NIGHTLIFE ARCHITECTURE: From Times Square to The Spectrum, What We Get Out Of Going Out

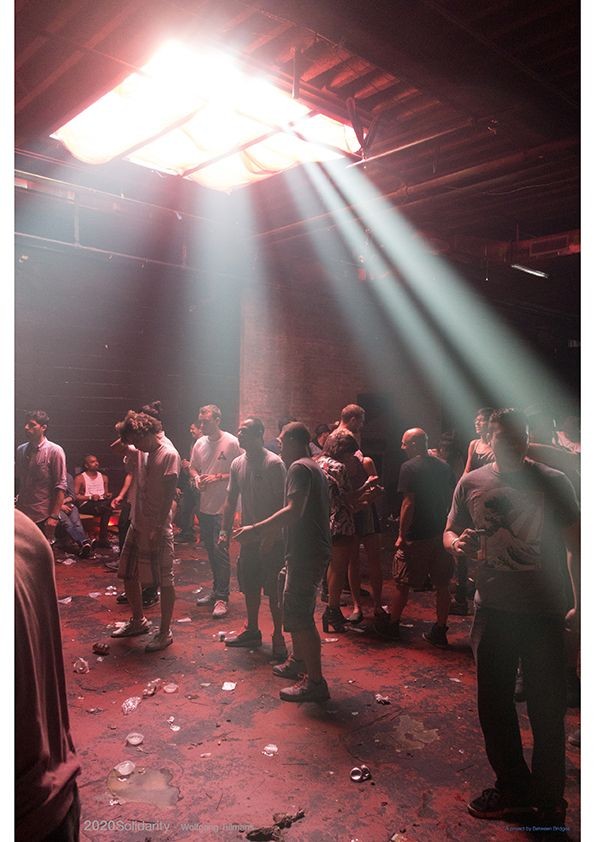

Inside Spectrum club’s second iteration in Ridgewood, Queens. © Daniel Terna

When you go out, do you want to ______?

a) be seen

b) not be seen

At nightclubs, I often want to get lost. I want low, minimal lighting. I want a sound system so powerful I’m compelled to dance. I want fog. But I may also want to catch your eye. To see you make an entrance, feeling yourself. I want to look good. I want to know I’m in New York City.

I think of nightclub design as an exercise in fantasy building. It is an architecture of experience. The spatial arrangement of a club, the materiality of its walls, and the attractiveness of its lighting should make you feel a certain way. A good club transports you. It displaces you from normal life. Form follows fantasy.

So sure, I accept the cliché: if you can get past the door of a club, you may discover an alternate world. But in that club space, do you feel glam? Do you feel free? Maybe both. And maybe not. It’s in the design, and, importantly, it’s in you.

At 47th Street and Seventh Avenue, across from the Olive Garden, under some dingy scaffolding is the entrance to Paradise. The club, located within the newly built Times Square Edition Hotel, is Ian Schrager’s latest foray into the hospitality-as-nightlife and nightlife-as-hospitality template he has honed in his decades-long journey from Studio 54 impresario to globe-trotting hotelier.

Murals by En Viu Studio at the Times Square Edition’s Paradise Club. Image Courtesy Edition Hotel.

On opening night in the spring of 2019, celebrities and grifters temporarily replaced wide-eyed tourists and Elmo on a stretch of sidewalk in New York’s Disneyfied hell. The door was hard. Club kids in platform shoes and girls with tiny Telfar bags clamored to get inside what a press release called “the best thing to hit Times Square in over a century.” In a welcome gesture of nightlife nostalgia, Diana Ross gave a surprise performance, inaugurating this Schrager venture, just as she had closed out Studio 54 back in 1980. As the open-bar flowed, the done-up crowd cycled up and down back stairways discovering floor after floor of sleek bars and palm-appointed terraces. Here, in the middle of Times Square, was an oasis. It was 1978; it was Miami; it was a movie you saw before you moved to New York. Pick your fantasy, just make it chic.

Everything about the Times Square Edition is designed to make you forget where you are. Interiors designed by Yabu Pushelberg emphasize botanicals and a neutral color palette in “ultimate counterpoint to the surroundings,” according to the press release. The 47th Street entrance intentionally excludes and elevates. Opaque doors, ivory plaster walls, and a Jeff Koons-esque orb signal to those who enter: this is a “refined” space. Yet the interiors do more than weed out the Benihana crowd — they transport you. Thousands of plants, trees, and ivy in the upper terraces — what star landscape architect Madison Cox calls “multi-level gardens in the sky” — make you forget Times Square’s concrete mess below. If good club design takes you somewhere otherworldly, then sipping an 18-dollar cocktail in a jungle of enormous ferns, next to a jumbo LED screen, would probably qualify.

