BOOK CLUB: Beatrice Galilee’s Anthology Of Radical Architecture

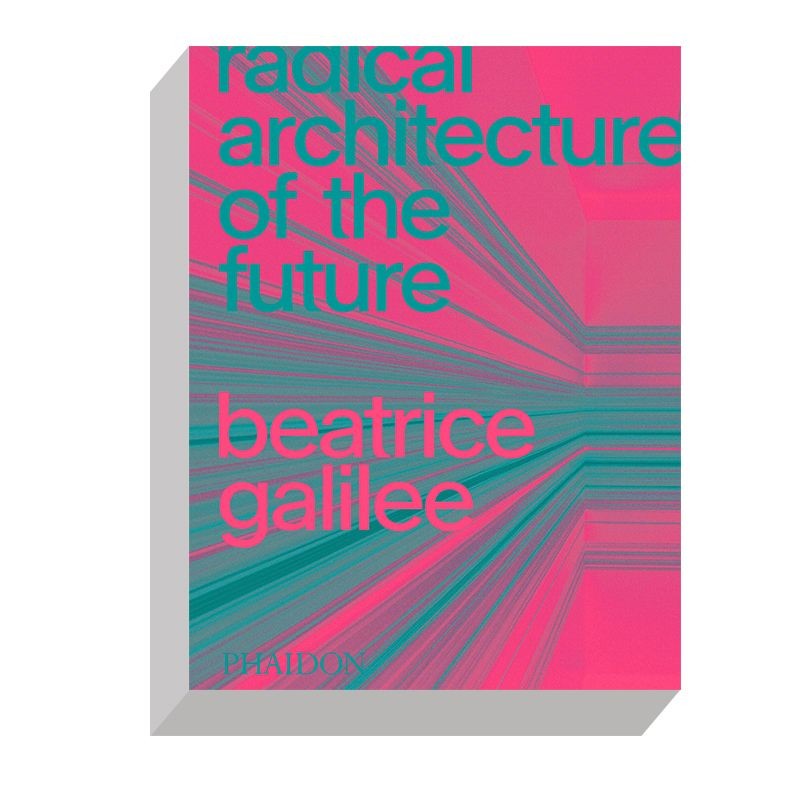

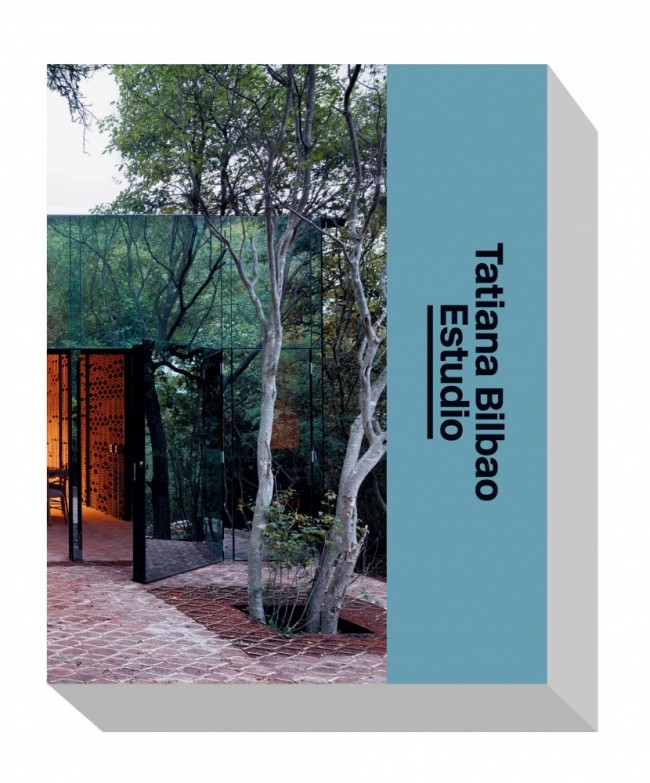

Curator and self-described “organizer of things” Beatrice Galilee’s new book Radical Architecture of the Future (Phaidon, 2021) is a condensed encyclopedia of Galilee’s previous architecture summits “The World Around,” “Earth Day,” and “A Year of Architecture in a Day.” Her book challenges contemporary architectural discourse in five chapters — visionaries, insiders, radicals, breakthroughs, and masterminds — dedicated to radical yet realized projects from the last decade that prove architecture can thrive across disciplines like bio design, AI systems, disaster relief, adaptive reuse, and grassroots initiatives.

