FREE ROAMING: A Review of the 2018 Venice Biennale

In an interview leading up to the 16th edition of the Venice Architecture Biennale, the curators, Shelley McNamara and Yvonne Farrell, of Grafton Architects, admitted that the theme they devised, Freespace, was difficult to define. Space that’s free? Free of what? Free for whom? To help guide participants, they penned a manifesto as sprawling as the theme was nebulous, but touched on a couple of interpretations: the political, the environmental, the social, and the humanitarian, among others. Even if it reads as a bit cloying, its optimism is welcome during a time of global unease and represents an encouraging salvo for participants to explore the generosity implied by the word “free” and how the built environment can be shaped within this ethic. The serene installation of the Corderie section of the Arsenale embodied this liberality. Work was installed behind its colonnades, leaving room for circulation down the central walk of this former warehouse building offering the ability to both observe installations and regard the space at the same time. Charles Eames famously proclaimed that an open brief from a client is the worst kind of brief. Designers work better with constraints. Such a level of freedom for Biennale participants meant that, in a way, they wrote, and answered, their own brief. Reciprocity of this magnitude runs the risk of designers presenting work that only speaks to itself, and at times that was the case, but the most engaging Biennale installations and national pavilions displayed the process of discerning freespace’s contours — not just its endgame as a utopian ideal. Freespace, then, is a negotiation. If Venice is any evidence, the social conception of freespace is something that can be gained and lost. Sebastiano Ziani, a 12th century Doge of the Venetian republic, revolutionized the dogeship by encouraging more participation from citizens through the construction of an ancient forum-inspired platea, or square, in the area now known as San Marco square and an adjoining communal palace. By the 13th century, however, the palace was transformed by commercial interests who had taken control over the republic and who had little desire to hear the public’s wishes. It’s heartening, then, some 900 years later, to see that, on a global scale architects and designers can separately come to the table with common ideas of freespace. Several of them follow below.

Inside the German pavilion curated by Graft architects. Photo by Italo Rondinella.

FREE REIGN

Does freespace have borders? Germany’s pavilion installation, Unbuilding Walls (curated by Graft) looks at how the area formerly known as the “death strip,” between the two partitions that constituted the Berlin Wall, have been used since its fall after nearly 30 years. Descriptions of projects and cultural activations — from raves to bike paths — are presented in text and photographs on upright drywall slabs abstracted to look like remaining pieces of the wall, scattered throughout the pavilion. Together, they form what looks to be a black, formidable barrier when seen frontally from the entry to the pavilion. Architect Teddy Cruz delves into a similar investigation of liminal border space as one of the designers representing the United States pavilion. He exhibits a map of “MEXUS,” a hypothetical region along the U.S.-Mexico border redrawn to encompass the natural and economic networks that currently exist and are otherwise delimited by the less permeable border that currently exists between the two nations. His is one of eight installations that examined the Dimensions of Citizenship. Here, too, Keller Easterling together with MANY use iPhone displays to show a hypothetical narrative of migrants and unsettled populations connecting with people sharing resources and services in a networked digital platform that omits the role of the welfare state altogether. Over in the Corderie, Skälsö Arkitekter presents Bungenäs, a project located on an island of the same name in the Baltic Sea. Here, the architects were asked to design the island’s master plan incorporating its former military bunkers. They’ve dismantled and repurposed these concrete buildings into residences, commercial buildings, and public seating. At the Biennale, eight hulking concrete blocks from Bungenäs serve as plinths to exhibit the models and drawings of the island’s architecture — a further liberating transformation of a formerly oppressive material.

The installation Tread Lightly, A Linear Festival Along the Transcaucasian Trail by Gumuchdjian Architects. Photo by Francesco Galli.

