MENTAL FURNITURE: The Gray Zone Between Functional Sculpture and Nonfunctional Design

In the mid-1980s, the artist and designer Dan Friedman coined the term “mental furniture” as a way to describe his work. A rejection of the Modernist trope “form follows function,” it signaled that, rather than just a basic commodity or utility, his work was a form of art which affected its users in far more ways than the mere fulfillment of physical needs. The same could be said of much of the furniture we surround ourselves with everyday, since it does indeed seem to occupy just as much space in our subconscious as in real life. It represents forms, tropes, and taxonomies that together add up to more than the sum of their parts, becoming social signifiers that carry the cultural DNA of entire civilizations. Present in both our individual and collective memories, furnishings are tools for projection and free association. Which is why artists, time and again, are drawn to their representational value, sometimes independently of the functions they’re meant to perform. And what exactly is function anyway? Surely the representational or the oneiric are functions necessary to the human psyche? On the following pages, PIN–UP presents an array of pieces — some by artists, others by designers, some limited editions, others industrially produced — which occupy that gray zone between functional sculpture and non-functional design. What they all have in common is the ability to transform our everyday environment, whether in the imagination or IRL, into a space of sweet dreams — and sometimes beautiful nightmares.

Rich Mnisi, Nwa-Mulamula, 2018; Leather. Photo by Hayden Phipps. Image courtesy of Southern Guild, Cape Town.

Called Nwa-Mulamula, this seemingly amorphous piece of black leather reveals itself to be a thoughtfully considered chaise longue by South African designer Rich Mnisi. Inspired by Mnisi’s great-grandmother (whose name it bears), the piece has a corporal presence that, despite claims of gender-neutrality, evokes feelings of feminine warmth and resilience. Having never personally met his great-grandmother, Mnisi relied on stories passed on through generations about her guardian power. Nwa-Mulamula is a celebration not only of the culture of oral history but also of Blackness at large.

Jessi Reaves, Rules Around Here (Waterproof Shelf), 2016; Plywood, vinyl, zippers, marker. Image courtesy of Bridget Donahue, New York.

Artist Jessi Reaves creates works that exist in a sphere of their own, between design object and sculpture, constantly destabilizing the ideological precepts at the core of such binaries. Sheathed in a vinyl dress, Rules Around Here personalizes the unlikely object, revealing its hidden sensuality and a hint of morbid kink. The readymade plywood shelf peaks out between the zipper in an embrace not only of DIY materials, but of fetishistic perversion, exhibitionism, and mortality.

Bořek Šípek, Prorok, 1988; Rattan, black cane, ebonized wood. Image courtesy of Studio Bořek Šípek, Bořek Šípek Trust, Prague.

The late Czech designer Bořek Šípek (1949–2016), often considered the Ur-father of the 1980s neo-baroque movement, knew how to imbue his work with theatrical flourish to create heavenly forms. In his crafty hands even a deceptively simple rattan chair develops angelic aspirations thanks to a set of wings woven into the armrests, suggesting the possibility of a celestial escape from our mortal bodies. The Prorok is also available clipped, without wings on the armrests; this simpler version, equally divine, is produced by Italian manufacturer Driade.

Matt Ager, Casual, 2016; Glass, Jesmonite. Image courtesy of Studio Leigh, London.

Artist Matt Ager’s sculpture Casual examines ideas of luxury and status through the image of the coffee table. Playing with clichés of refinement, Ager’s strange appropriation of the Polo Maldini loafers (formed out of acrylic resin) not only communicates a human quality, but a study of quality in general, embodied by the proverbial Italian shoe. An allusion to Narcissus is drawn out from the table’s puddle-shaped glass top, making the object appear more human than originally suspected, gazing back at us.

