Jean-Jacques Lequeu, Fantasy Builder or Parafictional hoax?

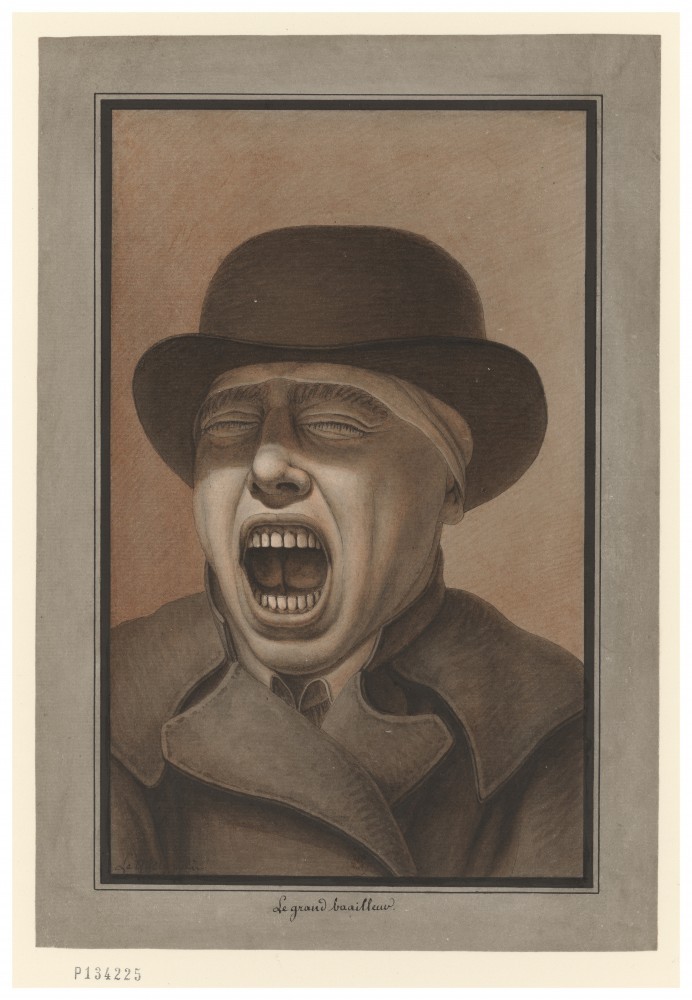

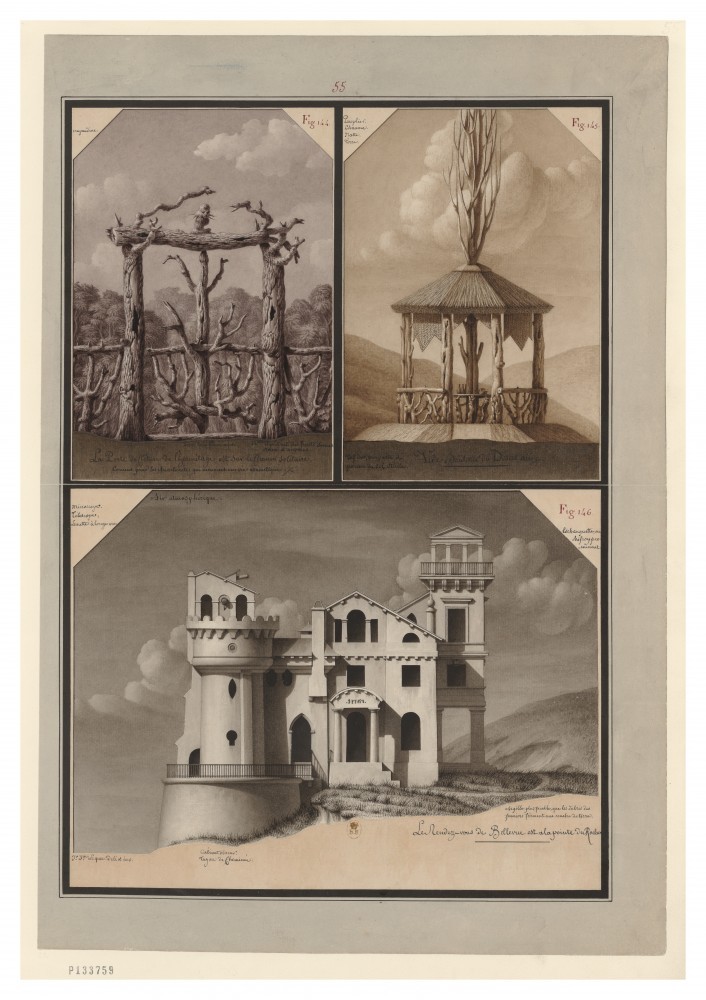

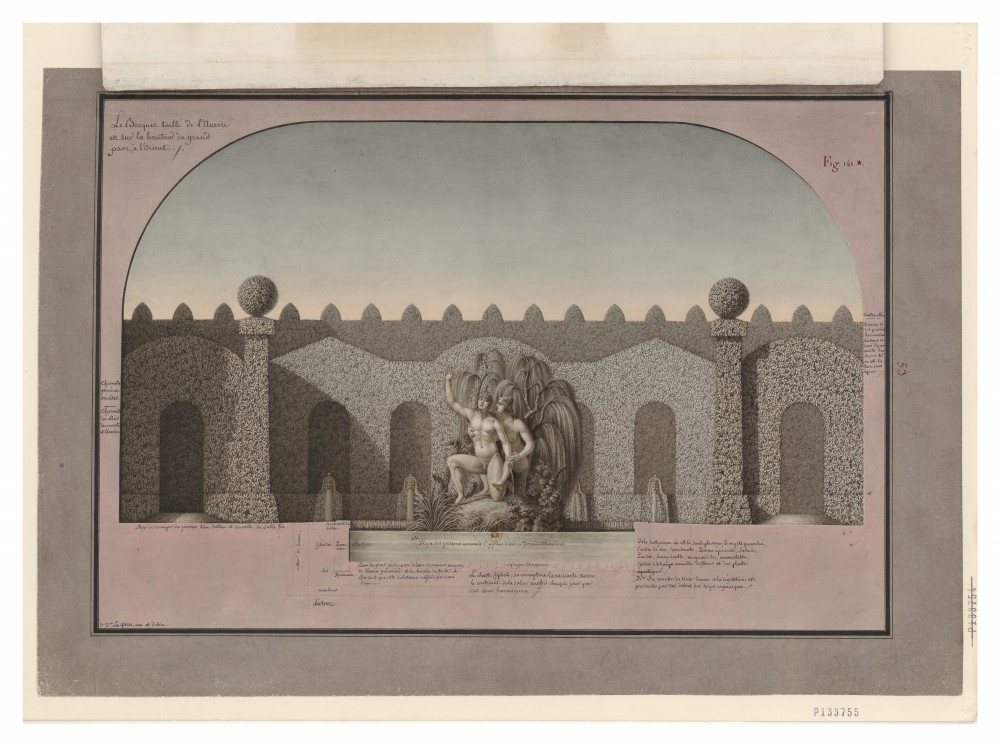

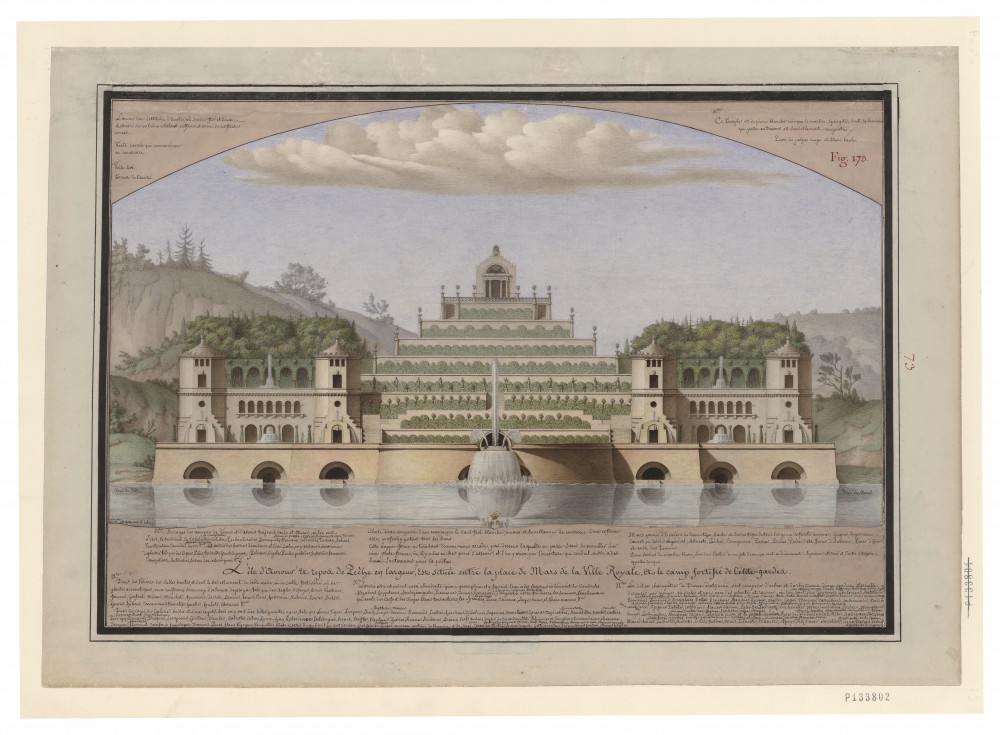

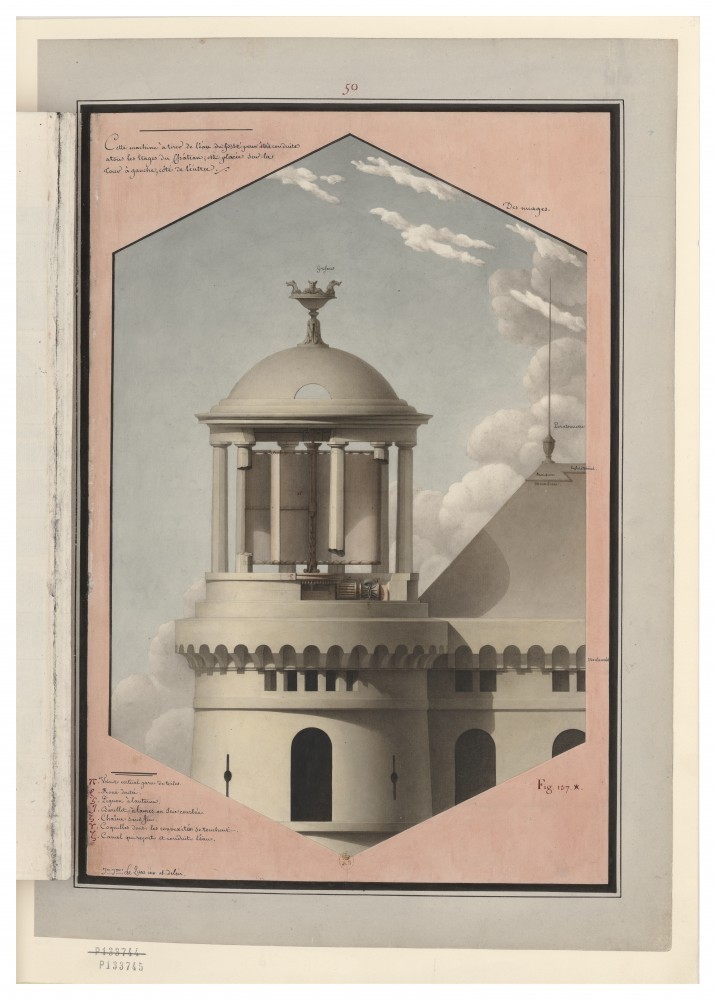

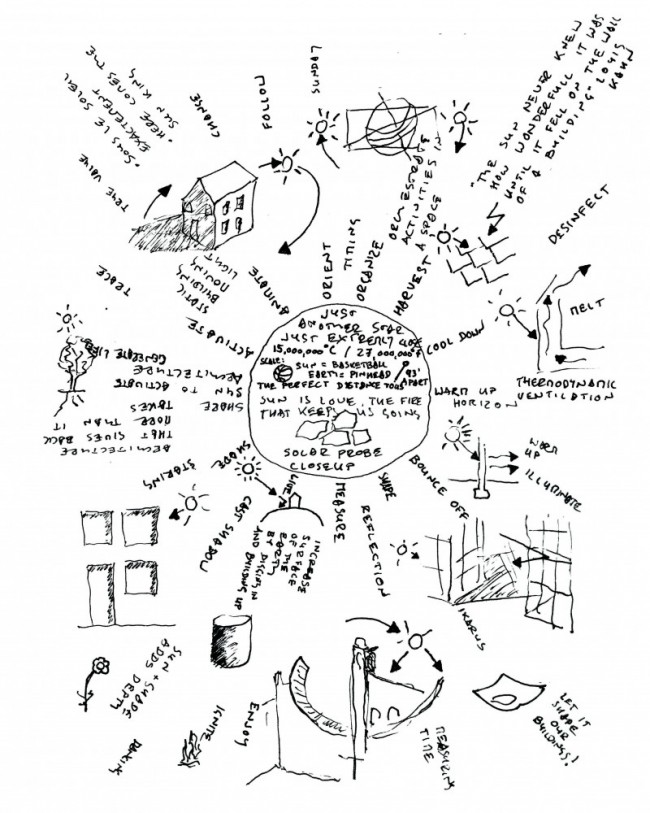

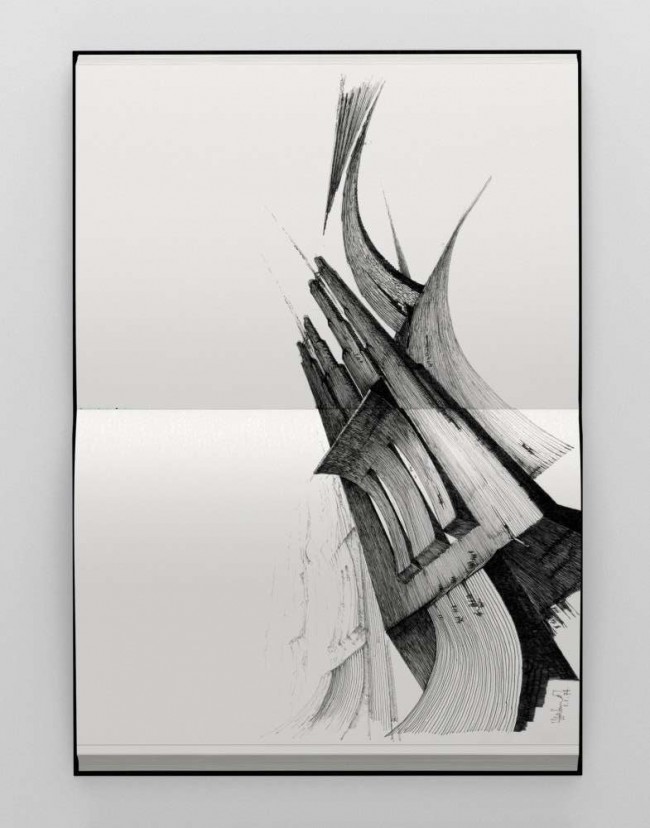

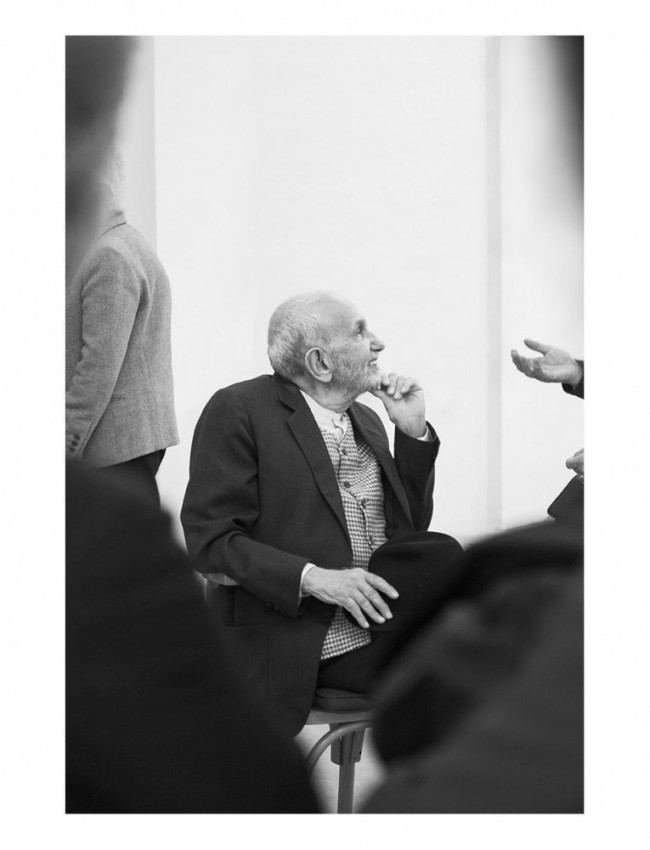

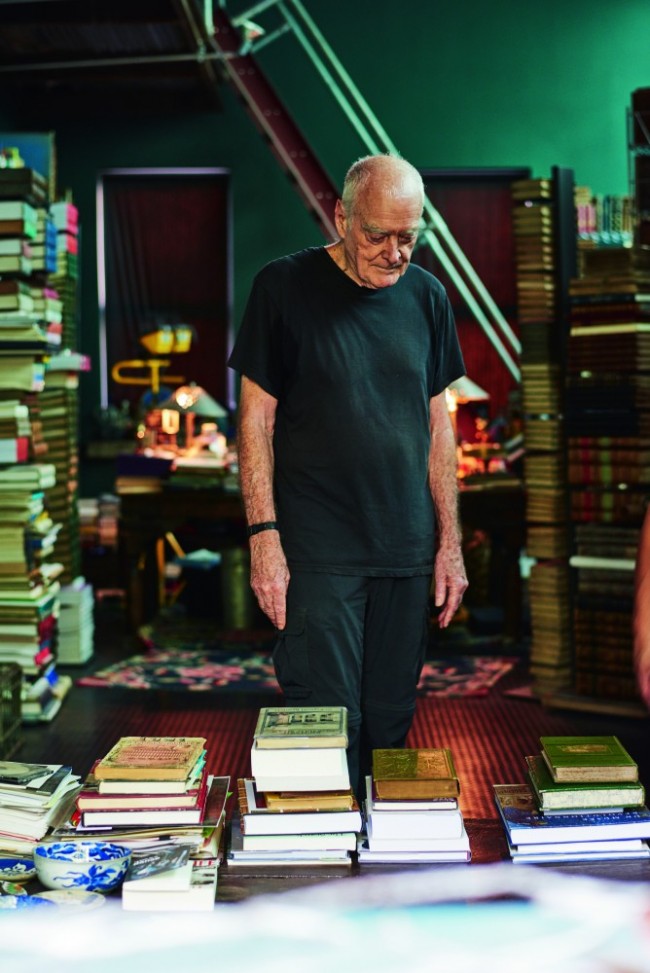

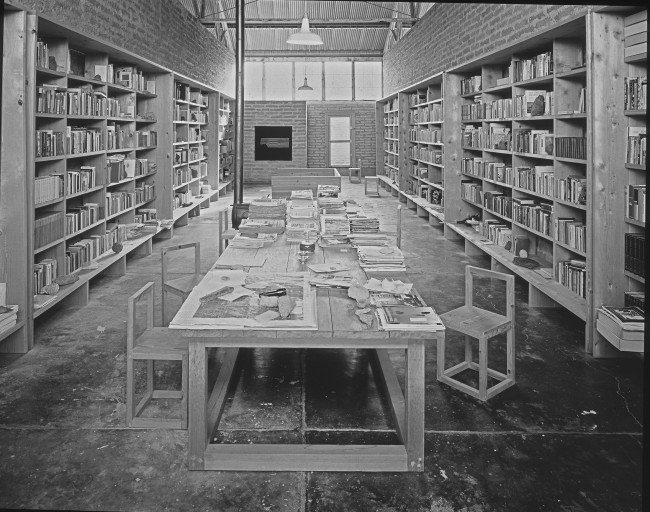