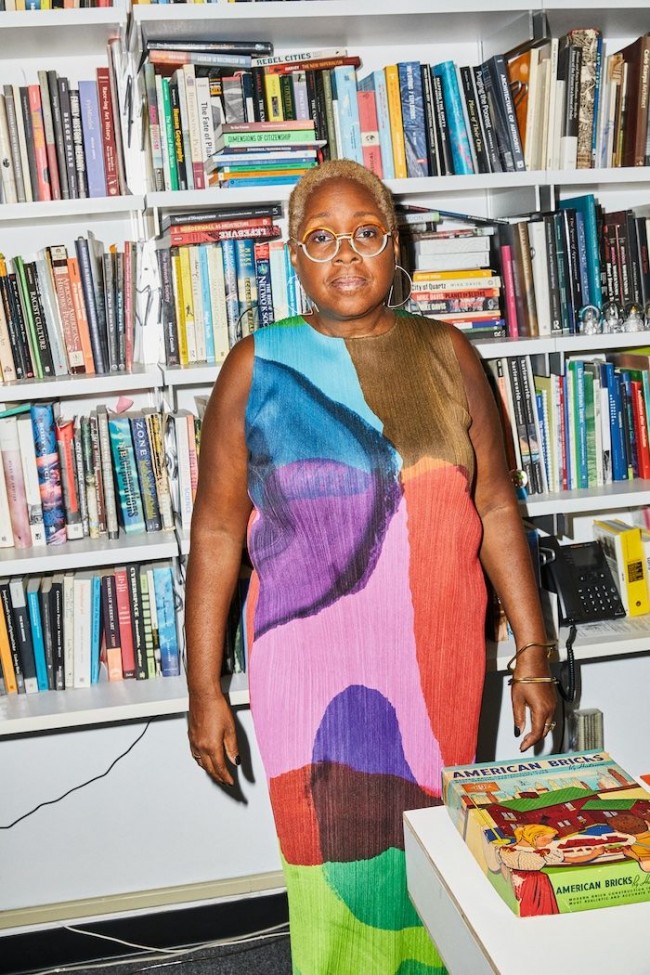

Among the “visionaries” Galilee examines is EVA Studio, whose projects include a community-oriented multi-functional public space in Port-au-Prince, Tapis Rouge (2016), a park built with the participation of local residents featuring an open-air amphitheater, water pump, exercise equipment, and solar-powered lights. Also in this chapter Galilee spotlights “Marching On: The Politics of Performance” (2017) a research project and exhibition by Bryony Roberts and Mabel O. Wilson featuring a performance by the Marching Cobras, a Harlem-based drumline and dance team. Roberts and Wilson put this performance in context of a legacy of African-American demonstrations and bodies taking over public space, spanning both cultural expression and political resistance.

