Interview: The Brave New World of Autistic ARCHITECTURAL Artist William Scott

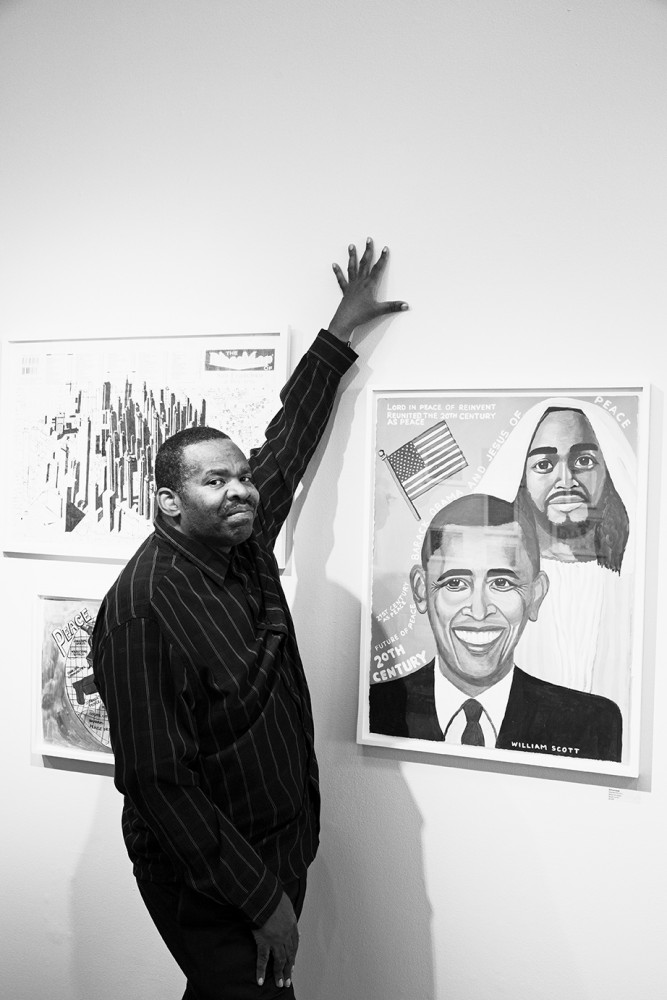

The artist William Scott photographed by Daniel Trese for PIN–UP.

