DRAWN TO LIFE: The Early Work of Arakawa and Gins

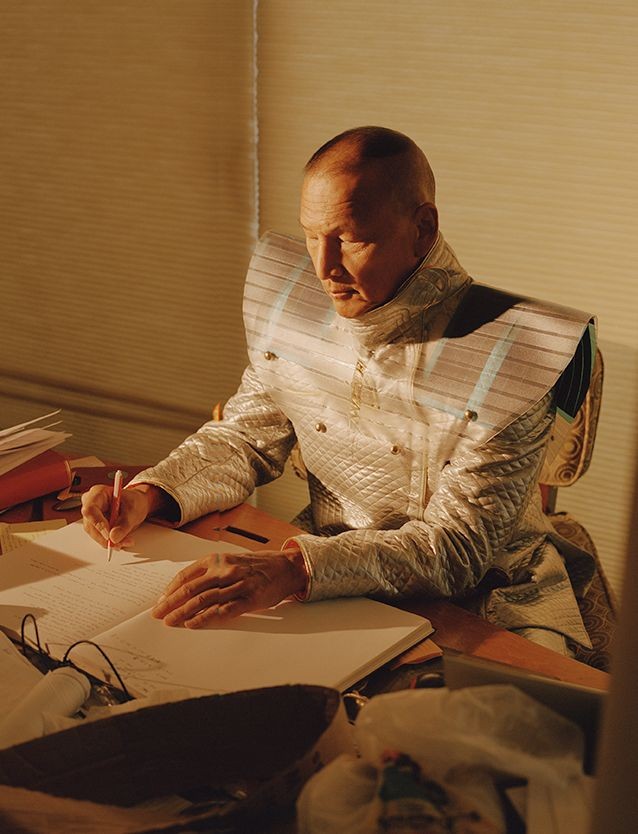

In the many writings by the late artists and architects Arakawa and Madeline Gins (Arakawa and Gins for short), humans are “puzzle creatures” who can only grope in the dark to understand themselves and their surroundings better. To get anywhere, people must make a practice of breaking apart their sensory faculties and reassembling them. While Arakawa and Gins, who died in 2010 and 2014 respectively, are widely known for their topsy-turvy built projects like the Reversible Destiny Lofts (2005) or the Bioscleave House (2008), their unbuilt paper projects from the 1980s have never been seen before. It is these that are currently the star of Arakawa and Madeline Gins: Eternal Gradient, on show at Columbia University’s Arthur Ross Architecture Gallery. Curator Irene Sunwoo, Director of Exhibitions, and Tiffany Lambert, Assistant Director of Exhibitions, found the works while digging through the archives at the Arakawa and Gins’s Reversible Destiny Foundation. “Very few people know about this part of their output,” says Lambert, who expresses particular interest in this transitional period in the artists’ oeuvre, when they evolved from tongue-in-cheek conceptual art to architectural renderings that show how spatial design has everything to do with perceptual reconfiguration.