Performers at Times Square Edition’s Paradise Club. Image courtesy Edition Hotel.

The Edition is effective because it appeals to the very New York fondness for gross contradiction. I love to hate Times Square, so give me paradise in hell. Yet rather than let the well-executed sensory whiplash of the Edition’s design act by itself, as it did on opening night, Paradise Club now carefully programs the fantasy experience it thinks you want to have. A high-production neo-burlesque show by Bushwick’s glitter-loving House of Yes draws finance types and tourists seeking a campy Manhattan experience without the intimacy or door policy of longtime downtown nightspot the Box. With a performance inspired by William Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, the dinner show features impressive sword-swallowing circus-like acrobatics, break-dancers, and an exhortation from the MC to “lose yourself to the night.” Yet, served “caviar nachos” with chopsticks while a slowed-down cover of Nine Inch Nails’ “Closer” played, I began to feel more and more stuck, like the twisted creatures of purgatory in the Bosch-inspired murals Schrager commissioned to line the walls of the club (by En Viu Studio). Instead of performing my own glamorous Manhattan fantasy, I was being fed a commodified version I did not want.

In an interview for the book Night Fever: Designing Club Culture, Schrager explains how at Studio 54 he intentionally separated the dance floor from the rest of the interior in the same way the seats of a theater are distinguished from the stage. The dance floor was itself a stage, and all had a role to play in each night’s unraveling production. At Paradise Club, he scraps this notion. In place of the dance floor, sequined entertainers death drop under a kinetic “ceiling starburst LED light feature” amid a sea of 195-dollar-a-seat prix-fixe tables. You are no longer the performer in this nightlife space but, thanks to the iPhone, you can still be a performer in your own nightlife story. Just make sure to tag @timessquareedition, because this architectural space is designed to be exclusive but widely shared. In fact, while you broadcast the experience to your followers in five-second snippets, a 17,000-square-foot jumbotron on the hotel’s exterior façade will live-stream the party for the tourists thronging below. This is the architects of this nightlife experience whispering: you did not come to this club to escape; you came here to be seen.

Performers at Times Square Edition’s Paradise Club. Image courtesy Edition Hotel.

One borough over, and many stories down, a very different vision of nightclub design can be found in the basement of a century-old glass factory in Maspeth, Queens. The club — simply called BASEMENT — is industrial, dark, and perfect for the musical genre spun there: techno.

About a year ago, while working for Knockdown Center (the music and arts venue now occupying the former factory space) the creative team behind the club — Tea Abashidze, GeGa Japaridze, and Tyler Myers — realized the potential lying right under their feet. Without the assistance of star designers, PR teams, or paid performers, the trio repurposed the network of brick tunnels under the industrial space into what is claimed to be New York’s first club dedicated exclusively to techno. If Schrager’s Paradise Club is an overwrought surrealist tableau, BASEMENT is a delightful objet trouvé.

Low-arched brick ceilings bring cold intimacy while a maze of thick columns creates nooks for discovery and sex. A lone illuminated smokestack towers over smoking clubbers outside. Even a quasi-Brutalist concrete entrance ramp — offering an iconic shot for DJs’ Instagram feeds (no photos insideplease!) — predates the conversion to club.

Entrance to BASEMENT club at Knockdown Center in Queens. Image courtesy the Knockdown Center.

Cool kids in Brooklyn have moved from Bedford Avenue to Myrtle Avenue, from indie bands to DJing, and from flannels to sportswear — and now, finally, there is a space for them to live out their Euro-techno fantasies. Almost effortlessly, BASEMENT looks the part. Thanks to a Funktion-One sound system, dim lighting, and minimal strobes, it feels the part too. The (way-too-white) Berlin-based opening line-up and blocky black-and-white graphic design also contribute to a particular am-I-at-Tresor-or-is-this-Queens? sensation.

When I meet Abashidze and Japaridze during off hours to chat, they are keen to emphasize how their vision for BASEMENT is deeply shaped by their experiences growing up in Tbilisi, Georgia. “After seeing two wars, constant protests in the streets, homophobia, sexism, and many other bad things, our generation wanted to create a different, freer world,” Abashidze tells me. “Techno has helped to create that world.” Tbilisi’s most famous club, Bassiani, is located in a drained swimming pool under a Soviet-era football stadium — a Brutalist safe space and a catalyst for the country’s booming tourism industry. In Georgia, they tell me, a club is not indulgent but urgent. When Japaridze hears the word “techno,” he associates it with “freedom.”

