INTERVIEW: Eugene Tssui, Architect, Fashion Designer, Gymnast, and Energy Warrior

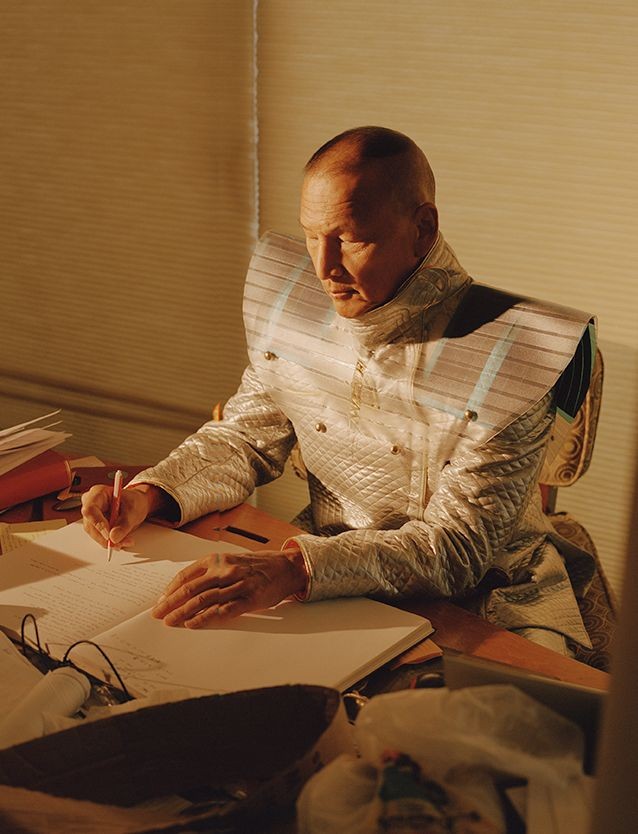

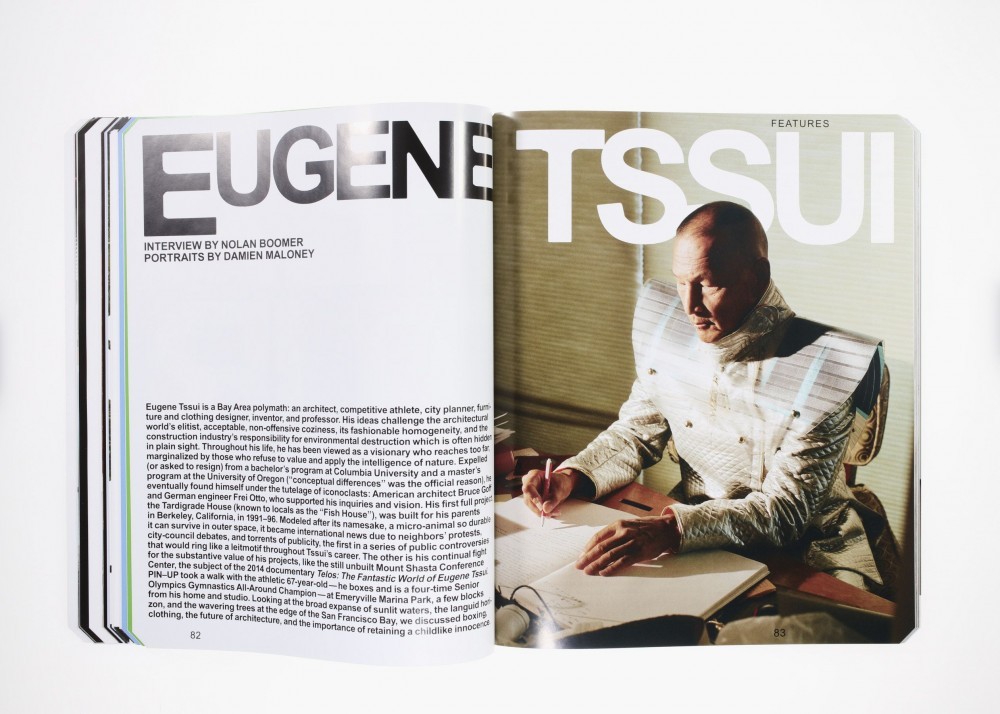

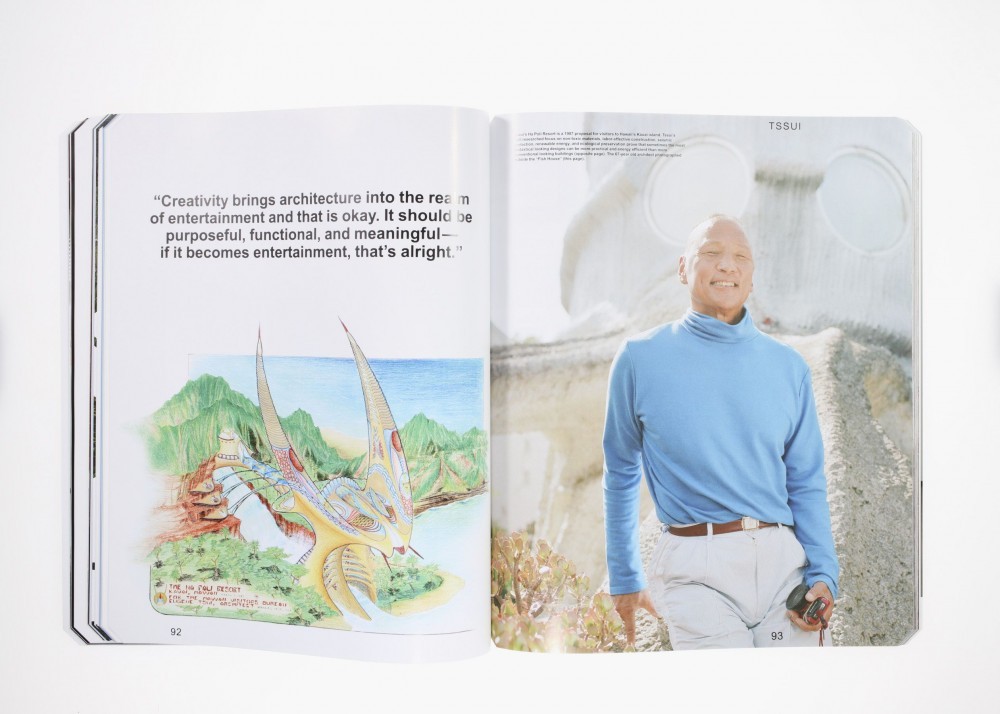

Eugene Tssui is a Bay Area polymath: an architect, competitive athlete, city planner, furniture and clothing designer, inventor, and professor. His ideas challenge the architectural world’s elitist, acceptable, non-offensive coziness, its fashionable homogeneity, and the environmental destruction and the construction industry’s responsibility for environmental destruction which is often hidden in plain sight. Throughout his life, he has been viewed as a visionary who reaches too far, marginalized by those who refuse to value and apply the intelligence of nature. Expelled (or asked to resign) from a bachelor’s program at Columbia University and a master’s program at the University of Oregon (“conceptual differences” was the official reason), he eventually found himself under the tutelage of iconoclasts: American architect Bruce Goff and German engineer Frei Otto, who supported his inquiries and vision. His first full project, the Tardigrade House (known to Berkeley locals as the “Fish House”), was built for his parents in Berkeley, California, in 1991–96. Modeled after its namesake, a micro-animal so durable it can survive in outer space, it became international news due to neighbors’ protests, city-council debates, and torrents of publicity, the first in a series of public controversies that would ring like a leitmotif throughout Tssui’s career. The other is his continual fight for the substantive value of his projects, like the still unbuilt Mount Shasta Conference Center, the subject of the 2014 documentary Telos: The Fantastic World of Eugene Tssui. PIN–UP took a walk with the athletic 67-year-old — he boxes and is a four-time Senior Olympics Gymnastics All-Around Champion — at Emeryville Marina Park, a few blocks from his home and studio. Looking at the broad expanse of sunlit waters, the languid horizon, and the wavering trees at the edge of the San Francisco Bay, we discussed boxing, clothing, the future of architecture, and the importance of retaining a childlike innocence.

