INTERVIEW: BOFFO Founder Faris Al-Shathir on 10 Years of Diversity and Art in Fire Island

Fire Island Pines feels like an impossible place: a gay idyll spitting distance from New York City; a small community located on an ice-age formation of sand, pine, and shadblow trees, as thin and evanescent as a line of cocaine, populated by carless pleasure seekers and their modernist palaces. It was here that I met Faris Saad Al-Shathir in 2015, and while I can’t remember where we met — was it architect Charles Renfro’s pool? Or on the deck of the Pavilion at night? Or on the beach in front of the Meat Rack? — I do remember that he seemed to know the place better than almost anyone. Just a few years before, BOFFO, the arts organization that Al-Shathir founded in 2009, had established an artist residency there (and later an annual performance festival) that quickly reshaped the cultural topography of the island. Historically Fire Island’s communities like the Pines and nearby Cherry Grove have been a refuge for queer artists for nearly a century, from the 1930s dune frolics of PaJaMa (Paul Cadmus, Jared French, and Margaret Hoening) to the disco-era decadence of Halston and Robert Mapplethorpe. Since the 1980s, however, the Pines especially became increasingly homogeneous, a glamorous retreat for white “circuit queens” and hypermasculine muscle gays. With his boyishly good looks and gym-toned body, Al-Shathir, a first-generation Iraqi-American and a trained architect, is at once both the ultimate insider and outsider in this terrain. In his multiple roles as founder, main fundraiser, and creative director, Al-Shathir has used BOFFO’s program to bring a diverse range of artists to the Pines who may not have otherwise felt welcome there. On the occasion of BOFFO’s 10-year anniversary he reflected on his years in Fire Island, and the challenges his organization faces in its efforts to reclaim the Pines as an inclusive queer space of creative possibility.

