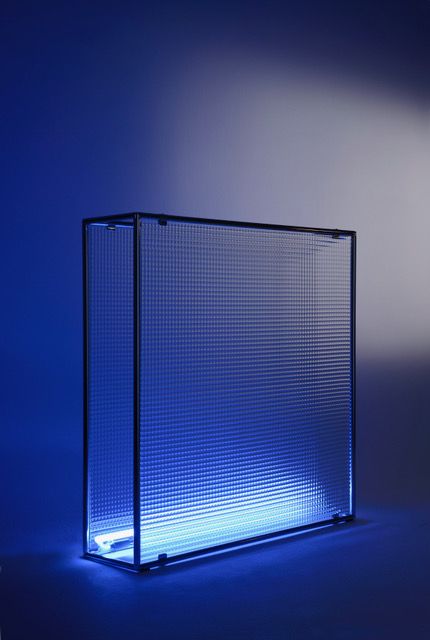

Nanda Vigo, Cronotopo (1969): aluminum frame, printed glass, and neon, 80 x 80 cm. Photography by Emilio Tremolada.

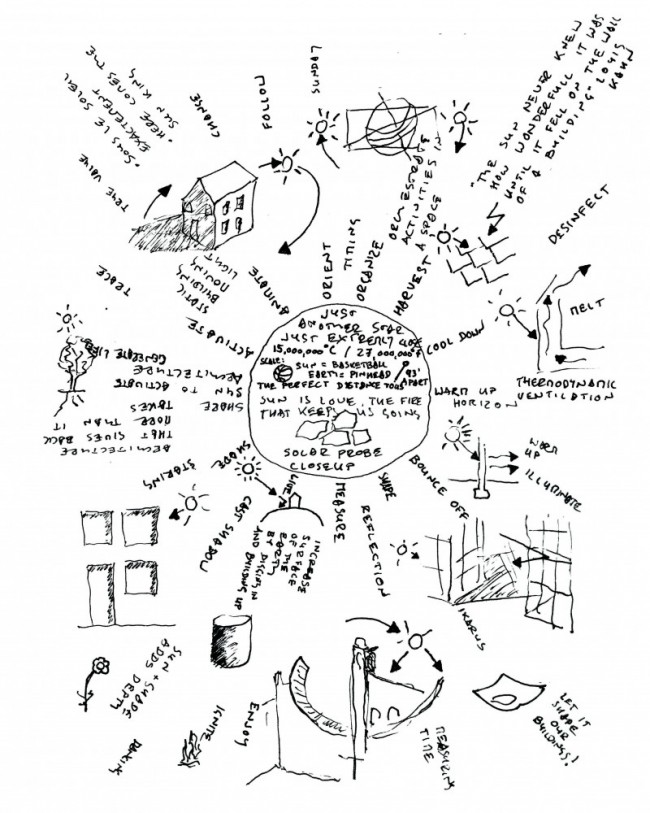

The interesting thing about you is the freedom and fluidity with which you move between art, architecture, and design. It’s an interesting theme for the new generation of artists. You are not imprisoned in architecture. How did you do it? How did the time-space idea for your **Cronotopi originate?

*It started with the light I saw flowing through Terragni’s glass bricks. It never left me. I thought a transmission of things for the future could come about through the use of light, so I attempted to develop this when I designed Casa Zero, and continued after that. I called these elements Cronotopi, from cronos-topos*, time-space. What I wish to obtain by refracting light is that the viewer is induced, almost forced, to think of the light. It’s such an important element in our lives.

I saw your beautiful show at Sperone Westwater Gallery in New York (October 2015–January 2016). There were Cronotopi there. And there was a second group of objects from the 1970s, called Triggers of the Space — mirror sculptures with triangular and pyramidal shapes. What does the name mean?

I used the verb trigger in my 1964 manifesto to mean what I just mentioned, namely to activate the spectator by means of light. The object creates a luminous space that makes people think about light.

In 1969, Sottsass wrote in Domus about your “interplanetary” quality. This aspect is interesting to young artists. What about your intergalactic dimension? Have you designed things for other planets? For Mars?