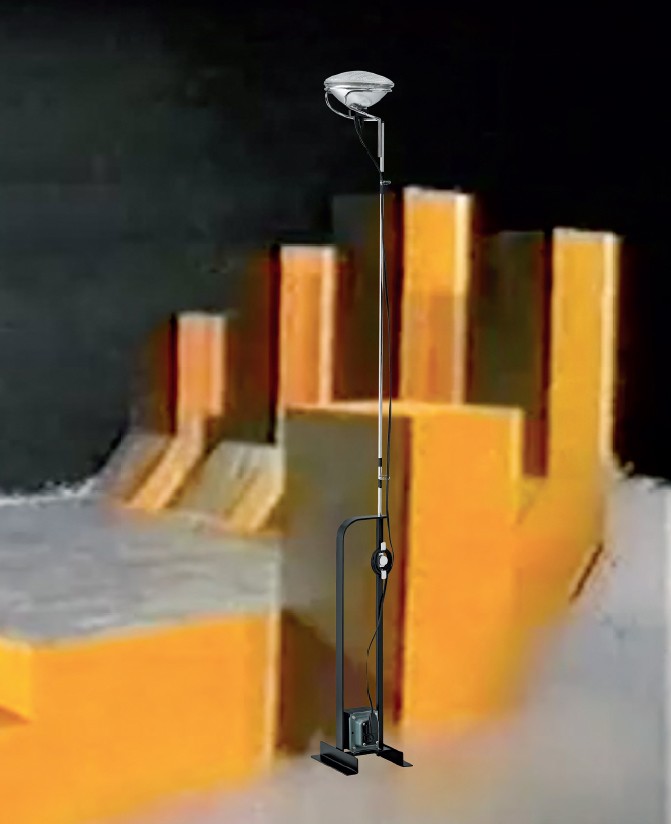

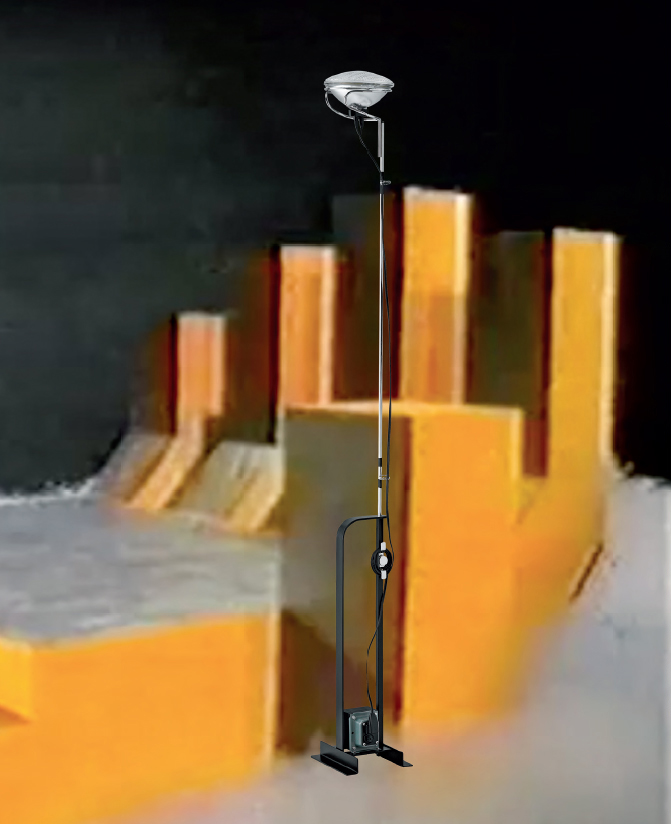

Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni, Toio floor lamp, 1962; Stainless steel, black finish. Available through FLOS.

The oeuvre of Italian design icon Achille Castiglioni (and his brother Pier Giacomo) may not immediately come to mind when thinking of design and spiritual subversion. And yet the late progettista, who would have turned 100 this year, tapped deep into the mental inventory of those living in the modern industrial age. Castiglioni’s ideas for lighting, in particular, provided an endless source of formal experimentation that sometimes pushed the idea of the sophisticated readymade into the realm of the absurd. The fact that today most of the Castiglionis’ light sources are still successfully being sold by FLOS stands testament to the enduring legacy of their preposterousness.