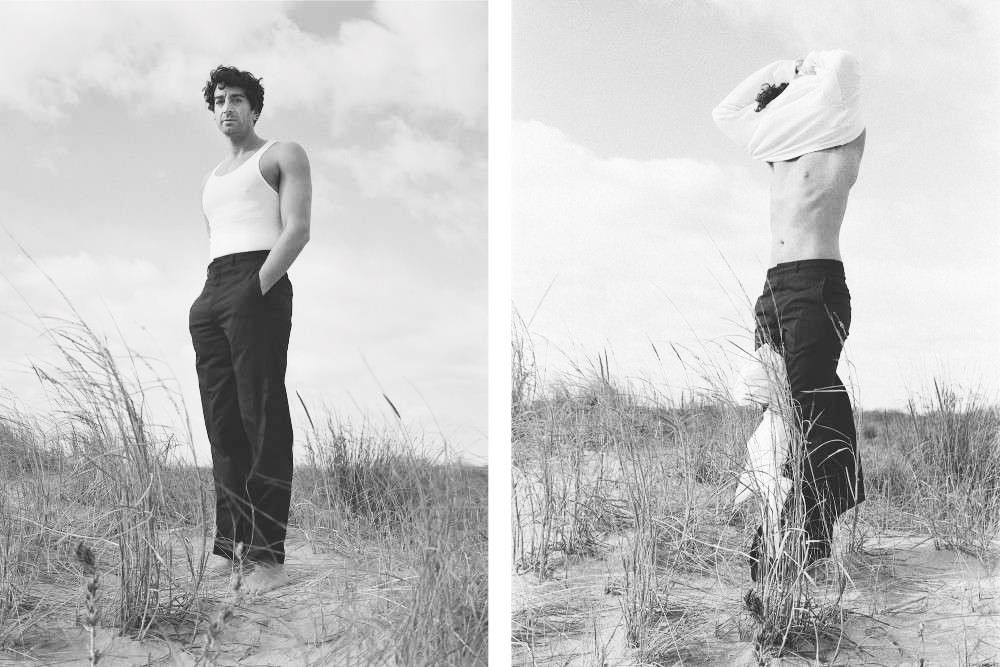

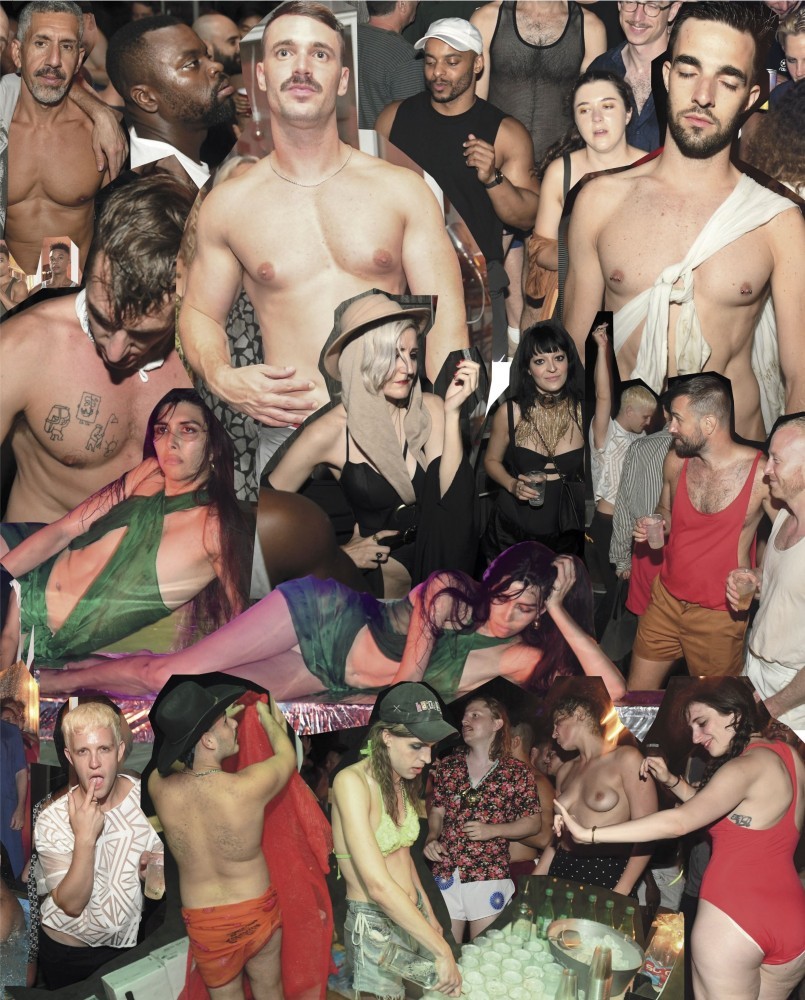

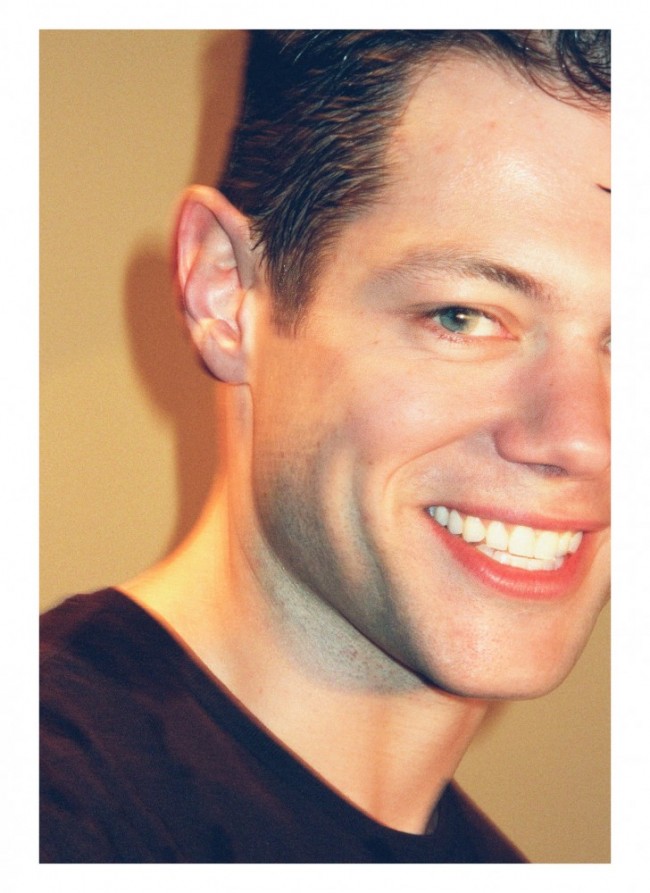

BOFFO founder and trained architect Faris Saad Al-Shathir photographed by Benjamin Fredrickson for PIN–UP.

Evan Moffit: Can you tell me about the first time you visited Fire Island and how you fell in love with it?

Faris Saad Al-Shathir: It was around 2010. I had been in New York just under two years, and had heard that Fire Island was a gay beach destination, so I made a day trip with a friend, not knowing what to expect, not even really knowing that there were no cars there. I immediately fell in love with its beauty. I popped around to a bunch of house parties, drank a lot, and specifically remember a hot tub make-out experience. Waiting for the train to get back to the city I remember thinking, “I can’t believe that place exists.”