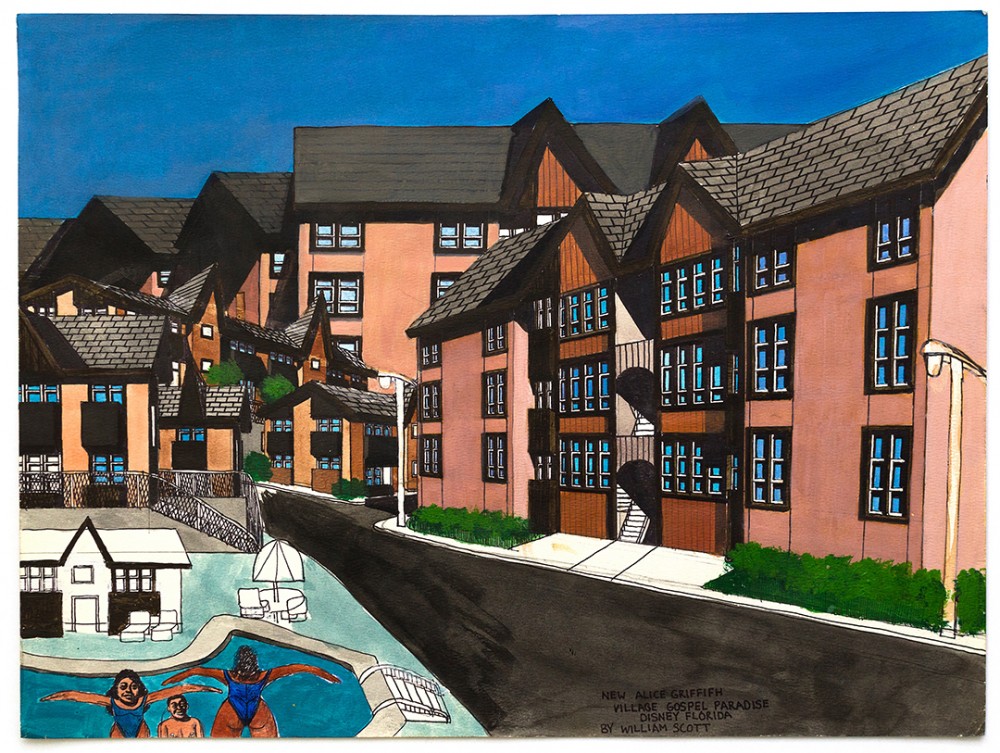

William Scott’s unique body of work is influenced by a dual condition: he was born schizophrenic and is also on the autistic spectrum. Words fail him. His language limits don’t allow him to share the complex scope of his thoughts verbally. For 54-year-old Scott, painting is as necessary as speech. Since he began to draw as a child, Scott has been obsessively redesigning the two cities he loves: San Francisco and his hometown of Oakland, just across the bay. The thousands of paintings and drawings he’s produced over his lifetime all share the same mission, which is to improve residents’ lives so that they are happier and more peaceful. His work offers a wide range of solutions, from specific redesigns of buildings that form part of Scott’s personal history — the Fox Plaza apartment tower, San Francisco General Hospital — to entirely new structures — his Martin Luther King Tower — or new government agencies such as the Center for Opportunity or the Skyline Friendly Organization, both intended to spread happiness and understanding. In an effort to create places of maximum enjoyment, Scott also creates geographic mash-ups that combine the best of San Francisco with elements from other places like the Bahamas, Hollywood, or Disneyland (which he dubs Disneywood). In fact, Scott’s work is so centered on building a better city that when you ask him how he should be defined he prefers the title architect over artist. PIN–UP met Scott in Oakland on what was a landmark day in his career: the launch of his first monograph William Scott: Painting Utopia, published by Creative Growth Art Center, a non-profit that since 1972 has been providing studio space, materials, and guidance for men and women with physical, mental, and developmental disabilities. Scott’s studio has been here since he was introduced to the organization in 1992, and his book signing took place in the center’s gallery. Thanks to Creative Growth’s encouragement over the years, Scott has emerged as one of San Francisco’s most prominent artists whose work is collected by New York’s MoMA, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and The Studio Museum in Harlem. PIN–UP was honored to conduct Scott’s first ever interview and to meet a radiantly positive man who is every bit as happy, funny, and generous as the world depicted in his paintings.

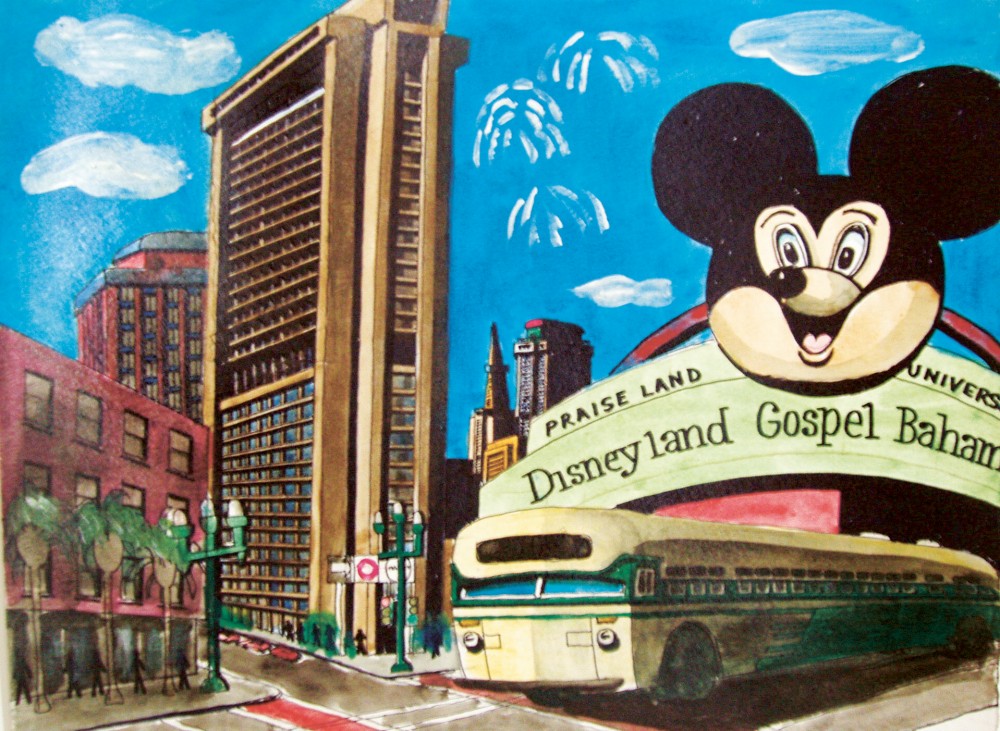

Wiliam Scott, Untitled (undated); Acrylic on paper, 15 x 19.875 in.

Michael Bullock: William, I admire your architectural drawings very much.

William Scott: Thank you! Share them with Tiffany Bohee. She works at the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency.

Why do you want her to see them?

WS: Because I’m an architect. (He points to a painting in his book.) That’s my design to rebuild the Martin Luther King Towers. It’s a public-housing project for white people, Indian people, Asians, and black folk. Geneva Towers are gone now. (Geneva Towers were a troubled 1967 housing development in San Francisco that was demolished in 1998.) I’ll design the new MLK tower to take the place of Geneva Towers in the future in 2020. That’s reality. Tiffany Bohee in the Redevelopment Agency should see that.

What kind of changes do you make to these apartment buildings?