-

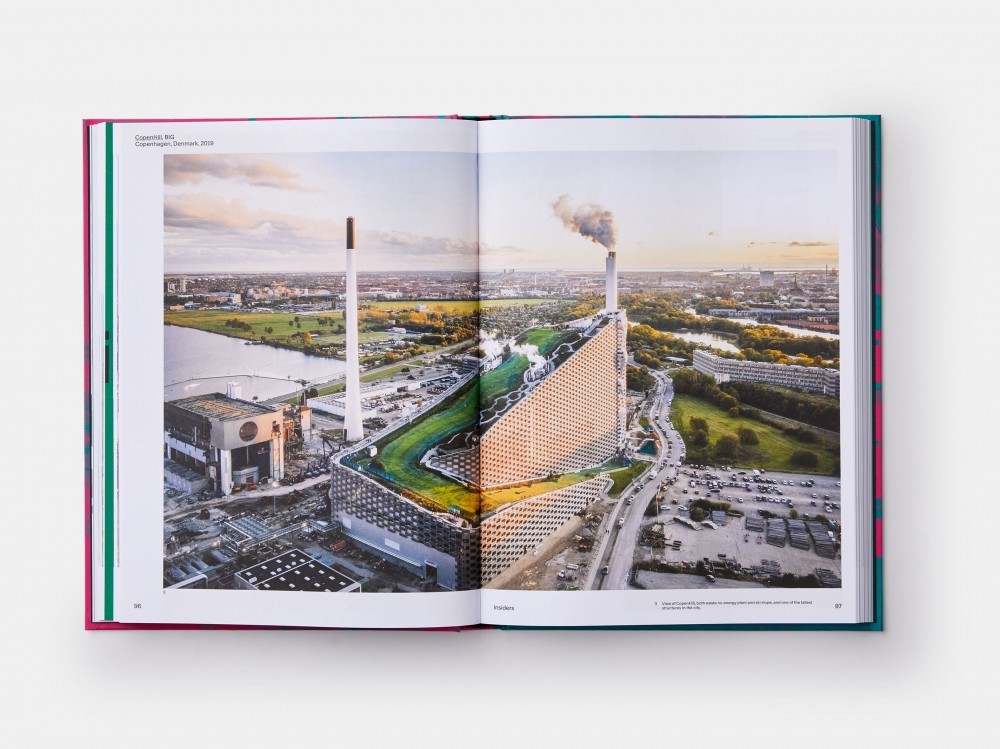

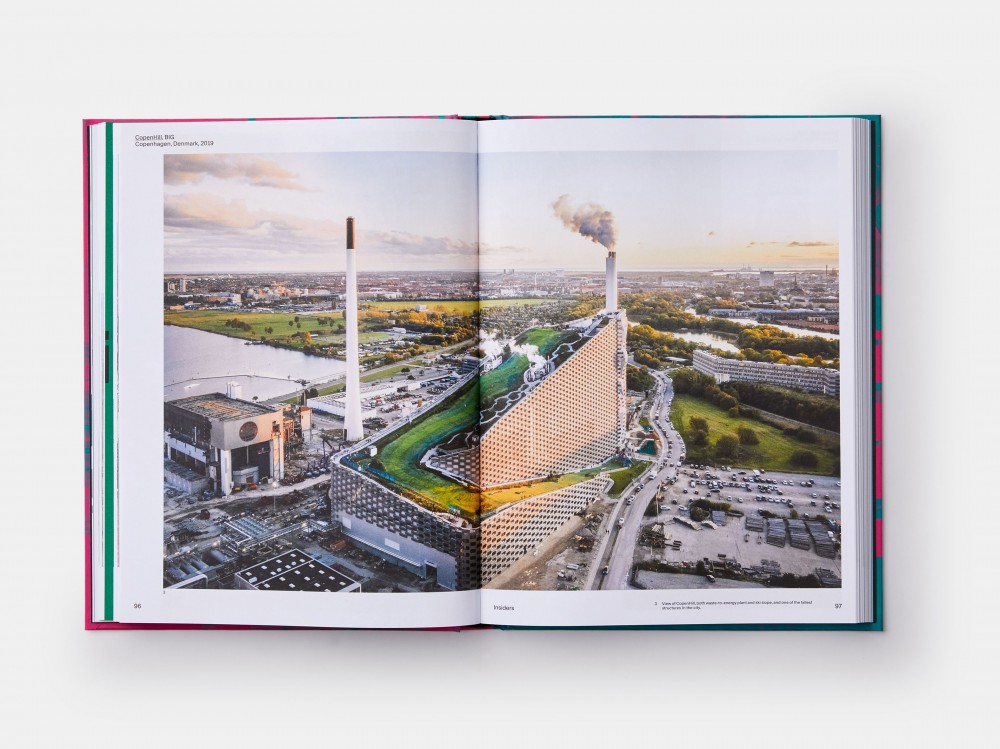

Pages 96 and 97 feature CopenHill a waste-to-energy plant and sports facility in Copenhagen designed by Bjarke Ingels Group in Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019. © Rasmus Hjortshoj.