When you started BOFFO that same year, it wasn’t based in Fire Island. How did the program begin?

BOFFO was cofounded by myself and Gregory Sparks. We met in grad school at UPenn, when I was studying architecture and he was studying landscape architecture. One day we went to the Museum of Art and Design and saw this really mediocre exhibition, and thought, “Wow we could definitely do something a lot better than that.” I had past experience organizing exhibitions for the American Institute of Architects and the Slot Foundation in Philadelphia, where I produced a big Vito Acconci exhibit and a few smaller projects. While I was at UPenn, I had started organizing end of year exhibitions for the entire school of design, which includes fine art, architecture, landscape, historic preservation, and city planning, so I had developed an interest in exhibition formats as a way of exploring new subjects and bringing people together.

The first BOFFO project was a short residency and big exhibition in Brooklyn Heights on the waterfront, in one of the old Jehovah’s Witnesses buildings. We had a relationship with a developer there, and he gave us all the ground floor space as the park beside it was being constructed. We gave that over to artists to make work. The second floor of that building, a former printing press, was 15,000 square feet with big skylights. We mounted an exhibition in that space with about 150 different artists.

-

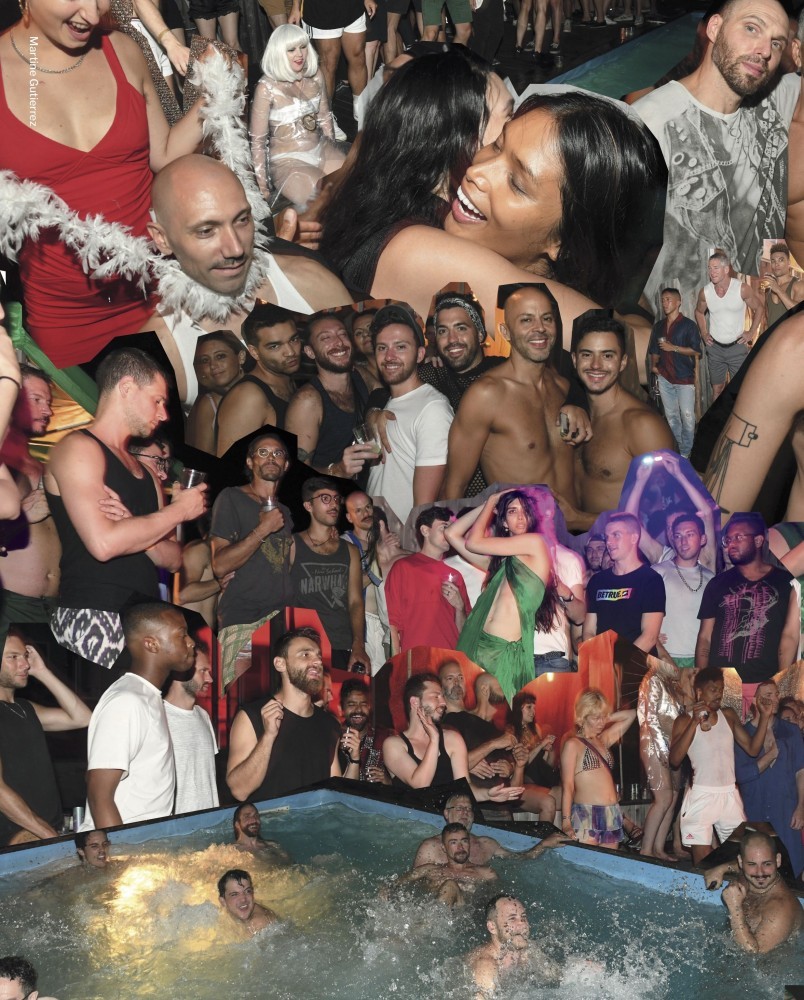

Jeremy O. Harris and cast performing a scene from Water Sports; or Insignificant White Boys a play he adapted and performed during his BOFFO residency in 2019. Photography by Matthew Leifheit.

-

Jeremy O. Harris and cast performing a scene from Water Sports; or Insignificant White Boys a play he adapted and performed during his BOFFO residency in 2019. Photography by Matthew Leifheit.

-

Jeremy O. Harris and cast performing a scene from Water Sports; or Insignificant White Boys a play he adapted and performed during his BOFFO residency in 2019. Photography by Matthew Leifheit.

