RECONSTRUCTIONS PORTRAIT: Felecia Davis on Reconstructing Technology

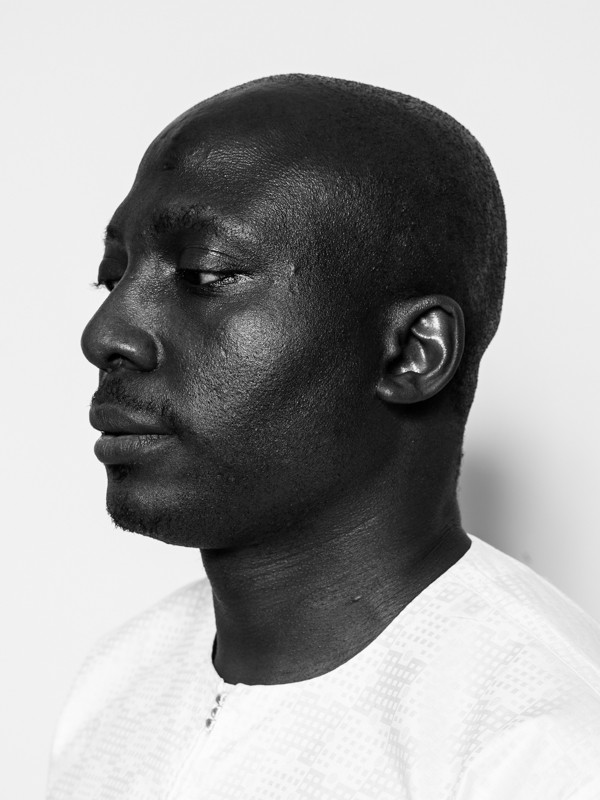

𝘖𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘰𝘤𝘤𝘢𝘴𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘰𝘧 Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America 𝘢𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘔𝘶𝘴𝘦𝘶𝘮 𝘰𝘧 𝘔𝘰𝘥𝘦𝘳𝘯 𝘈𝘳𝘵, 𝘗𝘐𝘕–𝘜𝘗 𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘮𝘪𝘴𝘴𝘪𝘰𝘯𝘦𝘥 𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘴𝘵 𝘋𝘢𝘷𝘪𝘥 𝘏𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘵 𝘵𝘰 𝘤𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘵𝘦 𝘷𝘪𝘥𝘦𝘰 𝘱𝘰𝘳𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘪𝘵𝘴 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘴𝘩𝘰𝘸’𝘴 𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘤𝘪𝘱𝘢𝘵𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘢𝘳𝘤𝘩𝘪𝘵𝘦𝘤𝘵𝘴, 𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘴𝘵𝘴, 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘥𝘦𝘴𝘪𝘨𝘯𝘦𝘳𝘴. 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘵𝘦𝘯 𝘱𝘰𝘳𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘪𝘵𝘴 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘢𝘤𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘱𝘢𝘯𝘪𝘦𝘥 𝘣𝘺 𝘪𝘯𝘵𝘦𝘳𝘷𝘪𝘦𝘸𝘴 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘦𝘢𝘤𝘩 𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘤𝘪𝘱𝘢𝘯𝘵 (𝘴𝘦𝘦 𝘣𝘦𝘭𝘰𝘸). 𝘗𝘐𝘕–𝘜𝘗’𝘴 𝘙𝘦𝘤𝘰𝘯𝘴𝘵𝘳𝘶𝘤𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘚𝘱𝘦𝘤𝘪𝘢𝘭 𝘦𝘥𝘪𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘪𝘴 𝘢𝘭𝘴𝘰 𝘢𝘷𝘢𝘪𝘭𝘢𝘣𝘭𝘦 𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦. 𝘈 𝘗𝘐𝘕–𝘜𝘗 𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘯𝘦𝘳𝘴𝘩𝘪𝘱 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘛𝘩𝘰𝘮 𝘉𝘳𝘰𝘸𝘯𝘦.

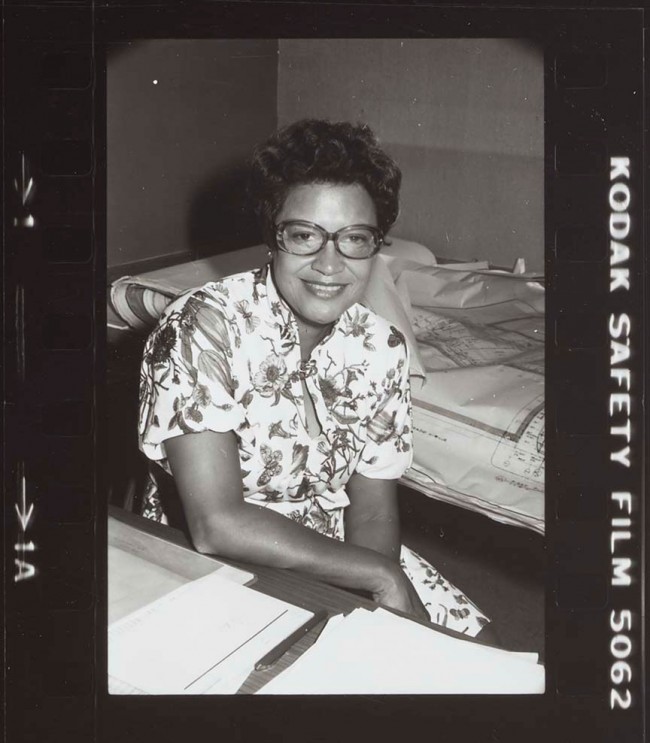

Engineer, architect, and researcher Felecia Davis explores the soft side of hardware. Synthesizing computational practice, digital fabrication, and textile design, Davis creates responsive wearables, objects, and environments from fabric. Recent projects include hospital curtains that respond to touch and textile walls that morph in response to sensor data corresponding with occupants’ emotions. In addition to running FELECIADAVISTUDIO, Davis is Associate Professor at Penn State College of Arts and Architecture as well as director of the college’s computational-textiles research group SOFTLAB.