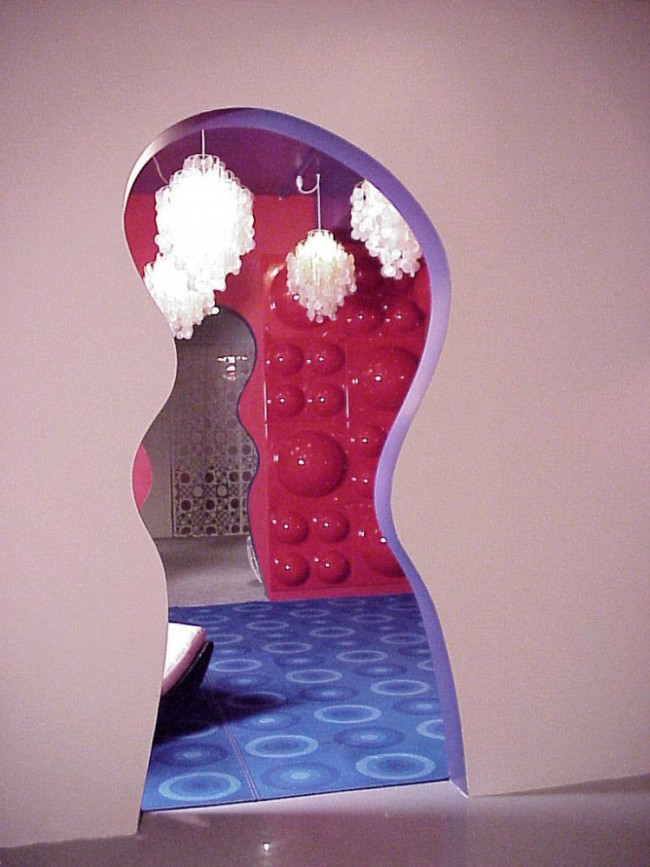

Dora Budor, YEAR WITHOUT SUMMER (PANTON’S DIVERSION), 2017; Repurposed Vernor Panton models, ash. Image courtesy of the artist.

Artist Dora Budor’s YEAR WITHOUT SUMMER (PANTON’S DIVERSION), an installation at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark, makes a nightmarish return to the Pop era of design, repurposing Verner Panton’s Wohnlandschaft from 1965. From the gallery ceiling, soot precipitates onto the lounge chairs, smothering the colorful optimism of the original pieces. Budor’s intervention suggests deterioration and decay in the domestic climate. The immolation of a surrounding architecture may be triggered by objects ready to combust.

Chris Schanck, Gold 900 table, 2018; Wood, burlap, polystyrene, resin, aluminum. Photographed for PIN–UP by Josep Fonti at Friedman Benda, New York.

Despite being made from humble materials like aluminum foil, wood, and Styrofoam, Detroit-based designer Chris Schanck’s work often exudes an otherworldly quality. The Gold 900 table, for example, encapsulates mythological brawn, like an Atlas weighed down and deeply humbled by a flattened sky. The combination of Schanck’s conception puts a limit on limitlessness, or rather compartmentalizes the vastness of the universe outside the home — like the theory of a big domestic bang.

Paul Kopkau, Barcelona, 2016; Folding table parts, wood, polyester velvet, upholstery foam, thread, staples. Image courtesy of Company Gallery, New York.

Evocative of the essential instrument in Freudian psychoanalysis, Paul Kopkau’s Barcelona appears like a sort of utilitarian fever dream of a couch. If the cushy original and its many successors rang in the medicalization of comfort in the 20th century, Kopkau’s sculpture has the opposite effect: with its precarious construction — a DIY mix of elements borrowed from common folding furniture upholstered in faux-velvet — it is more anxiety-inducing than comforting. This communicative reversal is only further emphasized by the fact that the piece shares its name and dimensions with Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s iconic Barcelona® Couch from 1930, an object of aesthetic promise and aspirational tyranny.

Anna Uddenberg, Twin Generators and Upgraded Tender, 2017; Styrofoam, acrylic resin, fiberglass, polyurethane foam, HDF, automobile-interior elements, synthetic leather, chromed table parts, carpet, vinyl-foam stripes, hiking backpacks, aluminum climbing carabiners, climbing gear, belt, LED lights, mesh fabric. Photo by Gunter Lepkowski. Image courtesy of the artist and Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin.

