INTERVIEW: Artist David Hartt Transforms A Frank Lloyd Wright Synagogue

Montreal-born, Philadelphia-based artist David Hartt has distinguished himself by his ability to work across media and scales, weaving together complex references in heavily-researched projects. Frequently his work grapples with how we experience architecture, the present encounter interacting with history and legacy — such as in his 2014 film Stray Light, where he created a video portrait of Chicago’s legendary Johnson Publishing Company headquarters. This September, Hartt opened an exhibition at another significant architectural site: Beth Sholom Synagogue in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, the only synagogue designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. With the help of Glass House curator Cole Akers, Hartt created connections through time and space in the 1959 building, with tropical plants, videos documenting Haiti and Louisiana, and a score by 19th-century New Orleans composer Louis Moreau Gottschalk, of both Jewish and Caribbean heritage, reinterpreted and performed live by Ethiopian pianist Girma Yifrashewa. The title of Hartt’s installation, The Histories (Le Mancenillier) references historian Herodotus’s ancient magnum opus and a tropical tree that produces the sweet yet poisonous fruit after which Gottschalk’s score is named. PIN–UP spoke with the artist about his work’s engagement with communal histories and the challenges of designing an installation in an active place of worship.

Exterior of the Beth Sholom Synagogue. Photography by Darren Bradley.

You’ve described this work as site specific — and it’s in quite a site. How do you work with a building with such a strong architectural presence and such major symbolic significance?

Dealing with the legacy of Frank Lloyd Wright and with the context of a synagogue, an active place of worship, could have been very daunting. So I looked at the history of the congregation for clues of ways that I might approach the project, and was quickly struck by the narrative of this being the second home of the congregation. Their original home was on Broad Street in Philadelphia’s Logan neighborhood, and due to the suburbanization that was happening at that point in time in the United States, the congregants had moved north to Elkins Park, leaving the former synagogue behind and commissioning Wright to construct a new one.

How do these things from outside the site — orchids and other tropical plants, videos from Haiti and Louisiana — fit in?

I was interested in this idea of movement of people, of culture. I found out that the original building on Broad Street is now home to a black evangelical congregation, which allowed me to weave in a parallel cultural narrative. That was the key that I was looking for, so I could begin to look wider than the specificity of the building while still remaining true to and honoring the narrative that was present. The installation in the synagogue is a departure from what was there, but that doesn't mean that it's absolutely foreign or alien or incompatible.

-

David Hartt, The Histories (Le Mancenillier) (2019): video still.

-

David Hartt, The Histories (Le Mancenillier) (2019): video still.

-

David Hartt, The Histories (Le Mancenillier) (2019): video still.

Formally, I was very much struck by your use of materiality. There’s the introduction of live tropical plants where there once were plastic plants. There are the videos on large monitors that acknowledge the screen by flashing Xs across them intermittently, a nod to the experimental filmmaker Michael Snow. There are digital images turned into large-scale tapestries. And there’s, of course, the music throughout. How were you thinking through materiality and immateriality when conceiving The Histories?

I think it has a lot to do with the way I see different mediums performing. The videos have as much to do with the image as they do with the scale and orientation of the monitors. It’s a way of invoking these other places and bringing them forward. I see the monitors as portals — they allow one to oscillate between the physical environment of the synagogue and the virtual environment beyond the frame of either Haiti or New Orleans. I'm trying to merge those spaces.

The tapestries are dealing with a number of issues, but primarily I was really thinking through Wright and his ideas of “total design.” I didn’t want The Histories to just be decoration; I wanted it to be able to be assertive as another architectural aspect of the space. So it needed to function at a certain scale, and it needed to be integrated and have a materiality that was sympathetic with the materials of the building itself. That's not to say that these tapestries are unique to just this building, but that they’re my response to the total design that Wright advocated.

This brings up, again, the issue of this being an active site. How did you work with the fact that people regularly use the synagogue as not only an artistic site, but as a site of worship and gathering?

I didn’t want to foreground the work to the point where it actually begins to get in the way of the functional aspects of the space. The curator, Cole Akers, and I did an inventory of how the space was used, asking what were the most active zones? What were the hours of operation? What were the things that just couldn't be impeded? Once we had an understanding of that, we began to understand that certain areas didn’t necessarily need to be left alone, exactly, but that we had to prioritize their function. Because of that, we realized that there was all of this other space that we could have a more active engagement with.

We designed a lot of the interventions around those non-contentious spaces, and then we started to realize that other parts of the space were underperforming, or had their own functional issues. The original artificial plants in their decorative function seemed like they were, to speak politely, underperforming. The roof was leaking, and the congregation had placed buckets and kiddie pools throughout the main sanctuary to address the volume of water coming down, and that also became something that we had to contend with.

That guided two interventions. Our response of removing the artificial plants and putting live plants that were native to the Caribbean in their place was a way of trying to use a part of a building that was underperforming and make it perform in a different way. It also gave us the excuse to be very expressive — like the pink grow lights. Those aren't Wright’s design, those are things that we added based on wanting to include tropical plants in subterranean spaces. But they don't change the character of the building, they express a new set of possibilities within the space. It's the same thing with the orchids; they are fulfilling the function that the buckets and kiddie pools did previously, it's just that they're doing it in a more exuberant way.

-

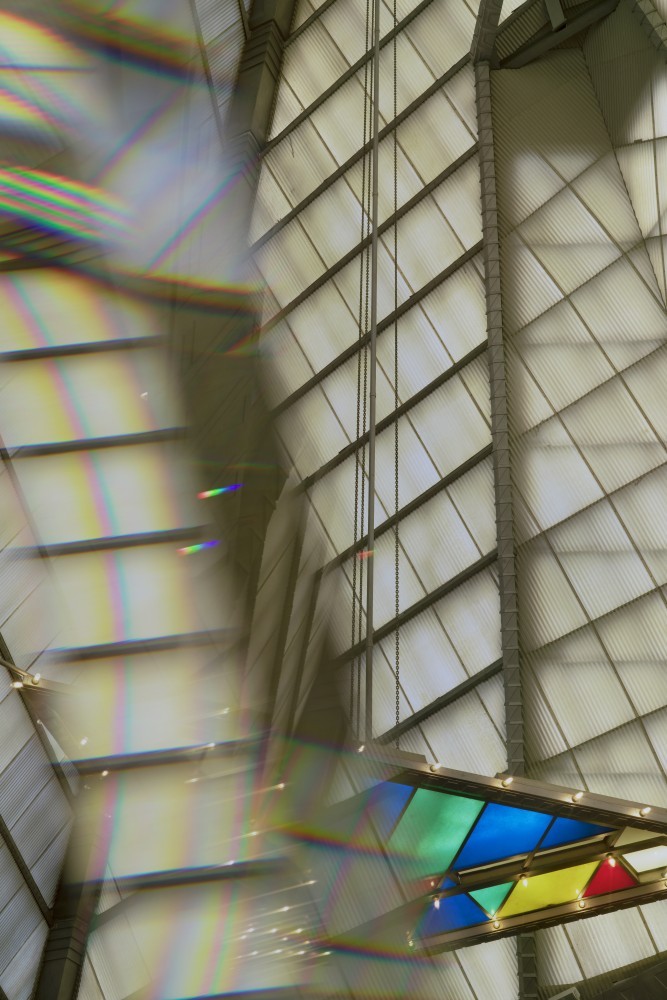

Installation view of David Hartt's The Histories (Le Mancenillier) (2019) at Beth Sholom Synagogue. Photography by Michael Vahrenwald.

-

Installation view of David Hartt's The Histories (Le Mancenillier) (2019) at Beth Sholom Synagogue. Photography by Michael Vahrenwald.

-

Installation view of David Hartt's The Histories (Le Mancenillier) (2019) at Beth Sholom Synagogue. Photography by Michael Vahrenwald.

This being a place of worship and a space for community, the issue of use is not just one of circulation or function in a direct sense, but also function in an affective and spiritual sense. Did this influence how you approached the project?

I don't know if there's necessarily a difference in terms of programmatic needs. The function of the building is to allow for a group or a community to gather and discuss and worship. Those are the programmatic priorities of the space. I’m looking at the building as a container, and the container itself is generous enough to hold a variety of beliefs simultaneously. This goes back to this point about two different spaces, two different communities being held together simultaneously within the space, whether it's Haiti and New Orleans in conjunction with this Wright building in Elkins Park, or black evangelical and largely white Jewish congregations occupying the same sites throughout history. I'm interested in a generous concept of community that the space is capable of embracing.

Text by Drew Zeiba.

Photography by Darren Bradley and Michael Vahrenwald.