Felecia Davis photographed by David Hartt for PIN–UP.

How did you come to your current approach to design and your understanding of technology?

Making textiles — like learning to knit, weave, or sew — was something I was drawn into as a kid with my mother, sister, and aunts. As I understood more about what I thought design computing was, the more I saw how much of what I had learned textile making was part of a computational culture and was in fact computational design. This included the segmentation, counting, addition, or subtraction of stitches, colors, and shapes to make patterns, recombining shapes, substitution, repetition, and all the tasks your brain does when making a textile design or for that matter making anything at any scale. Textile design was one of the first design fields to be technologically transformed from hand craft to machine production because of this specific culture of seeing the world — the over and under positions for weaving become an on-or-off system of logic that connects directly with the 0s and 1s of computers. This is just a small part of textile culture that was developed for new technologies. There are many other aspects from textile culture that are available for us to think about development in computation, such as touch, for example, or emotion. Understanding the contributions of computational cultures outside of scientific cultures of computing will present other ways of problem framing and problem solving for designers and for people who make things.

What does this look like in your practice today?

I look at how technology embedded in textiles, such as sensors, microcontrollers, or transformed natural properties of fibers can communicate information to people. The things that get made in my practice have a wide range of scales, from very small and wearable to the size of a wall or building. I look at the implications these textile technologies have for architecture and design in general at all scales. These technologies have changed some core issues for design and architecture, such as what is meant by threshold, inside, or opacity, for example. Understanding more about computational design and computational textiles has caused me to examine the intersection between real materials such as fibers and the information that goes into or is programmed in the construction of a computational material. That duality is of great interest. Often when people talk about computation, particularly in architectural design, they mean graphic work on computers — or in fact anything having to do with computers, which is one way to think about computation. I believe there are many ways to think about and work with computation in architecture and design which do not include computers but rely heavily on computing. I like to think about computation as a larger project of understanding the world that we shape and design, which is also a world that shapes us. There are many computing cultures: some do not call themselves that, but they are part of computing culture if one chooses to see it.

What does “reconstructions” mean to you? Both as the title of the show and as a historical or contemporary reference?

I believe our curators are seeking to challenge the sociopolitical structures in place that have resulted in the exclusion of so many Black artists and architects from the galleries and collections at MoMA. Their call to us is a reconstruction of curatorial practices at MoMA. The call of our curators is rebuilding the museum. In my work in design computing, I think that computing culture needs to look outward from its scientific base to other places and other people and understand the multitude of ways of thinking about computation and computational cultures. Reconstruction means an opportunity to pause and think about technologies that knit us together. There is a double-edged blade to the technologies that engage us: on the one hand they can bring us together, help fight for issues that matter, make work efficient, entertain us, and a hundred other things; on the other, social media that have allowed us to connect, in spite of quarantining through COVID–19, can also be used to police, to divide, and to segregate. Many of these technologies emerged from defense-development programs. Additionally, there are serious questions about privacy, for example, that, globally and in the United States, we must begin to answer and create policies for. When one looks at these technologies in the Black community, there are some critical issues that are also born from historical formations. Algorithms made to help us with daily tasks or other things often do not work on Black faces. On the other hand, maybe Blacks are hyper-visible in a system of monitoring cameras placed around an increasingly smart city. Do we need to be able to disappear from a smart city? Can we? There is still a problem with access to technology in many Black neighborhoods, a kind of technological redlining repeated in the cyber world. These problems are, in spite of the newness of technology, historical, writ again through technology. As a country and globally we have to rebuild how we treat people, how we treat the Earth, and how we treat creatures that share the Earth with us.

Can you describe the project you are creating in response to the MoMA Reconstructions brief? Where is it and why did you choose that location?

My project is about the Hill District in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where the playwright August Wilson lived and wrote his ten plays about. My project for Reconstructions is about co-construction and mutual aid. In it I use technology as a connector and communicator through textile networks. Another aspect of the MoMA exhibition is the Black Reconstruction Collective (BRC), which is about Black mutual aid. It was formed by the ten artists and architects who were brought together by the curators and MoMA’s Reconstruction advisory committee. As we were all brought together by these amazing individuals, the BRC welcomes those who have guided and supported us and looks forward to having new members join. The purpose of the BRC is to provide support for design about the African diaspora. It is often tough to explain to a grants jury or judging panel that a project about Blacks is important, so we thought we would form an organization that would focus specifically on that. This is often a stumbling block for many Black artists, architects, and scholars of Black design work who are often not a part of networks of people with access to money and commissioning power. Not only is the BRC about funding, it is also about providing intellectual conversation about design and the work of its members so that there are people to discuss, debate, and cultivate design work in and about the Black diaspora.

Interview by Drew Zeiba

Video portrait by David Hartt

Editing by Jessica Lin

Music by King Britt presents Moksha Black

A PIN–UP production in partnership with Thom Browne

This video is part of a series of ten portraits David Hartt created for PIN–UP on the occasion of Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America at the Museum of Art (Feb 20–May 31, 2021), curated by Mabel O. Wilson and Sean Anderson. The portraits were also published in the print edition of PIN–UP 29.