Contorting commercially manufactured objects, Berlin-based artist Anna Uddenberg creates pieces that render everyday design elements into Frankenstein’s monsters of unnerving uselessness. In her piece Twin generators and Upgraded Tender, a sense of colorless, clinical purity — as found at a boutique dentist’s or a luxury beauty parlor — stands in stark contrast to its material abundance, which includes everything from car parts and bathmats to climbing gear and LEDs. The result is a piece of ”furniture” shrouded in practical enigma, embodying a hollow promise of exclusivity.

Kirsten Wentrcek and Andrew Zebulon, 705 Chair, 2017; Vietnamese natural rubber, Corian®. Image courtesy of the artists.

Formerly known as Wintercheck Factory, Brooklyn-based designers Kristen Wentrcek and Andrew Zebulon create objects that find solace in abstraction. Their 705 Bench series is a simple construction made from a Corian® base topped by natural rubber. The base acts like a plinth, displaying a caramel or toffee like cushion, playfully blending minimalist precision à la Judd with a Willie Wonka-style flare for fantasy — a Modernist dream of a bittersweet tooth that refuses to be brushed.

Giorgetti, Progetti Fashion 33230, 2017; Beech wood, sheepskin. Available through Giorgetti.

Ever since it was introduced in 1987, the Progetti armchair by the Italian design group Giorgetti has enchanted with its cocky, upright stature and signature curved armrests. Shaped like cane handles, the latter seem more wielded by than affixed to the chair, calling to mind umbrella-carrying fantasy characters such as Charlie Chaplin, Mary Poppins, or Pan Tau (the much-loved silent wizard from Czech children’s television). In 2017, in celebration of Progetti’s 30-year anniversary, Giorgetti playfully dressed the four-legged pleaser in a sheepskin coat, so that it gambols even further into our childlike subconscious.

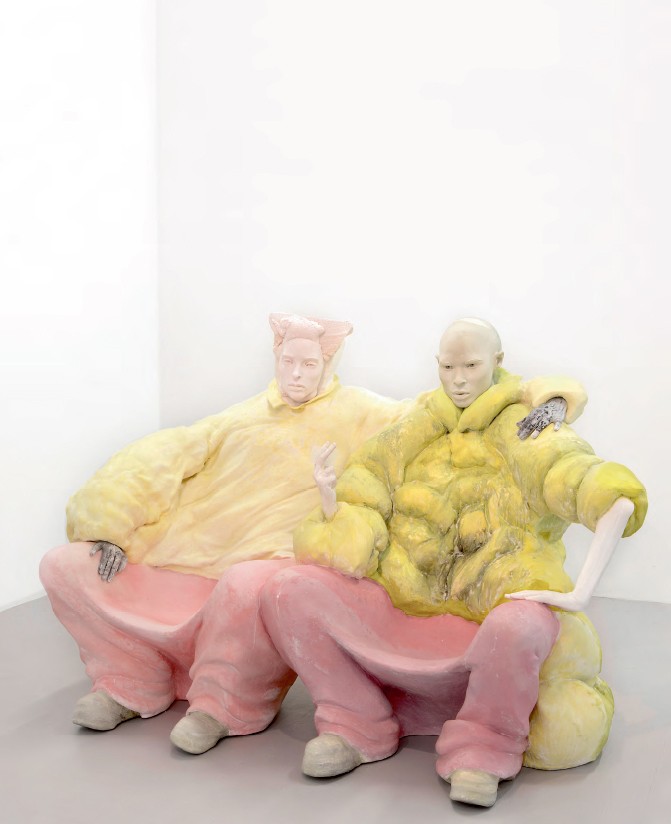

Casja Von Zeipel, Butch Bench, 2017; Styrofoam, epoxy, fiberglass, aqua resin, foam spray, metal, MDF, pigment, wax. Image courtesy of Company Gallery.

Artist Cajsa von Zeipel’s Butch Bench stages a sororal, slightly coercive scene of beckoning. While most benches offer their seat as invitation, the Butch Bench seeks to take control of your posterior, ordering it to squeeze itself into either of the less-than-comfortable curves of the sculpture’s pair of laps. It’s a figurative abuse of power that comes as some surprise, especially to those who — naïvely or not — refuse to contest the stipulations of control believed to be intrinsic to gender, sex, and money.