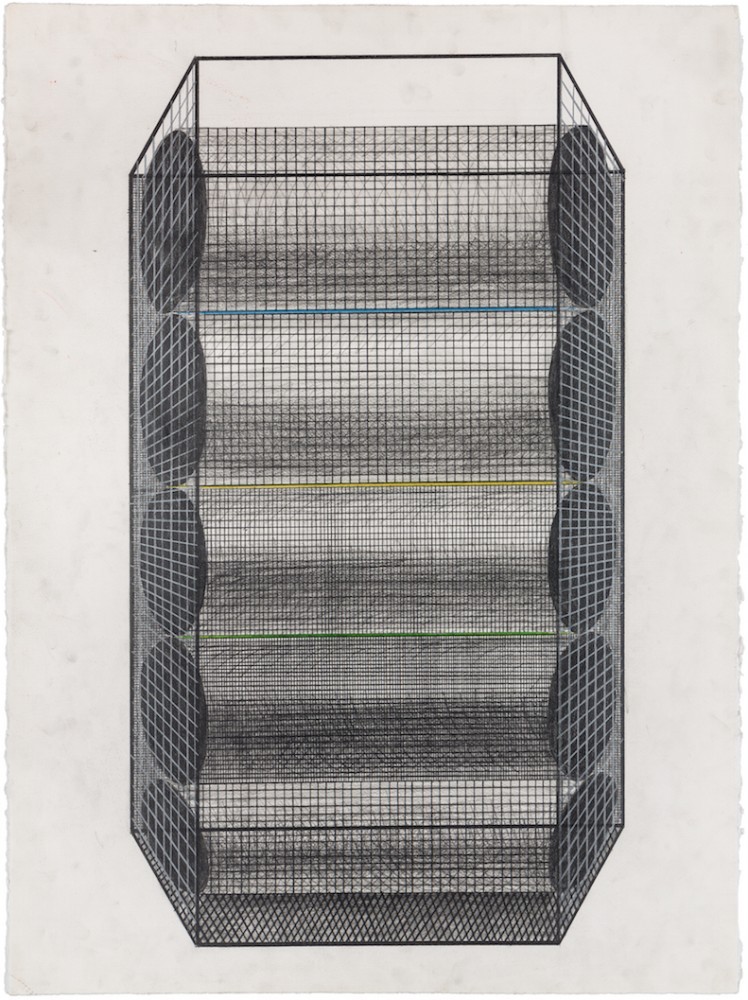

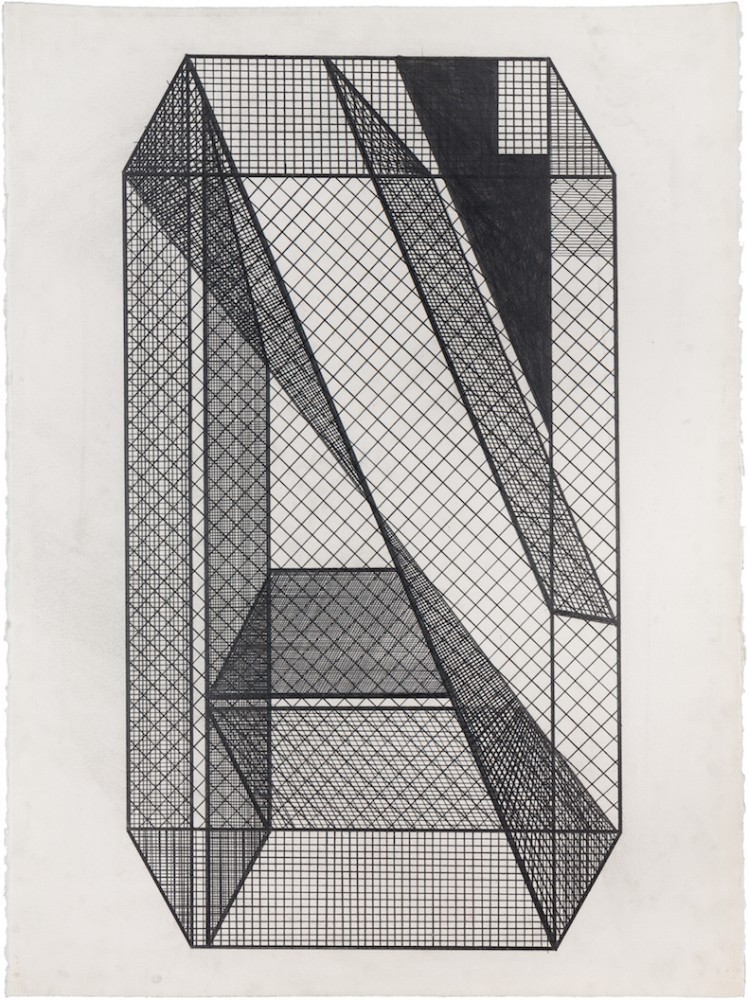

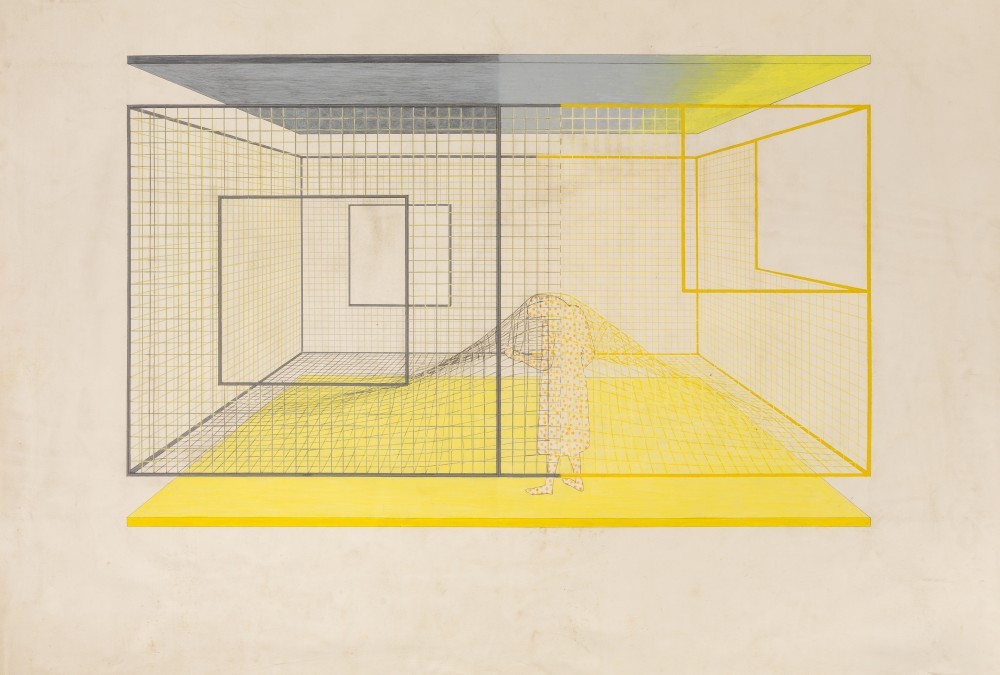