-

Jeremy O. Harris and cast performing a scene from Water Sports; or Insignificant White Boys a play he adapted and performed during his BOFFO residency in 2019. Photography by Matthew Leifheit.

What was the language that you used to describe BOFFO then? Was it a curatorial platform?

It was more of an artist project platform with a nomadic model. It wasn’t really about specific places, but rather about showing artists’ work in unconventional places, and it always had an experimental or transgressive bent to it. We were focused on avant-garde or boundary-pushing practices that could engage with and benefit communities.

As an organization, we curate through a pretty open methodology. It’s not stiffly defined, in that we’ve curated in partnership with other curators, we’ve curated through artist-driven curatorial projects. We’ve used competitions to bring in new artists. New BOFFO residents are nominated by past residents, so everyone is involved in selecting artists, and we as an organization work closely with them to make their projects real. As we develop new projects and new conceits, we’re constantly re-evaluating what the best way is to curate and be engaged.

-

Young Boy Dancing Group at the BOFFO Fire Island Performance Festival in August 2019. Photography By Nir Arieli.

-

West Dakota performing during “Papi Juice on the Beach” at the BOFFO Fire Island Performance Festival in August 2019. Photography by Nir Arieli.

-

-

Xander Gaines performing in Richard Kennedy’s piece for the BOFFO Fire Island Performance Festival in August 2019. Photography By Nir Arieli.

When you first started BOFFO, you were also thinking, probably more so than your average art historian or fledgling curator, about the urban landscape — exhibitions in the expanded field.

Yeah, I like to think about problem-solving effects — about effects on larger discourse, on communities, and about how to create change. That’s a very architecture way of thinking; I think architects are taught to be problem-solving. There’s always been a really specific community bent to our work.

Where did the name for BOFFO come from?

It’s an English word, meaning “great success.” Greg found the word flipping through a dictionary. The etymology of the term is somewhat blurry, but it was used after the Great Depression to describe a birth of creative success. We started the organization during the recession in 2009; I had moved to New York just after Lehman Brothers crashed and couldn’t find work in architecture. Greg and I needed to stay busy, so we decided to start this side project to bring people together and engage with New York City in a more meaningful way

I love how you set great expectations for yourself with your name.

It’s been interesting to talk to people about the term success. Everybody defines success so differently. It has such great aspiration, but it’s also very open-ended.

-

Young Boy Dancing Group at the BOFFO Fire Island Performance Festival in August 2019. Photography By Nir Arieli.

-

Ryan McNamara and dancers during the BOFFO Fire Island Performance Festival in August 2019. Photography by Nir Arieli.

-

Dancers executing Ryan McNamara’s piece for the BOFFO Fire Island Performance Festival in 2019. Photography by Nir Arieli.

When you first started doing programming in Fire Island, did you feel you were meeting a specific need of the community in the Pines? Or was it just serendipity?

In the spring of 2012, we did a project in an old schoolhouse on Madison Street in the Lower East Side. Its auditorium was lent to us by a developer, Michael Bolla, who planned to turn the building into condos. It was a really big project and brought a lot of people into the space. Michael overheard me talking about Fire Island and told me he had a house in the Pines he hadn’t been using for a few years. He said, “I’ve kind of become disenchanted with the community — it’s become a one-note place.” At the time, it didn’t really feel like my community was going out to Fire Island, so that spurred a conversation about what Fire Island was lacking, specifically a diverse creative community — not just in terms of racial diversity but diversity of perspective, body types, and the entire LGBTQ spectrum. It wasn’t much of a place for anybody besides white gay men. So, we wrote a proposal to create this residency that was very specific in its purpose to nurture artists and have artists giving back to the community through public programming. The term “creative placemaking,” which has become pretty popular now, is often used to describe this practice, and I think a lot of what we’re doing is along the same lines.

That first summer, K8 Hardy, Ryan McNamara, T.M. Davy, and Paul Sepuya all came out. Cay Sophie Rabinowitz helped curate — she was the one who introduced us to K8 and Ryan. Michael’s house was partially under construction, so it felt like we were squatting; there was no furniture, so we had to buy mattresses and put up a curtain as a bathroom door. We only had about $5,000 for the whole summer. We collected so much junk from the boardwalk. That summer we met Chris Bogia, who had just started the Fire Island Artist Residency the year before in Cherry Grove, so it definitely felt like something was brewing.