Elias Hansen, There Ain’t Nothing a Person Can’t Learn About Themselves From the Open Road, 2017; Glass, steel, hardware, CFL bulbs. Image courtesy of Halsey McKay Gallery, New York.

Suspended from the ceiling, artist Elias Hansen’s There Ain’t Nothing a Person Can’t Learn About Themselves From the Open Road seems to parody its status as a chandelier. Constructed out of what appears to be a mixture of beakers, bongs, and Heineken bottles, mixed with energy-saving fluorescent light bulbs and hand-blown glass, Hansen’s overhead lamp casts a mysterious glow. A purely aesthetic, non-functional beacon, the skeletal form lingers above, like a disco ball in club for the undead.

Ian Stell, Cricket Cage, 2017; Aquatinted aluminum, stainless steel. Photo by Clemens Kois. Image courtesy of Patrick Parrish Gallery, New York.

Designer Ian Stell’s Cricket Cage chair harks back to an ancient tradition of keeping orthoptera as pets and using them for domestic entertainment. Stell, who excels at kinetic design, combines in this chair the ceremonial aspects of opening and closing: lifting and lowering the three separate elements of the chair is a performance that oscillates between notions of freedom and captivity, sometimes even life and death. The jump in scale only underscores this exercise of power, imposing a sense of potency paired with dread on whoever decides to sit down.