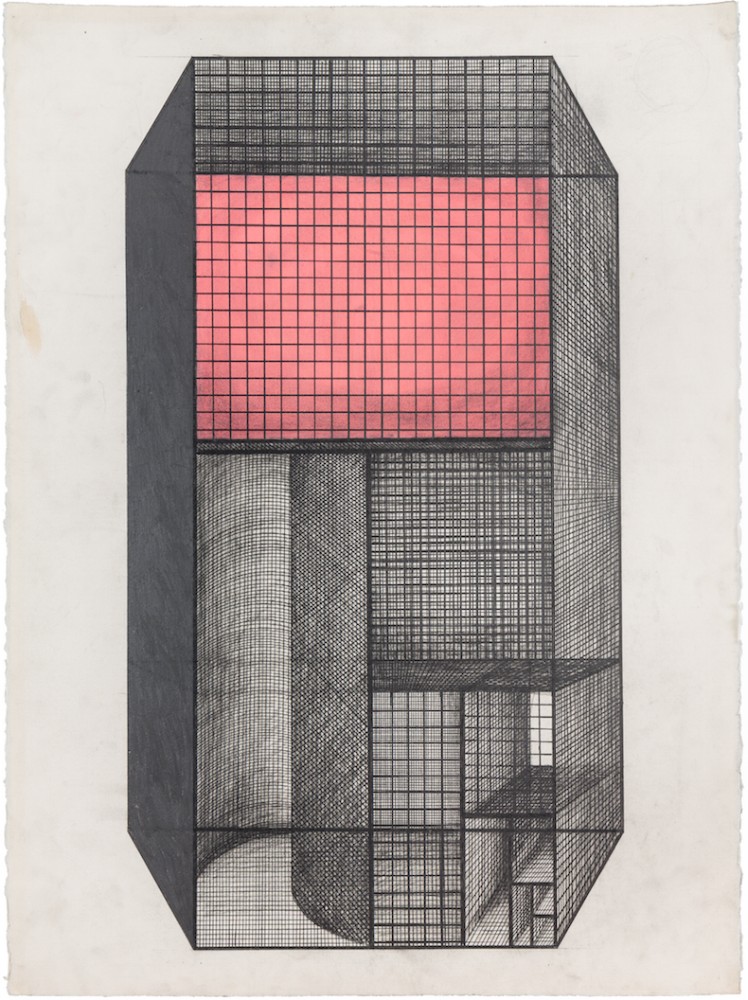

Arakawa and Madeline Gins, Screen-Valves, 1985–87; Graphite and acrylic on paper. 30 x 22.5 in.