The times I go to BASEMENT, I go happy not to be seen. This space is about techno. A proper club. It’s about the music and me. It’s about dancing for myself, not for others. According to Abashidze, “the reason the lights are minimalistic is to give you intimacy and privacy. You can find yourself where you want to be, and not be disturbed.” Here is a new type of built fantasy. A solitary one.

Whether high-rise or basement, Manhattan or Brooklyn, 2019 or 1979, nightclubs are design laboratories for our fantasies. Looking around — feeling around — Paradise Club and BASEMENT, I notice not only two different architectural spaces, but two radically different visions for why we go out. In New York City, this tale of two nightclub typologies is hardly new: if the 1970s was the worst of times economically, it was the best of times for nightclub experimentation.

As an architecture that structures experience, nightclub design is rooted in technologies that play with the senses. The modern discothèque emerged in the mid-20th century when sound systems replaced live bands. Experiment with lighting, add a generation of sexually-liberated people, and you see the early components that constitute the technologically-saturated artificial environments we know as clubs today.

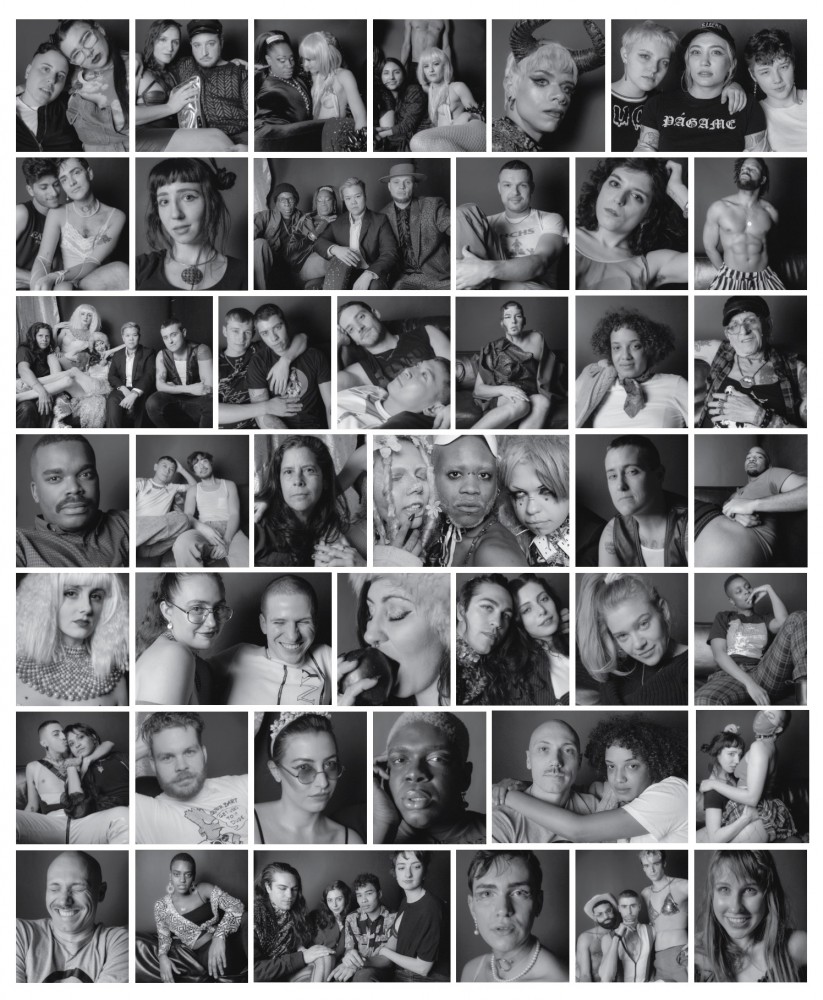

Partygoers during the closing night of Spectrum’s Queens location. © Daniel Terna

In 1970, inside a second-floor loft at 645–647 Broadway in the Village, David Mancuso pioneered a new prototype of nightlife space. At the Loft, as it came to be known, “minimal lighting effects encouraged dancers to focus on the connective experience of hearing rather than the separating experience of seeing.” Mirrors were removed and photography was prohibited in order to encourage dancers to overcome self-conscious inhibitions. Mancuso placed the main speakers along the wall opposite the turntables so that dancers faced each other, not the DJ booth.