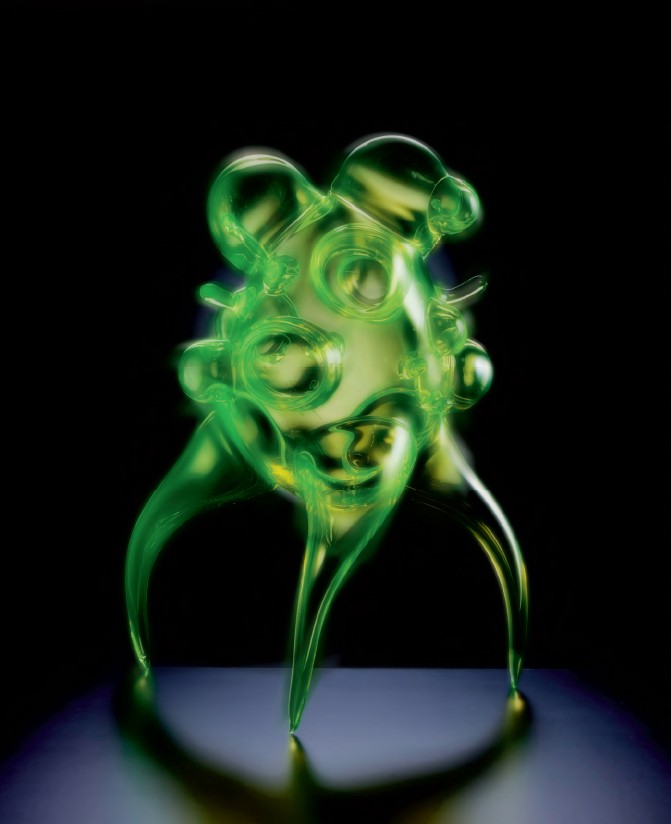

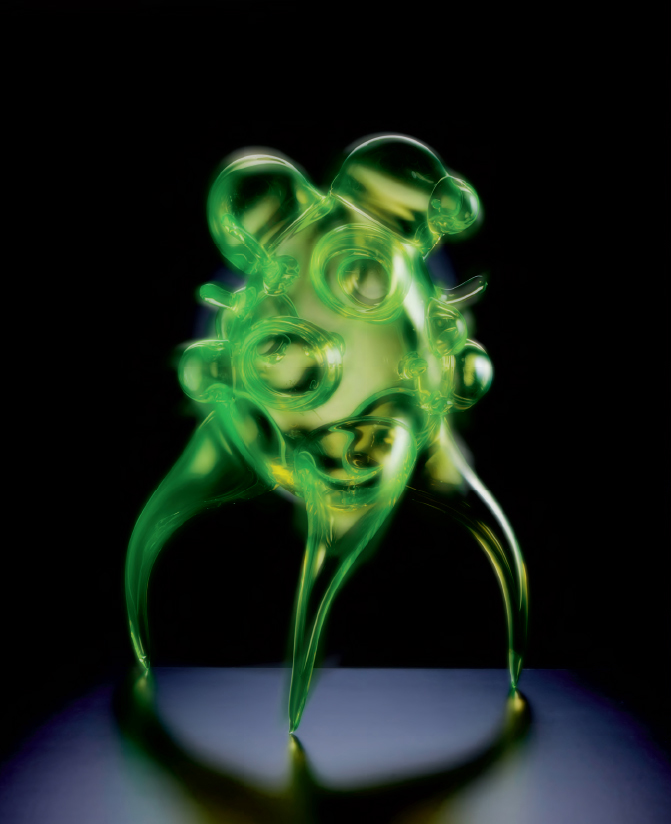

René Roubíček, The Martian, 2018; Hand-blown uranium glass. Available through Lasvit.

Nonagenarian Czech glass artist René Roubíček creates futuristic, sci-fi influenced glassware that seems to have been blown out of deep space. With the unapologetically functionless Martian (2018), Roubíček seems to introduce life from another planet into the domestic realm. Its translucent green materiality — suggestive of an alien dermis — is achieved by adding a small dose of uranium during the glass-making process (undertaken by the Czech glassmaker Lasvit). The weakly radioactive toxic metal lends an additional notion of underlying danger to an already otherworldly object.

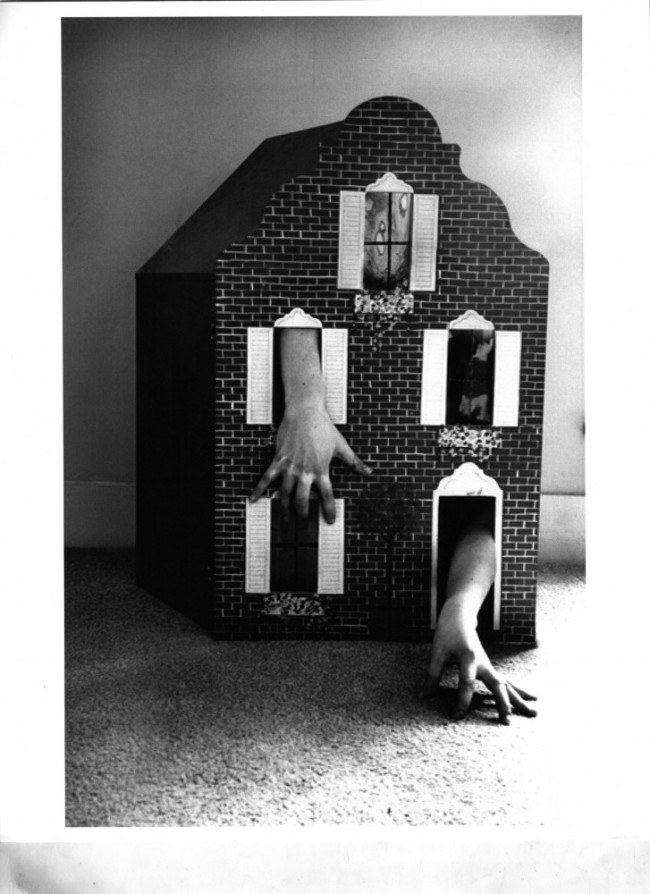

Hannah Levy, Untitled, 2017; Nickel-plated steel, silicone. Image courtesy of the artist.

Artist Hannah Levy often uses the term “design purgatory” to describe the sculptures she produces (see also here). Nodding towards Meret Oppenheim’s Surrealist Traccia table from 1939, her piece Untitled (2017) seems to be clawing itself out of functionality into a realm of dreamlike, sculptural animation, a hybrid creature on the brink of emancipation. The slender, slightly sensual silicon body struts forward on steel talons, inviting us to consider the desire inherent in inanimate things which have become objectified by their use.