WS: New balconies, new bathrooms, new bedrooms.

Why new balconies?

WS: So people can see the view… They don’t exist now. That’s going to exist in 2020. I will make a better tower for people to use. I want to design those towers for everybody to live together in a good high rise.

Can you describe a perfect living environment?

WS: Living in a peaceful world.

How is that expressed in architecture?

WS: Private balconies to make people better. Space for reflection. To give them more peace. Yeah. Help make good people.

-

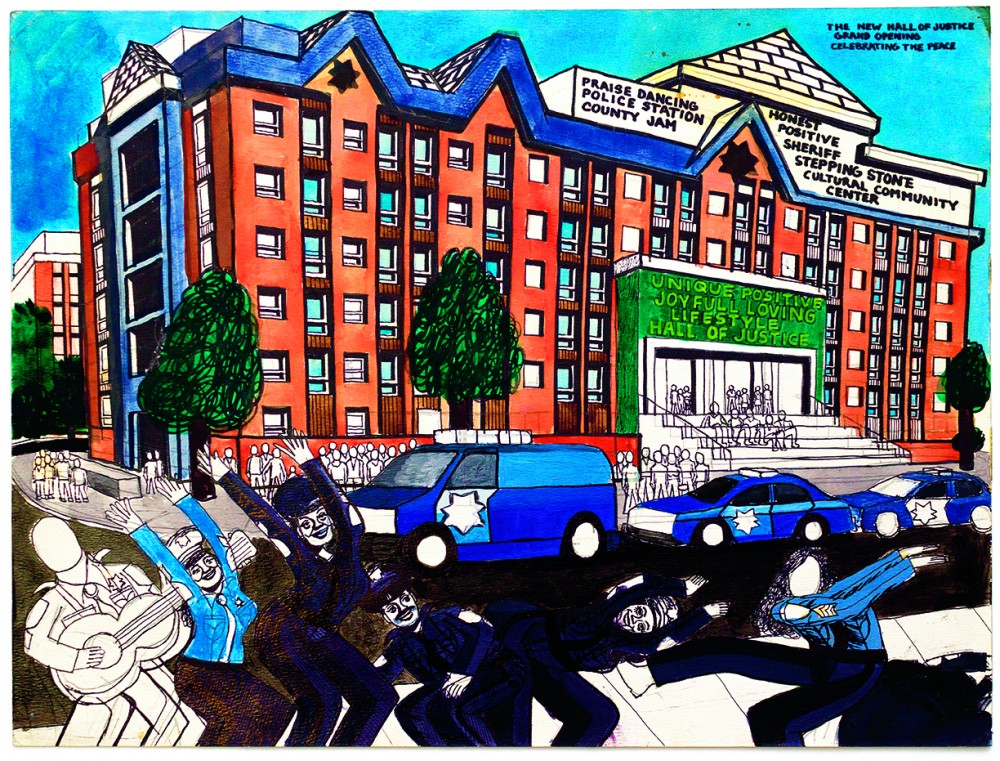

William Scott, Untitled (2007); Acrylic on paper. 18 x 24 in.