-

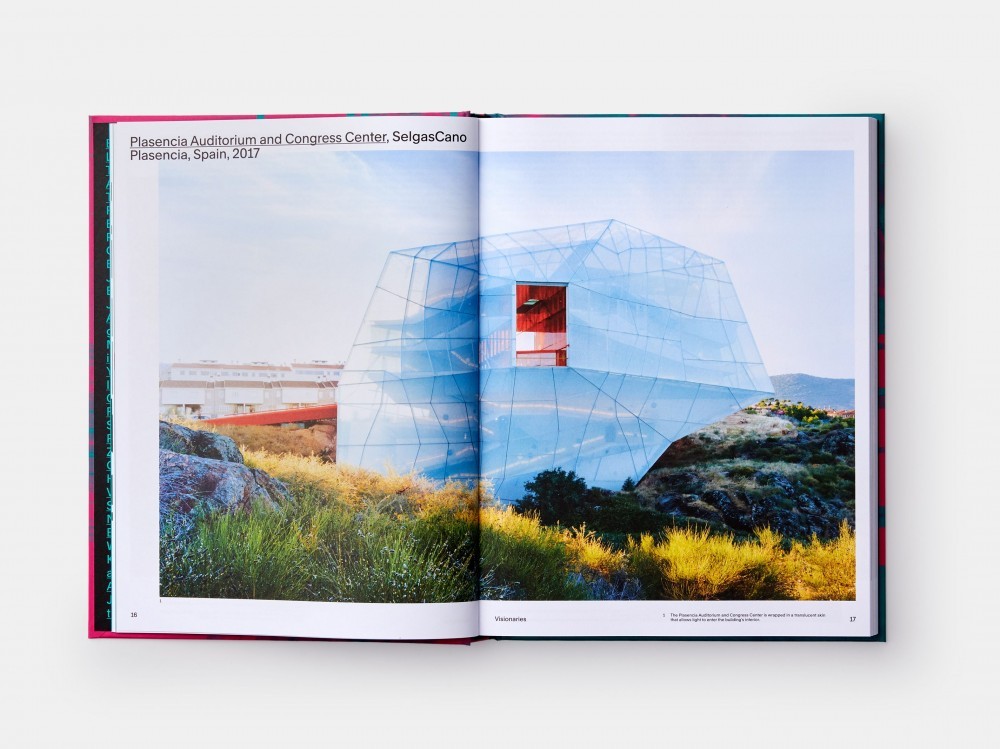

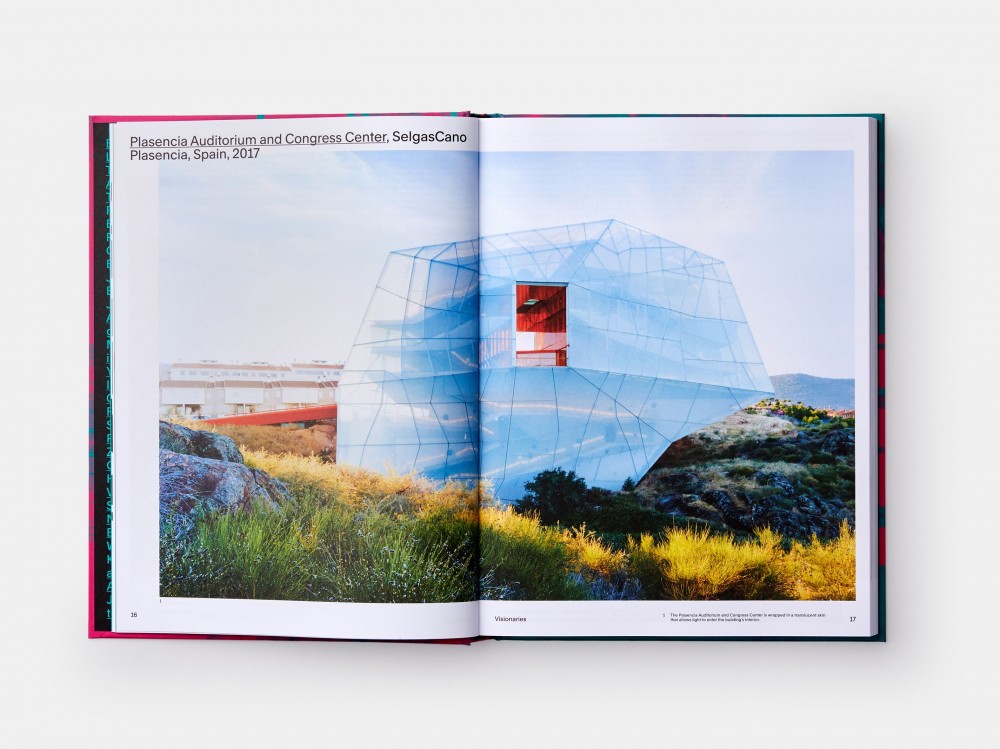

Pages 16 and 17 feature Plasencia Auditorium and Congress Center, Selgas Cano, Plasencia, Spain, 2017. © Iwan Baan.