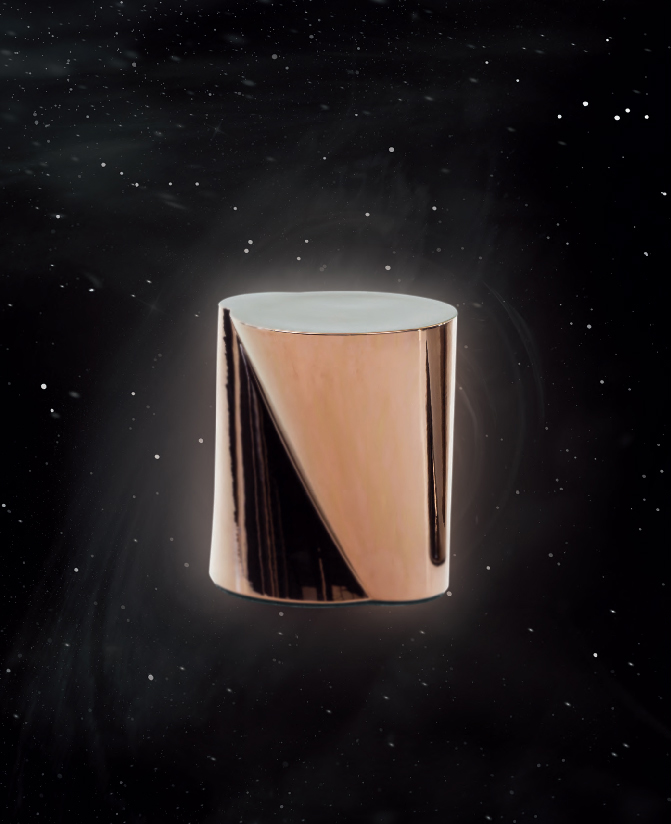

Christophe Delcourt, NOOR end table, 2017; Truncated cones, bronze, platinum finish. Available through Minotti.

According to some schools of dream interpretation, the tree trunk is a symbol of life, the passing of time, and of the memory it carries. Christophe Delcourt’s metallic NOOR end table for Minotti borrows its configuration from the pregnant shape of our foliate friends, giving the impression of being carefully cut down from a magic forest and transported to our domestic confines. Combining minimalist figurative sensibilities with an ornate finish, NOOR is a totem and mythological emblem of the delicateness of life.

Sam Stewart, Untitled (chair), 2017; Maple, beech, vinyl, leather. Photo by Lauren Coleman. Image courtesy of the artist and Fort Gansevoort, New York.

Continuing the theme of defeatism, hybridity, and precious materials, Sam Stewart’s stick chairs have been netted into the domestic realm with their arborous backs upholstered in what the artist refers to as “body bags.” By putting the tradition of hickory-twig furniture (from the artist’s home state of North Carolina) on display through transparent vinyl slipcovers, Stewart offers an absurdist nature morte that mocks, mourns, and memorializes common tropes of Americana, challenging both ideas of status and the illusion of continual use.

Soft Baroque, Hard Round, 2017; Walnut wood. Photo by Clemens Kois. Image courtesy of Patrick Parrish Gallery, New York.

London-based design duo Soft Baroque’s Hard Round shelf mimes the shape of a multi-tiered wooden plant stand, a furniture typology popular in households of different classes in many cultures around the world. Yet Soft Baroque deviously introduce a decidedly un-organic element: the “hard round” brush tool from Adobe Photoshop®, which was used to derive the shelf’s specific form. The result is a few digitally driven worm-like shapes that carelessly crawl right through our subconscious, infesting any collective nostalgia we may have had for decoratively domesticated vegetation.

Mary Little, Liz, 1994; Painted steel frame, carved polyurethane foam, wool, silk. Image courtesy of the artist.

Visually akin to a well-groomed show dog or a grouping of hot-air balloons, sculptor Mary Little’s furniture from the mid-1990s seems to mimic reality’s campier, uncannier figurations. Originally inspired by the hats in 16th-century Hans Holbein paintings, Liz has a lumpy, quadrupedal geometric dimensionality and a pin-like figuration in polyurethane foam adorned with wool and iridescent silk. The result is a piece that juggles shape and texture with our perception of form, wearing its cartoonish royalty on its proverbial sleeve.

Zhipeng Tan, 33 Step Bar Chair, 2016; Polished brass. Image courtesy of Gallery All, Beijing/Los Angeles.