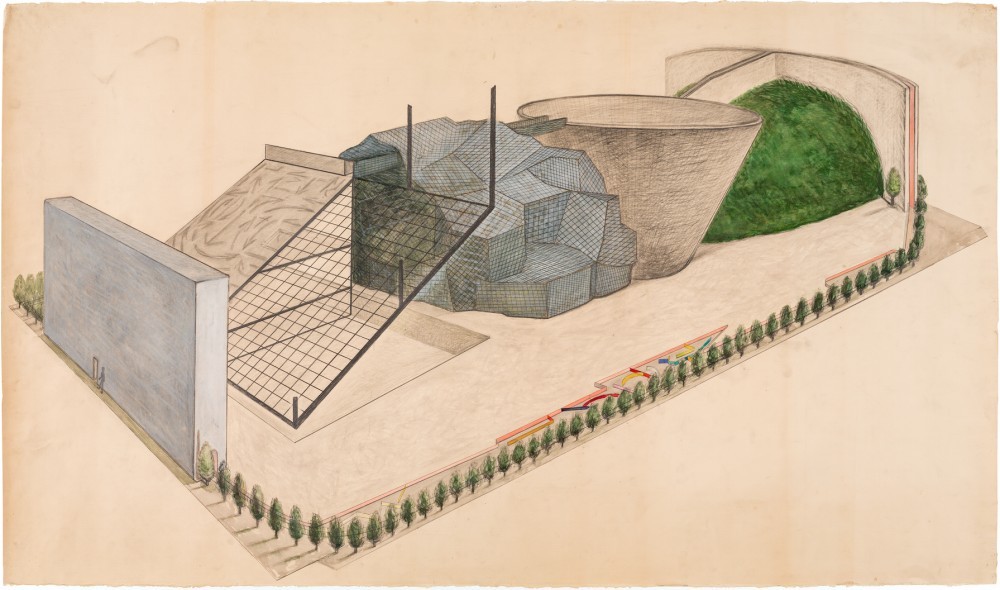

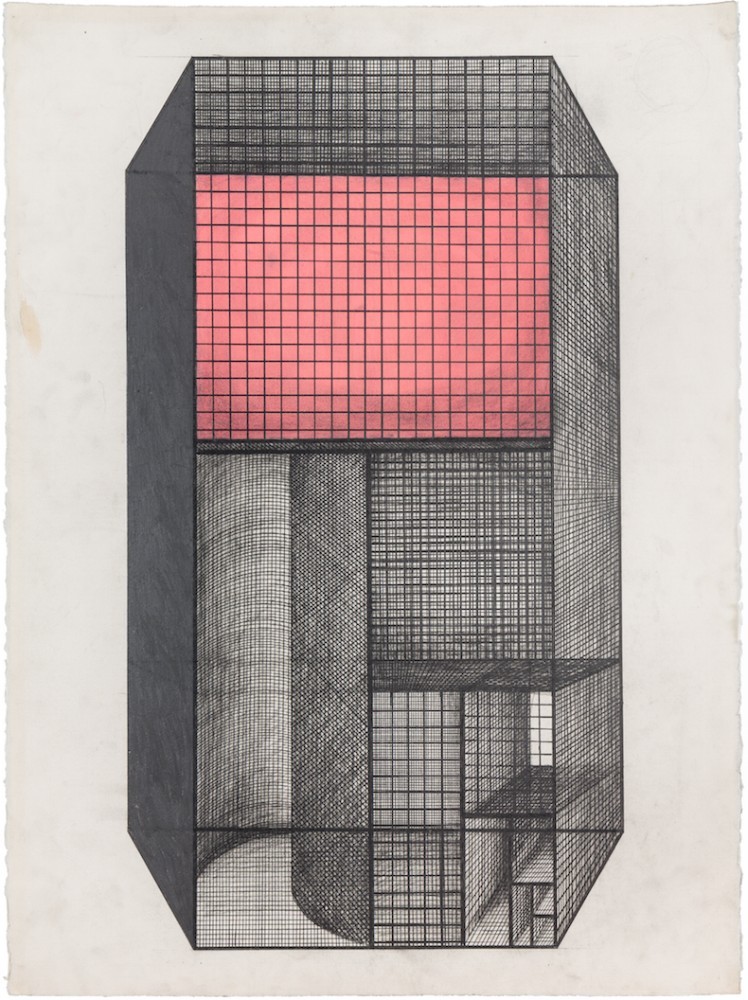

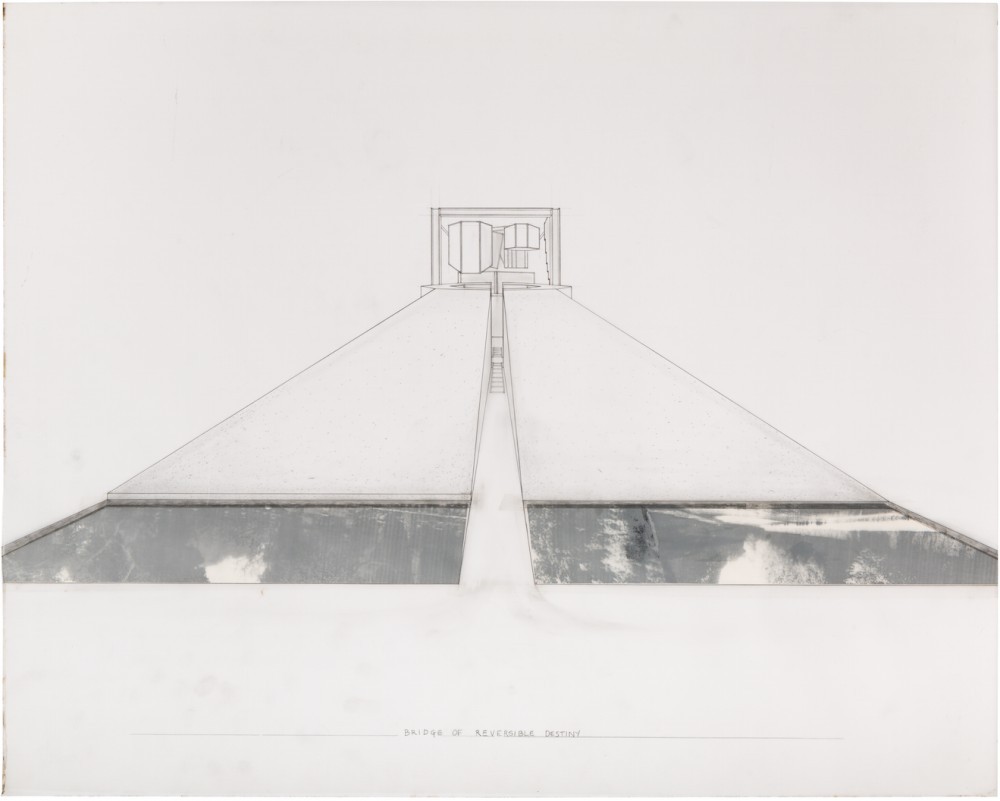

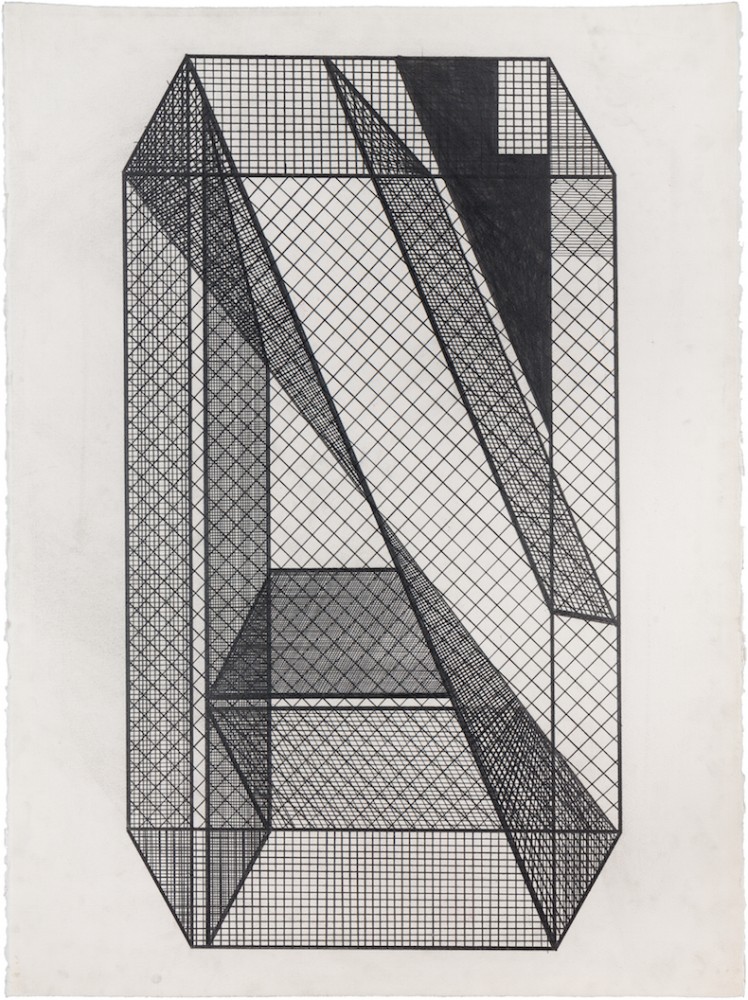

Working with the visual motif of the grid prevalent in Arakawa and Gins’s drawings, the exhibition’s designers, Chicago-based firm Norman Kelley, created four freestanding steel mesh structures displaying the late artists’ works. Each mesh structure displays a different series beginning with Screen-Valves (1985–87), a collection of 24 graphite drawings that include shapes, grids, and rooms within the same stretched octagon frame. The exhibition moves from these simple modular drawings to more fleshed-out structures depicted from multiple angles, concluding with The Process in Question/Bridge of Reversible Destiny (1987-1990), an early manifestation of the artists’ idea