-

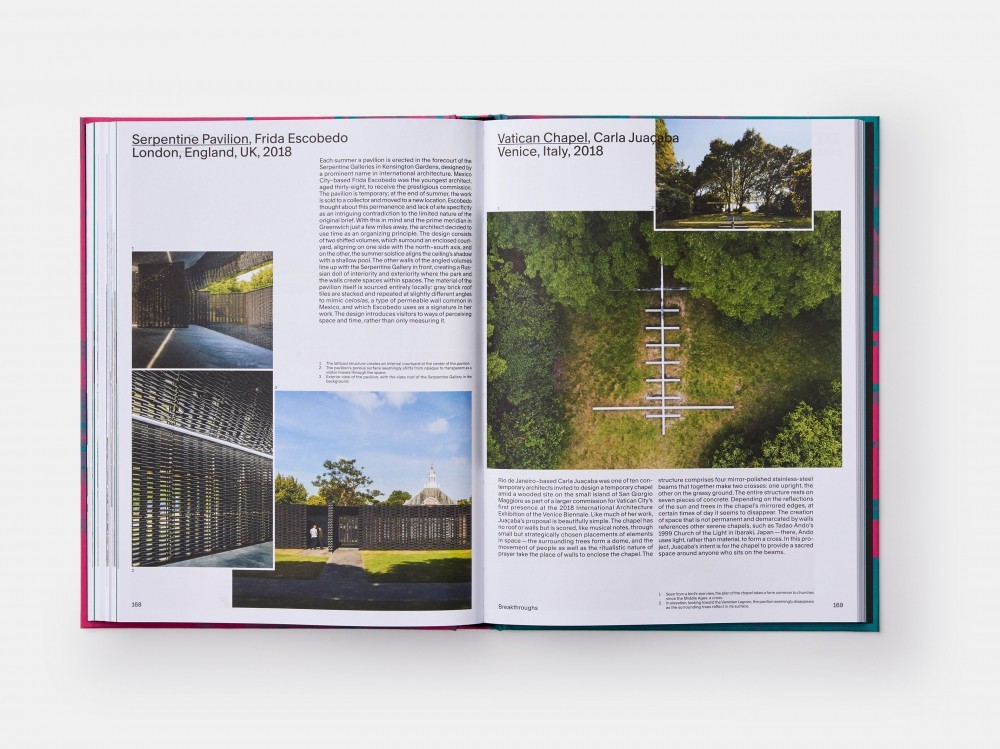

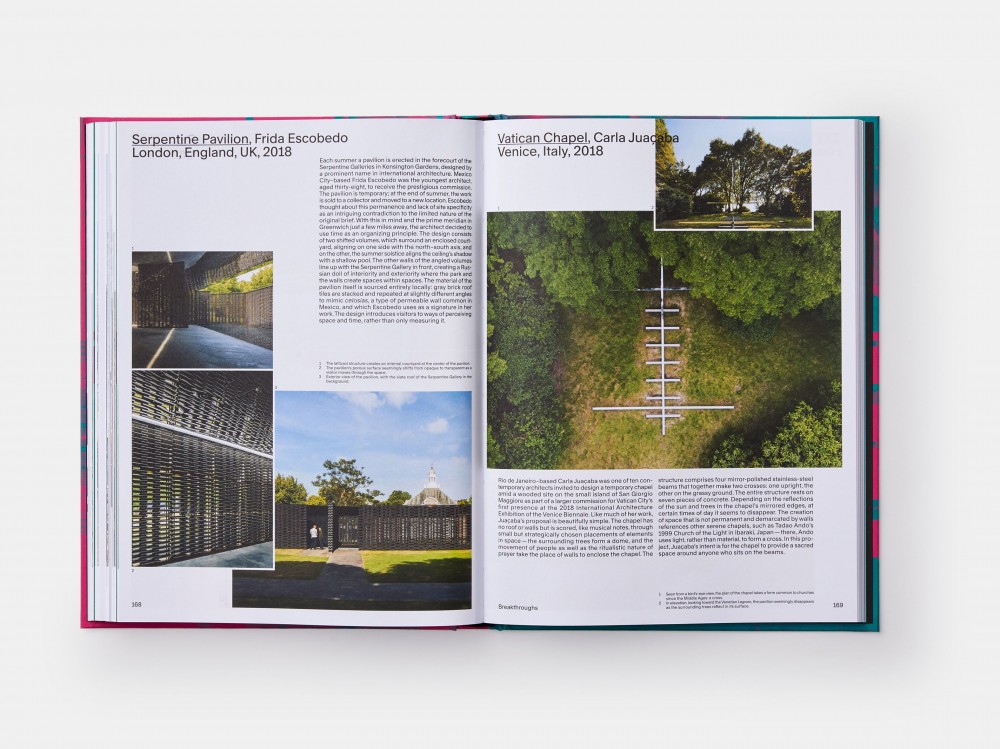

Pages 168 and 169 feature Frida Escobedo’s 2018 design for the Serpentine Pavilion in London, England. © Rafael Gamo (left) and Federico Cairoli (right).