Imbuing the heritage process of lost-wax casting with naturalistic figuration, Zhipeng Tan’s 33 Step Bar Chair combines the industrial with the organic, a testament to the designer’s ongoing fascination with abstracting basic natural elements. The 33 Step Bar Chair takes this process one step further, aligning itself with the kind of Surrealist human corporeality Salvador Dalí was wont to explore. But unlike Dalí and his contemporaries, Tan prefers reality to fantasy, and thus warps life into objects that were previously only part of the imaginary, triggering a kind of meta-perception in the process.

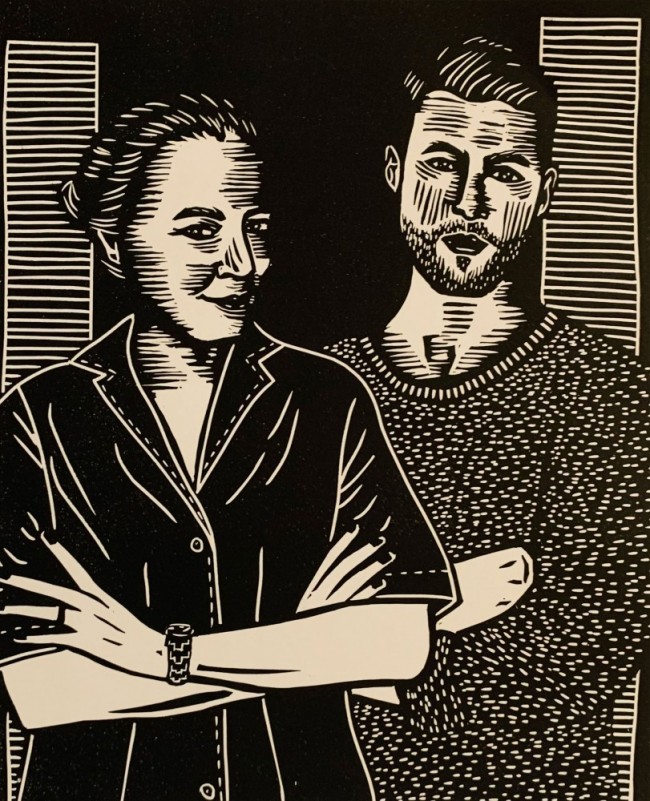

Design A+B, Mate, 2013; Steel, epoxy. Photographed by Josep Fonti for PIN–UP. Available through Living Divani.

With Mate, the Italian duo Design A+B — Annalisa Dominoni and Benedetto Quaquaro — created a seat in the house that is perhaps best kept empty. Produced by Living Divani, Mate seems to invert function and form, offering a helping hand for support and relief. Borrowing from the narrative construction of the likes of Robert Wilson and Charles Rennie Mackintosh, it seems to tell the story of an in-house companion who’s perfected the combination of casual servility and total discretion.

Andy Robertson, The What Goes Round Comes Around Chair, 2017; Stained plywood, vintage cushions, leather bolster, duck-pin bowling ball. Photo by Michael Jon Radziewicz. Image courtesy of the artist.

Andy Robertson’s The What Goes Round Comes Around Chair takes its cues from Thomas Lee’s 1903 Westport Chair — said by Westport locals to be the progenitor of the more common Adirondack chair — proving that inspiration really does cycle around. The loud vertical stripes on the vintage cushions approximate very earthly design aspects enveloped by the architecture of the chair, which itself looks fit for rustic lounging in deep-space travel. A sensation only added to by the blue globe which sits on the armrests. A slight shift in our perception occurs: sit back, in complete control, while the world revolves around you.

Katie Stout, Bench in Three Marbles, 2017; Yellow Negrais marble, Negro Marquina marble, Portuguese travertine. Image courtesy of R & Company, New York.

Katie Stout’s Bench in Three Marbles teeters between elegant materiality and primitive figuration, providing an aesthetically ambivalent space to rest. The polished marbles’ rich, luxurious hues do not confront the way the whole ensemble has seemingly been toppled together, like menhirs haphazardly put to use at a billionaire’s children’s birthday function. Instead of seeking conflict in its heft and levity, the piece celebrates its various impressions of ornateness in organic form.

Curated by Jack Chiles and Felix Burrichter.

Text by Marc Matchak.