The BOFFO house in the Pines in 2012, the first year of programming in Fire Island. Photography by Faris Saad Al-Shathir.

The Pines, as a development, dates back to the late 1960s, and has historically been a cis, white, gay, upper middle-class male space. More broadly speaking, though, Fire Island has a rich and varied queer artistic history. Some of the creative placemaking that BOFFO artists have engaged in has tapped into that history. Has that become a more important part of the program over the years?

I’m obsessed with the art history of Fire Island. One of my dream projects is to do a publication and an exhibition that fully dives into that history, because it’s been told in bits and pieces, but never that thoroughly. It’s always been queer and experimental; it’s always been a place where art and social practice come together. PaJaMa is one of the earliest examples of an artist collective doing work out there, and that work is pretty visible now. Mapplethorpe, Warhol, Truman Capote and Frank O’Hara also all spent time out here. But there’s so much history that hasn’t been told. We’ve done some research and have started to work on a timeline. As we move forward, I think it’s important that this history gets told. It can inform a lot of artists who continue to practice out there.

You went from visiting Fire Island for day trips to spending the whole summer. Have you learned anything specific from living for such long stretches with artists?

This was the first year that I lived in Fire Island for the entire summer. I always had other jobs because I could never support myself from BOFFO, so I would always spend the week in the city working on other things, and then come out to the island on the weekends and live with the artists. Fire Island offers a kind of community that doesn’t exist in other places, because of the amount of intimate time you spend with people. It’s a really easy place to develop relationships. It’s been such a pleasure developing those relationships with so many different artists by living and working together. But everything has been so much harder since 2016, in terms of managing collective anxieties and interpersonal struggles.

-

Talking To The Sun At Fire Island, a journal published by BOFFO and designed by Jerome Harris. The journal documented a year’s worth of residencies and performances on Fire Island during the summer of 2018.

-

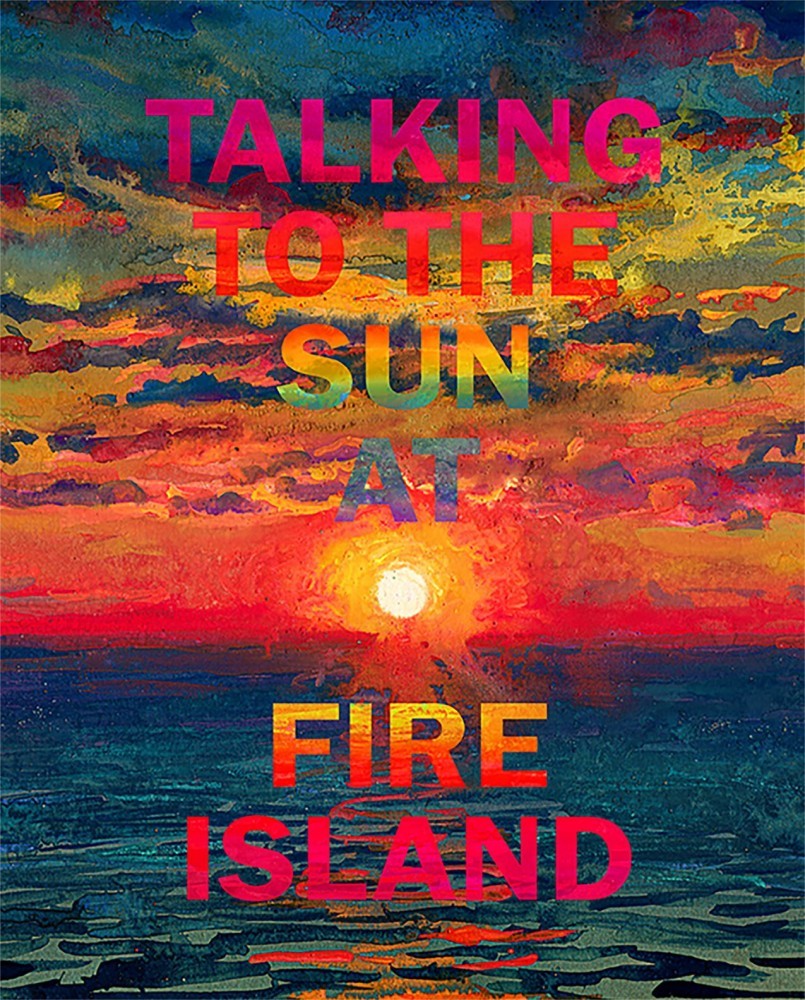

Collage from Talking to the Sun at Fire Island (2019) a journal published by BOFFO to document its residencies and performances on Fire Island in the summer of 2018. Courtesy BOFFO.