-

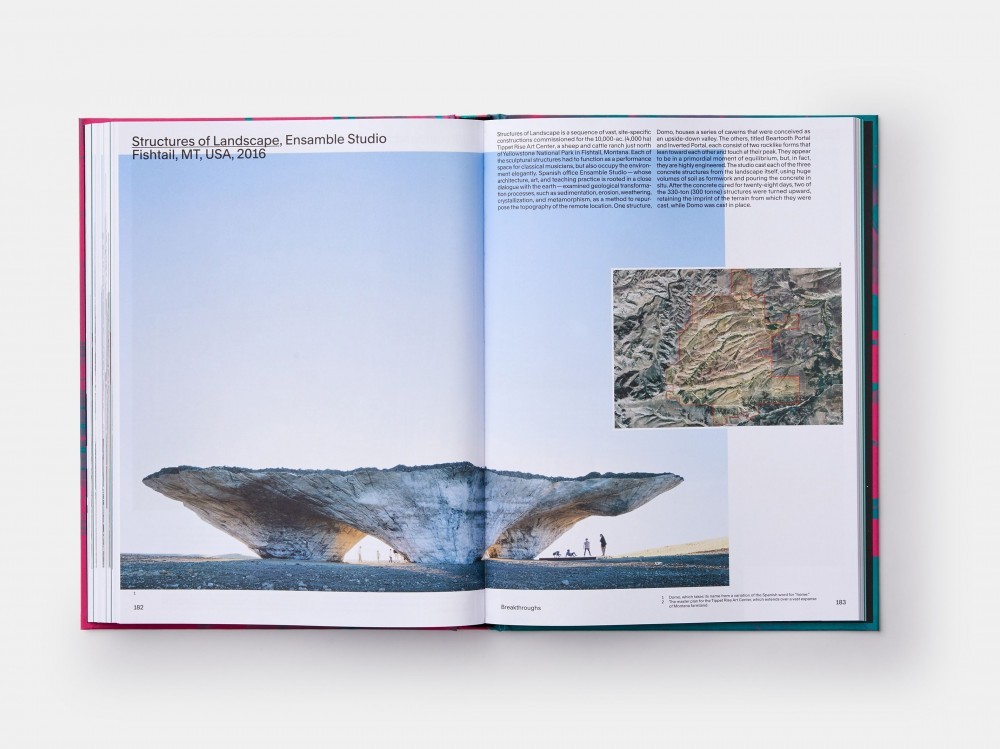

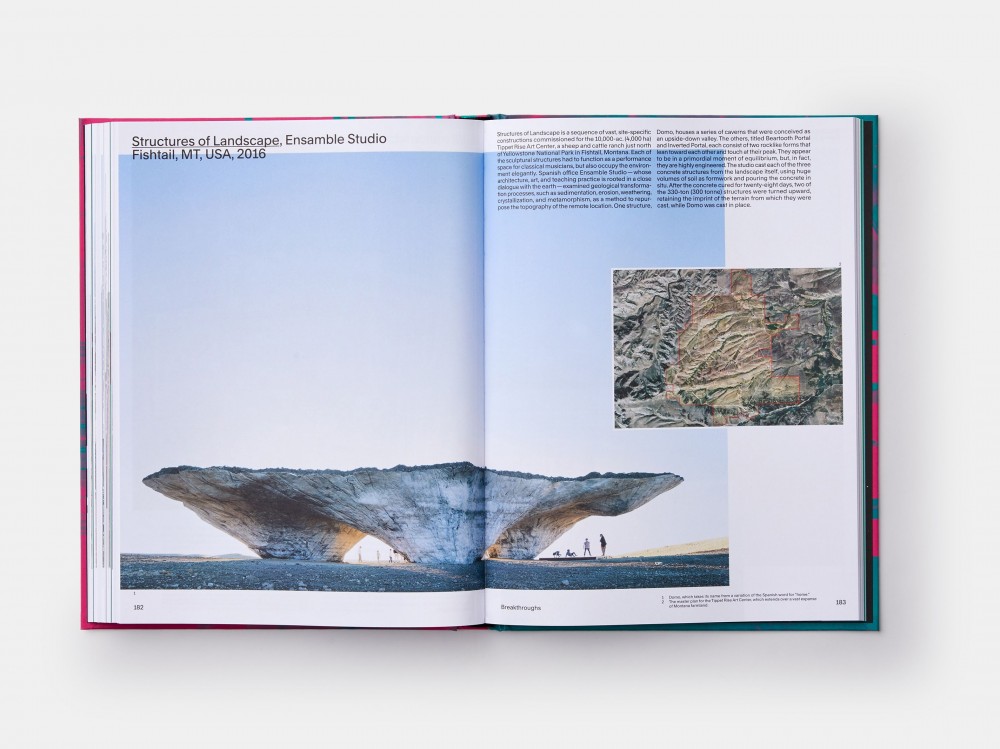

Pages 182 and 183 feature Structures of Landscape a large-scale intervention by the Ensamble studio at the Tippet Rise Art Centre in Fishtail, Montana. © Iwan Baan.