ROAM FREE

In contrast to the global turn towards urbanization, several installations and pavilions examine rural areas as freespace — sites of depopulation, architectural experimentation, and infrastructural development. China’s pavilion, Building a Future Countryside, included an inventory of new architectural works in its hinterlands. Photographic documentation of buildings: from residential and cultural to agricultural show an impressive range of development taking place in rural China, but one wonders if architecture could have an exploitative role considering the harmful environmental side effects of the country’s rapid urbanization. For Archipelago Italia, the Italian pavilion wipes the metropolitan areas from its map and focus on its countryside as an “archipelago” of eight regions, articulated in itineraries that highlight their new and vernacular architecture. Explanatory texts contextualize these buildings in each region’s religious, social, and industrial histories. A second room proposes five speculative projects for Italy’s countryside rendered in exquisite models on a giant, amoeba-like wood table whose piney fragrance evokes a forest. Suspiciously absent, however, is any mention of how NGOs in Italy are working to settle migrant populations in rural towns and how design could accommodate the needs of immigrant Italians. In the Corderie, Gumuchdjian Architects presents Tread Lightly, A Linear Festival Along the Transcaucasian Trail, a ten-year eco-tourism project that seeks to build a 750km trail in Armenia’s backlands to connect its towns and countryside using the help of volunteers and townspeople along the way. The extended 10-year timeline is purposeful: it allows for the patience and slowness to develop infrastructure sensitive to both human passersby without sacrificing or harming the freespace of the natural environment.