Imagine a series of 770 exquisitely rendered drawings long slumbering in the hallowed halls of France’s Bibliothèque Nationale. Produced in Enlightenment France, before and after the Revolution, the majority are architectural projects, details, and surveys, but they bear a distinctly uncanny-valley relationship to the usual iconography of that time and place. A Monument to the Exercise of the People’s Sovereignty piles up several ziggurats, a sphere resembling a hot-air balloon, a tempietto, and a pair of Corinthian-column chimneys; a design for an imperial palace decks out Gabriel’s Versailles in an eclectic collection of references, producing the most exotic yet literal effect. And then there’s the erotica, which includes studies of female genitalia rendered with the precision of crisply carved stone, a faun’s penis deformed by paraphimosis, and an anticlerical depiction of a doll-like nun revealing her breasts above the inscription “And we too shall be mothers, for...” Welcome to the weird and disconcerting world of Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826), “builder of fantasies,” as the catalogue of a recent exhibition on his work would have it, or simply “architectural draftsman” as historian Philippe Duboÿ’s book-length essay on the Lequeu phenomenon modestly, and perhaps more accurately, puts it.

Jean-Jacques Lequeu, Et nous aussi nous serons meres (1794).

The sumptuously illustrated catalogue, produced to accompany 138 of Lequeu’s drawings displayed at Paris’s Petit Palais (the show will travel to New York’s Morgan Library next spring), features nine scholarly essays that attempt to demystify a lowly draftsman who, though he built almost nothing, long dreamt of becoming an important architect. Setting him in his time and place, pointing out parallels and precedents, the authors nonetheless fail to overcome the major obstacle — what we don’t know about Lequeu far exceeds what we do. This vacuum leaves the field wide open for all sorts of interpretations of his often impenetrable oeuvre, among which the most far-fetched must surely be Duboÿ’s.

Jean Jacques Lequeu: Dessinateur en architecture tells the tale of Duboÿ’s early academic career in Venice and Paris — rubbing shoulders with such intellectual luminaries as Manfredo Tafuri, Carlo Scarpa, Roland Barthes, and Michel Foucault — while researching Lequeu for his thesis and afterwards for publication. The longer he worked on the drawings, the more Duboÿ became convinced they had been tampered with, until, following a series of odd encounters he came to the extraordinary conclusion that, in its current state, the collection is nothing less than a “rectified readymade,” an elaborate hoax orchestrated by — you guessed it! — Marcel Duchamp.