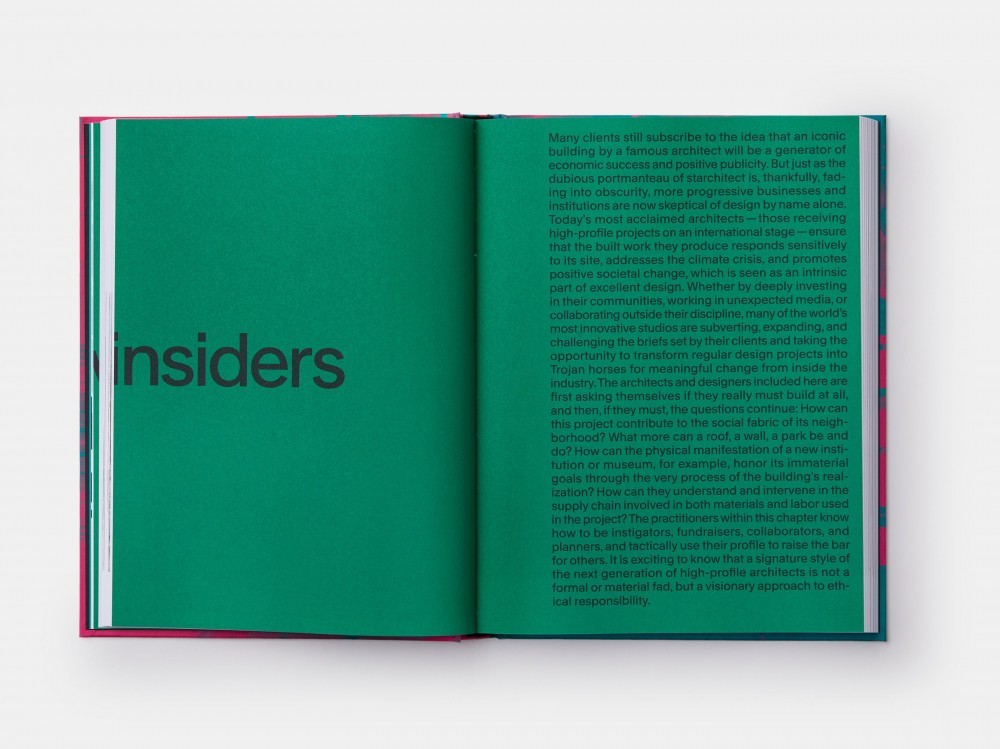

The chapter devoted to “insiders” features Amateur Architecture, a Chinese firm focused on projects in the rural countryside composed of husband-and-wife pair Lu Wenyu and Pritzker Prize-winner Wang Shu. Galilee highlights the Fuyang Cultural Complex which the duo completed in 2017, a commission they accepted on the condition they could also work on the restoration of the adjacent village of Wencun. Their rural intervention paid tribute to the village’s history using construction methods and materials indigenous to the region like rammed earth and reused stone. In stark contrast, the chapter also features Bjarke Ingels’s CopenHil (2019), an experiment in “hedonistic sustainability” in the form of a facility that functions as both a ski slope and a waste-to-energy power plant. The project hopes to help Copenhagen become carbon neutral by 2025. The chapter also revisits New York City-based firm Diller Scofidio + Renfro’s High Line project — the former railway transformed into a public park in 2009. Galilee, whose interest in the intersection of architecture and performance is one of the book’s defining features, recounts how nearly a decade after the park’s completion, the architects initiated an immersive performance, The Mile-Long Opera (2018), which brought together a thousand singers for a libretto narrating a story based on real New Yorkers’ day-to-day lives.

