TRACES, ECHOES, SKINS: Heidi Bucher’s Meditations On Memory

A 1981 film opens with a dark shot of a dreary corner, the plaster of the walls peeling from its brick structure, little natural light sneaking in from dirtied, shuttered windows. The camera tracks low, moving slowly through abandoned-looking rooms and cutting between different architectural fragments. The soundtrack is lugubrious, ominous — screeching sounds resonating into sonic expanse. Eventually we see feet, clad in heel boots, crunching over shattered glass. A flashlight flicks on. A full body isn’t shown, at least not yet. The film has all the feeling of a horror movie.

It turns out the echoing “music” is a recording of whale sounds and that the home will soon be the site of one of Heidi Bucher’s latex skinnings, a kind of echo too. It’s fitting the film felt at first like a slasher flick, as, after all the late Swiss artist made ghosts. Or at least made ghosts visible. The film’s title: Raume sind Hullen, sind Häute (Rooms are husks, are skins).

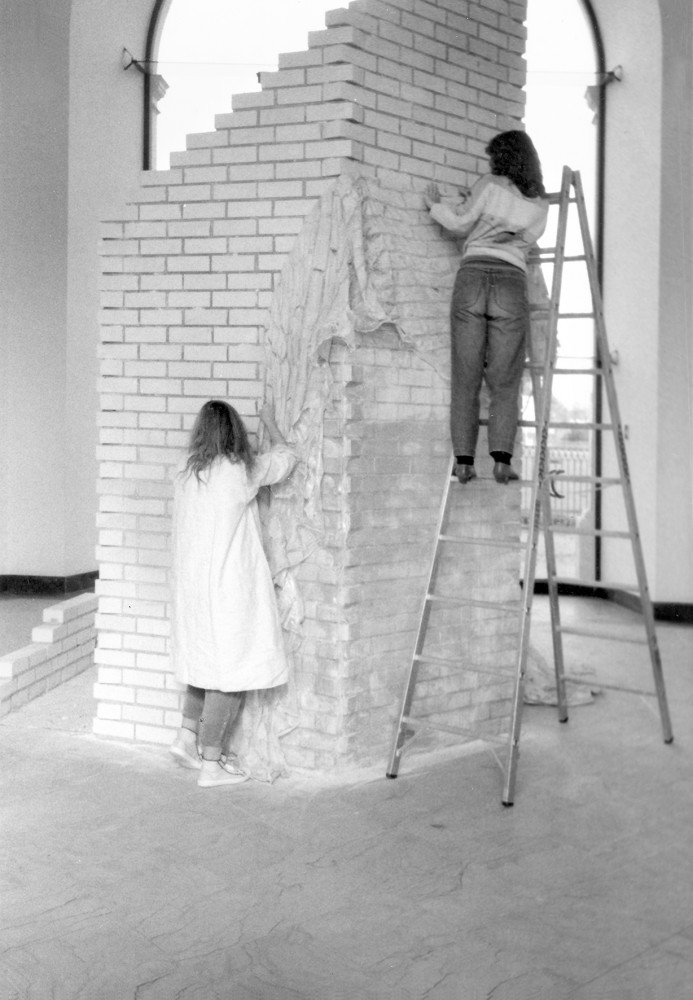

Heidi Bucher, Elfenbornhaut, Fridericianum, Kassel (1982): latex, textile, and mother of pearl pigment. Photo by Matthew Herrmann. © The Estate of Heidi Bucher. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul.

After her death in 1993, Heidi Bucher remained relatively unknown to much of the art world outside of her native Switzerland. Over the past decade, however, there’s been a much-deserved resurgence of interest in Bucher and her work — including a 2018 show at London’s Parasol Unit, a 2014 retrospective at Swiss Institute, and most recently, the current exhibition at one of Lehmann Maupin’s New York locations.

Heidi Bucher: The Site of Memory, which closes Saturday, displays many of Bucher’s own “memorials:” pearlescent and brown latex skinnings that she produced from the mid-1970s to the late 1980s. Upon walking in, however, one of the first works that greets you is not one of her distinctive room skinnings, but rather, a jumpsuit, draped from a rusty hanger, tattered and worn, but alive with the mother-of-pearl pigment Bucher was so fond of. It’s titled Der Schlüpfakt der Parkettlibelle (The hatching of the parquet dragonfly). Though not the earliest work in the exhibition, which stretches back to 1975, it still makes sense as a starting point. It represents the most urgent beginning: the body. Empty and frozen, it also shows that body’s — or really any body’s — absence. It displays what it isn’t.

Heidi Bucher, Der Schlüpfakt der Parkettlibelle (The hatching of the parquet dragonfly) (1983): textile garment, latex, and mother of pearl pigment. Photo by Matthew Herrmann. © The Estate of Heidi Bucher. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul.

In the 1940s when Bucher trained at the Zürich’s School of Applied Arts, a Bauhaus-like organization, she and many women like her were relegated to the more traditionally “feminine” artistic and craft practices. She took up fashion. Some of her work, this jumpsuit included, more directly followed this tradition, enlivening objects as one enlivens the garments one wears. There is a particular film from 1972, Bodyshells, in which a stationary camera watches four people totally covered in silver “shells,” something like space-age reimatinations of Art Nouveau vases, wobble about the Venice Beach. (Bucher was living in Los Angeles at the time, and it’s hard to think of her work without its formal dialogue with post-Minimalist artists living and working in the U.S.) A lone person in the distance sits watching the tide. There are photos of Bucher draping herself in the skinnings, wearing them like some sort of cocoon. One wonders what she hoped to turn into.

Her later building work is no less embodied than these post-fashion pieces. Making the skinnings is hard. Laborious. Watching old footage, like the uncanny art film we began with or a more straight-documentary work of her skinning the doors of the Grande Albergo, an abandoned hotel in Brissago, which served as a gathering place for displaced intellectuals during the Second World War, one can see the intense physical labor the skinning takes. It’s not just coating the structure with latex but the very physical — almost violent — act of peeling it away, struggling against the material to pull at first small chunks with fingers, and then leveraging the strength and weight of the whole body to skin and unskin the structure itself. It’s amazing the latex comes away whole.

-

Heidi Bucher, Ablösen der Haut II – Herrenzimmer (1979). Photo by Hans Peter Siffert. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul.

-

Heidi Bucher, Ablösen der Haut II – Herrenzimmer (1979). Photo by Hans Peter Siffert. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul.

Some say Bucher skinned fraught places — prisons, sanitariums. But what place isn’t fraught? Life happens in, through, and because of place; each site and plot of earth is a contested site that we form in our own memories and with our own bodies. One salient piece is a skinning of her father’s study, a room which in German bears the appellation Herrenzimmer, men’s room, a word which is left to remain in the English title of the piece Untitled (Door to the Herrenzimmer). However, in the 1978 piece, it is not the room she took and made her own, but its doors. She claimed the entry and yet the entry remains just as unenterable, if not more, than the “men’s room” that the real doors once cordoned off.

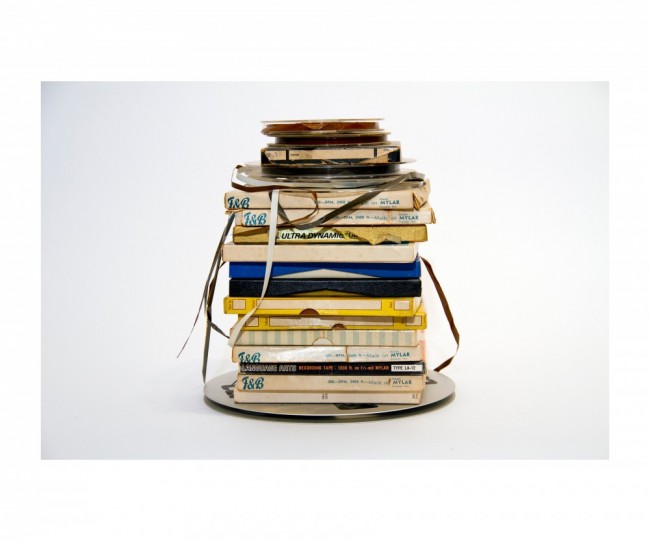

Memory lives — or is fabricated — in other ways, too, ancestry among them. Bucher’s father was an engineer and she grew up going to construction sites. Her sons, Mayo and Indigo, who came to New York for the exhibition’s opening, worked closely with her as studio assistants and to this day oversee her archives. “She loved old houses,” Indigo Bucher recalled at Swiss Institute in 2014 during a conversation documented in the exhibition catalogue. “She loved antiques — not expensive antiques, but traces, used things.” Perhaps, we can understand the skinning as a form of collection. “She loved abandoned things.”

For all the seeming of wanting to make something that once was (a family home, a defunct hotel, a column from Europe’s oldest public museum) last, Bucher’s works don’t. Or not exactly. Latex is a notoriously troublesome material. It, like us, decays. It hardens and changes. Whole new fields of artistic conservation have popped up around the many materials contemporary artists have taken up, latex among them (think Eva Hesse or Richard Serra or Louise Bourgeois). But Bucher knew this. She loved traces, as Indigo says. She made traces. She loved then abandoned things.

The pieces on view at Lehmann Maupin, like most of Bucher’s oeuvre, bear witness to our variegated ways of occupying, experiencing, and remembering space, of course, but more directly they present the life and memory of buildings themselves, their own traces. The latex doesn’t just take the form and shape of walls and rooms, but drags away the patina from their surfaces — the dust and dirt and grease collected, the wounds these structures have endured. Her work then, in its collection and transference, is a cleansing, a refresh like a snake shedding its skin. It’s also a kind of evidence.

Heidi Bucher: The Site of Memory (2019), installation view. Photo by Matthew Herrmann. © The Estate of Heidi Bucher. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul.

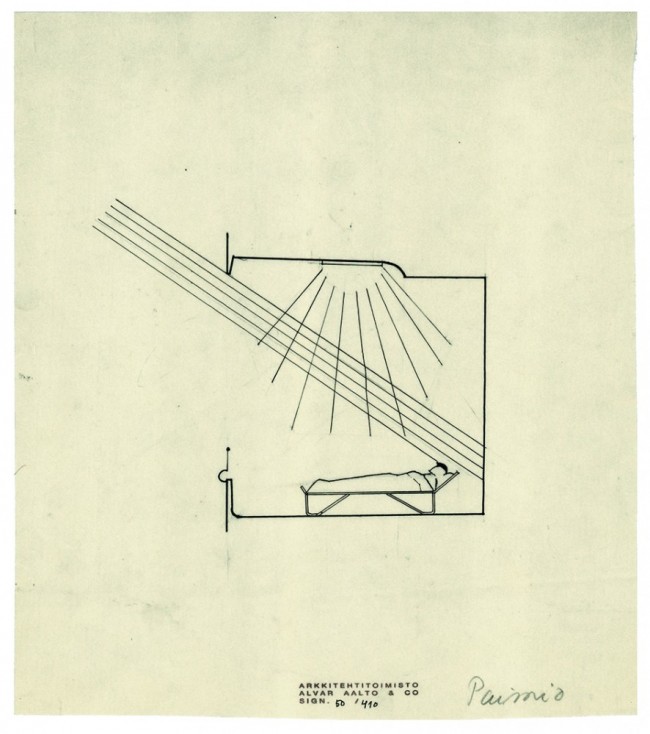

And to speak of skin is to speak surfaces and what it is to make space flat. Of course some works, like the sculptural Borg, are more directly architectonic, but others like the Herrenzimmer skinning and Fenster mit Läden und Schindeln, Bellevue, bear a defining surfaceness. Bett (Bed), another piece made for the body, is rendered flat and placed on a wall, its verticality making it useless, like the other impassable doors. The 1982 piece Elfenbornhaut, Fridericianum, Kassel takes a four-sided support column and unfurls it into a two-dimensional hanging marred with the patterns of bricks, its top uneven. Walls on walls, these skins are stretched and hung like trophy pelts that have been scored hunting for the things architecture witnesses. And there is painterliness to them, too. Untitled (Puerta beige grande / Large beige door) is even on canvas. In all the works shown at Lehmann Maupin, the latex is tinted and colored, decorated with phosphorescent nacre and purples and browns, it’s treated not exactly as canvas would be by a contemporary painter, but as something to be illuminated, like medieval manuscripts — documents too and also made of (literal) skin. Bucher’s skinnings are colored as if to bring out a life already residing there.

And with life there is death. With birth, mystically, rebirth. The initial garment, Der Schlüpfakt der Parkettlibelle (The hatching of the parquet dragonfly), is named after her anisopteran fascination. Earlier, in 1976, she had realized a costume, latex and textile and mother of pearl, also of that bug, called Libellenkleid (Dragonfly costume object). It was more literal, a creepy abdomen sprouting four wings. In the 1983 piece, the dragonfly becomes at once more or less metaphor. The human body does not need to don wings to become something else. It is already everything that it isn’t. It is noteworthy that it is titled after the hatching, when the larva, called a nymph, after those divine animators of nature, crawls from its egg towards the promise of some beginning. Shimmering and quick, they look something like fairies, like the mother-of-pearl colors and piscine scales that decorate Bucher’s skinnings, decorations so fantastic that they could only be made by nature. Der Schlüpfakt der Parkettlibelle hangs eerie and absent, a skin shed of its body like the other skins shed themselves of their buildings. All dragonflies are predators, even just after leaving their eggs.

Text by Drew Zeiba.

All images © The Estate of Heidi Bucher. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul. Installation photography by Matthew Herrmann.