It was nothing like a rave: no strobes, no body thrashing, no techno. Yet, in Mancuso’s dogged vision of sonic purity and spatial minimalism we see the origins of both a nightlife ethos and an approach to achieving it through design that would go on to influence a whole crop of private parties of the era — the Gallery, Paradise Garage, the Warehouse — and underground dance-music cultures since then.

In a 1999 interview, Mancuso reflected that “the one thing the Loft did do was set a standard for getting your money’s worth: a decent sound system. I wanna hear the music. Once you hear the sound system that means you’re getting ear damage, ear fatigue. So you want music, not the system. Same with lighting. You don’t want fatigue.” Today, if you enter famed techno-temple Berghain, your phone camera is symbolically covered and there are no mirrors in the toilets. The club is designed for you to stay there for a very long time. It’s about the music. You get your money’s worth.

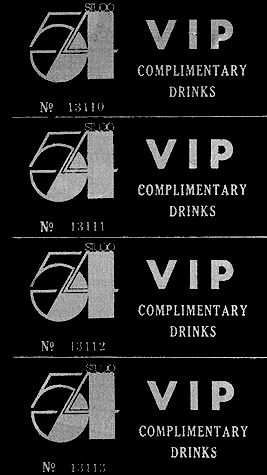

Starting in 1975, a few years after Manusco brought his vision to life, Schrager and Steve Rubell honed a different vision of nightclubbing uptown. Compared to downtown parties like the Loft, Studio 54 looked different and felt different. Rather than emphasize music and the collective experience of dancing, it was the ultimate venue in which to see and be seen. Like Berghain, it was famous for its hedonism and for those individuals who did not get in. Yet, far from minimal, Studio 54 assaulted the senses with spotlights, confetti, glitter, a computer-controlled bridge, and the “flying ceiling” (28 rotating mirrored panels crisscrossed with pink neon tubes). Schrager explained in a recent interview how “the combination of architectural lighting and theatrical lighting created a space which made people look and feel good — it was the linchpin of the club’s success.”

In New York, fantasy, like most things, is big business. Schrager has stated that “designing a nightclub is more about architecture than anything else, because you don’t have a product to sell. All you have is the design, architecture, and proportions.” Therefore, extending his business logic, a nightclub should be designed to sell an experience. Elements of the glitz and glam sold at Studio 54 live on in many Manhattan clubs today. Tim Lawrence, author of several books on nightlife culture, calls Studio 54 “significant for popularizing a form of narcissistic, hierarchical, flashbulb-oriented discothèque culture that valued celebrity spotting as being seen above dance-floor abandon.” Make an appearance at Studio 54, and you may have just ended up on Page Six. Make an appearance out today, and you may become an Instagram influencer. The fantasy is aspirational and individualistic. People pay 1,000 dollars a bottle for it. Nouveau club kids spend days crafting looks to be part of it. To go out in these spaces is an architectural experience that feels quintessentially New York, even if you hate it.

Obviously, nightclub design is no binary. The typologies of both the showy commercial club and the downtown underground loft permutated and diversified just as the city transformed. New music, new crowds, new technology, new drugs… new fantasies.

We see people brand new people

They’re something to see

When we’re nightclubbing

Bright-white clubbing

Oh isn’t it wild?

— “Nightclubbing,” 1977, written by David Bowie and Iggy Pop

Whether sung by Iggy Pop in 1977 or Grace Jones in 1981, the implication remains the same: seeing people constitutes an important part of the nightlife experience. By thinking of the dance floor as a stage at Studio 54 — with all its accompanying flashy touches and celebrity sensibilities — the club’s design team acknowledged a plain fact: for many people, nightlife is performance. Clubs are radical architectural spaces because they allow people to experience, however fleetingly, an alternate world in which to play with alternate identities; a built environment for the performance of aspirational, hedonistic, or more loving versions of themselves.

Starchitect cachet and a velvet rope can make a club feel glamorous, but the spatial distribution of glamorous nightspots in New York tracks neither the income of the partiers nor the luxury of the interiors. For many New Yorkers who are marginalized due to race, class, sexuality, or gender, the club is an essential space to assert personal identity, to be recognized, and to be fabulous. In the words of Junior LaBeija from the 1990 documentary Paris Is Burning: “O-P-U-L-E-N-C-E: Opulence! You own everything. Everything is Yours.”