No. I am working on an Alcantara-sponsored exhibition about Paolo Soleri at the Maxxi in Rome, titled Arch/arcology (shown in February 2018), which is a play on the words Arcosanti and architectural archaeology. If you look at his spatial projects, they indicate that cities have become archaeology. I have had this thought since I was a girl, when I used to read Flash Gordon comic books in the 1940s.

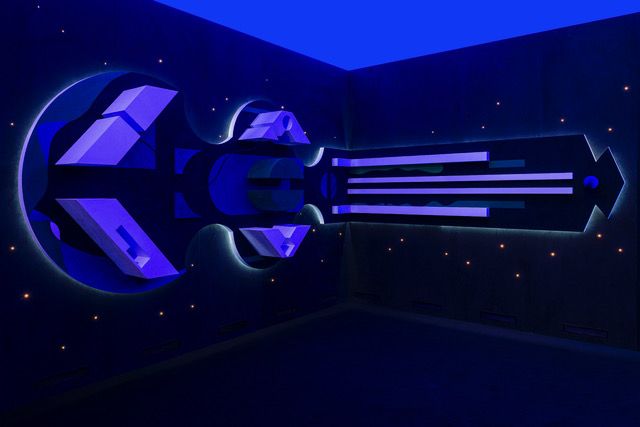

Nanda Vigo, Arch/arcology (2018) at the MAXXI Museum, Rome. Photography by Sebastiano Luciano. Courtesy Alcantara and Foundation MAXXI.

Was Flash Gordon the inspiration for your intergalactic work?

No. The comic strips were always about a planet where all the buildings were suspended in an anti-gravitational void. The idea stayed with me, the desire to go beyond. I organized another exhibition for Alcantara at the Palazzo Reale in Milan (Fantasy Access Code, 2017) and succeeded in constructing a model of my favorite spaceship, the Enterprise from Star Trek. I’ve always been interested in science fiction, starting with the old Japanese films. In the late 1950s, they were the only ones making science-fiction movies.

What about your collaboration with Gio Ponti on the house Lo Scarabeo sotto la Foglia (The Beetle Under the Leaf, Malo, 1965–68).

Ponti published the design of the house in Domus, offering the project free to anyone who wanted to build it. Only one person came forward, someone I knew because he had begun collecting art (Giobatta Meneguzzo). He lived outside Vicenza in the town of Malo. He knew I was a friend of Ponti’s, so he asked me to help out. The design was for a small vacation house, furnished with tiny bunk beds. There was no way to use the interior, but this gentleman wanted to live there with his wife and two children. There was very little space, so the interior needed to be redesigned. He asked Ponti if it was okay that I made the interior. I was so happy, I arrived one day at Ponti’s office with a stack of drawings. I wasn't sure whether to make it in his style or start from scratch. Ponti put his hand on my drawings and said, “I don’t want to see anything. Show me when you’re finished.” So the house is by Ponti and the interior is mine.

-

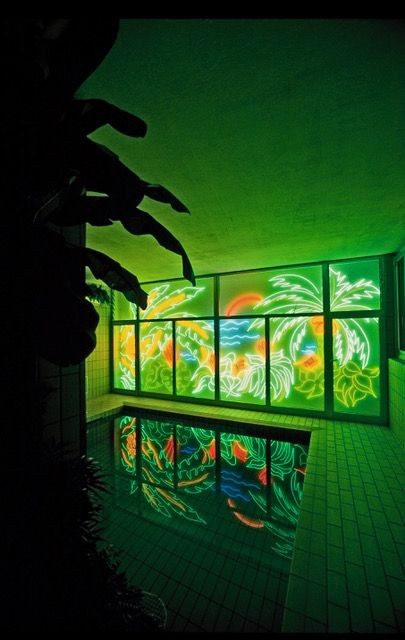

Nanda Vigo, Lo scarabeo sotto la foglia (1965-68). Photography by Casali Domus.

-

Nanda Vigo, Lo scarabeo sotto la foglia (1965-68). Photography by Casali Domus.

Would you say Ponti was an inspiration in your approach to design?

No, Ponti did not inspire me. My thinking was similar though. People called me crazy, so I needed someone who thought like I did — that person was Gio Ponti. Once we began talking and discussing things, I said to myself, “If Ponti is here, I am not alone,” so I forged ahead.

Who were your influences in art?