-

Collage from Talking to the Sun at Fire Island (2019) a journal published by BOFFO to document its residencies and performances on Fire Island in the summer of 2018. Courtesy BOFFO.

That’s interesting. You mean specifically because of Trump’s election in 2016?

I really noticed artists struggling with the insecurity of what it means to make work during Trump’s presidency. We were on the defensive so much more. Fighting for what you believe in means constantly being on edge, especially if you’re queer or trans, and your community has been under attack almost daily. The collective toll that’s taken, and the way that’s reflected in artists’ practice and artists’ living, has been really noticeable. There’s this current political rhetoric around healing, and it sounds so cheesy, but actually I do believe in it. I can think of so many times over the past four years when we’ve worked with artists who were having a really hard time, and Fire Island could be a place for them to heal.

-

Promotional materials to promote the Telfar pop-up store in Fire Island, Summer 2016. Photography courtesy Telfar.

-

Promotional materials to promote the Telfar pop-up store in Fire Island, Summer 2016. Photography courtesy Telfar.

I wanted to ask you about your neighbors. I don’t know who, if anyone, voted for Trump, but because it is such a rich, white male space, have you experienced any resistance from them? What has that looked like?

It’s been difficult. There has been significant resistance to our work on Fire Island from the beginning. For a long time, I simply felt grateful to be able to exist and work out there, but this summer I felt frustrated about how passively we responded to specific incidents in the past, particularly around race. For example, in 2017, we had a Telfar pop-up in the harbor, where Telfar showed some mannequins with swimsuits and some other work he made with Frank Benson and Lizzie Fitch. As it got installed in the harbor, some residents didn’t like the way that it looked, and they didn’t like the crowd that was showing up, so they started complaining. Eventually the guy who gave us permission to be in the harbor started sending all these crazy, aggressive texts, saying “You guys need to leave the harbor” and “This is not what was approved” and “It looks like KMART.” Telfar and a number of others were approached and verbally assaulted. It wasn’t ever physical, but it got really intense. Looking back, we should have made it clear to the entire community what was happening. It just feels unfortunate that we didn’t do more.