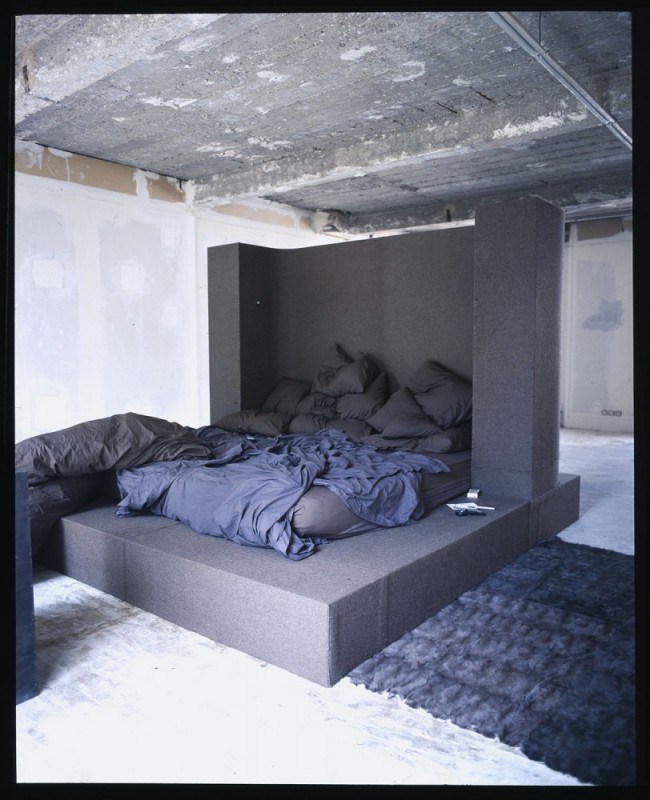

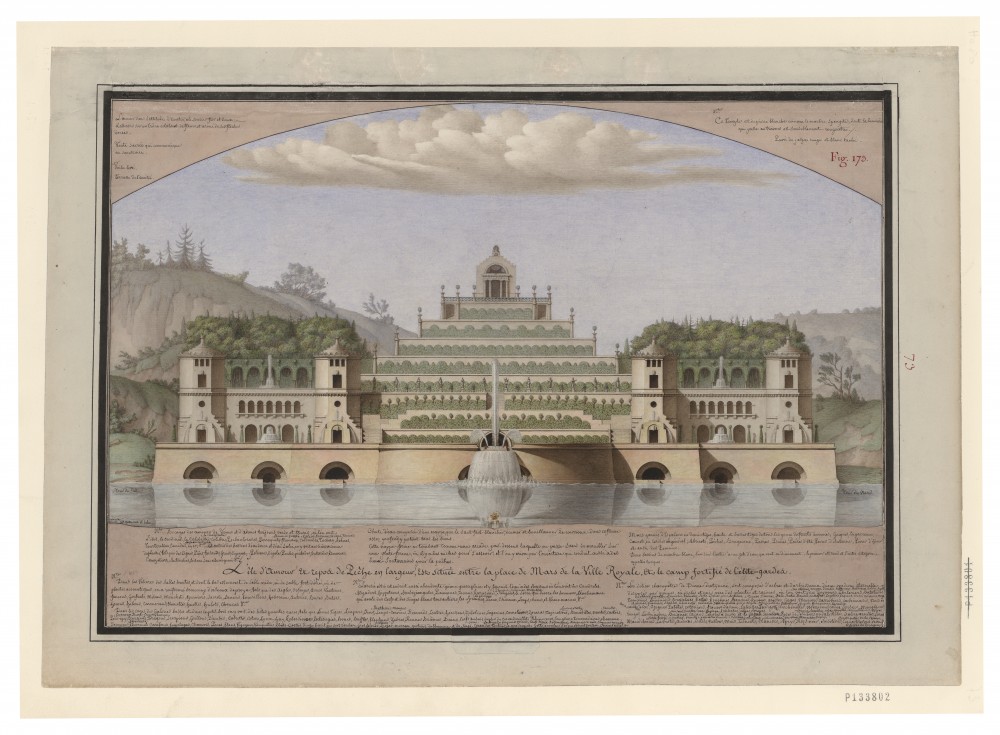

Jean-Jacques Lequeu, L'Île d'amour et repos de pêche.

Key to this interpretation is View of the Felix Valleys Fountain, an image showing a typically libertine scene of female bathers in a pool surrounded by a hedge, from behind which a Peeping Tom is savoring their naked ablutions. But look closely and you’ll notice that the sunlight falling on the right-hand side of the hedge seems to trace out a profile — and for Duboÿ that profile is none other than Duchamp’s. One can’t help wondering if Duboÿ’s “investigation” isn’t itself an elaborate parafiction. As Robin Middleton put it in his 1986 preface, “Duboÿ has compounded the mystery, and deliberately so ... (He) resolves nothing. He probes. He teases and tantalizes. He plays a fiendish game.” It’s left to the intrepid reader to follow the punning detective trail, where everything has a double if not triple meaning, in a four-dimensional ballet of Duchampian chess moves that leads us from Fourier and Brillat-Savarin all the way to — wait for it! — Le Corbusier.

Read together, these two books form a rich introduction to the tantalizing Lequeu, whose architect persona was, for Duboÿ, “his most interesting literary creation.” From Damien Hirst to Miles Gertler, parafictions are all the rage these days, and in Lequeu’s triumphant naivety, we find a mulishly manic master.

Text by Andrew Ayers.

Images courtesy Éditions Norma.

The exhibition Jean-Jacques Lequeu: Visionary Architect. Drawings from the Bibliothèque nationale de France is on view at the Morgan Library & Museum until May 10, 2020.