-

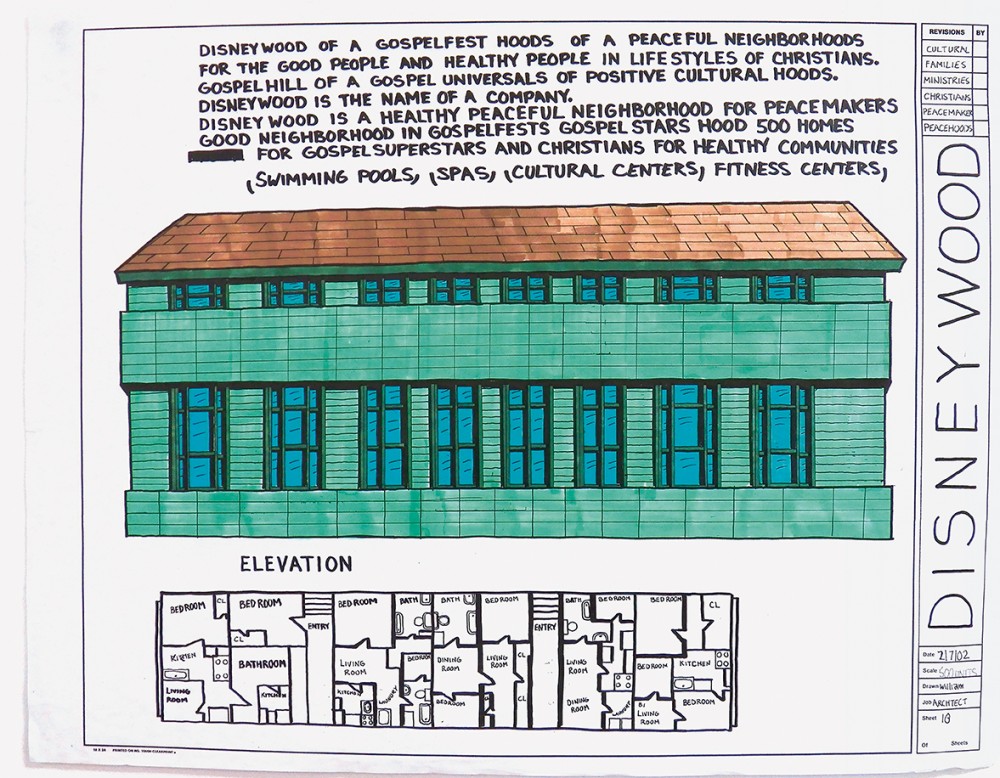

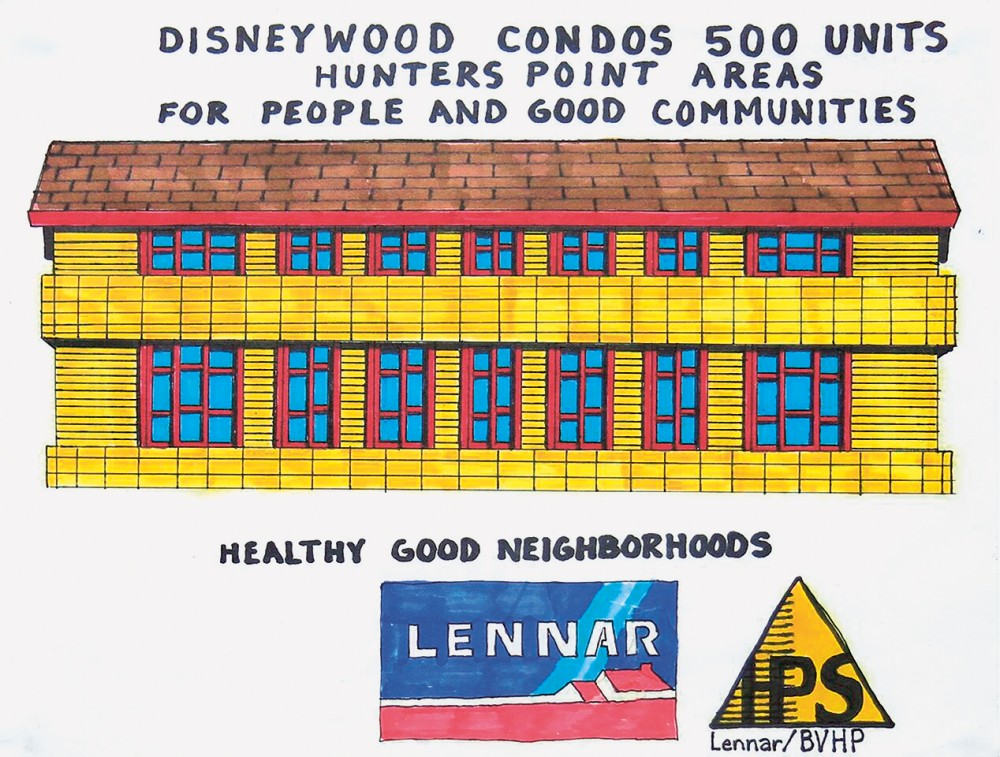

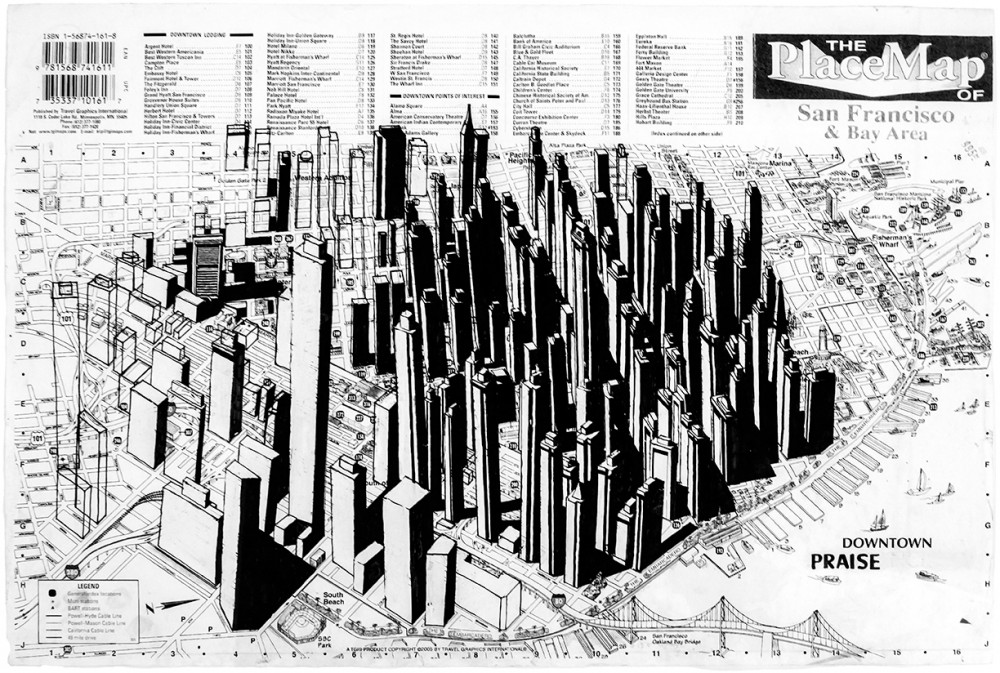

William Scott, Untitled (undated); Ink on paper. 8.5 x 11 in.