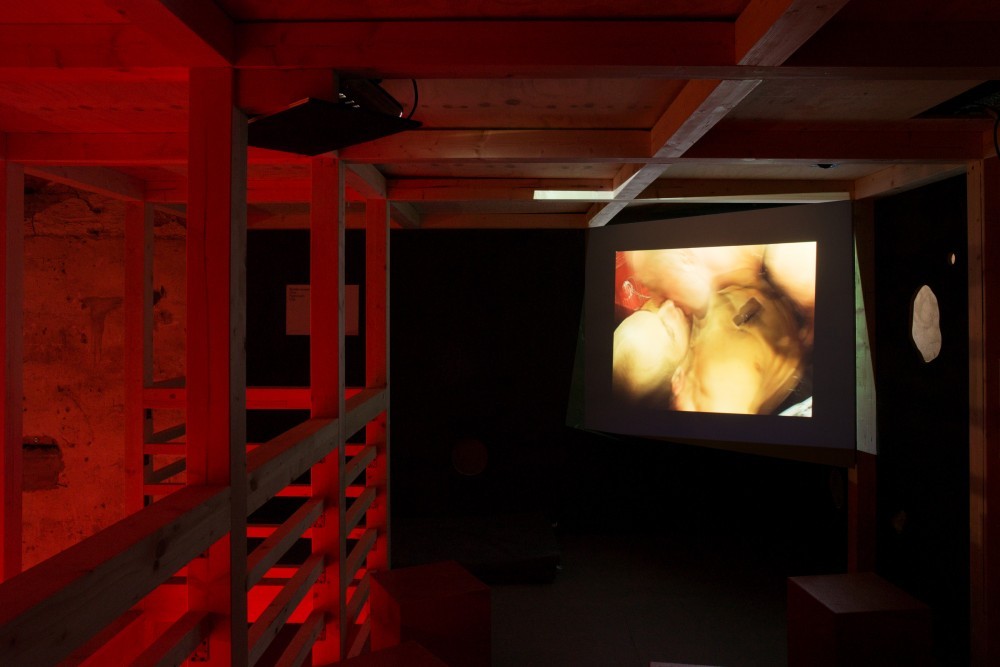

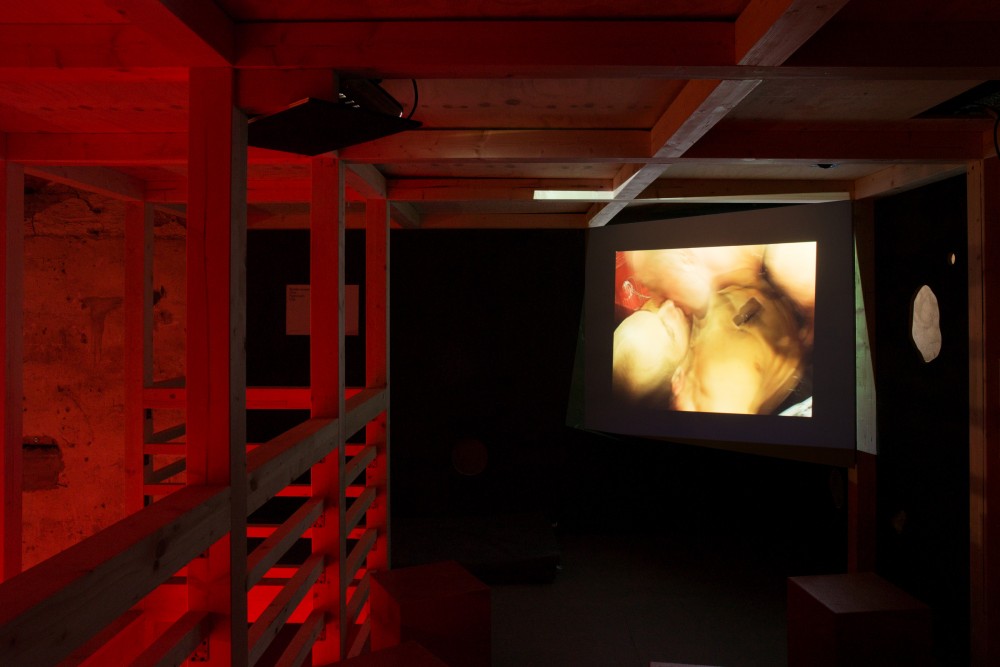

Installation view of the Cruising Pavilion. Photo by Louis De Belle.

FREE LOVE

Sex is nowhere to be found in the freespace manifesto. In response, the four curators of Cruising Pavilion — Pierre-Alexandre Mateos, Rasmus Myrup, Octave Perrault, and Charles Teyssou — brought together 22 practitioners in a double-height industrial space in Giudecca to highlight architecture’s erotic potential. Cruising, or searching in public for sexual encounters, is one of the freest of spaces — at least when considering inhibition, but it’s a space contested by the rest of society, which means that those who cruise have to find creative ways to thrive secretly in public. The curators choose works that explore extant or speculative architecture intended for sexual encounter, document cruising’s history, and point to its digital turn. Works by the likes of Ian Wooldridge, Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Andreas Angelidakis, S H U I, Andrés Jaque, Monica Bonvincini, Pol Esteve & Marc Navarro, among others are installed in an environment reminiscent of the interiors of “dark room” club and bar spaces that accommodate cruising and public sex.

Amateur Architecture Studio’s How to ‘Legalize’ Spontaneously-Built Illegal Structures in the City By Means of Design at the Central Pavilion.

FREE YOUR BODY

Architecture, when experienced at varying scales, can produce different haptic responses, making one aware of the freedom and constraints of their body in space. The Central Pavilion’s installation produces and comments on the impact of this scalar range while also showing the interwoven influences of history on architecture. The “Close Encounters” section invites contemporary architects to reimagine historic works in large-scale installations scattered throughout the parlor. Carr Cotter & Naessens Architects’ interpretation of August Perret’s Salle Cortot (1929) theater is represented by a wood crate with an opening barely big enough for one’s head. Classical music trickles out and draws viewers to look into a model of the theater with a little wooden piano, its frame brandished with quotes from Perret including: “I will make you a room which will sing like a violin.” It forms a strange kinship with a much more outsize installation in the room next door. Amateur Architecture Studio’s How to ‘Legalize’ Spontaneously-Built Illegal Structures in the City By Means of Design takes over an entire room with a walk-through scaffold structure that exhibits photographic documentation of their work in Hangzhou to preserve and fortify vernacular “urban villages” in the face of the state’s efforts to demolish them and build soaring residential buildings. Here, both Perret by way of Carr Cotter & Naessens along with Amateur Architecture Studio both see potential for architecture to facilitate collective and cultural exchange when realized on a smaller scale.

The interior of the Austrian pavilion. Photo by Martin Mischkulnig.

Austria’s pavilion, Thoughts Form Matter invites viewers to climb a labyrinthine scaffold that snakes up and around the vaults of Josef Hoffman’s original 1934 building. Designed by Henke Schreieck, the installation bisects the building’s interior colonnade and allows visitors to confront architectural elements that they would otherwise not observe close up. A pleated paper curtain falls the ceiling to the floor, interrupting the scaffold’s climb and cleverly animates the cross-breeze moving through the pavilion’s giant doorways, making tangible more atmospheric conditions. Finally, in the Swiss pavilion, which also won the Golden Lion, Svizzera 240: House Tour (curated by Alessandro Bosshard, Li Tavor, Matthew van der Ploeg, and Ani Vihervaara) creates a sequence of rooms with generic surfaces and treatments that seem common to a middle class model home or apartment. The catch is that each room varies wildly in scale, but repeats the same elements from the room previous: only much bigger or smaller. Visitors have to duck through doorways in one room or reach above their head to maneuver a door handle in the other. Baseboard moldings are at times minuscule, other times, they rise midway up your calf, demonstrating that the spaces that one may think are free, are in fact highly controlled by standard design elements we take for granted.

Text by Jordan Hruska.