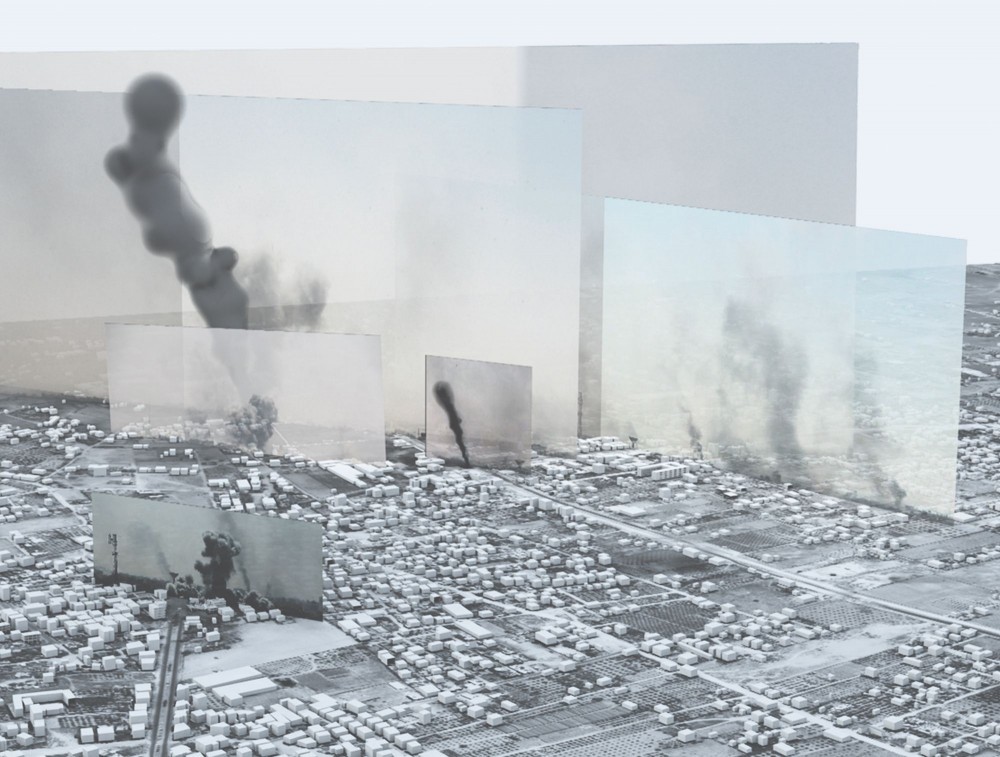

Contemporary artists make up most of the examples featured in the “radicals” chapter, which showcases work that is both provocative and aimed at generating change while being relatively free from commercial constraints. In London, Iraqi-American artist Michael Rakowitz replicated an Assyrian sculpture made from tins of date syrup bringing attention to the decimation of date palms as one of the Iraq War’s many casualties. In Texas, Belgian artist Mishka Henner’s Feedlots series (2012–13) reveals the disastrous nature of the food industry by combining hundreds of screen grabs from satellite-imaging software, showing speckled cattle pens next to lagoons of manure-turned-toxic-waste. Artist and filmmaker Arthur Jafa’s video piece Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death (2016) poignantly collages together found footage to create a nuanced portrait of Black life in America while photographer LaToya Ruby Frazier portrays the water crisis as suffered by her own community in the series Flint Is Family (2016).

Radical Architecture of the Future by Beatrice Galilee (Phaidon, 2020).

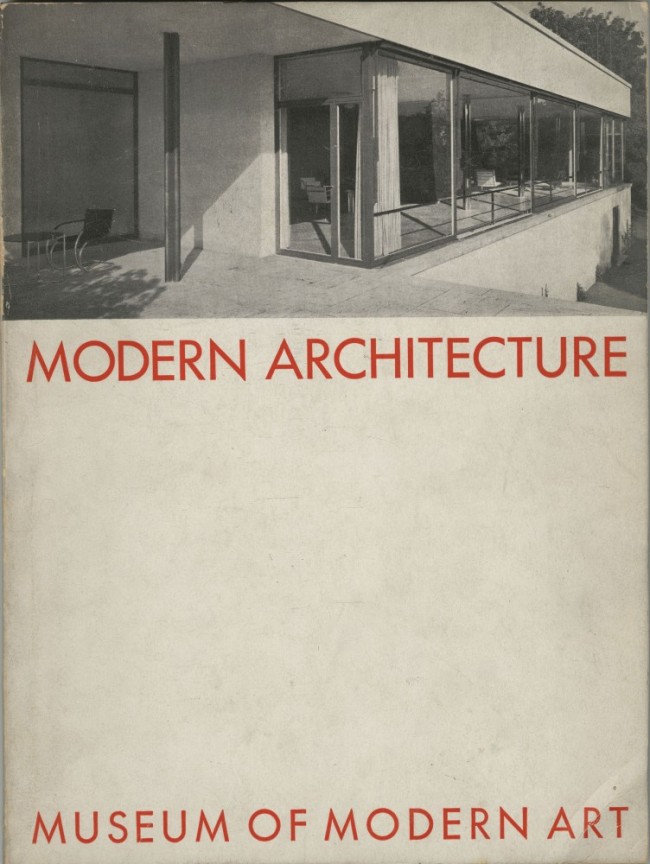

The chapter on “breakthroughs’’ features projects that use vernacular materials and construction techniques to create spaces for local cultural advancement, like a mosque and library in Niger by Atelier Masomi and Studio Chahar, and multiple projects in rural China by Xu Tiantian. Galilee also spotlights adaptive reuse projects like the London-based collective Assemble’s ongoing restoration of abandoned Victorian houses as well as artist Theaster Gates’s revitalization of old buildings in Chicago, like the Stony Island Arts Bank, through his Rebuild Foundation, aimed at creating spaces for Black people to thrive. This chapter also includes architecture historian Beatriz Colomina’s study of the relationship between the beginning of Modern architecture and the advent of X-ray technology.

Galilee argues that Bernard Rudofsky’s 1964 book and exhibition Architecture without Architects is just as relevant today as it was when he released it as unfortunately today we still rely on European Classicism and colonialism as the definitive canon of beauty — especially for institutional buildings which are meant to represent the people. Through this book, however, Galilee offers a counterbalance to these long-held biases, gathering together an inclusive collection of provocative thinkers and projects. Galilee offers a vision for how architects can forge a new future, accounting for social justice, sustainability, desegregation, and a world inclusive of disabilities, minorities, and biodiversity in their designs through a holistic approach. She asserts that today “these topics and issues are supercharged; they are interconnected, electrified, and global.”

Text by Natalia Torija Nieto.

Images courtesy of Phaidon.

Radical Architecture of the Future by Beatrice Galilee (Phaidon, 2020).