-

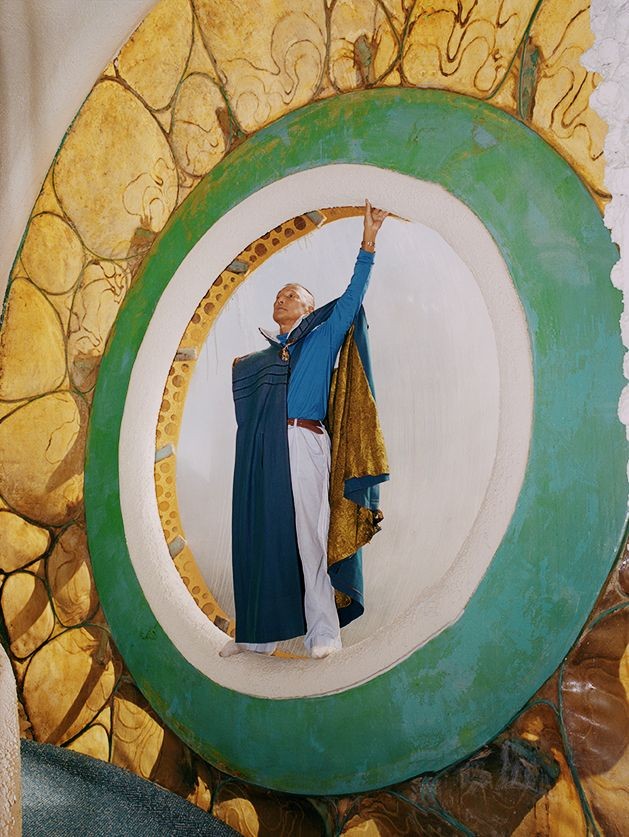

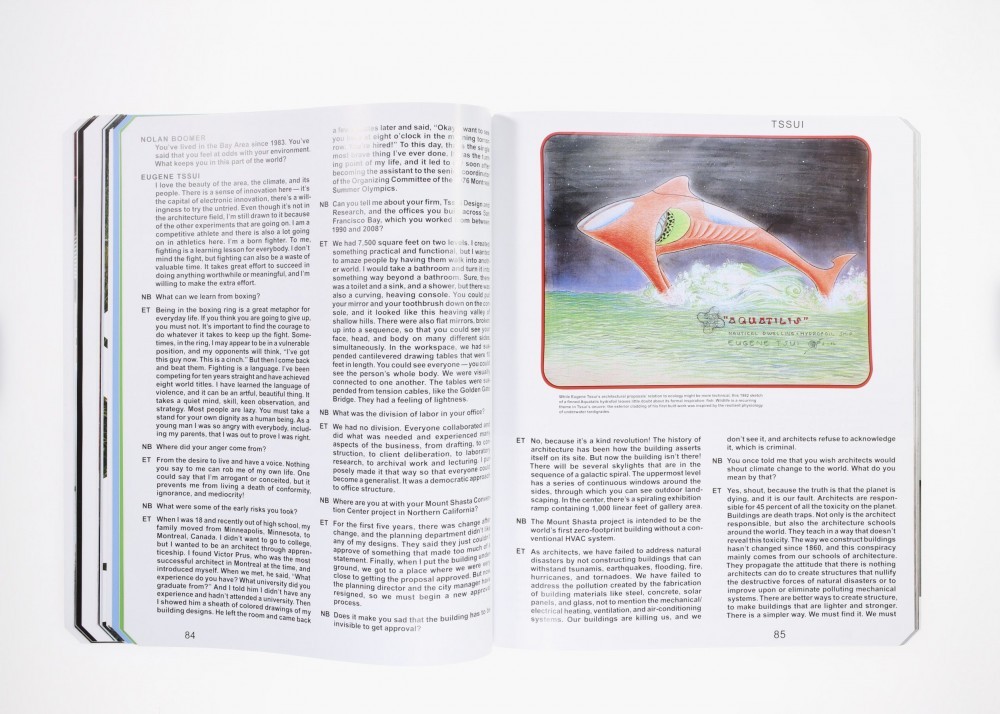

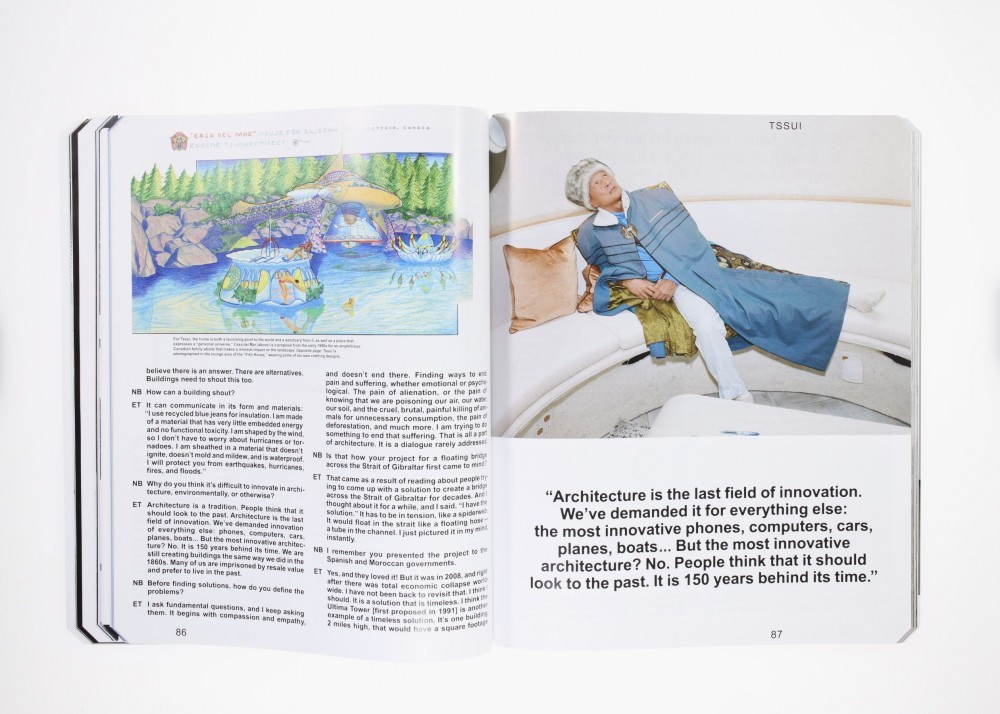