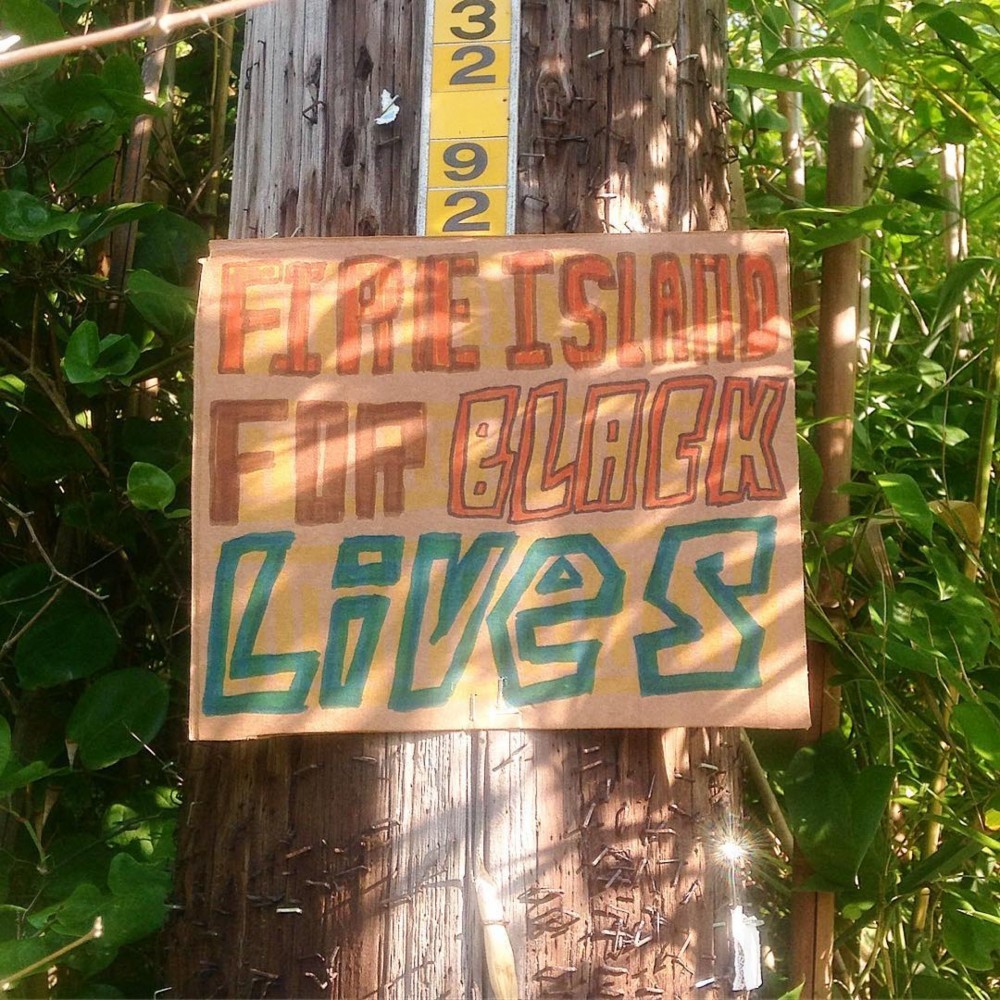

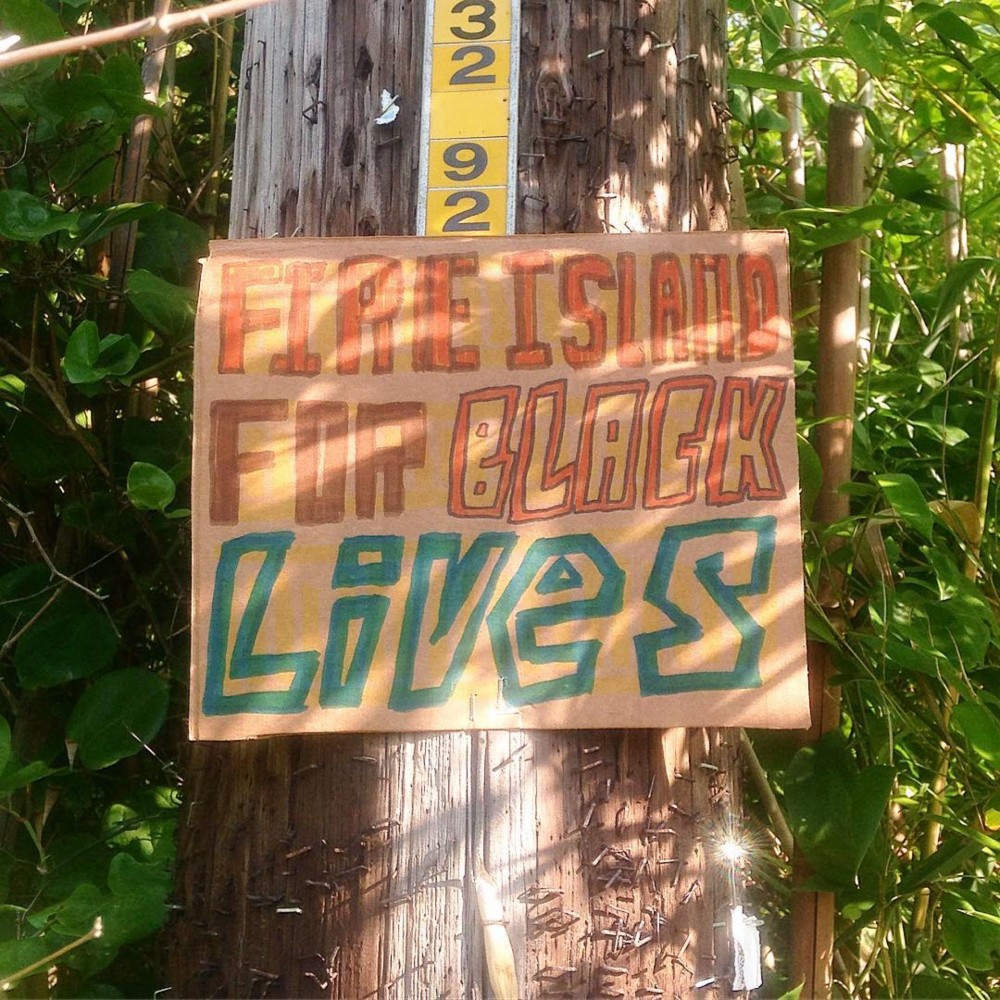

There have been other incidents. In 2016, Morgan Bassichis tried to install Black Lives Matter posters in the harbor and around the community, and they were all torn down within hours. It wasn’t really until this year that people have come around to the idea that having artists of color — and people of color — in Fire Island is actually a good thing. Somebody recently asked me, “What did you expect? What white communities in the United States do you know that have actively and warmly welcomed a number of Black people to come in and move into their neighborhoods?” It’s this historic American problem, and there are examples all over of what predominately white communities have done when people of color have moved in. For whatever reason, I didn’t believe it or didn’t see it, and was being told by enough people that they had our backs. But actions speak louder than words.

-

During their BOFFO residency, artist Morgan Bassichis together with collaborators created Black Lives Matter signs and posted them around Fire Island.

-

During their BOFFO residency, artist Morgan Bassichis together with collaborators created Black Lives Matter signs and posted them around Fire Island.

-

During their BOFFO residency, artist Morgan Bassichis together with collaborators created Black Lives Matter signs and posted them around Fire Island.

-

During their BOFFO residency, artist Morgan Bassichis together with collaborators created Black Lives Matter signs and posted them around Fire Island.

When you’re faced with that kind of resistance, what kind of recourse do you have? Do you go to the Fire Island Pines Property Owners’ Association meetings? How do you advocate for BOFFO and its residents?

After George Floyd’s death, suddenly every organization and corporation was like, “We have to do something about diversity.” People were looking for ways to defend Fire Island as diverse, and they could point to BOFFO and be on the right side of history. All of a sudden, we got recognition for the work that we had been doing for so many years. The Pines has since created a Black Equality Committee to address issues around diversity on the island. I am optimistic about that and think it is an important step. We tried to get them to do diversity training three years ago, and they rejected the concept whenever we proposed it, but it’s better late than never. And that said, it’s not like our work hasn’t been supported. Art dealer Brent Sikkema has championed our work for a long time. There have been community members, some of them in leadership, who have gone out of their way to really understand. But it hasn’t felt like a collective, warm, loving experience. We’ve also struggled to grow the organization because, despite having the residency in place, we’ve had to bring in most of our funding over the past ten years from New York City. Only a tiny fraction has come from Fire Island.

Another key part of the Pines community are the “circuit queens.” Do you feel that community will always be separate from the one you’ve been building?

I love the idea of interacting and engaging with that audience, whether or not they care about what we do. We’ve never compromised in order to reach that audience, which is what it would require, but given our persistence, people have started to pay more attention. In 2019, Carlos Motta, John Arthur Peetz, and their SPIT! (Sodomites, Perverts, Inverts Together!) collective performed the Faggot Manifesto on the sunset dock. It was amplified, so the manifesto reverberated throughout the Pines. People were really triggered — they didn’t understand why terms like “faggot” were being used — which was surprising for a work made specifically for queer people and presented in a historic queer community. Ultimately, it felt successful because, by complaining, people were forced to engage with the work, ask questions, and try to understand its intention.

-

Camilo Godoy preforming a SPIT! Manifesto during the BOFFO Fire Island Performance Festival in August 2019. Photography by Nir Arieli.

-

Vivian Crockett performing a SPIT! Manifesto during the BOFFO Fire Island Performance Festival in 2019. Photography by Nir Arieli.

You were talking earlier about the attitude changing towards the Black Lives Matter movement. You had a very ambitious year planned, and then Covid-19 forced you to make a lot of changes. Did BOFFO rethink its strategy in light of the pandemic? Did the artists rethink their work?

We got pretty lucky. The fact that we have private accommodations for our artists allowed it to feel Covid safe. Most of our work has always been presented outdoors. Artists were excited to be on Fire Island and present work when nothing else was happening. It was also really clear, especially during the protests, that people needed a place to recover and feel nurtured. It felt really great to provide that opportunity and just to give everyone the ability to think and use their art practice to process.

What’s next for BOFFO? Are you still trying to take over that house in the Meat Rack?

We grew our board this year, and everybody wants to provide more resources for our artists. We don’t currently have a real studio space, so we’re looking into acquiring space that could accommodate painters, sculptors, and other artists to practice more mediums more comfortably. We want to give artists more money, more time, better accommodation. We’re looking for more permanence out there, shifting from rentals to ownership of the space where the residency takes place. We’re also really interested in exploring exhibition formats and art center concepts, so that there are easier ways for us to share work. The dream is to take over Carrington House, at the edge of the Meat Rack. Truman Capote wrote Breakfast at Tiffany’s there. Lincoln Kirstein and Katharine Hepburn spent time there. It’s great to think of a space that has historically supported artists can be that again.

Interview by Evan Moffitt

Portraits by Benjamin Fredrickson for PIN–UP