Partygoers entering the queer community-run club Spectrum. © Daniel Terna

The recently shuttered Spectrum was one of those rare New York nightlife spaces where you could feel totally free. You would enter and feel powerfully transported to another, better, queerer world. The illegal club and community space, which reopened in an eccentric banquet hall in Queens after its first row-house iteration closed in 2015, had an architecture that would make you feel glam, disinhibited, and performative. At Spectrum’s closing night in January 2019, partygoers in looks unthinkable posed against iconic diamond-patterned padded-vinyl walls or danced furiously under the oversized disco ball and tacky chandeliers. Dismembered mannequins basked in phosphorescent glow; the basement bathroom was overflowing; a gaggle of queens perched in plastic Barbie Dream Cars.

A far cry from the industrial minimalism that characterizes BASEMENT, Berghain, or Bassiani, Spectrum offered a dizzying, colorful visual experience. As a nightlife space valuing performance, its design allowed for change and community use. gage of the boone, who founded Spectrum in 2011, explained to me that the space’s ephemeral quality was both a blessing and its biggest challenge. “The malleable aspect of the space mirrors the dreamscape we embody as a house that is full of dreams, constantly shifting from one to the next. It’s an ever-changing adventure over time, a collective journey.” Inside Spectrum, fantasy was not programmed; it was performed by you, and you, and you.

Earlier this summer, I spoke with Madison Moore after he played a rave that stretched deep into the morning in the back lot of a Queens warehouse. Madison is a DJ, professor of queer studies, and author of a recent book called Fabulous: The Rise of the Beautiful Eccentric. Despite what an interior designer or a PR agency might tell you, “fabulousness doesn’t take a lot of money,” according to Moore. Instead it “requires high levels of creativity, imagination, and originality; it’s dangerous, political, risky, and largely practiced by queer, trans, trans-feminine people of color or other marginalized groups; it’s about making a spectacle of oneself in a world that seeks to suppress and undervalue fabulous people.”

In nightclub design, Moore sees a tendency to democratize the experience of feeling “opulent, rich, even aspirational.” He cites ball culture, of which he is a part, but also the first luxury apartment hotels in the 1880s in New York. “They made it possible for anybody to feel rich. All you needed was enough money for the door, or a meal, to participate in the fantasy.”

Village Raid DJing at the Spectrum. © Daniel Terna

In a city dogged by capitalism’s incessant grind, it makes sense to want nightlife spaces that imagine success within it, and escape from it. When I want to feel on top of the world — like “I’ve made it” — I can go to Le Bain at The Standard High Line for a rooftop sunset drink, the skyscrapers of Manhattan stretching out to the horizon. Or, if I want to run away from the city’s money-obsessed churn and feel punk about it, I can go to a graffiti-covered basement bar, or uncover a warehouse rave.

Nightclub design may derive from particular visions of why we go out, yet, like all architecture, it is fundamentally shaped by economics and regulation. Until a grassroots effort spurred by bars, nightclubs, and community groups in 2017 repealed the antiquated Cabaret Law in New York, dancing was banned at venues without a license. Regulation accentuated the design dichotomy between the commercial nightclub and the ephemeral DIY spot: you were either big-money legal or fully underground. In the years since repeal, a spate of well-designed, high-concept former factory, warehouse, and basement spaces have opened as fully-legal above-board venues. Moore tells me that he sees “1990s nostalgia inherent in these spaces — a nostalgia for the darkness, the messiness, and the excitement of partying in spaces that were not made for it — the excitement of trespass.” Nowadays, the fantasy is legal and can be purchased for 30 dollars on Resident Advisor.

Since Spectrum closed, my favorite underground parties take place at inadequate but exciting spaces with nicknames like “the Chicken Shop” and “the Cottage.” They are spaces designed for daytime utility, not nighttime fantasy. They are sweatboxes with fast techno and incessant fog machines. Inside I lose myself, but when I step outside — into the parking lot, or under the elevated train — I find myself, and a community. In the creeping dawn, ravers take a break from the party to catch up, flirt, and parade their identities. No architect designed these DIY spaces to satisfy this urge, but we make do in the improvised concrete living room that is the city.

Within these liminal urban spaces that blur the lines between our actual and imagined selves, between what’s socially permissible or not, we may discover an alternate world. The experience is shaped by the design, but most importantly, it’s shaped by us. Often, I picture the music video for the 1978 dance hit “You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real).” Sylvester emerges, falsetto soaring over a four-on-the-floor groove, hip swaying, dark skin glistening in a red sequined dress, with poise. Sure, it’s 1970s America, but this is an other place: a discothèque. Here, within this great experimental space of society and self, form follows your fantasy. And if you’re lucky — between the flash of a strobe, or a heartbeat — it feels real.

Text by Andrew Pasquier.

Taken from PIN–UP 27, Fall Winter 2019/20.