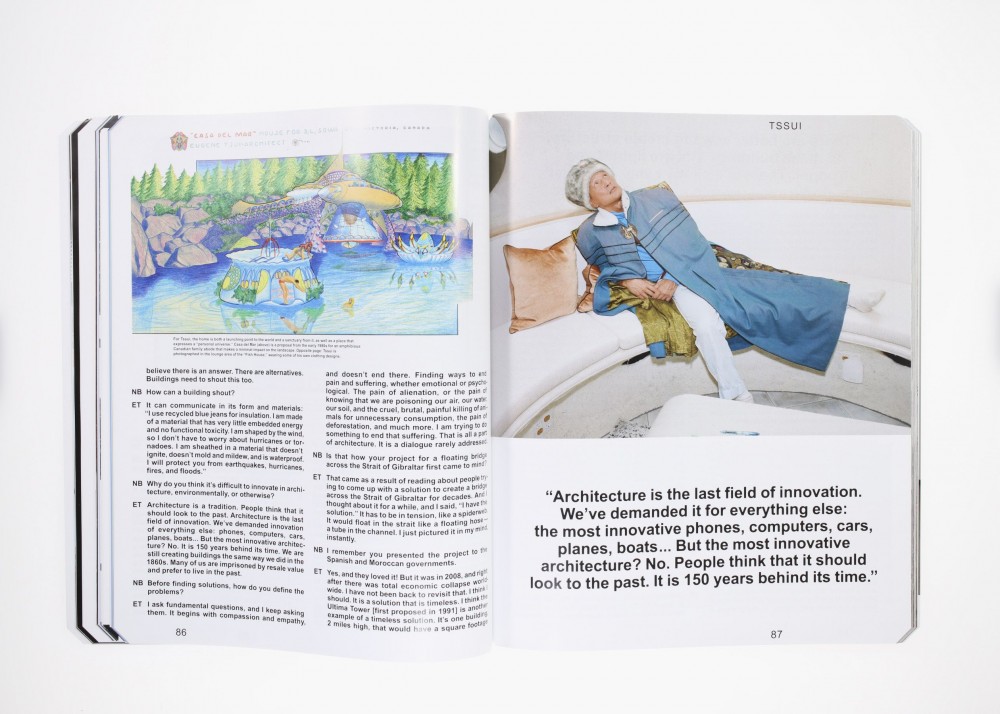

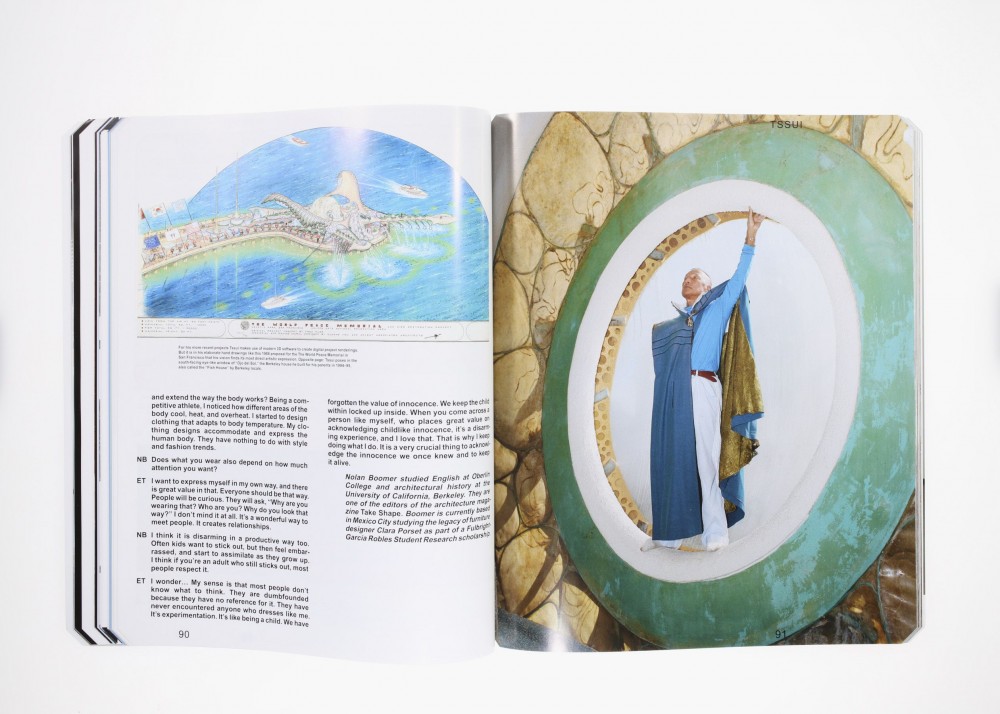

Eugene Tssui photographed by Damien Maloney for PIN–UP 31, Fall Winter 2021/22.

-

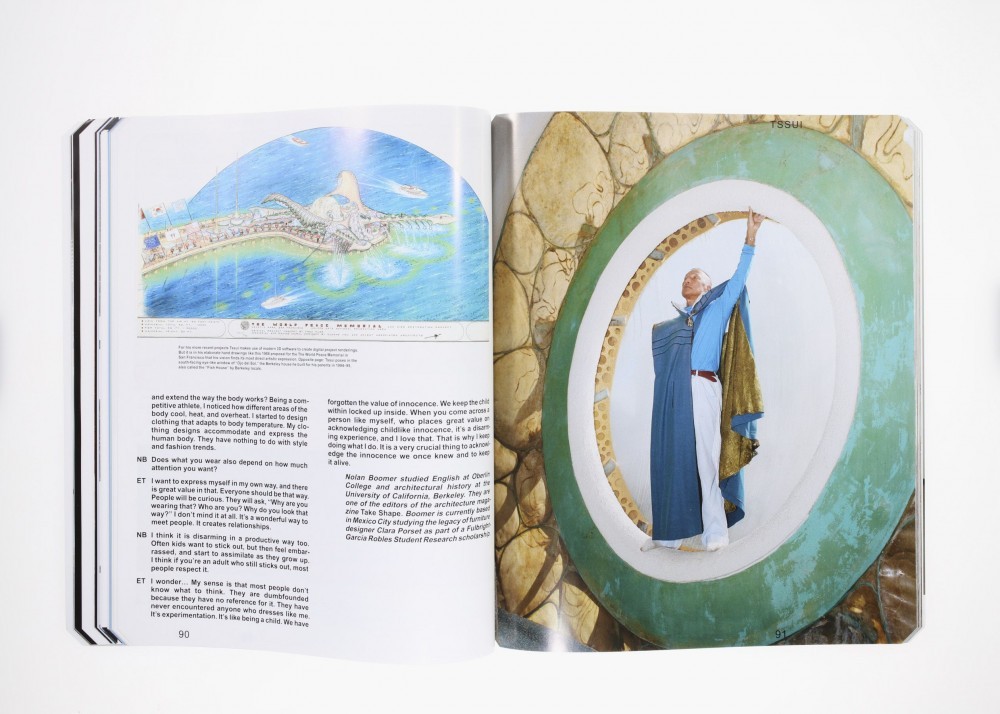

Eugene Tssui in the print edition of PIN–UP 31, Fall Winter 2021/22. Art Direction by Office Ben Ganz.

Nolan Boomer: You’ve lived in the Bay Area since 1983. You’ve said that you feel at odds with your environment. What keeps you in this part of the world?

Eugene Tssui: I love the beauty of the area, the climate, and its people. There is a sense of innovation here — it’s the capital of electronic innovation, there’s a willingness to try the untried. Even though it’s not in the architecture field, I’m still drawn to it because of the other experiments that are going on. I am a competitive athlete and there is also a lot going on in athletics here. I’m a born fighter. To me, fighting is a learning lesson for everybody. I don’t mind the fight, but fighting can also be a waste of valuable time. It takes great effort to succeed in doing anything worthwhile or meaningful, and I’m willing to make the extra effort.

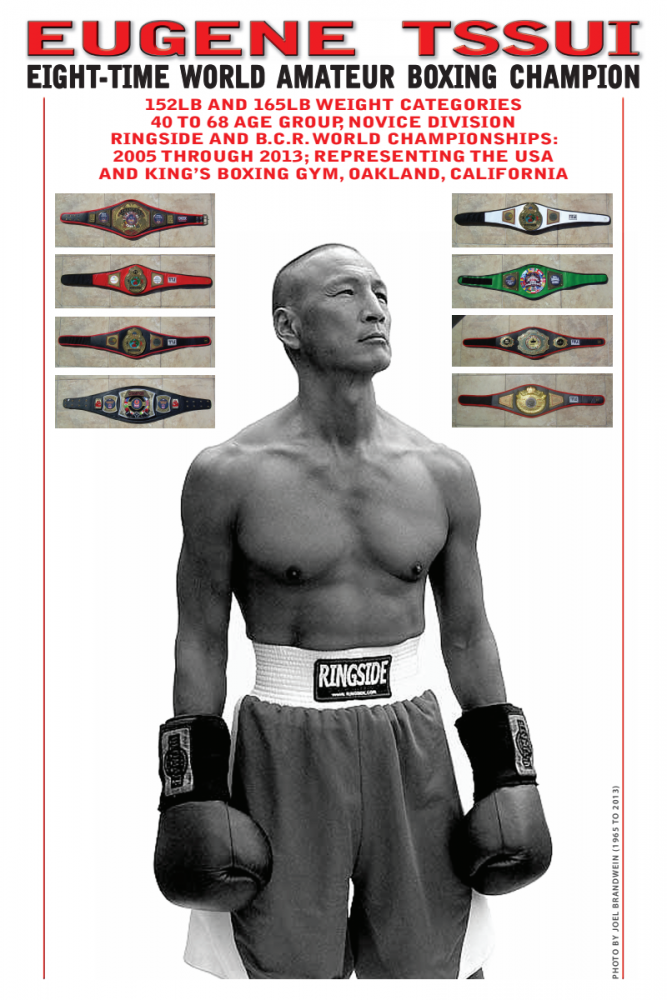

What can we learn from boxing?

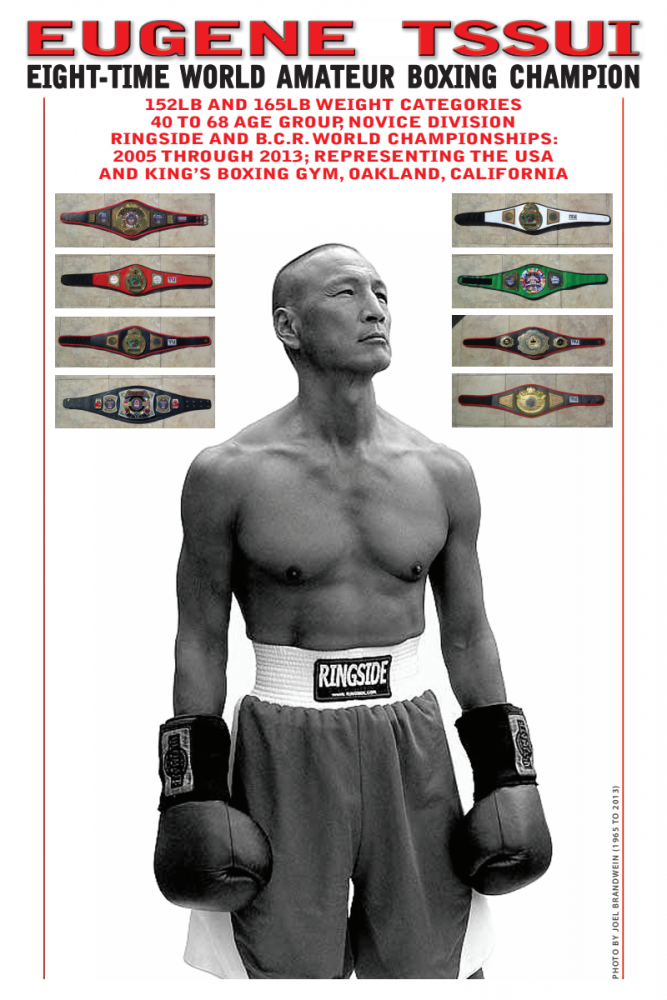

Being in the boxing ring is a great metaphor for everyday life. If you think you are going to give up, you must not. It’s important to find the courage to do whatever it takes to keep up the fight. Sometimes, in the ring, I may appear to be in a vulnerable position, and my opponents will think, “I’ve got this guy now. This is a cinch.” But then I come back and beat them. Fighting is a language. I’ve been competing for ten years straight and have achieved eight world titles. I have learned the language of violence, and it can be an artful, beautiful thing. It takes a quiet mind, skill, keen observation, and strategy. Most people are lazy. You must take a stand for your own dignity as a human being. As a young man I was so angry with everybody, including my parents, that I was out to prove I was right.

-

Eugene Tssui in the print edition of PIN–UP 31, Fall Winter 2021/22. Art Direction by Office Ben Ganz.

-

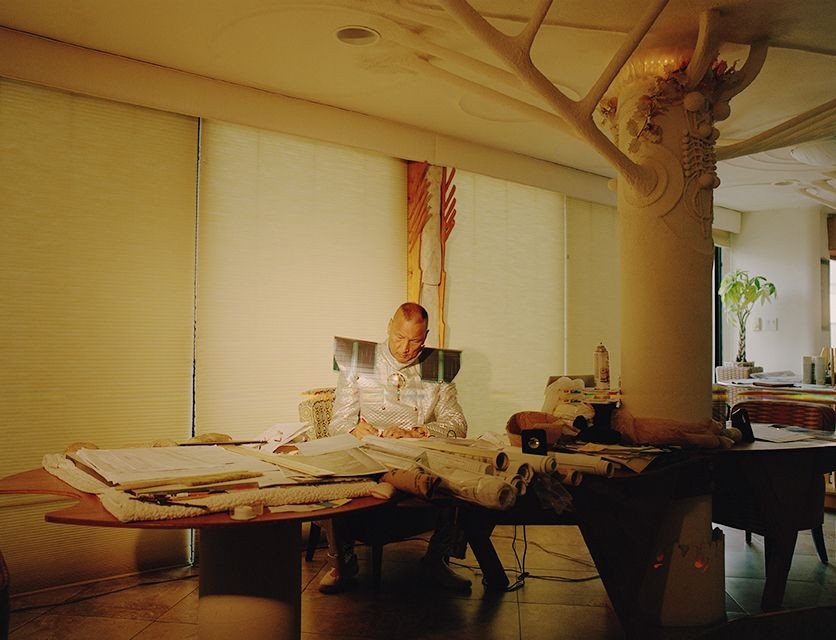

Eugene Tssui photographed in his Berkeley office by Damien Maloney for PIN–UP 31, Fall Winter 2021/22.

Where did your anger come from?

From the desire to live and have a voice. Nothing you say to me can rob me of my own life. One could say that I’m arrogant or conceited, but it prevents me from living a death of conformity, ignorance, and mediocrity!

What were some of the early risks you took?

When I was 18 and recently out of high school, my family moved from Minneapolis, Minnesota to Montreal, Canada. I didn’t want to go to college, but I wanted to be an architect through apprenticeship. I found Victor Prus, who was the most successful architect in Montreal at the time, and introduced myself. When we met, he said, “What experience do you have? What university did you graduate from?” And I told him I didn’t have any experience and hadn’t attended a university. Then I showed him a sheath of colored drawings of my building designs. He left the room and came back a few minutes later, and said, “Okay, I want to see you here at eight o’clock in the morning tomorrow. You’re hired!” To this day, that’s the single most brave thing I’ve ever done. It was the turning point of my life, and it led to my soon after becoming the assistant to the senior coordinator of the Organizing Committee of the 1976 Montreal Summer Olympics.

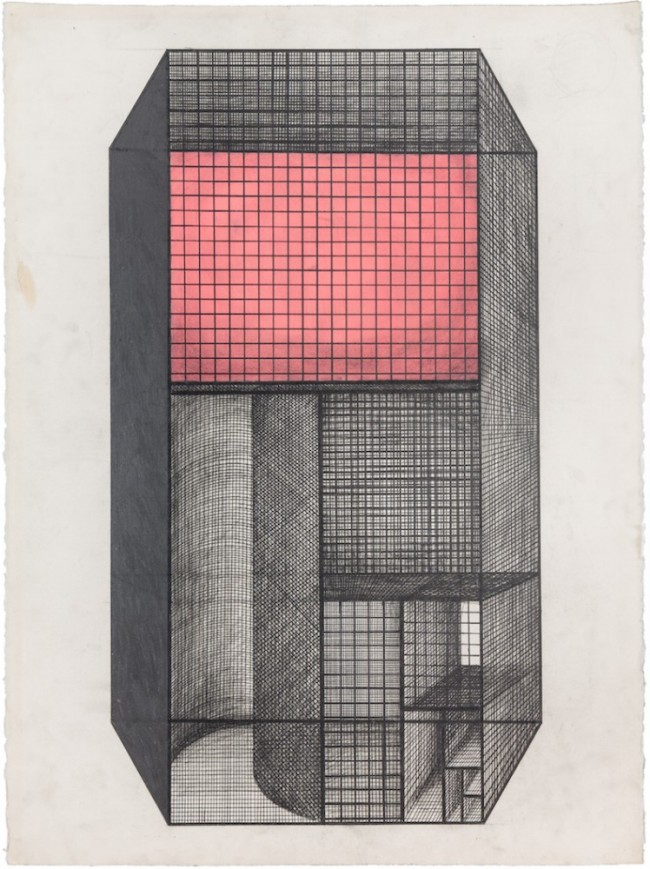

Can you tell me about your firm, Tssui Design and Research, and the offices you built across San Francisco Bay, which you worked from between 1990 and 2008?

We had 7,500 square feet on two levels. I created something practical and functional, but I wanted to amaze people by having them walk into another world. I would take a bathroom and turn it into something way beyond a bathroom. Sure, there was a toilet and a sink, and a shower, but there was also a curving, heaving console. You could put your mirror and your toothbrush down on the console, and it looked like this heaving valley of shallow hills. There were also flat mirrors, broken up into a sequence, so that you could see your face, head, and body on many different sides, simultaneously. In the workspace, we had suspended, cantilevered drawing tables that were 10 feet in length. You could see everyone — you could see the person’s whole body. We were visually connected to one another. The tables were suspended from tension cables, like the Golden Gate Bridge. They had a feeling of lightness.

-

Eugene Tssui photographed in his Berkeley office by Damien Maloney for PIN–UP 31, Fall Winter 2021/22.

-

Eugene Tssui in the print edition of PIN–UP 31, Fall Winter 2021/22. Art Direction by Office Ben Ganz.

What was the division of labor in your office?

We had no division. Everyone collaborated and did what was needed and experienced many aspects of the business, from drafting, to construction, to client deliberation, to laboratory research, to archival work and lecturing. I purposely made it that way so that everyone could become a generalist. It was a democratic approach to office structure.

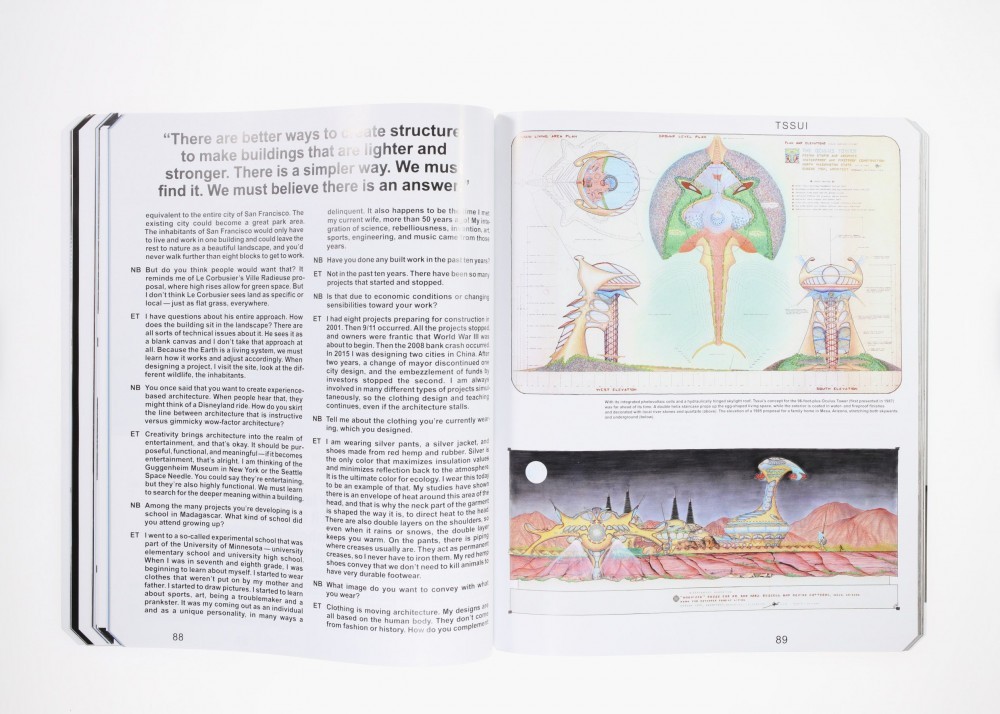

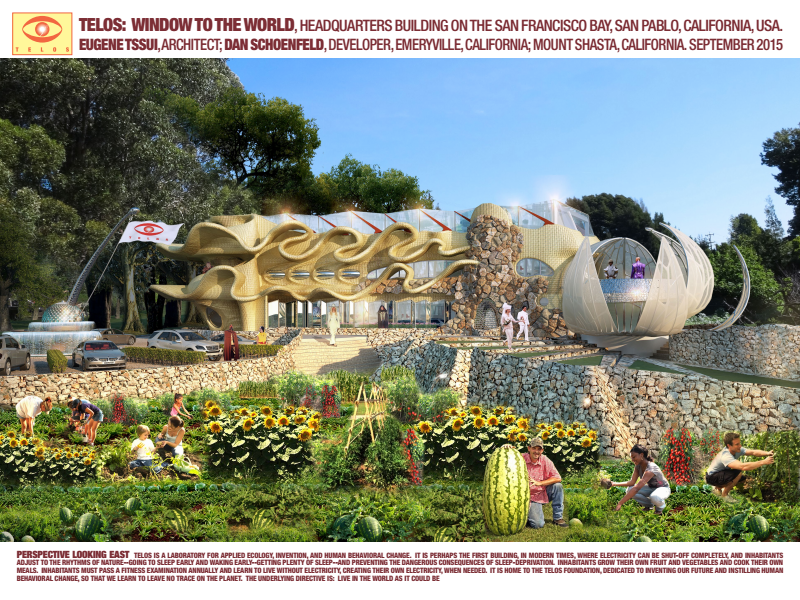

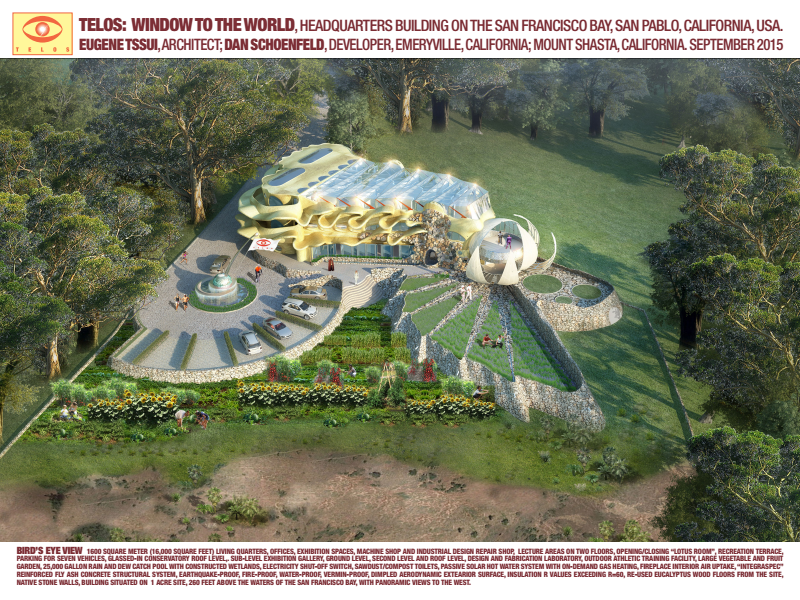

Where are you at with your Mount Shasta Convention Center project in northern California?

For the first five years, there was change after change, and the planning department didn’t like any of my designs. They said they just couldn’t approve of something that made too much of a statement. Finally, when I put the building underground, we got to a place where we were very close to getting the proposal approved. But now, the planning director and the city manager have resigned, so we must begin a new approval process.

-

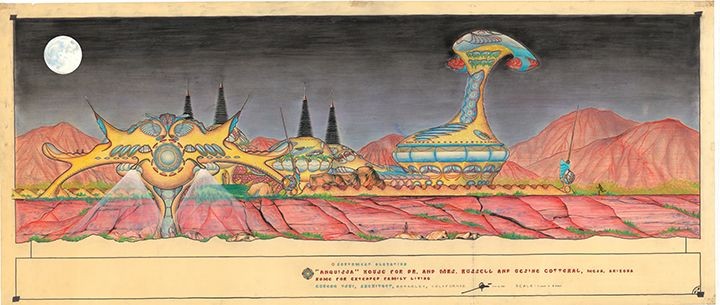

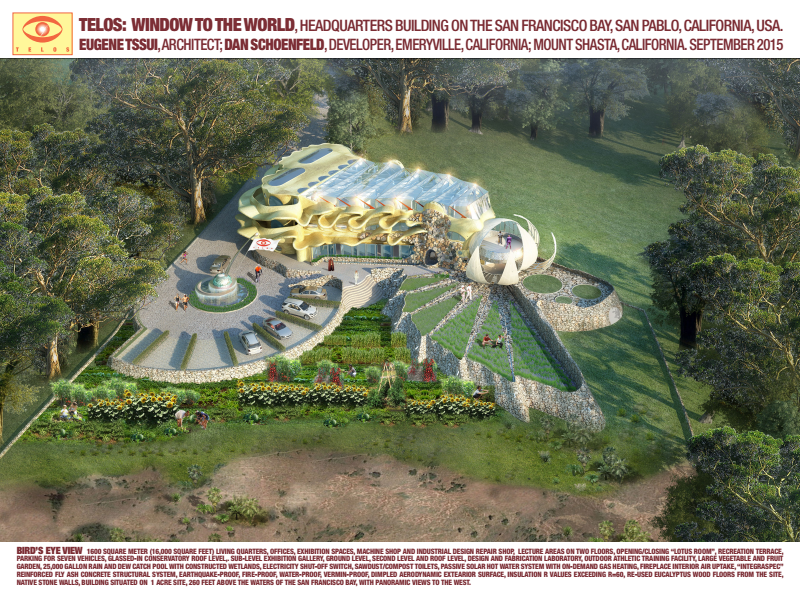

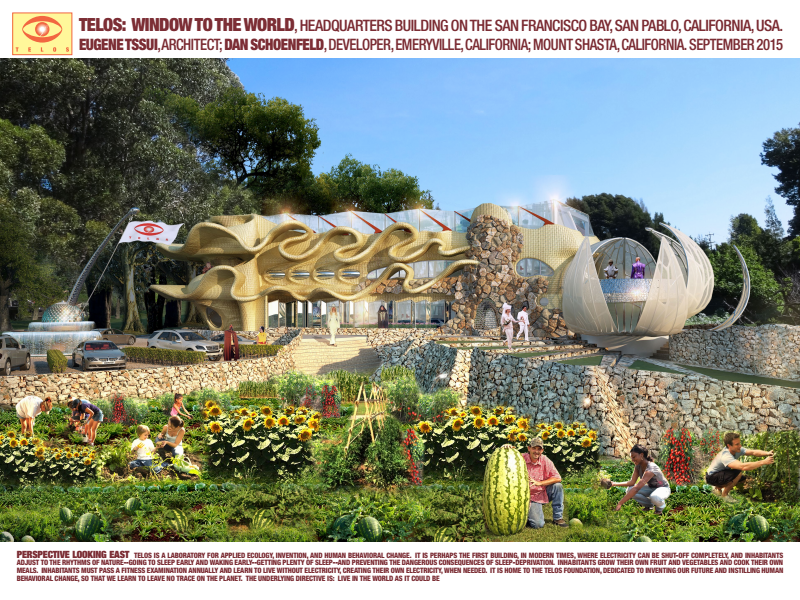

Rendering of Tssui’s Telos building in Mount Shasta, California. Image courtesy of Eugene Tssui.

-

Rendering of Tssui’s Telos building in Mount Shasta, California. Image courtesy of Eugene Tssui.

Does it make you sad that the building has to be invisible to get approval?

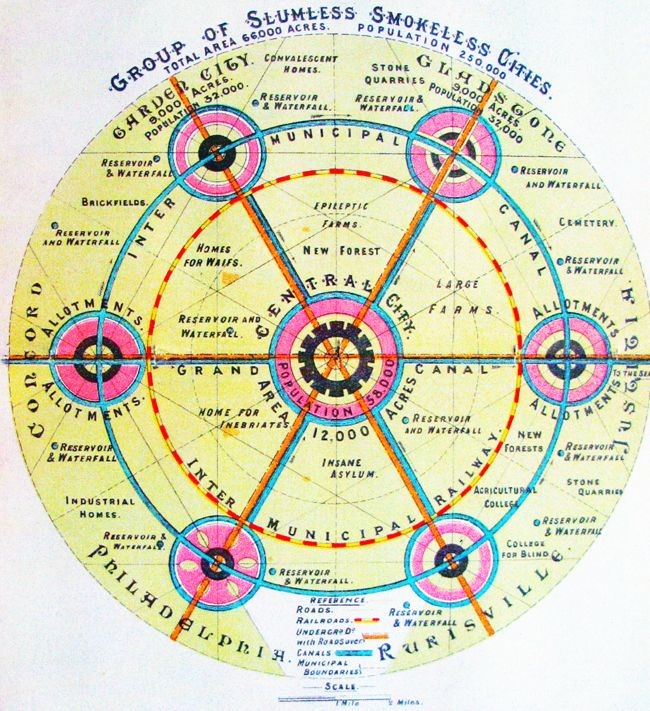

No, because it’s a kind revolution! The history of architecture has been how the building asserts itself on its site. But now the building isn’t there! There will be several skylights that are in the sequence of a galactic spiral. The uppermost level has a series of continuous windows around the sides, through which you can see outdoor landscaping. In the center, there’s a spiraling exhibition ramp containing 1,000 linear feet of gallery area.

The Mount Shasta project is intended to be the world’s first zero-footprint building without a conventional HVAC system.

As architects, we have failed to address natural disasters by not constructing buildings that can withstand tsunamis, earthquakes, flooding, fire, hurricanes, and tornadoes. We have failed to address the pollution created by the fabrication of building materials like steel, concrete, solar panels, and glass, not to mention the mechanical/electrical heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning systems. Our buildings are killing us, and we don’t see it, and architects refuse to acknowledge it, which is criminal.

You once told me that you wish architects would shout climate change to the world. What do you mean by that?

Yes, shout, because the truth is that the planet is dying, and it is our fault. Architects are responsible for 45 percent of all the toxicity on the planet. Buildings are death traps. Not only is the architect responsible, but also the architecture schools around the world. They teach in a way that doesn’t reveal this toxicity. The way we construct buildings hasn’t changed since 1860, and this conspiracy mainly comes from our schools of architecture. They propagate the attitude that there is nothing architects can do to create structures that nullify the destructive forces of natural disasters or to improve upon or eliminate polluting mechanical systems. There are better ways to create structure, to make buildings that are lighter and stronger. There is a simpler way. We must find it. We must believe there is an answer. There are alternatives. Buildings need to shout this too.

-

Eugene Tssui photographed outside his Berkeley office by Damien Maloney for PIN–UP 31, Fall Winter 2021/22.

-

2013 poster listing Eugene Tssui’s achievements as an amateur boxing champion. Image courtesy Eugene Tssui.

How can a building shout?

It can communicate in its form and materials: “I use recycled blue jeans for insulation. I am made of a material that has very little embedded energy and no functional toxicity. I am shaped by the wind, so I don’t have to worry about hurricanes or tornadoes. I am sheathed in a material that doesn’t ignite, doesn’t mold and mildew, and is waterproof. I will protect you from earthquakes, hurricanes, fires, and floods.”

Why do you think it’s difficult to innovate in architecture, environmentally, or otherwise?

Architecture is a tradition. People think that it should look to the past. Architecture is the last field of innovation. We’ve demanded innovation of everything else: phones, computers, cars, planes, boats... But the most innovative architecture? No. It is 150 years behind its time. We are still creating buildings the same way we did in the 1860s. Many of us are imprisoned by resale value and prefer to live in the past.

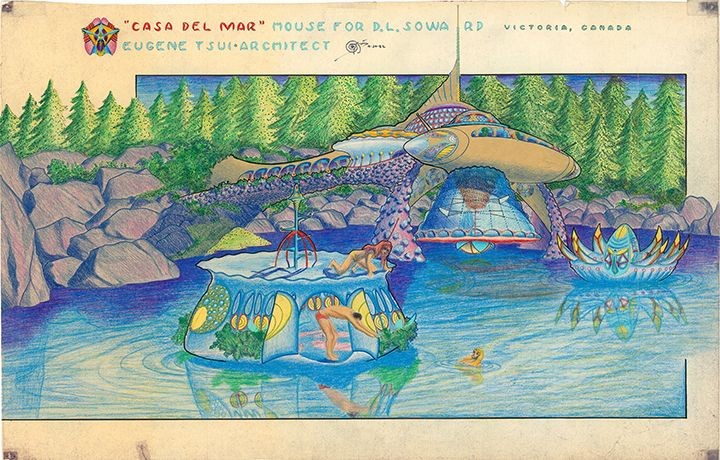

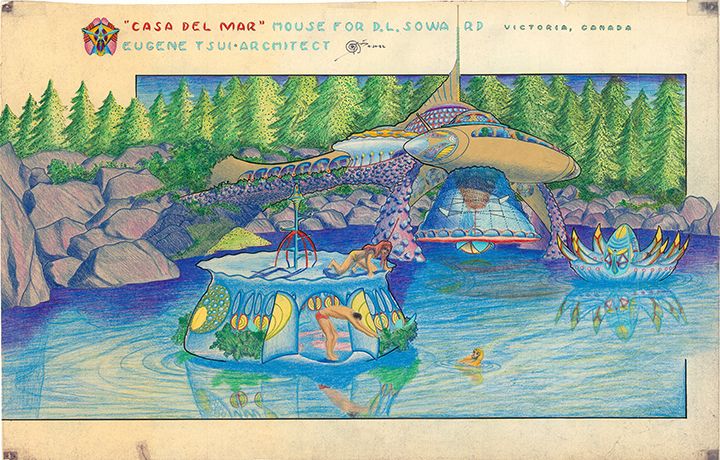

For Tssui, the home is both a launching point to the world and a sanctuary from it, as well as a place that expresses a “personal universe.” Casa del Mar (above) is a proposal from the early 1980s for an amphibious Canadian family abode that makes a minimal impact on the landscape.

Before finding solutions, how do you define the problems?

I ask fundamental questions, and I keep asking them. It begins with compassion and empathy, and doesn’t end there. Finding ways to end pain and suffering, whether emotional or psychological. The pain of alienation, or the pain of knowing that we are poisoning our air, our water, our soil, and the cruel, brutal, painful killing of animals for unnecessary consumption, the pain of deforestation, and much more. I am trying to do something to end that suffering. That is all a part of architecture. It is a dialogue rarely addressed.

Is that how your project for a floating bridge across the Strait of Gibraltar first came to mind?

That came as a result of reading about people trying to come up with a solution to create a bridge across the Strait of Gibraltar for decades. And I thought about it for a while, and I said, “I have the solution.” It has to be in tension, like a spiderweb. It would float in the strait like a floating hose — a tube in the channel. I just pictured it in my mind, instantly.

Eugene Tssui photographed by Damien Maloney for PIN–UP 31, Fall Winter 2021/22.

READ THE FULL INTERVIEW IN PIN–UP 31.

Eugene Tssui in the print edition of PIN–UP 31, Fall Winter 2021/22. Art Direction by Office Ben Ganz.

READ THE FULL INTERVIEW IN PIN–UP 31.

Interview by Nolan Boomer

All portraits by Damien Maloney

Nolan Boomer studied English at Oberlin College and architectural history at the University of California, Berkeley. They are one of the editors of the architecture magazine Take Shape.