-

William Scott, Untitled (2007); Acrylic and marker on paper. 18 x 24 in.

Tell me about the drawing with the courthouse and the police station?

WS: I added dancing. I want to make it better. That’s Disneywood. This is going to be the future Hunters Point. Up on Hunters Point Hill. (Scott reads the text on the drawing aloud:) “Disneywood of a Gospelfest hood of a peaceful neighborhoods. Gospel Hill of a Gospel universals of positive cultural hoods. Disneywood is the name of a company. Disneywood is a healthy peaceful neighborhood for peacemakers. For Gospel superstars and Christians for healthy communities. Swimming pools, spas, cultural centers, fitness centers.”

What’s this building here?

WS: An Opportunity Center. Where we are going to talk about peacemaking. It will be built in the year 2070 because that’s a future plan.

In this drawing you combined the Bahamas, Hollywood, and San Francisco? Why the Bahamas?

WS: So people will live peacefully.

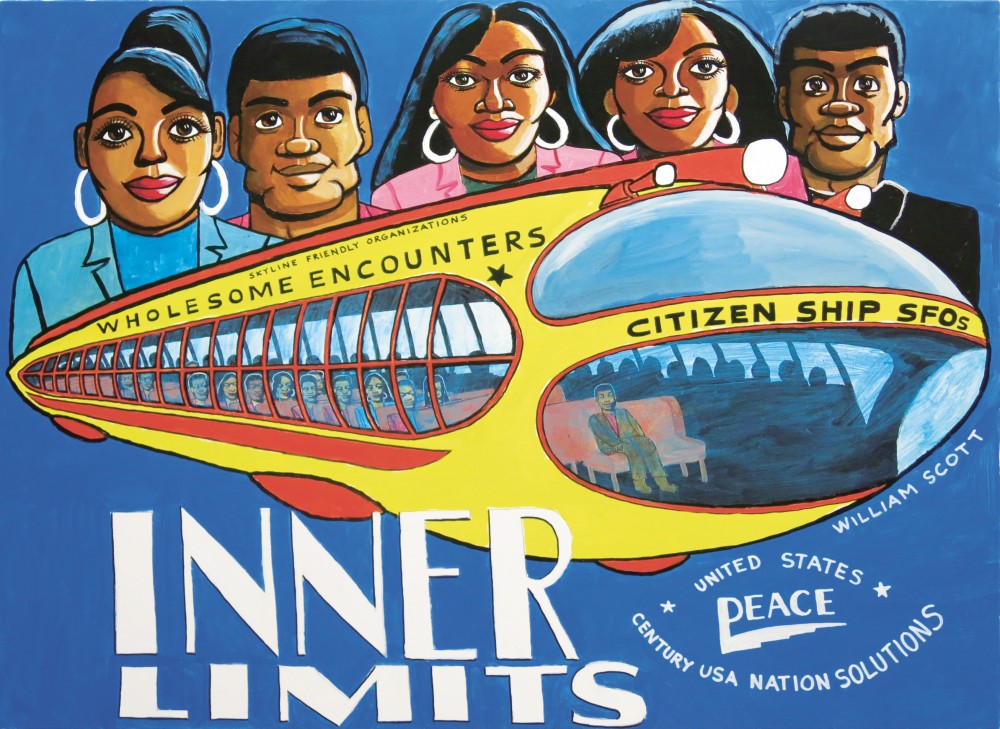

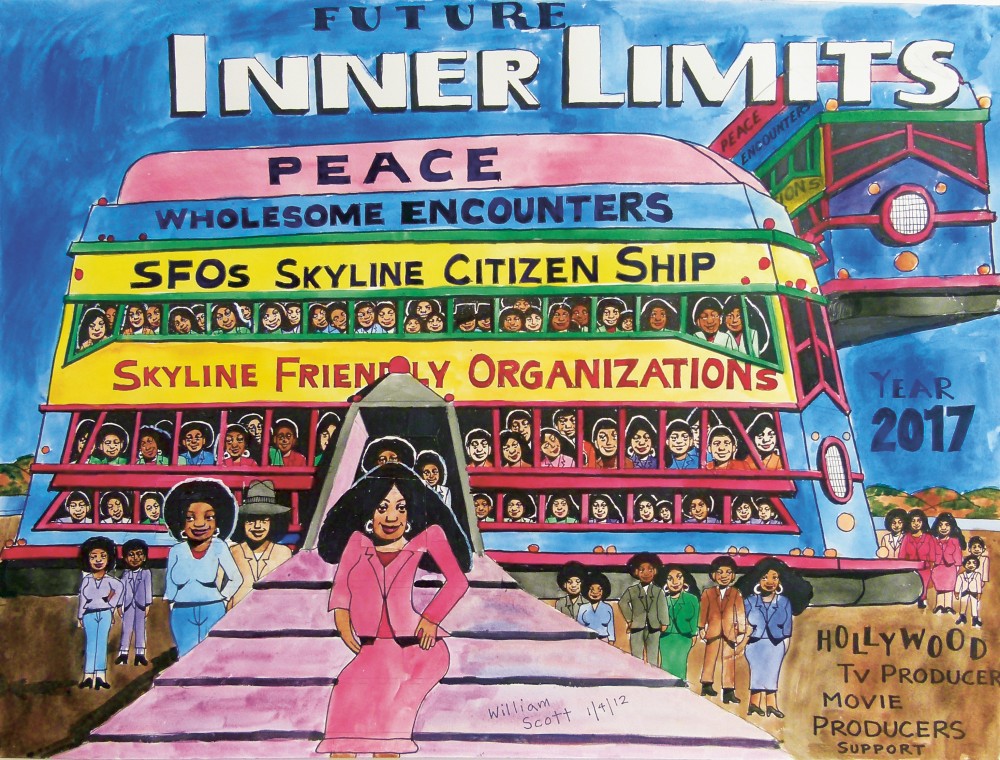

The slogan “Inner Limits” appears in so many of your paintings. What does it mean?

WS: Inner Limits is the name of the people in the Skyline spaceship. They bring people’s lives back from the dead. They bring people back as peace. So Martin Luther King is not going to be assassinated in 1968. He will be staying alive. MLK is going to be brought back to life on the Skyline. The 21st century will be coming back as peace because there was too much violence in the 20th century. There were a lot of assassinations in the 1960s. JFK was assassinated… It was a sniper from a warehouse. Do you remember?

William Scott photographed in his studio by Daniel Trese for PIN–UP.

When we look at your Inner Limits paintings, we see people coming out of the spaceship. Who are they?

WS: They are not imaginary, they are real people, people who are now alive. San Francisco will become original back in the 1960s. See the vintage buses? Those are my favorite because in 1972 my sister used to take me home to Harbor Road on that bus. See them in my book? The people at church will get this book.

How will the people at church react when they get your book?

WS: It makes me feel better because they can understand my good vision.

There’s so much positive energy and love in your work. What’s the goal when you sit down and draw your city?

WS: I want to be a peacemaker. I want it to be a better world.

That’s why you write letters to the mayor, so he can implement your ideas and improve your city?

WS: I wrote to Gavin Newsom because he is the mayor of the Redevelopment Agency. Tiffany Bohee works for him. Ed Lee was mayor after him. I put his name in a painting. He had a heart attack at the Safeway grocery store; he died at the San Francisco General Hospital in December.

Have you been to the San Francisco General Hospital?

WS: I used to go to the burn center. When I was 8 years old I put my T-shirt on the stove and it caught on fire. I was burning. My mom ran downstairs. She was naked. My body hurt real bad. I was screaming in the hospital. Here is a picture I made of it. It says, “The New San Francisco General Hospital in the future new developments of burning units architect and designer William Scott.” I remember that building from memory because it got torn down in 1976. It’s no longer there.

How do you start a drawing like that?

WS: I start to sketch. I use a ruler to make windows and details.

How did you learn to draw perspective so well?

WS: Because I’m the artist. Do you have Tiffany Bohee’s phone number? Can you call her?

I’m sorry I don’t know her. What’s the Social Relationship Friendship Society?

WS: That’s the name of a community church that I made. Do you want to see my body? (He shows me a painting in his book of him bare-chested with a scar on his torso.) That’s the burn right here. I want the scar removed. I will be thankful to go to heaven first. I will be reborn Billy the Kid, a basketball player. Do you want to read that?

William Scott, Untitled (2011); Acrylic on paper. 30 x 22 in.

Sure. “Forever memories. Last life old life. Old. God’s plan. William. reborn. New life. New.” In that picture, we see you with your scar; then we see you “new” without the scar. This is a recurring painting. Is that what you would like to happen?

WS: Yes, because it makes my body new. When I repaint it, I don’t feel worried. I don’t get shocked. I let everything go.

If I read the artist statement that you wrote can you explain things for me?

WS: Yes.

“William Scott is the amazing artist for peace celebrating in 2017 to be hiring the SFOs wholesome encounters.” What were you celebrating in 2017?

WS: Bringing people’s lives back. Bringing up the memories, putting people’s brains inside my head, putting people inside their brains, putting memories inside their brains for peace making.

Peace is a major theme in all your paintings? Why do you connect so much with the concept of peace?

WS: No violence, no war. Peace is quiet.

You say you’ll be hiring the SFOs. What are they?

WS: The Skyline Friendly Organization. They’re nice people.

“Brings people’s lives back who lost their lives. Inner Limits is the name of the Skyline People who hires the peace on the planet to be taking the war off the planet no more bad people no more crimes. Scientists will be supported.”

WS: That’s right. Scientists will help build spaceships. We need them to create progress. So they can bring the people back to life.

Everyone comes back, even mean people?

WS: Everyone comes back as peaceful people.

-

William Scott, Untitled (2014); Acrylic on canvas. 30 x 44 in.

-

William Scott photographed by Daniel Trese for PIN–UP.

-

William Scott, Untitled (2012); Watercolor and marker on paper. 18 x 24 in.

Last night, Creative Growth hosted your book signing. Who did you see in the gallery?

WS: Jesus and Barack Obama. (He points to his painting of the two together.) That’s me and my mom with Jesus. (He points to a painting in his book.)

That’s how you two looked in the 1970s?

WS: Yeah. I had an afro… That’s in another life.

Your mom told me that one of the first drawings you made when you were about seven showed the Golden Gate Bridge and that you drew traffic going both ways. You were already very observant?

WS: Yes. I remember that drawing. I always drew naturally. It will make me become an artist.

How did you first come to Creative Growth?

WS: I used to draw in the Waden Branch Library in Hunters Point. I drew architecture in 1979. One of the librarians noticed my drawing and thought I should be an artist. She brought me to Creative Growth.

What was it like when you first found this place?

WS: It was real nice, this place. I feel good at Creative Growth. I’ve been here since 1992 because I learned how to draw. I have my own studio. I come here every day. I love this place.

Did you make big paintings before you came to Creative Growth?

WS: I painted Diana Ross because she’s a good singer. I went to a Diana Ross concert in 1985. It was great, she sang, “Reach out and touch somebody’s hand, make this world a better place if you can.”

That’s very much in line with your philosophy. Your art also shows us how the world can be a better place.

WS: That’s right.

William Scott, Untitled (2006); Watercolor and marker on paper. 15 x 20 in.

Your mom told me Diana Ross was haunting you? She said she had to exorcise Diana Ross from your room so you would stop painting her.

WS: That’s true. I still paint her sometimes but give her the name Linda Brown from Dreamgirls.

Who are you painting today?

WS: Halle Berry. She is a really beautiful actress. She’s from Hollywood. Halle Berry is the queen of the Skyline People. She is a humorous Skyline woman. Halle Berry will be humoring me with nice jeans, with a red shirt because Halle Berry is a powerful woman and she helps to bring people’s lives back, people who lost their lives.

She’s wearing some racy underwear…

WS: Yeah that’s right. Panty lines.

How long does it take you to make such detailed drawings and maps of the city?

WS: This plan took me five weeks to make.

And what would happen if all the William Scott paintings one day became real?

WS: The world would become a newborn baby.

(Laughs.) William, thank you for sharing your ideas with me. I enjoyed seeing your studio.

WS: Great! Thank you!

William Scott photographed by Daniel Trese for PIN–UP.

The interview with Scott in his studio leads to many more questions about his work, his thought processes, and his vision. I turn to Tom di Maria, Creative Growth’s longstanding director, who’s been accompanying Scott’s development for the past 17 years.

Some of the 20th century’s most influential architects were philosophers with a utopian vision, like Le Corbusier, Oscar Niemeyer, or Frank Lloyd Wright. Architecture was their tool for manifesting their ideas about a better humanity. That seems to be William’s thought process too.

Tom di Maria: If you think about William Scott as an architect, it extends beyond buildings. He invents social organizations, and creates new geographic hybrids — he’s an architect of the world. His definition of architect is somebody who invents new places.

The scope of his ambition is massive.

TdM: Yes. The world in his paintings is an amazing, beautiful place. The only thing that holds him back is the fact that he doesn’t have academic training or complex verbal skills. Growing up with disabilities, in a poor neighborhood with bad schools, the burn on his body, he was probably bullied a lot — he didn’t have a lot going for him, but he always had this enormous loving soul. There is not a negative thought in his brain.

William Scott, Untitled (2005); Ink on paper. 20 x 30 in.

He wants all people to have their own balconies so they are happier and act better. I once interviewed WOHA, an architectural firm in Singapore that’s famous for designing megastructures for public housing with as much green public space as possible. Their vocabulary is different but the instinct and reasoning are similar.

TdM: Sometimes we limit ourselves by thinking that people who don’t verbalize like us, or don’t have similar academic backgrounds, can’t have amazing ideas. You could ask William a hundred times where he got the words “Inner Limits” and he can’t give you an answer. My understanding is that he feels his disabilities limit him and he wants to move beyond those inner limits that he was born with into a place that is more expansive. I think he’s trying to transcend the boundaries of his disability. Creative Growth artists don’t have the academic or commercial concerns that most artists do. For William, making work is as essential as language. I sometimes think about where he’d be at if he didn’t work here. Would he still be making work?

I think he would be drawing but it wouldn’t be on the same scale. He wouldn’t have the materials, but more importantly he wouldn’t have such a high level of encouragement and emotional support. People might say, “Oh that’s cute,” but they wouldn’t have the context to understand how meaningful it is.

TdM: Right. For us it’s not about cute. It’s about creating a path for artists to express themselves without judgment. That’s part of our philosophy: we know that the power of the individual will come through if they are given a way to move forward.

When William writes a letter to the mayor, what do you think he hopes to achieve?

TdM: When William writes to politicians, it’s because he believes that they have the power to make his visions reality. The mayor is in charge of the Redevelopment Agency. Tiffany Bohee reported to him, so he goes to the top… For William it’s not about getting attention for his work, it’s about finding a way to have his designs realized. The paintings are a transformative tool — they lead either to the rebirth of a human being or to a building being built. He has never expressed interest in keeping his paintings. He doesn’t view them as precious objects. He sees them as plans for the future, plans for living. William often doesn’t finish work. I think he’s genuinely fearful that his ideas may not become real. There have been times when he’s said, “Why didn’t this change happen, why wasn’t this building built?” He thinks perhaps the painting wasn’t good enough. This has pushed him stylistically into a way of working that is almost hyperreal or very photorealistic. He feels that if the paintings are more accurate his plans have a better chance of being built.

He’s probably right. This may seem like a strange comparison, but after speaking with William I started to see parallels between his paintings and Tom of Finland’s drawings — especially after seeing William’s dancing cops. They aren’t killing anyone, they’re dancing! Tom of Finland’s work was also about revising reality, so that the institutions that currently oppress us participate in our pleasure.

TdM: Yes. It’s about turning the tables with respect to who has the power. Instead of seeing difference, William views us as being part of a dynamic to move forward together. And just like Tom of Finland’s, William’s work also has a fetish quality in terms of the heightened sensuality of the female bodies. I have this thing with William Scott paintings — when I look at San Francisco at sunrise I think, “Oh, that looks like a William Scott painting.” The painting for me is more real than the reality. It also comes back to your Tom of Finland idea of capturing the essence of the thing you’re depicting so that it becomes truer than the thing itself.

William Scott, Untitled (2006); Acrylic on paper, 15 x 20 in.

What I also think is interesting about William’s world is that he wants to update everything. Buildings should be newer, cleaner, and better than they are in the present. But sometimes those updates mean going back to the past. Time seems to collapse. Is that specific to autism?

TdM: No. William is on the autistic spectrum and there is a history of people with autism being able to record detail, having photographic memories. I think that’s where William’s attention to detail and his capacity to draw these articulated buildings from memory comes from. But because William is also schizophrenic, I think that’s the part that leads him to believe in the fantasized utopia. It’s the part of him that sees time as completely fluid. He will use the past tense and the future tense in the same sentence and doesn’t see a contradiction. “That was gone in the future,” or “That past will happen.” The verbs are rarely conjugated in a future or past tense. I think William remembers the future the same way that he remembers the past. Past and future changes are all equal to him in terms of changes that he hopes for or regrets. A burn to the body is a bad change, but his hope to go back to the hospital before the burn happened is positive because he can go back into the past and erase what will happen.

Does he look at other artists’ work?

TdM: He doesn’t have artistic influences, and I’ve never seen him look at other artists’ work. Back in 2009 he had a one-man show at White Columns in New York. He went there with his mother and sister and he didn’t want to go to the opening. He was having this one-man show at a hot New York gallery and it was the last thing he wanted to go to. He preferred to ride the subway and go to Times Square. The experience of life and the process of making the art are what fuel him.

William Scott, Untitled (undated); Acrylic on paper, 15x20 in.

Do you have a favorite William Scott piece?

TdM: For me it’s really about some of the self-portraiture. One of the portraits he made of himself as Billy the Kid is pretty amazing. The thought of going back in life and correcting your own destiny is fantastic, especially because he does it without regret. It’s not like, “I made a mistake” or “I wish I hadn’t.” It’s more about “I am hopeful for who I will become.”

Do you know where his idea of reincarnation spaceships came from?

TdM: I don’t know where he got the idea. The idea of resurrection and going to heaven may have started with the church. He’s not one for the artifice or the affect of religion. He gets right to the core and promotes the belief that everyone on the planet should support one another. He now has work in important collections: at the MoMA in New York, the SFMOMA, The Studio Museum in Harlem… If you think about an African-American kid growing up in the projects, who’s autistic and schizophrenic, and now has their paintings collected by MoMA, that’s such an incredible achievement. The chances are a billion to one.

Interview by Michael Bullock.

Portraits by Daniel Trese. All images courtesy Creative Growth Art Center.

Taken from PIN–UP 24, Spring Summer 2018.