No one influenced me in anything. Not at all. All my things are mine alone. Naturally, I liked Enrico Castellani's work, Günther Uecker and Heinz Mack, but no one influenced me. I worked at length with Lucio Fontana and, luckily, he did not influence me.

Tell us about the **Utopie display for the Triennale di Milano in 1964.

**When Fontana was asked to design a setting, he wrote a few lines of description and made a couple of sketches. Then he needed to develop them. I often did that for him. When the request came for these installations, he said, "You go. You do it." One I made for him, and the other we made together.

Nanda Vigo, living room of Casa Blu, Milan (1967–72). Photography by Marco Caselli.

What was your view of the historical avant-gardes of the 20th century? Russian Constructivism, say — El Lissitzky, Alexander Rodchenko?

Naturally the Russian constructivists were a love all we all had, inevitably. Likewise, we had a great love of the German artists working in Berlin.

Do you have any unbuilt projects? Dreams?

I am never able to build everything I have in mind, because it would cost too much. I would like to go larger in scale, like the project I made for the University of Milan.

Would you like to build a city?

No. My job is giving indications about what will come, what to think about the future. I am uninterested in materially building a city.

Nanda Vigo, Diaframma (1968): Aluminium, glass, neon, tubes.

Have you ever published your writings?

No. When I write, I write the truth, for instance what happened with Piero Manzoni. But then I was asked to rewrite what I had said about how he died, how many pieces he had made — the Manzoni Foundation prevented me from telling the truth.

How did Piero Manzoni die?

He drank himself to death. His liver went kaput. But the foundation people invented a heart attack, which is not true. They didn’t want to say he was a drinker. Then there was more trouble for me when I stated the amount of work he had made. They made a catalogue of 800 pieces, but where they came from no one knows. He worked for just three years. He did not assiduously paint and make objects. He was mostly out with his artist friends for a glass of wine and good conversation. He was not someone to spend day and night toiling in his studio.

What would be your advice to a young artist or architect?

For someone working in art and architecture, I’d say, “Study all you can! Study what happened in the past.” If you don’t check item by item what happened before, what the evolutions were, you cannot go forward. Everyone is at an absurd standstill now.

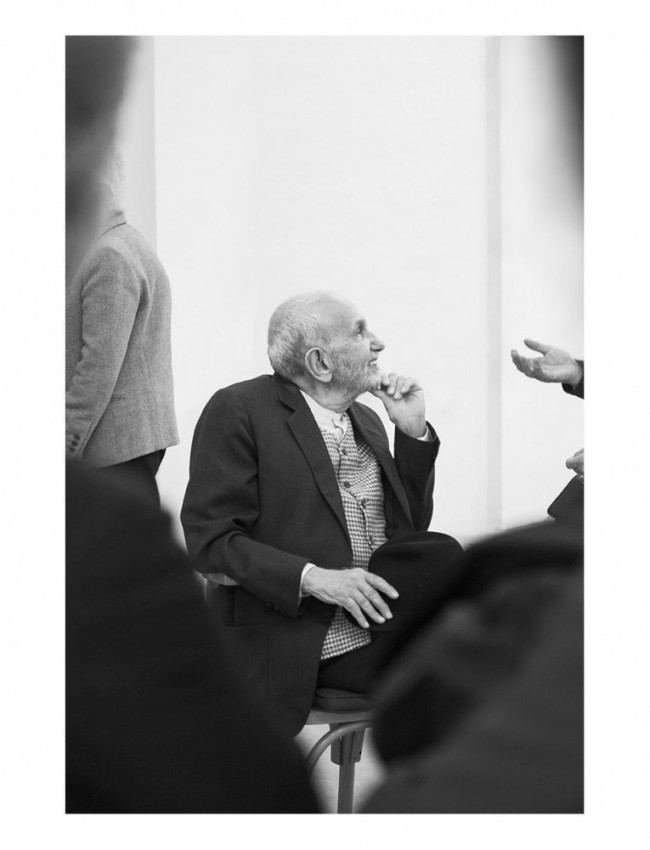

Interview by Hans Ulrich Obrist.

All images courtesy Nanda Vigo Archive, Milan, unless otherwise noted.

Special thank you to Alberto Podio.

Nanda Vigo’s interpretation of Enz Mari’s toy object can currently be admired at the Triennale in Milan, Italy, as part of the exhibition Enzo Mari Curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist.