HOW WE LIVE TOMORROW: A POSSIBLE ANTHOLOGY IN FIVE CHAPTERS

Since the beginning of mankind, humans have imagined what the future would look like. What kind of lives will we lead? What kind of transportation will we use? What will our dwellings look like? Our homes, our furniture, the objects we use and surround ourselves with? Ever since the industrial revolution, technology has played an important role in how scenarios for the future, are imagined, both enthusiastically embracing technological process as well as staunchly rejecting it. And yet most future fantasies imagined by humans, whether utopian or dystopian in nature, never quite happened as they were imagined. Or maybe they did, and we are already living in the midst of them without even noticing? The modern information age makes anything seem possible, and yet nothing is quite what it seems. Here architect Martti Kalliala speculates on a number of scenarios of what might or might never happen. Or do they already exist?

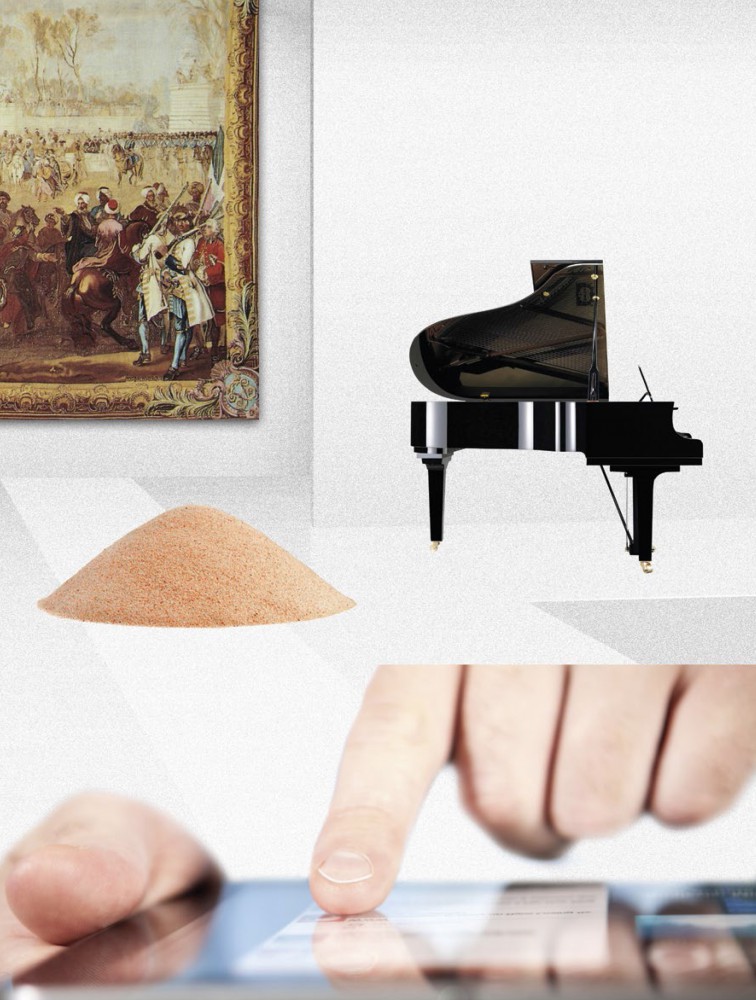

WHEN PINTEREST BECOMES FORM

Martti Kalliala, When Pinterest Becomes Form, 2017; digital collage, 21.5 x 30cm

A tabula rasa, a blank canvas, a carte blanche; whatever material the home was originally constructed of, its interior surfaces have now been washed out into a pure, matte white. Except for the glass of the windows no nook or cranny has escaped a brush soaked in perfect RAL 9010 latex paint. The home has become a white cube, where “interior design” and “furnishing” have been replaced by “curation.” These domestic spaces are occupied by sparse arrangements and assemblages of affective objects, to be reconfigured or completely redone in a cycle of four to twelve weeks. Not primarily to be lived in, or to be used, but to be mediated, contemplated, and consumed as images. Liberated from a pledge to utility — to be useful — these spaces surpass the beauty of any abode of today: In the corner a Shanzhai version of a Grcic chaise longue (its label tab says Aquascutum), on the wall a curved 64-inch screen playing a video loop of a greenish fire that surprisingly also emits heat; in the middle of the room a small, Andrea Branzi-esque, softly textured sculpture that doubles as a cat tree. A Turkish Angora cat in the exact color of the lounge chair sits on a window sill; next to the kitchen on a white plinth a composition of avocados, gracefully decayed apples, and fist-sized clumps of compressed crystalline e-waste sit on a 3D-printed kintsugi ceramic dish. A white grand piano, thirty pieces of the same chair arranged in an order verging on chaos, a stuffed coyote, and a 15th-century Gobelin: The insta(ll) shots look simply amazing.

This incessant circulation of objects wouldn’t be possible without the development of a vast supporting infrastructure. Indeed, the outskirts of the city have become cities for objects. Big box retail stores along ring roads are flanked by cloud storage facilities housing the furniture, books, art, household objects, ephemera, and sometimes plain junk, that was formerly stored inside homes. In fact, most things acquired from the big boxes are stored directly into the “cloud” without first passing through a home. As in data centers, packets are deposited and retrieved day and night as curator-decorator-inhabitants mix and match — “juxtapose” and “negotiate” — objects and meanings on their screens at home and simply file in their orders.

TOGETHER FOREVER

Martti Kalliala, Together Forever, 2017; digital collage, 21.5 x 30cm

Across the urban world, real estate prices keep rising, ultimately curbing the entry of generations Y and Z to the housing market once and for all. Occupants might own a share of their shared home—most likely not—but at its core the dwelling isn’t anymore considered property but a service. Occupants live with their #fam, phyle, thede, creche, polypool, smart contract family, FAOS (functional arrangement of strangers), or cloud community gone IRL. Correspondingly it is a widely held belief that the nuclear family and its associated single family home was nothing but a historical anomaly. Liberated from the possibility of ever owning one’s home, one is allowed to rethink the foundational concept: a safe space, welfare hotel, incubator, or a boarding house 2.0 catering to one’s chosen lifestyle and associated journey of self-development. Some co-living units offer slow food jams, CrossFit revivals, and Pickling 4 Preppers seminars while The Coming Insurrection reading groups gather in the common room, where they’ll find a military-grade Vitamix, a sofa for seven, and a gas stove in the shared kitchen. Other shared homes are structured around more austere, socially disciplined forms of life akin to what one might describe as a secular monastic order.

Individual rooms, cells, and pods differ greatly from house to house in size, shape, and design, but what they tend to have in common is an obsession with the bed — the locus and platform for work, rest, procreation, and education. From 11-layer futons to czar-sized Hästens in Yayoi Kusama patterns to artisanal weighted blankets with embroidered inspirational motifs, co-living service providers respond to the ever-changing needs and desires of a new class of connoisseurs of horizontal existence.

This bubble collectivity has a huge spillover: cities incrementally become archipelagos of micro-cities, some in the scale of individual buildings, others of whole districts, each exhibiting a particular model — architecture, economy, culture, and aesthetic — of how to live together. Soon enough these islands begin to mushroom: many upmarket homes are distributed transnationally across a number of cities which themselves begin to transform into sovereign “zones.” Re-coded forms of urban customer-citizenship arise; a distributed e-residency, urban elite members club, recognized across a variety of globally distributed federations, unions, and alliances of “smart” city-states enclaves: Muji X eStonia, Swissport, Candy&Gandhi, Alphabet Cities.

DISRUPTION BEGINS AT HOME

Martti Kalliala, Disruption Begins at Home, 2017; digital collage, 21.5 x 30cm

On the 52nd floor of 420 Park Avenue in the exclusively solar-powered Gigacity Midtown N-clave, a home lies unoccupied. Swarms of Roomba vacuums tirelessly keep all surfaces clean while autonomous repair bots wage a slow battle against entropy. No one has ever lived in this dwelling and likely no one ever will. In fact its interior air is completely devoid of oxygen and consists solely of nitrous oxide to keep the furniture and collections of early 21st-century art (including many precarious installations) intact. The only purpose of this home — and the other 98 directly above and below it — is to function as a repository of value. Some feel a bit uneasy about these empty shells of buildings and their artificially intelligent ghost inhabitants. Yet the same alien others have become widespread flatmates as the “smartness” of one’s home has become an expected, default feature. Every device, surface, and object speaks to each other in a silent machine language coordinating their efforts to manage one’s home. The popular KonMari™ AI smart home module has only a single goal: to unclutter. Its blind insistence on this task tends to make inhabitants anxious as sometimes it seems it would do whatever it takes to reach this goal, including disposing of its owners. But then again, never in the history of mankind have human dwellings been as spotlessly clean and uncluttered as today. On the other side of the world another home of a much more modest stature lies unoccupied; then suddenly a four person family moves in only to be replaced by a start-up nine days later, to be replaced after three months by 40 tonnes of raw aluminum that will stay there for the following three years. As it happens, under certain circumstances, the concept of “home” does not refer to any sort of permanent residence but one out of multiple uses attributable to any built space. Space itself has become a liquid asset, its functions, inhabitants, and material flows auctioned, traded, and speculated on the AIRBNX marketplace, thus most new construction adheres to the principles of infinite flexibility. A “home” is only one of the possible profit generating concoctions that can flow through space.

AGELESS BUT NOT YOUNG

Martti Kalliala, Ageless But Not Young, 2017; digital collage, 21.5 x 30cm

Both rapid advances in biotechnology and the widespread adoption of the design principles laid out by the Reversible Destiny Foundation in their Bioscleave House (a house built as a machine for living forever) have led to the emergence of almost-non-senescent inhabitants that occupy their homes seemingly forever — at least from the perspective of those who choose to live as organic non-GMO humans. Those luckier ones who in the early 2000s rented apartments in coveted turn-of-the-19th-century buildings might be enjoying the perks of rent control well into their 130s. These homes — affectionately nicknamed mausoleums — have been retrofitted with uneven floors (to keep one alert) and a variety of vertical and horizontal bars, handles, grips, ropes, slings, and rings (to stimulate movement) that have seemingly replaced anything traditionally understood as “furnishing.” Both aesthetically and functionally they are a curious mix of calisthenic park, BDSM playground, and the activity interiors built for primates exhibited in zoos, where limber ageless-but-not-young bodies swing from room to room. The 3-D landscape of the house, in combination with the body’s friction, produces an aesthetics of resistance to corporeal complacency…

KINVOLK

Martti Kalliala, Kinvolk, 2017; digital collage, 21.5 x 30cm

The widespread longing for an #exit — an escape to an outside or elsewhere — assumes a variety of forms. Those with the means surf the market and change homes and living situations on a whim, others move to tower blocks built into airports being jurisdictionally and psychologically forever “in transit.” Others decide to leave altogether.

Outside cities, in the woods of the Pacific Northwest, Scandinavia, Western China, and the Japanese Alps live a people known as kinvolk. A generation fed on aspirational imagery pertaining to authenticity, community, and “real experiences,” where everything is craft and elaborate organic breakfasts represent an escape from their precarious jobs in the creative industries and endless austerity measures, have decided to “go native,” and leave the mid-21st-century behind. Deep in the insta-worthy scenery of the forest, Le Corbusier’s Cabanon, Ted Kaczynski’s hut, and Thoreau’s Walden are authentically replicated and modded to allow for other manners of inhabitation than that of the single male bachelor. Furniture reminiscent of the Shaker and Autoprogettazione traditions, driftwood assemblages, dried flowers, and the occasional flotsam of industrial civilization adorn the sensually austere interiors of these arcadian huts, creating the perfect post-information-industrial idyll.

Others are bothered by the kinvolk abandoning the future as it was supposed to be like, condemning them as neo-Luddites or hopeless romantics for an idealized past. But the kinvolk know that time and progress don’t move forward as a unilinear arrow. Time — and with it culture — is a spiral: everything that once was will return, but in different form. The kinvolk know we will live tomorrow as we lived in the past — only differently.

--

Martti Kalliala is the co-founder of Nemesis, a think tank and consultancy based between Berlin NYC and Helsinki, and a member of the internationally performing “xperienz design” group Amnesia Scanner.

Text and artwork by Martti Kalliala.

All original text taken from the book This Will Be The Place (Rizzoli, 2017), a monograph edited by Felix Burrichter celebrating 90 years of the design company Cassina.