that architecture could be used to fight mortality, which later took on built form in projects like the Site of Reversible Destiny in Yoro Park, Yoro, Japan (1995). The gallery’s walls carry more drawings, many up to 8 feet wide, which entirely immerse the viewer, mixed with clippings from the artists’ research into blindness and anatomy. A sensual novelty and a certain disregard for logic are the defining traits of the hang.

Arakawa and Madeline Gins, Screen-Valves, 1985–87; Graphite on paper. 30 x 22.5 in.

During their research, Sunwoo and Lambert came across the artists’ use of the term “eternal gradient,” (from the artists' description of the Bridge.) which Lambert interprets poetically as “the idea of reassembling and never stopping.” This definition carries a sense of the prolific playfulness that characterized Arakawa and Gins’s approach to both work and life. Lambert also suggests that the title connotes structures within the show like “ramps, inclines, the beginning being the end, spectrums, and mathematics.” Such ideas are most apparent in Critical Holder Chart 2 (c. 1991), which shows a hunched silhouette swarmed by mathematical symbols and enveloped by a gray-to-yellow grid. Despite the environment’s attempt to swallow the figure, it steadies itself with an outstretched hand. Recalibrating. Never stopping.

Text by Nolan Boomer.

All photography by Nicholas Knight courtesy Columbia GSAPP © 2018 Estate of Madeline Gins. Reproduced with permission of the Estate of Madeline Gins.

Taken from PIN–UP 24, Spring Summer 2018.

Arakawa and Madeline Gins: Eternal Gradient is on view at Columbia University’s Arthur Ross Architecture Gallery until June 16, 2018.